Most ancient Near Eastern demons have fallen into obscurity—mighty creatures like Humbaba, for instance, no longer provoke the fearful response they did in Mesopotamia during the early first millennium B.C. In fact, visitors to our galleries of ancient Near Eastern art tend to find Humbaba friendly and unassuming, a far cry from the terrifying adversary in the Epic of Gilgamesh who guards the Cedar Forest.

Left: Bronze statuette of the demon Pazuzu. Mesopotamia. 8th–7th century B.C. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités Orientales (MNB 467); Right: Roberto Cuoghi. Šuillakku, 2008. Frontispiece from Gioni, Massimiliano and Margot Norton, eds. Roberto Cuoghi: Šuillakku Corral. New York: New Museum, 2014

The exception seems to be Pazuzu, who is described in ancient texts as "the son of Hanbu and king of the wind demons." He stands on two legs and has human arms ending in claws, with two pairs of wings, a scorpion's tail, a snake-headed, erect penis, and a horned, bearded head with bulging eyes and snarling canine mouth. Amulets with images of his full body or, more often, just his head, were common in the early first millennium B.C. Although not everyone will recognize the name "Pazuzu," his monstrous form appears in many unexpected places. A giant version by the contemporary artist Roberto Cuoghi comes to mind.

Cuoghi's monumental rendering of Pazuzu is based on an iconic, 15-centimeter high sculpture from the Louvre Museum, which is included in the exhibition. Although only small images and amulets have been found from the ancient world, Cuoghi's Pazuzu looks entirely appropriate. Like the cylinder seals that are so characteristic of ancient Near Eastern art—and that also look perfectly at home when enlarged—the Pazuzu statuette is a monumental work of art on a small scale.

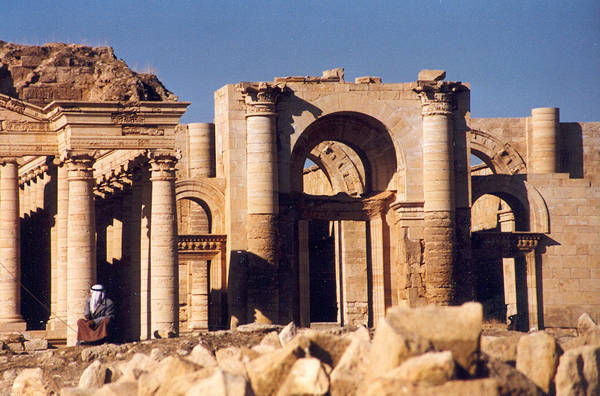

Hatra ruins by User:Victrav Own work. Via Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps the most famous modern Pazuzu is the demon who possesses a twelve-year-old girl in the 1973 horror classic The Exorcist. Of the two priests charged with exorcising the demon, one has encountered the same malevolent spirit before, while participating in an archaeological dig.

Scene from the 1973 film The Exorcist

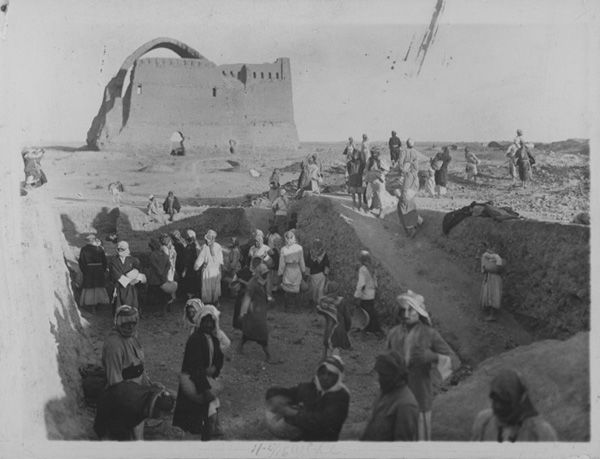

The movie sets up this back story by opening on an excavation in progress: the screen identifies the setting as simply "Northern Iraq." It is the site of Hatra, instantly recognizable from the columned facades of its great iwans (barrel-vaulted halls). The film was shot on location, with Iraqi extras playing workmen at the dig site—although the dozens of workmen swinging picks and rushing to and fro with wheelbarrows are more reminiscent of nineteenth- or early twentieth-century excavations than they are of modern, much more careful (and less kinetic) digs.

Workmen clearing a trench behind the Taq-i Kisra, Ctesiphon, Iraq. Joint Expedition of the Staatliche Museen, Berlin, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1931–32

Hatra, a magnificent city that was home to at least a dozen temples and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, certainly makes an impressive backdrop. The camera passes over Corinthian capitals and the carved head of an eagle, which evoke Greco-Roman architecture and sculpture—a more reliable indication of great antiquity for an American viewing audience, perhaps, than the mud-brick stumps of walls at most Mesopotamian sites.

Limestone Door Lintel with Lion-Griffins. Hatra, Main Palace, North Hall doorway. Parthian period, ca. 2nd–early 3rd century A.D. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1932 (32.145a, b)

The grand buildings on the screen were built by the Parthians, nomadic peoples originally from Iran who ruled the Near East from the second century B.C. to the second century A.D. The Classical design elements in Parthian architecture reflect a Near Eastern world that had been conquered by the Macedonian armies of Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C., spreading Greek influences and disrupting the unbroken chain of ruling dynasties connected to the deep cultural history of Mesopotamia. By the time of the Parthians, Pazuzu's image was already almost out of use; only two representations of the demon can be dated to this period.

Scene from the 1973 film The Exorcist

An early scene from The Exorcist shows a human-size Pazuzu statue on view at the site, and there is an uneasy expression on the face of the archaeologist-priest as he gazes at it. Had it existed, the statue would have probably seemed archaic to the Parthians, a survival from an earlier period whose identity and meaning may even have been forgotten, as they are in the movie itself. The camera lingers on the back-lit statue, as the noise of a nearby pack of dogs fighting provides an atmospheric soundtrack for the demon statue's canine snarl. The scene has been set: Pazuzu appears as a foreign, ancient, violently malevolent source of evil power. But what basis, if any, does this have in what we actually know about him?

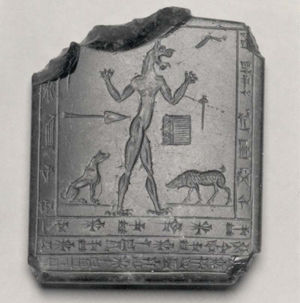

Left: Bronze Pendant of the Head of Pazuzu. Mesopotamia. Neo-Assyrian period, ca. 8th–7th century B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Norbert Schimmel and Robert Haber Gifts, and funds from various donors, 1993 (1993.181); Right: Stone plaque with image of Pazuzu. Mesopotamia. 8th–6th century B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Lent by Nanette B. Kelekian (L.2004.8)

Pazuzu was most popular in the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, from about the late eighth century B.C. through the sixth century B.C. In fact, two Pazuzu images dated to this era are included in the exhibition: the statuette that inspired Cuoghi, and a macehead with four back-to-back Pazuzu faces that had been dedicated at a Greek sanctuary on the island of Samos. A gold fibula (garment pin) decorated with his grimacing head, buried in a royal woman's grave at Nimrud, is the earliest archaeologically dated image of Pazuzu. Other fibulae in bronze, as well as small amulets meant to be worn on the body—perhaps strung on a necklace or around the wrist—show that his head was kept close at hand, in spite of its frightening appearance. This is unexpected and intriguing. Why would anyone want an intimate relationship with such a hideous image?

To answer this question, we must examine the relationship between supernatural creatures and humans in the ancient Near East. Although they are often classified as either evil or protective in modern scholarship, supernatural beings in ancient references seem to be presented as largely amoral. Their harmful or beneficial effects could be manipulated: they could be appeased with offerings and incantations, and even directed against each other by a skilled practitioner of magic. Pazuzu, as a powerful demon, was frequently set up as a shield against another supernatural terror: Lamashtu, a female demon with broad and far-ranging destructive powers, especially feared by pregnant women and those with newborns, who were her favored (but not only) victims.

Amulet with a Lamashtu Demon, ca. early 1st millennium B.C. Mesopotamia or Iran. Obsidian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, James N. Spear Gift, 1984 (1984.348)

Rather than a demon who viciously possessed defenseless humans, as in The Exorcist, Pazuzu was actually a powerful defense against demonic attacks from Lamashtu. In the movie's world, his frightening appearance was enough to make him a plausible enemy, but in his original context, Pazuzu's identity was far more complicated, and more interesting, than as one side in a simple opposition between good and evil.