It’s early spring. The brilliant white cherry blossoms are reaching their peak.

Nearby, green buds unfurl on the sprigs of a young willow tree.

In Japan, there is a long and storied tradition of enjoying—and representing—the flora of each season, especially spring and autumn.

Here, the artist Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828) captures the shining beauty of spring on a gilded folding screen. Paintings like this introduced new ways of appreciating and describing the natural world.

But this pleasant scene is more than just an expression of nature’s charm. Possessing such artworks was also a way for members of high society to position themselves as the heirs of a noble past.

Hōitsu painted Cherry and Maple Trees in the early 1820s, near the end of Japan’s long Edo period (1615–1868), an era of relative peace and prosperity.

Starting in the late 16th century, the court nobility, samurai elite, and newly ascendant merchant class had fallen under the enchantment of nostalgia for an idealized past.

They restored certain traditions and values from the Heian period (794–1185)—which they looked to as a golden age of peace and refinement—and laid claim to their attendant status.

Throughout the Edo period, advancements in publishing meant classic literary tales became available in affordable editions. Woodblock prints proliferated, especially ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”). Samurai weapons and armor became more decorative or ceremonial than functional.

Arts, literature, philosophy, and science—especially study of the natural world—all flourished, despite the strict social and political control exercised by the Tokugawa shoguns, military leaders based in Edo (present-day Tokyo).

One remarkable innovation was the development of the Rinpa aesthetic.

Characterized by bold natural motifs, references to traditional court literature and poetry, the use of lavish pigments, and experimentation with brush techniques, Rinpa extended to textiles, ceramics, lacquerware, and other media.

Wealthy patrons used Rinpa screens like this one to establish intimate spaces within larger reception rooms. They rotated with the seasons and set the mood for tea ceremonies and other leisurely pursuits.

Screens created an immersive, almost theatrical atmosphere for composing and reciting poems—such as haikai, the 17-syllable precursor to the famous haiku.

Rinpa screens are poetic interpretations of a landscape. While their compositions are botanically accurate—we can identify each plant, such as the yellow dandelions and the gently curved fiddlehead ferns—they’re also stylized, decorative, and slightly abstract.

Rinpa is named after the renowned Kyoto painter Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716). The word translates to “school of Rin” and derives from the final syllable of the painter’s name.

Today, Hōitsu is known for helping to revive the Rinpa School (as it came to be known in modern times) in Edo.

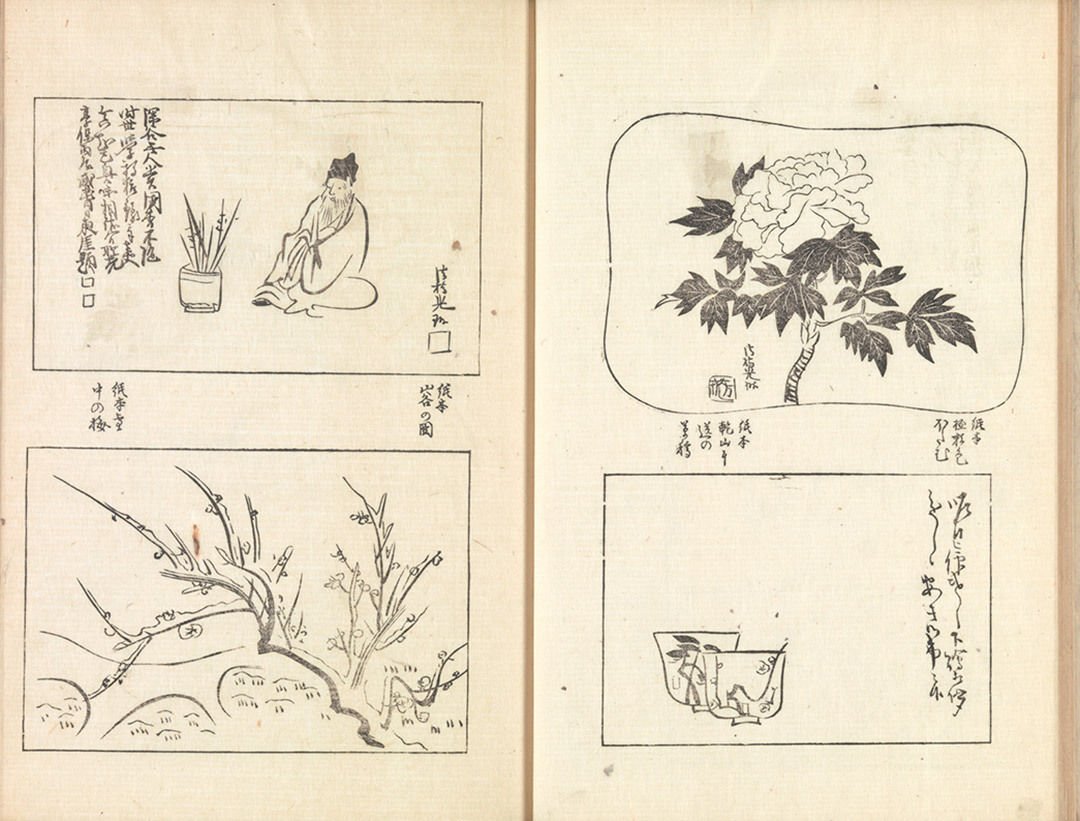

Hōitsu’s family—samurai nobility—was well connected, and the artist had access to original works by Kōrin. Hōitsu even created a woodblock-printed compendium of paintings he’d seen, called One Hundred Paintings by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu).

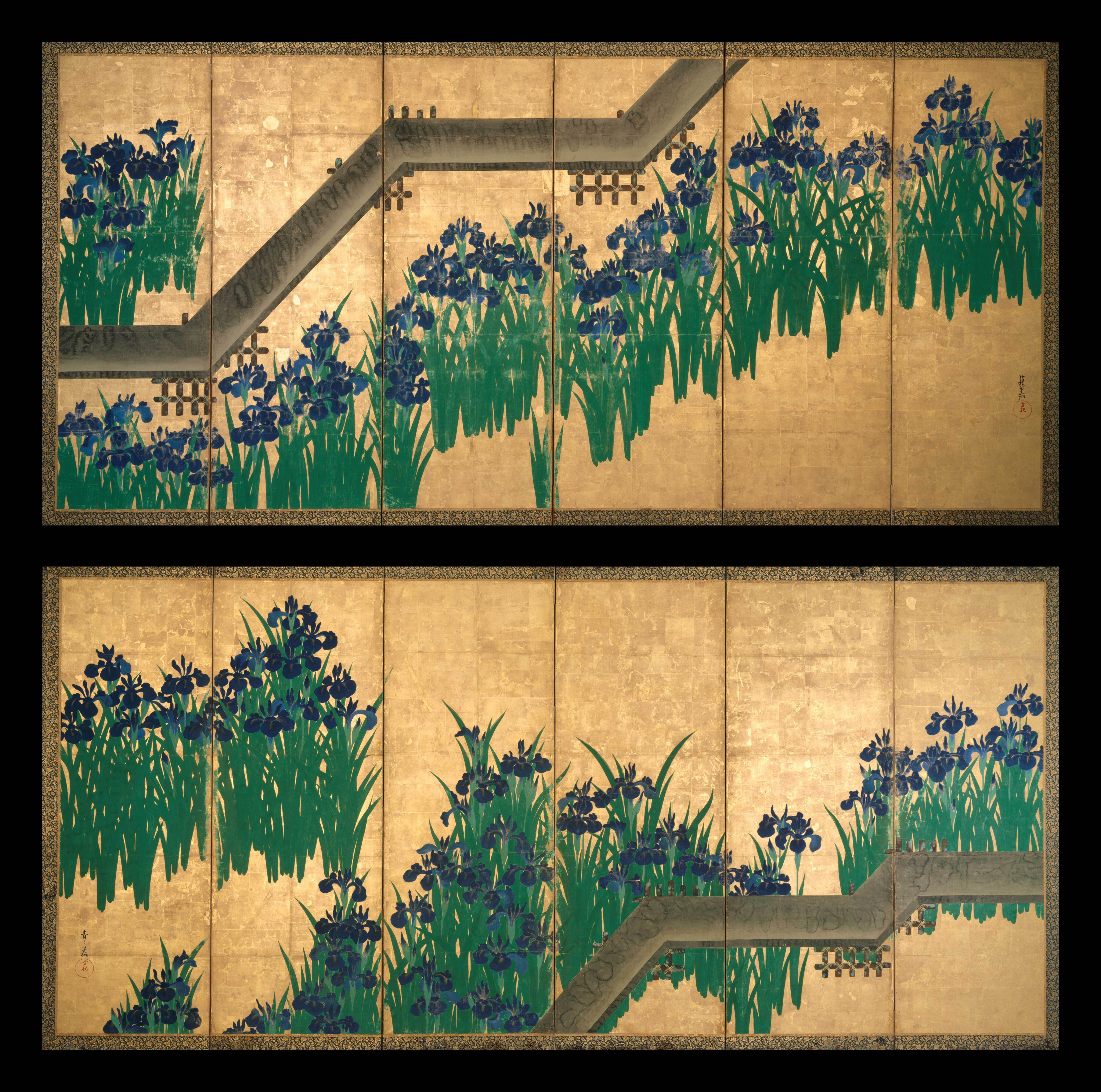

Kōrin’s Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges), made around 1710, is recognized as one of the artist’s masterpieces—and a key work in defining the Rinpa painting aesthetic.

Tall, regal irises emerge from an abstracted marsh along an angular bridge that sweeps diagonally across a pair of screens. They seem to float against unbroken panes of gold leaf.

This scene references an episode from the literary classic The Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari). Exiled from Kyoto after a love affair goes awry, the unnamed protagonist rests near a marsh with irises in bloom and composes a nostalgic love poem for his estranged wife.

The first syllable of each line forms the Japanese word for “irises”: kakitsubata.

Karagoromo

kitsutsu narenishi

tsuma shi areba

harubaru kinuru

tabi o shi zo omou

In the English translation, the first letters of each line also spell out the flower’s name:

I wear robes with well-worn hems,

Reminding me of my dear wife

I fondly think of always,

So as my sojourn stretches on

Ever farther from home,

Sadness fills my thoughts.

Notice how Kōrin doesn’t depict the tale’s narrator or his retinue of courtiers. Instead, the artist presents the captivating flowery marsh that inspired the poet. Viewers in the Edo period would have immediately understood Kōrin’s literary reference.

Rinpa artists brought literary and historical concepts into the present, renewing their political and social relevance.

Part of what makes Kōrin’s work so powerful is its use of rusu moyō, a Rinpa device meaning “the motif of absence.” It’s this very lack of human figures that allows you to project yourself into the scene.

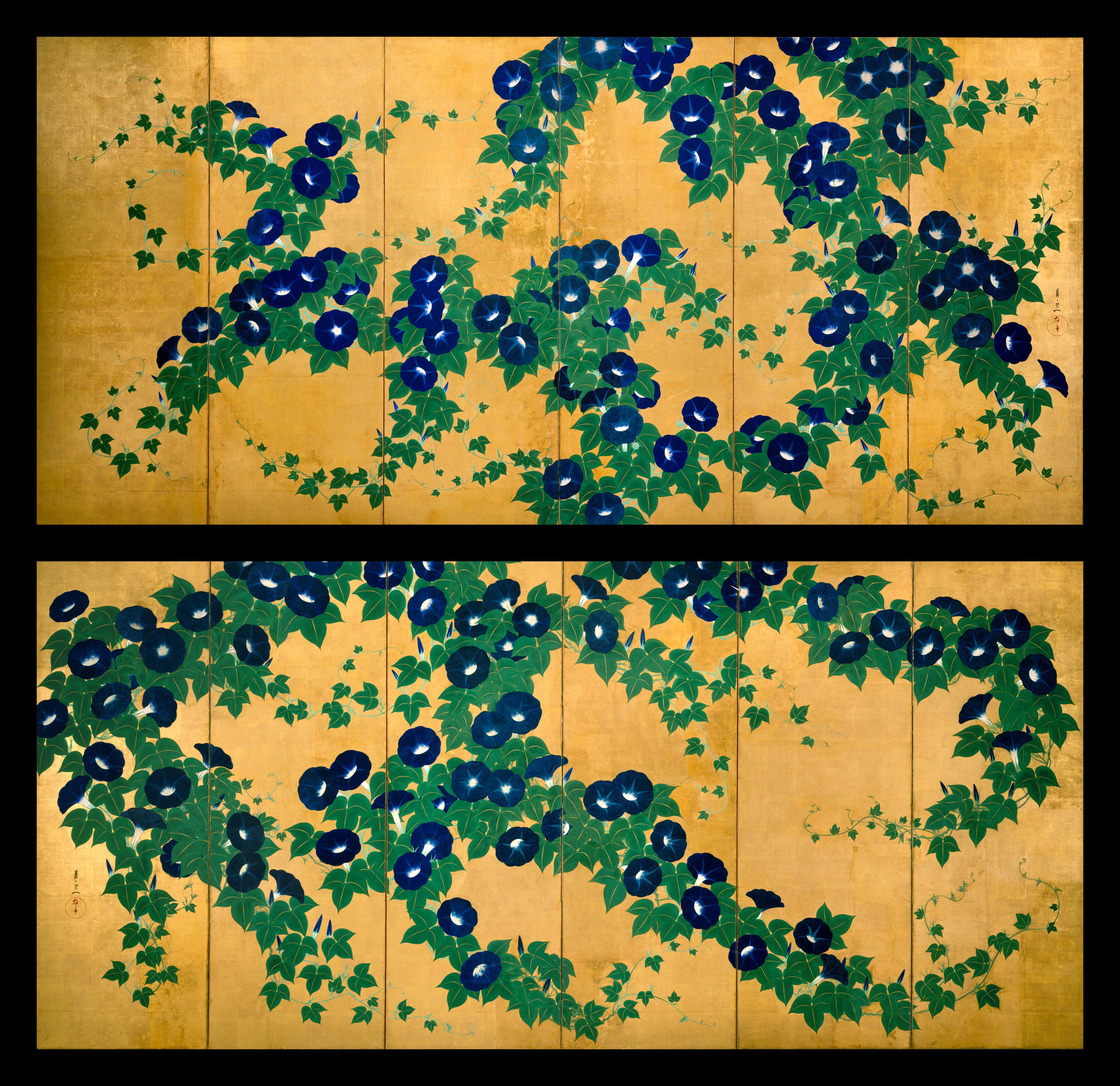

Suzuki Kiitsu’s Morning Glories is another extraordinary example of rusu moyō painted 140 years later. The motif remained a through line across centuries of Rinpa painting.

Rinpa screens are meant to be read from right to left. The vines seem to reach toward each other across the two screens.

The morning glories are painted in a range of vibrant colors. Some are a deep indigo blue; others have a brighter hue.

These screens present a lush atmosphere of flowers.

But notice the gaps among the vines. Even though no one is depicted in this screen, there are signs of human presence. The way the morning glories fall suggests a trellis in a courtly garden.

The Rinpa School spanned nearly the entire Edo period, which ended in 1868 when the Meiji Restoration re-established imperial rule in Japan.

The Met’s three sets of masterpieces by Kōrin, Hōitsu, and Kiitsu gloriously encapsulate a century and a half of intergenerational artistic influence.

Hōitsu’s screens brilliantly embody this cultural transmission. He built on Kōrin’s literary themes and presented a wider range of seasonal imagery.

Hōitsu later mentored Kiitsu, who became a master of the Rinpa School in his own right.

This intergenerational exchange, however, didn’t just flow from mentor to student. By the 1820s, it appears Hōitsu had adopted the stylized patterns of his protégé Kiitsu, who originally trained as a textile dyer.

Observe the precision and definition of the leaves and blossoms in Hōitsu’s screen. The flowers, like Kiitsu’s blue morning glories, are highly stylized. Many look as if they may have been stenciled.

Beneath the boughs are springtime flora, such as fiddlehead ferns, dandelions, sorrels, field-horsetail shoots, violets, and Japanese primroses.

Cherry blossoms have long featured in a 31-syllable form of classical poetry called waka. But the flowers beneath the trees didn’t regularly appear in Japanese verse until the early modern period, when poets trained their eyes on these more humble flora.

Hōitsu rendered the tree trunks through an impressionistic ink-mottling technique called tarashikomi. Meaning “dripping in,” tarashikomi involves adding ink directly to a wet painting surface.

Notice how he used shades of brown to suggest soft light and texture on the trunks.

And see here, where the artist dropped in dots of luminescent oyster-shell pigment (gofun) on top of the areas made by tarashikomi to resemble the appearance and texture of lichen.

The use of tarashikomi is unpredictable on gold leaf, but Hōitsu mastered the technique, as you can appreciate in the controlled application.

Accompanying this springtime scene is a second six-paneled image.

It depicts two maple trees at the peak of their crimson glory.

Growing in the trees’ shade are ground-cover bamboo, chrysanthemums, and Japanese gentian—plants that bloom in autumn.

As you can see, there’s something fantastical about Hōitsu’s depictions of flora.

The angle of the maple trees echoes the leaning cherry blossoms in the other panel, creating a sense of visual and seasonal rhythm.

This set of screens depicts a landscape that would be impossible to witness in real life. Together they convey the recurring cycle of the seasons—and suggest that our lives must remain in tune with nature.

In this way, Rinpa screens are a dazzling testament to nature’s charm.

But through their literary and poetic references, they also reveal a conservative feudal society’s quest for courtly sophistication and refined cultural pastimes.

These gorgeous screens illustrate how artists have always rediscovered and updated traditions. Like windows onto the past, they shed light on the cultural and social contexts of their creation.

They encouraged viewers of their time to insert themselves into idealized natural settings imbued with nostalgia, literary allusion, and a general sense of well-being.

When we look at them today, they can similarly remind us of our own place in the world and prompt us to reflect on what aspects of our time we hope to preserve for the future.

* * *

Sakai Hōitsu’s Cherry and Maple Trees is on display in the exhibition Japan: A History of Style through August 7, 2021.

Ogata Kōrin’s Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges) and Suzuki Kiitsu’s Morning Glories are currently not on view.

Sakai Hōitsu (Japanese, 1761–1828). Cherry and Maple Trees, early 1820s. Japan, Edo period (1615–1868). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold leaf on paper; each screen: 65 × 134 ½ in. (175.3 × 341.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mary and James G. Wallach Foundation Gift, Rogers and Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation Funds, and Brooke Russell Astor Bequest, 2018 (2018.55.1, .2)

Sakai Hōitsu (Japanese, 1761–1828) after Ogata Kōrin (Japanese, 1658–1716). One Hundred Paintings by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu), 1815 (first two volumes) and 1826 (two sequel volumes). Four volumes of woodblock printed books; ink on paper, each 10 ⅜ × 7 ½ × 1 in. (26.4 × 18.3 × 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Howard Mansfield Collection, Gift of Howard Mansfield, 1936 (JIB118a–d)

Ogata Kōrin (Japanese, 1658–1716). Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges), after 1709. Japan, Edo period (1615–1868). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink and color on gold leaf on paper; each screen: 64 ½ × 138 ¾ in. (163.7 × 352.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Louisa Eldridge McBurney Gift, 1953 (53.7.1, .2)

Suzuki Kiitsu (Japanese, 1796–1858). Morning Glories, circa 1850. Japan, Edo period (1615–1868). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold leaf on paper; each screen: 70 ¼ × 149 ½ in. (178.4 × 379.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Seymour Fund, 1954 (54.69.1, .2)