When the US Navy forcibly removed Paul Cadmus’s 1934 painting The Fleet’s In! from an exhibition at The Corcoran Gallery of Art before it opened that same year, a national scandal unfolded. Reproductions of the work proliferated in newspapers across the country, catapulting Cadmus into the media spotlight. The unmentioned queer presence in his painting ignited one of the earliest known cases of censorship of a gay artist in the United States.

Cadmus—a classically trained artist whose teacher Charles Hinton was a student of the French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme—spent two years in Europe with his lover and fellow artist Jared French. In 1933 Cadmus returned to the United States to participate in the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), a New Deal program that provided artists with a weekly income to paint US scenes of their choice. Cadmus chose a group of inebriated sailors and one marine socializing with civilians in Manhattan’s Riverside Park during shore leave. It was slated for inclusion in a group show at The Corcoran in Washington, D.C.

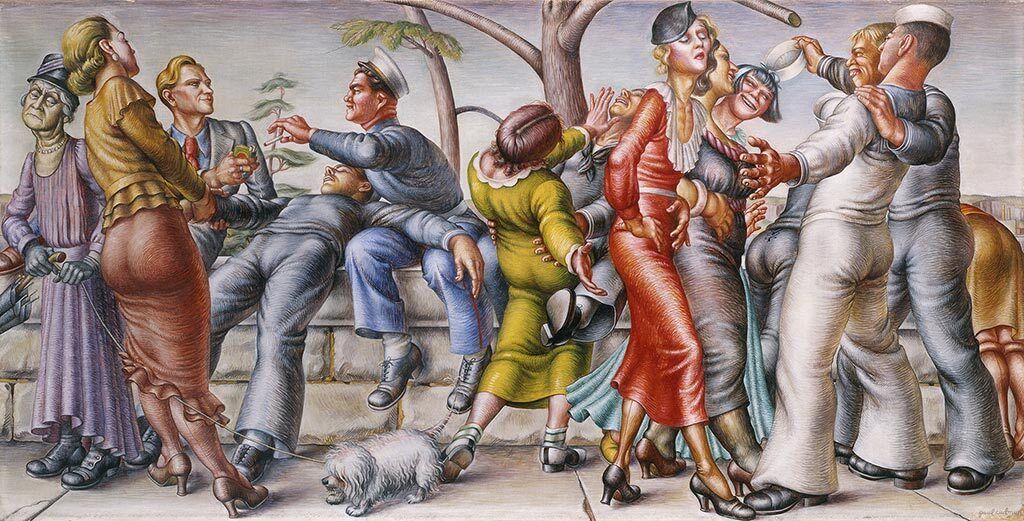

Paul Cadmus (American, 1904–1999). The Fleet’s In!, 1934. Tempera on canvas, 37 × 67 in. (94 × 170.2 cm). Courtesy of Navy Art Collection, Naval History and Heritage Command. Image © 2021 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

After spotting a reproduction of The Fleet’s In! in a preview of the exhibition, retired Navy General Admiral Hugh Rodman published a letter in multiple newspapers. “It represents a most disgraceful, sordid, disreputable, drunken brawl,” he wrote. “Apparently a number of enlisted men are consorting with a party of streetwalkers and denizens of the red-light district.” While highly pejorative, Rodman’s description is literally correct.

In April 1934 Rodman ordered Henry Latrobe Roosevelt, then–Assistant Secretary of the Navy, to remove the painting from the show before it opened and ensure that it would never be displayed publicly again. Roosevelt went into the gallery, lifted the painting from the wall, and according to the source, either took it home or hung it in the Navy secretary’s bathroom. After his death in 1936 he “bequeathed” it to the Alibi Club, an exclusive men’s lounge for high-ranking government officials, where it hung for four decades until the Naval History and Heritage Command was given custody. It remains in their collection today.

Page B-1 of the April 3, 1934, issue of the Washington Evening Star, which included an image of Cadmus’s The Fleet’s In! (detail at right). Image courtesy the Library of Congress

“It represents a most disgraceful, sordid, disreputable, drunken brawl. Apparently a number of enlisted men are consorting with a party of streetwalkers and denizens of the red-light district.”

— Retired Navy General Admiral Hugh Rodman

The painting’s theft from the Corcoran was just the beginning of the scandal, however. Multiple publications wrote about Cadmus’s incident with the Navy. Making the most of his notoriety, the artist pointed out to the New York Times, “I don’t think admirals have much sense of humor, if they are as deeply offended as reported. By attacking my painting, naval officials have only called attention to it, whereas if they had said nothing about it, it probably would have been noticed only by the art critics.”

Cadmus provided countless local and national newspapers across the country with direct quotes, actively shaping the narrative around his censorship. He even had the painting photographed and personally distributed the images to the press. “I owe the start of my career really to the Admiral who tried to suppress it,” Cadmus later said. [1]

A queer presence and coded encounters

How did one image cause so much contention? The Navy publicly decried Cadmus’s portrayal of drunk enlisted men soliciting prostitutes on their shore leave, but one figure may have especially riled the admiral.

Paul Cadmus (American, 1904–1999). The Fleet’s In! (detail), 1934. Tempera on canvas, 37 × 67 in. (94 × 170.2 cm). Navy Art Collection, Naval History and Heritage Command. Image © 2021 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The scholar Richard Meyer wrote in Outlaw Representation (2002) that the blond-haired civilian in Cadmus’s painting fits the characteristics of the gay male “fairy” or “pansy” archetype from the 1930s—a gay man with feminine characteristics and specific queer signifiers. In Cadmus’s painting, the effeminate blond marks a contrast with the masculine servicemen, who wouldn’t have been considered homosexual in the 1930s even if they held same-sex desires.

The blond’s red tie was a well-known queer visual code that conveyed his availability. George Chauncey wrote in Gay New York (1994) that other indications include his “plucked eyebrows, rouged lips, powdered face, and marcelled, blonde hair.” The blond makes a pass at the marine, who accepts his offered cigarette with an eager expression.

The painting’s queerness extends beyond the pansy figure. At the far right, two of the sailors have their arms around each other. Their tight uniforms emphasize their genitals and buttocks, which appear in suggestively close proximity. Tight clothing recurs throughout the painting, which Cadmus skillfully uses to sexualize his figures and their desire.

Paul Cadmus (American, 1904–1999). The Fleet’s In! (details), 1934. Tempera on canvas, 37 × 67 in. (94 × 170.2 cm). Courtesy of Navy Art Collection, Naval History and Heritage Command. Image © 2021 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

On the left, a woman tries to lift a sailor passed out on top of the wall. Her dress is tight, and so are the pants around the sailor’s crotch. Another sailor wraps his hands around a woman’s waist; she sticks her hand in his face, rejecting his advance while reaching her other hand to cup a woman’s bottom nearby.

While many of the figures express clear same-sex desire, sexual orientation is not presented as a binary. For example, the figure in the red dress is depicted with some gender ambiguity—their makeup is apparent but their sternum and breastbone appear somewhat masculine and they have an Adam’s apple. Prohibitionary laws made public transvestism rare in the 1930s outside of certain downtown neighborhoods, but the figure resembles a caricature of the era’s drag-ball crossdressers.

Cadmus places the enlisted men within a multifaceted exchange of sexual preferences—they express, and are objects of, diverse desires.

On the right end of the painting, the white-uniformed sailor’s hand extends over one woman’s breast and he looks directly into her eyes. This is the most overt depiction of heterosexual desire in the painting, and it parallels the gaze between the blond and the sailor. Cadmus places the enlisted men within a multifaceted exchange of sexual preferences—they express, and are objects of, diverse desires.

Documenting queer life in early 20th-century New York

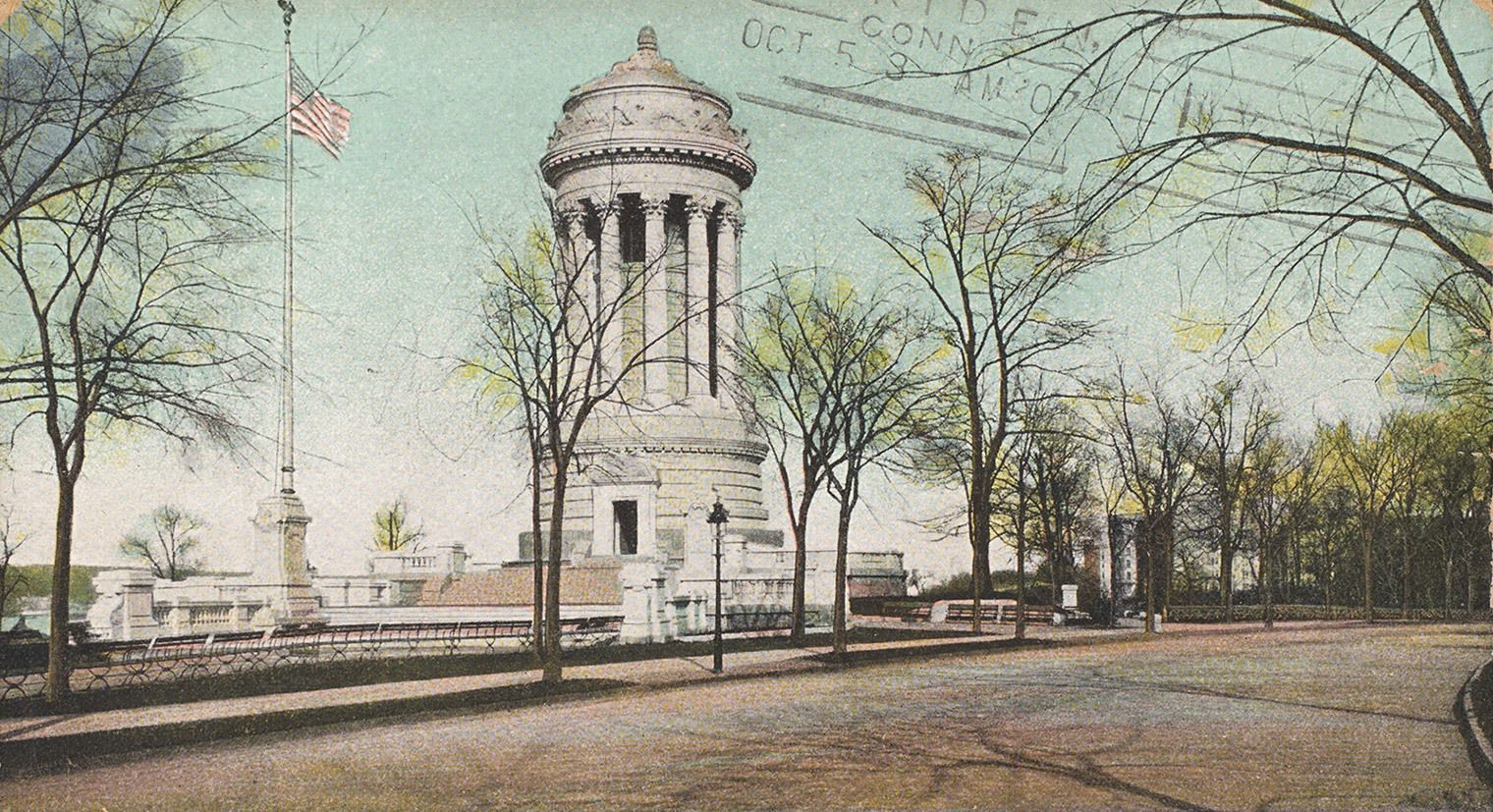

Cadmus’s complex image reflects an understanding of early twentieth-century queer history. It was a known fact that from World War I onward servicemen participated in homosexual encounters around New York City. The Brooklyn Navy Yard, Times Square, and various waterfronts such as Riverside Park and the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument (the likely setting of this painting) were well-known pick-up spots for gay men in the 1920s and ’30s. Accounts of sailors cruising for gay men and female prostitutes affirm Navy members’ participation in what Chauncey described as the “urban evils of city life.”

Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, New York, 1900s–1930s. Photomechanical print, 3 ½ × 5 ½ in. (9 × 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive, 1994 (1994.264.65.65).

Efforts to curb servicemen’s vices, such as engaging with prostitutes and consuming alcohol, were successful to a degree, but organizations that policed “immoral” behavior recorded an uptick of enlisted men participating in clandestine sex after the First World War. The accessibility of public parks made them essential entryways for men seeking companionship, and servicemen who cruised these spots were enmeshed in vital social circles for gay men.

Art historian Jonathan Weinberg notes in Speaking for Vice (1993) that the general public may not have picked up on the coded homosexual iconography or history of The Fleet’s In!. The Navy, however, would have been well aware. And Cadmus, who grew up on 103rd Street just off Amsterdam Avenue, witnessed the drunken scenes at the nearby waterfront park. “I always enjoyed watching them when I was young,” he later stated. “I somewhat envied them the freedom of their lives and their lack of inhibitions. And I observed. I was always watching them.”

How Cadmus employed printmaking to subvert censorship

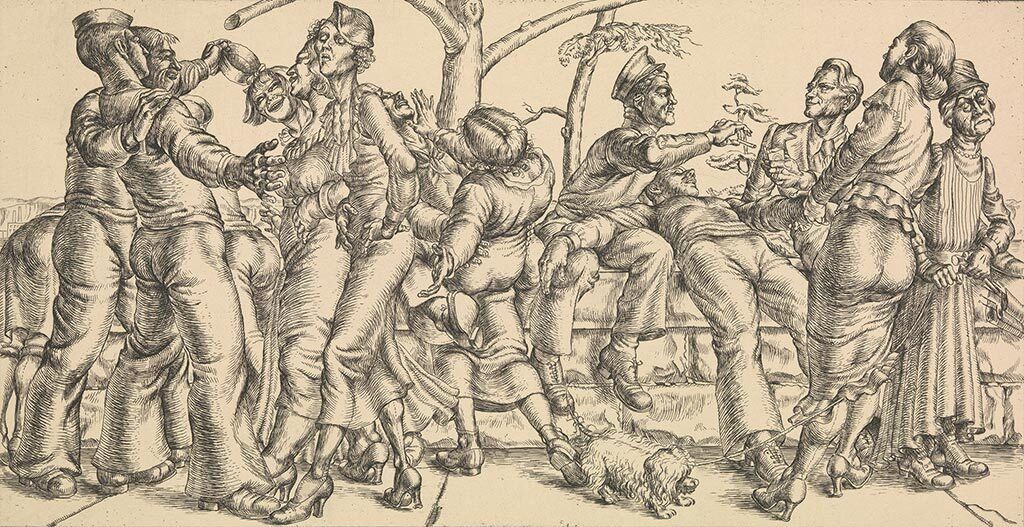

“I am going to do the picture as an etching,” Cadmus declared in one of the many indignant responses he gave to the media. “They can tear up the canvas, but they will have a sweet time eating copper.” [2] Later in 1934 the artist produced fifty prints of The Fleet’s In!. While the artist made other prints based on his finished paintings, such as Y.M.C.A. Locker Room (1934) and Coney Island (1935), these were in direct response to censorship, making their creation unique.

Paul Cadmus (American, 1904–1999). The Fleet's In!, 1934. Etching, 11 ½ × 15 ¾ in. (29.2 × 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of George Platt Lynes, 1940 (40.99.3). Image © 2021 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“They can tear up the canvas, but they will have a sweet time eating copper.”

— Paul Cadmus

Etchings were the dominant form of printmaking in the early twentieth-century fine art market, especially images depicting idealized figures, landscapes, and architecture studies that harkened to works by European Old Masters. [3] Cadmus belonged to a category of etchers who deviated from these traditional subjects to depict modern themes, such as urban satire. Cadmus’s prints of The Fleet’s In! may lose the painting’s rich color and sense of depth, and slightly obscure signifiers like the red tie, but they emphasize the image’s structure and frieze-like composition while perfectly maintaining its comic debauchery.

Cadmus made his first edition of etchings, which he sold for nine dollars each, at The Art Students League of New York; he preserved the copper plate and produced twenty-five subsequent prints in 1970. These prints made for public purchase reflect the realities of New York City in the 1930s, when artists like Cadmus struggled to sell their work during the Great Depression. In 1940 Cadmus’s friend George Platt Lynes gifted a print to The Met.

Cadmus’s legacy and the importance of displaying queer art

Although Cadmus was the subject of much art historical literature in the 1930s, the rise of Abstract Expressionism and the artist’s known homosexuality contributed to a steady decline in scholarship; Cadmus was part of a generation of American figurative artists who fell into relative obscurity. It wasn’t until the 1960s and ’70s that Cadmus received renewed attention when he was reclaimed by gay magazines such as Vector. (Even as the gay liberation movement elevated his work, Cadmus remained ambivalent about the label “gay art.”) Late twentieth-century and present-day scholarship and exhibitions have now welcomed Cadmus back into the discourse around sexuality and queer history. Since the 1930s, The Met has regularly acquired a number of Cadmus’s drawings, prints, and paintings, including Gilding the Acrobats (1935) and his series “The Seven Deadly Sins.”

In the 1980s, art historians successfully advocated for the inclusion of The Fleet’s In! within a retrospective of Cadmus’s work—the first time it was on public display since 1934—which led to its acquisition by The Naval Historical Society. Today, counter to its early censorship, the painting is displayed as part of the Navy’s collection and frequently loaned to other museums. The Met recently exhibited The Fleet’s In! at the 2019 exhibition Camp: Notes on Fashion, where it was placed alongside Jean Paul Gaultier’s disco sailor suit riffing on the trope of gay or sexualized sailors established by artists like Cadmus, Charles Demuth, and Tom of Finland.

Installation view of Camp: Notes on Fashion

Cadmus’s current reception reflects shifting attitudes toward homosexuality but there are still many critical considerations surround the painting. The US government violated Cadmus’s freedom of expression and censored a work that was funded by and meant for the public. The Met’s print serves as a record of the painting’s censorship as well as the suppression of queer perspectives throughout US history. Had the painting never been given to The Naval Historical Society, Cadmus’s prints and photographs might have been the only public evidence of The Fleet’s In!.

Through exhibition, advocacy, and research, scholars ensure that the artistic contributions of the LGBTQIA+ community are not forgotten. When works of art circulate as part of the public dialogue, history can be celebrated and, when necessary, reevaluated. For many years Paul Cadmus existed on the periphery of mainstream cultural interests, but the recent exposure of his work heightens our appreciation for the complex and vibrant ways that queer culture has manifested throughout history.

Notes

[1] David Leddick, Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 48. return

[2] Philip Eliasoph, Yesterday and Today (Miami: Miami University Art Museum, 1981), 117. return

[3] Helen Langa, Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004), 13. return

Marquee: George Platt Lynes (American, 1907–1955). [Paul Cadmus, Stage Set Stairs] (detail), ca. 1937. Gelatin silver print, 4 ¾ × 3 ¾ in. (11.9 × 9.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1985 (1985.1087.19). © Estate of George Platt Lynes