Can art reconnect us with those we love, even from far away? Siblings Samy Gálvez and Melina Anderson Gálvez immigrated to the United States from Guatemala many years ago and have spent much of their adult lives apart from each other and their family. Knowing Melina was struggling with isolation thousands of miles away during a Mormon mission, Samy wanted to lend support. He wasn’t sure how to do it until one life-changing visit to The Met. Hear how—over the course of a year—sending 100 postcards featuring artworks from the Museum fostered deeper communication and trust between the siblings.

Listen to the podcast

100 Postcards, With Love

Subscribe to Frame of Mind wherever you listen to podcasts:

Listen on Apple Podcasts Listen on Spotify Listen on Amazon Music

Transcript

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

So I’m the youngest of four. Samy is the oldest. It’s boy, girl, boy, girl. But growing up, for sure, my siblings were the loudest, especially Samy, especially during dinner.

Samy Gálvez:

When I think of Melina growing up, I remember all of us sitting around the table and everyone’s just kind of screaming loud and talking and like, blah, blah, blah.

And she would always sit right next to my mom and she would whisper into her ear. And then I was like, “Why are you saying secrets? That’s rude. Like, we’re all here.” She was like, “Well, you guys don’t listen to me. She’s the only one who listens to me.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

So, I didn’t really have a voice at the dinner table. They’re always the loudest and I’m always in the back. Just quiet, just listening.

Samy Gálvez:

I had never had a chance to even get to know her. And I felt like I didn’t really know who she was.

Barron B. Bass:

Samy Galvez and Melina Anderson Galvez are siblings who immigrated to the United States from Guatemala. They have spent much of their lives apart from the rest of their family and from each other. In 2018, they were at opposite ends of the United States—Samy in New York City, getting his master’s in epidemiology, and Melina doing missionary work in California.

Samy knew Melina was lonely, so he decided to reach out and get to know the person she was becoming. Welcome to Frame of Mind, a podcast from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, about how art connects with wellness in our everyday lives. This week, learn how a collection of one hundred postcards from The Met bridges some lifelong gaps between a brother and sister.

Samy Gálvez:

Both my mom and dad are very faithful Mormons or members of the church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

We were not allowed to watch TV or listen to any music on Sunday. We’d go to church at this time.

Samy Gálvez:

So, it was a very, very religious upbringing.

I started to think about it a little more after turning maybe ten or twelve because I was different from everyone else.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

My brother, you know, coming out as gay in his life, he’s gone through very rough experiences.

Samy Gálvez:

While living in Guatemala, homophobia was everywhere. In the Mormon church, certainly, there’s a lot of work to be done.

So, I kind of knew that the type of life I wanted to lead would not happen in Guatemala and the type of opportunities that I wanted to have were not there. And that’s why I decided that I would try to go to college in the United States.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

So, he left.

Samy Gálvez:

When I left Guatemala, she was just eleven and she was just a little girl. There is a picture of her just like bawling her eyes out and holding onto me and saying goodbye. She was wearing a brown shirt and I was wearing a pink shirt. I’m so excited and she’s just so sad. I think she understood that I was leaving.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

He was living in New York City and everything. He’s not a member of the church anymore.

Samy Gálvez:

I moved alone. I moved on my own to New York and so all the coming out process, all the exploring who I am, and becoming who I am was kind of a process that happened independently from my family. I think there was a time when I spent four years without seeing any of them in person. Anyone who’s moved to New York has been lonely. I mean, it really can eat you up sometimes.

Before going to The Met, I don’t think I had ever been to a huge art museum. Because I was able to go in for free, because I was a student, I would just take any opportunity I had to go down and just get lost. I would go maybe once or twice a month, to shift the focus away from me into something greater than myself. And remember how small my problems were and gain a little bit of perspective. Because you can go there and see, like, the Egyptian Wing with art from like 6,000 years ago, to you know, art that is contemporary and modern.

So, you can really see how we have evolved and all the, you know, trials we’ve faced as humans and I would just walk around and walk around, and it became kind of this good place, you know, to go learn and think about life.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Being alone with my parents, when all my siblings moved out, helped me find my own relationship with my heavenly father. I feel like I had the time, I had my parents to ask questions. Really having prayer in my life and the scriptures have helped me realize that God is there.

He has given me peace in times of anguish. He’s given me joy in times of sadness and he always answers my prayers. I decided to serve a mission to preach the gospel to people that are interested. And all of my siblings have served as missions.

Samy Gálvez:

Usually, part of the rules, when you go out on a mission, is that you’re not allowed to talk to your family. And so, you only communicate via letters or email.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

And I was there struggling because I have no idea what I’m doing. I’m far away from my family. It’s mentally exhausting. We’re not really allowed to read any other books outside of those authorized by your leaders, by your church leaders. A lot of people have felt the same way of being lonely.

Samy Gálvez:

And I thought about her and how she was doing. I decided that I wanted to write her during her mission, because I figured, this will be a great opportunity for me to get to know her, to establish a relationship with my sister, and this time, an adult relationship, meaning from one adult to another adult. Then that week, I went back to The Met.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

He knows that I really like art. I like to admire art and just see what makes you feel.

Samy Gálvez:

And I saw at The Met Store that they have these collections of one hundred postcards. One hundred masterpieces at The Met. And when I saw that, I said, “Eureka! This is it!”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

He told me over an email, “I’m sending you something. So be on the lookout for the mail,” and I’m like, “Oh, okay.” And as a missionary, you’re always excited to go check out the mail. It’s, it’s like the thing you do. It’s like, you know what time the mail comes to your apartment complex. You check it every day.

Samy Gálvez:

I don’t remember the first one.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Oh, I found it. It’s this one. It’s a Ganesha statue, which is like an Indian God that controls all obstacles. And he added something that says, “Sometimes we pray so that the obstacles may be taken away in our lives. But I feel like God rarely takes away obstacles. Usually what he does is give us the strength to overcome them. Keep this card because there’s a hundred of them. With love, Samy.”

Samy Gálvez:

And I remember putting the number on the little corner so that I would keep track of how many I was sending to her.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Ganesha was the first of a hundred postcards.

Ganesha statue, 14th–15th century. India, (Orissa). H. 7 1/4 in. (18.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. J. Klejman, 1964 (64.102)

Samy Gálvez:

And so it was really easy for me to just, every morning, wake up and write on my desk. I’d just grab one and spend literally less than a minute writing it up. And then on my way to school, which I was walking to school, just see a little mailbox and just drop it off and I was on my way. And that was that.

So the postcards became quite popular, actually. Her companions would notice that she would get postcards and they were like, “What are these?” and she would say, “Oh, well, my brother went out to New York to The Met and bought these postcards, and he sends them to me every few days, and there’s a hundred of them, and I have, you know, twenty-something, and I’m just waiting for the rest.”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

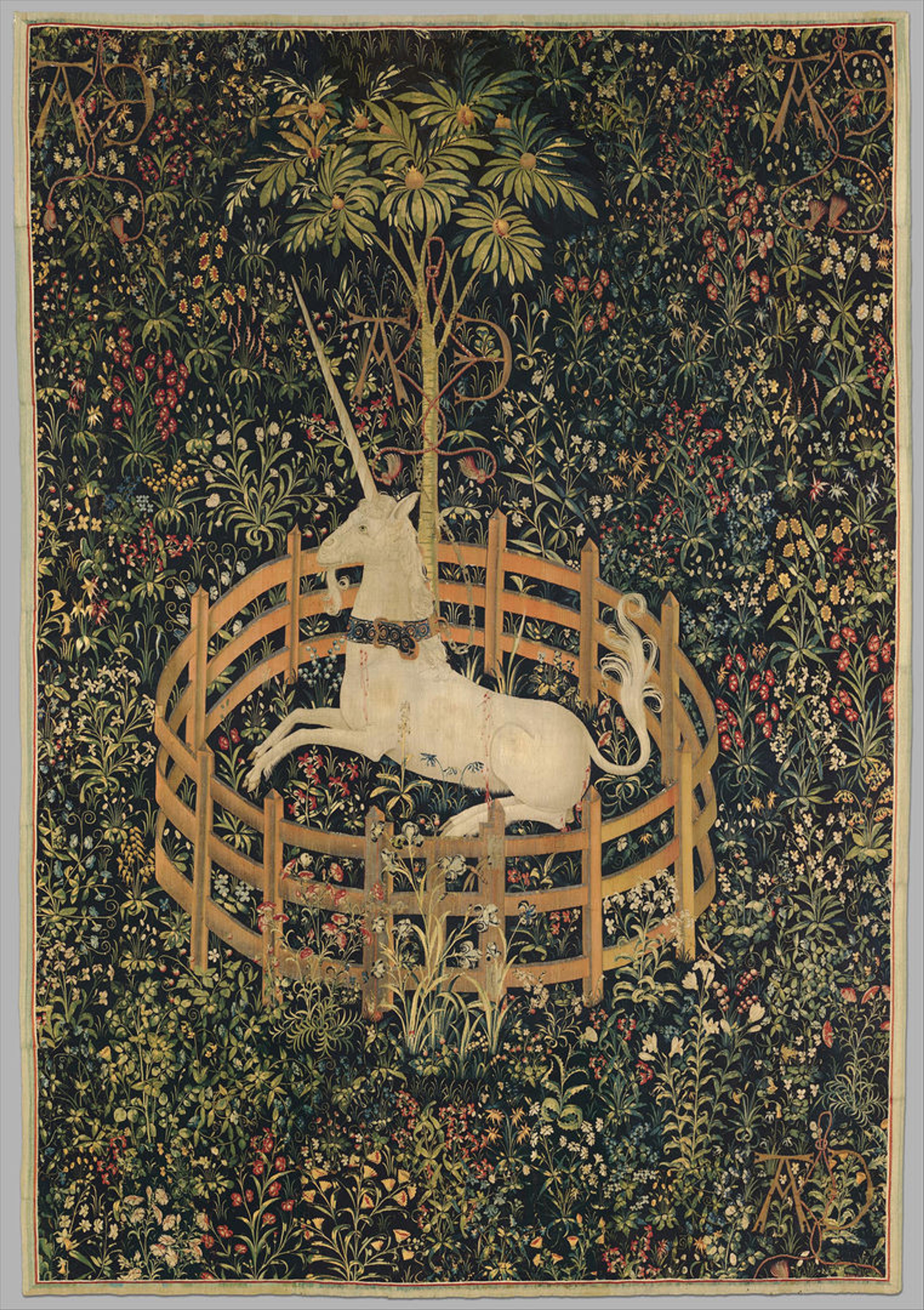

They’ll be like, “Oh, what did he send today?” I think one of the most beautiful ones is the unicorn in captivity. It’s a tapestry. I really like it because it’s this beautiful unicorn, something that might’ve, or might’ve not existed.

Samy Gálvez:

And the unicorn is kind of just sitting there on the grass, surrounded by a fence.

The Unicorn Rests in a Garden (from the Unicorn Tapestries), 1495–1505. Made in Paris, France (cartoon); Made in Southern Netherlands (woven). 144 7/8 x 99 in. (368 x 251.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.6)

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Not tall enough to keep him inside, but enough to just guard him, and around it is tons and tons of different types of flowers.

Samy Gálvez:

And it’s actually chained to a tree.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

A pomegranate tree.

Samy Gálvez:

That is also located inside the fence.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

But it’s also bleeding a little bit from the chains that he’s chained to. And something that Samy wrote was this, he said, “The unicorn is captive, but it is also free. Thus, what is magical is not the unicorn itself but its joy in being found: the love it feels. I love you, Samy.”

I think the unicorn was captive, but it is also free meant to me that in my religion, we have a lot of laws, a lot of commandments to keep, but it is also freeing to keep those commandments. So that’s why it’s so profound to me, just knowing that being free doesn’t mean not having any laws, not having any rules. That’s not what freedom means. It means finding joy within those rules.

We don’t talk about religion that much, but when he sent me those postcards, I think he was writing from a perspective that he had already served a mission and the things that helped him through his mission. So I think it helped me know he’s been there, he’s done this, and so can I.

There was times that he was very depressed, and I could tell by his writing because usually, he would fill out the full postcard. There was times where it was just a couple of sentences and said, “sorry, I’m just having a really rough time.”

Samy Gálvez:

New York was kind of this crossroads for me. It’s when life got real, I remember just wanting to give up. And thinking, I don’t think I can do this anymore. I don’t think I can keep doing this. This is too lonely of a path for me.

And I remember looking at the stack of postcards and thinking, “Samy, just, you know, don’t be a quitter, but at least just finish this project that you started. Just finish writing your sister. And it’s going to be okay by then. Just focus on one day at a time, one postcard at a time, and it’s going to be okay.”

And so I think that kind of helped me be authentic with her. So I would say, “today was difficult, but this thought made me happy.” I remember times when I had to find a reason to write something happy.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

“But I’m still sending you this. Have a good week,” or something like that.

Samy Gálvez:

And I think even though I took the first step, she also took her own steps and she also shared with me. She didn’t write me any postcards, but, but she replied, right? And she would talk back to me and share with me her experiences in her mission.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

I think that sending the postcards not only helped him, but it also helped me, like it helped both of us.

Samy Gálvez:

Writing the postcards was a way for both of us to feel love for each other. You know, choosing to be vulnerable, choosing to on purpose, share our lives, choosing to think of each other. Um, that allowed us to grow closer together and kind of share in our struggles, in our victories, and, uh, to celebrate each other.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

So the very last one he sent me was in the 26th of May of 2018. I was finishing my service as a missionary. One of my favorite movies is, um, Moana. As an immigrant, you know, you leave a place you love to find who you truly are. So it’s just a movie that really resonated with me.

Samy Gálvez:

You know, I swear I did not plan this, but the very, very last postcard that I sent is one that has a beach on it.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

It’s basically just a palm tree, but it’s kind of like in a storm. Even though the winds are so strong, the palm tree is still standing tall.

Winslow Homer (American, Boston, Massachusetts 1836–1910 Prouts Neck, Maine). Palm Tree, Nassau, 1898. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper, 21 3/8 x 14 7/8 in. (54.3 x 37.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Amelia B. Lazarus Fund, 1910 (10.228.6)

Samy Gálvez:

And I thought this is very appropriate because I want to talk about Moana and I want to change the lyrics of the song a little bit. And I wrote the lyrics on the back and I said, “I know a girl from an island.”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Or, “I like to think a little country, like Guatemala.”

Samy Gálvez:

“And she stands apart from the crowd.”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

“She makes her whole family proud. Sometimes the world seems against you. The journey may leave a scar.”

Samy Gálvez:

“But scars can heal and reveal just where you are and the people you have taught have changed you.”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

“The things you have learned will guide you and nothing on earth can silence that quiet voice still inside you. And when that voice starts to whisper.”

Melina Anderson Gálvez/Samy:

“Melina, you’ve come so far. Melina, listen, do you know who you are?”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

“With love, Samy.”

Samy Gálvez:

Um, and that was the last, yeah.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

I felt like I was really changed while I was in my mission, by the people, by the adventure, by every single postcard Samy sent, and he has built me into the person I am today. And also words of encouragement or words of telling me, “I am proud of you. Your whole family’s proud of you.” It’s just very important to hear, you know?

Samy Gálvez:

And it was almost like a must, of like, “Okay, you’re done. Now come over here to New York and let’s go to The Met!”

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

I went to New York for a week, um, and he told me, “Oh, bring all the postcards.”

Samy Gálvez:

And we decided we are going to go to The Met and we’re going to get there as early as we can. And we’re going to go try and find each and every single one of the art pieces in these postcards. And we’re going to take pictures by them.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Samy is a person that does things very fast. Everything’s fast-paced in his life. And we spent the whole day at The Met.

Samy Gálvez:

We walked and walked and walked. We just kept going and going.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

One of the pieces that I was most excited about was the unicorn in captivity because of what he wrote to me. When I first got the postcard, I thought it was a painting. But then when we visited the Met Cloisters, we walked in and we started looking around and then I turned right. And then there was this beautiful, big tapestry. And it just surprised me, because it didn’t seem like a tapestry when I got the postcard. So I saw it and then also, I didn’t think it was this big. The dimension. I don’t know how long the artist took to make that, but that’s the beauty of art, you know, and that’s the beauty of humans that create beautiful things.

It makes us feel connected. It makes us feel like an adventure. It makes us feel loved. That connection of feelings is what makes art so powerful.

Samy Gálvez:

The re-encounter that I was having with my sister was accompanied by the re-encounter that we were having with these art pieces. That meant something to us and that told our story. We finally, I think, had that opportunity to have those conversations as two adult siblings who had now allowed themselves to be vulnerable with each other.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

Even though we have different beliefs, we were still able to find that middle ground or those things in common that we really like, like art, you know, things that just make us go, “Wow.”

We felt like we were new friends. We were new siblings. We found that we had so many things to do together in life.

Samy Gálvez:

The Met kind of had our story in it and it felt weird, almost as if I could go to a piece and like lift it up. And then my words were written in the back.

Melina Anderson Gálvez:

We might feel alone but we can create art still when we’re feeling alone. When you feel just so separated from the world, you can still create something beautiful.

It can be images, it can be paintings, gestures, or things that really mean a lot more sometimes than words. Because people can say whatever they want, but once they’ve expressed it, somehow, that expression is embodied forever in this thing. So it can be a little more powerful than just a word that will fade through time...

Barron B. Bass:

Thank you for listening. This has been Frame of Mind An Art & Wellness Podcast from The Met. To find out more about Samy and Melina and the works mentioned in this episode, please visit The Met’s website at www.metmuseum.org/frameofmind, where you’ll find bonus articles, features, resources, and videos on the endless connection between art and wellness.

Frame of Mind is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Goat Rodeo. At The Met: Head of Content Sofie Andersen, Executive Producer Nina Diamond, Associate Producer Bryan Martin, and Production Coordinators Harrison Furey and Lela Jenkins. At Goat Rodeo: Rebecca Seidel is Lead Producer. Megan Nadolski is Executive Producer. Production Assistance from Char Dreyer, Isabelle Kerby-McGowan, Cara Shillenn, and Max Johnston.

Senior producer is Ian Enright. Story Editing from Morgan Springer. Series Illustration by Sophie Schultz. I’m your host Barron B. Bass. A special thanks to our guests on this episode, Samy Gálvez and Melina Anderson Gálvez.

This podcast is made possible by Bloomberg Philanthropies and Dasha Zhukova Niarchos.

If you liked this episode, please leave us a rating or review and share it with your friends.

Next time on Frame of Mind…

Annie Lanzillotto:

She allowed that into herself, into her soul. She invited it in. And that moment in the light and in those colors was a completely healing, miraculous, transformative experience.