Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor

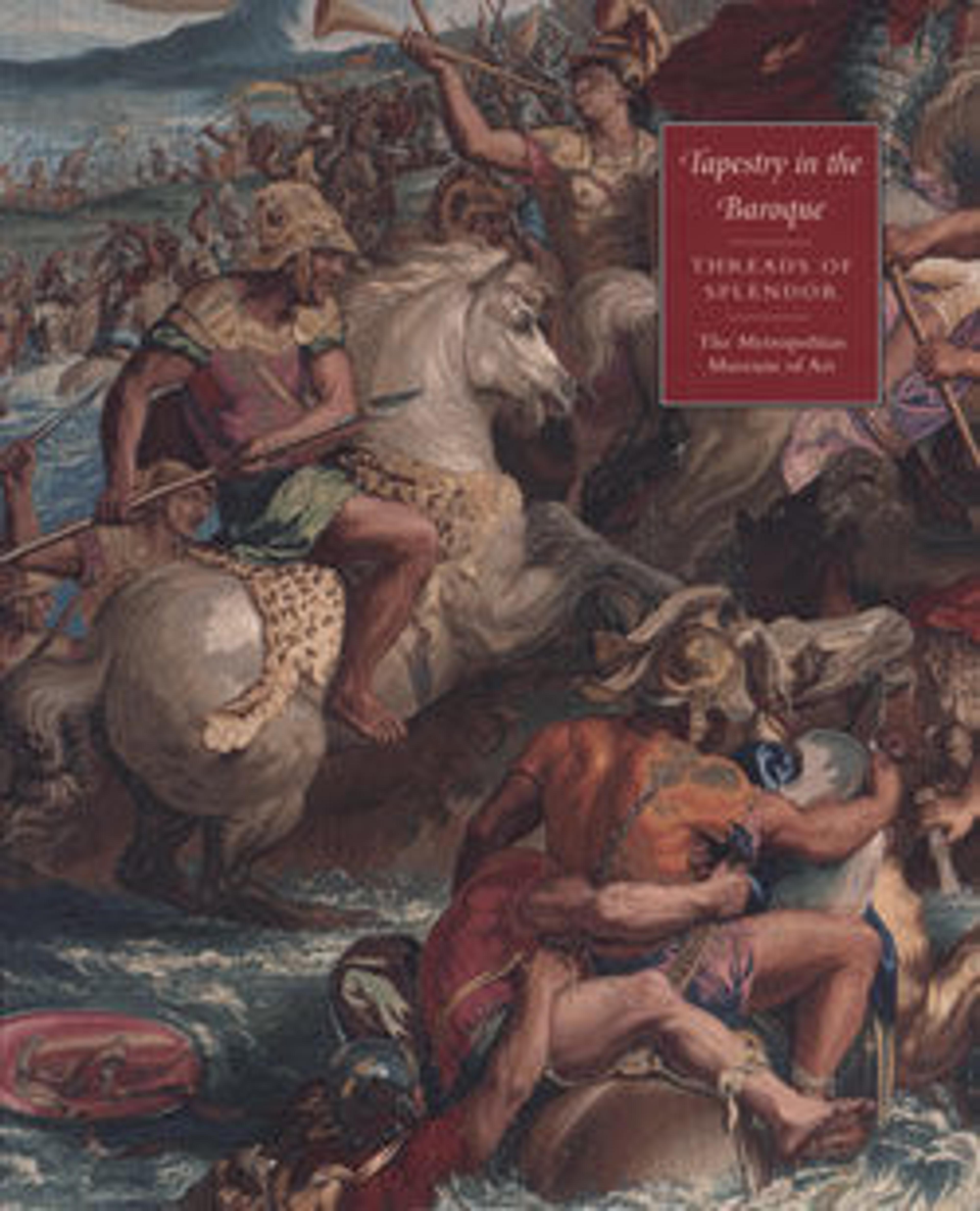

Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor accompanies an exhibition that is the first comprehensive survey of seventeenth-century European tapestry. Conceived as a sequel to Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence (2002), this catalogue is also the first history of Baroque tapestry available in English.

From the Middle Ages until the late eighteenth century, the courts of Europe lavished vast expenditure on tapestries made in precious materials after designs by the leading artists of the day. Yet, the art history establishment continues to misrepresent this medium as a decorative art of lesser importance. Tapestry in the Baroque challenges this notion, demonstrating that tapestry remained among the most prestigious figurative media throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, prized by the rich for its artistry and as a tool of propaganda.

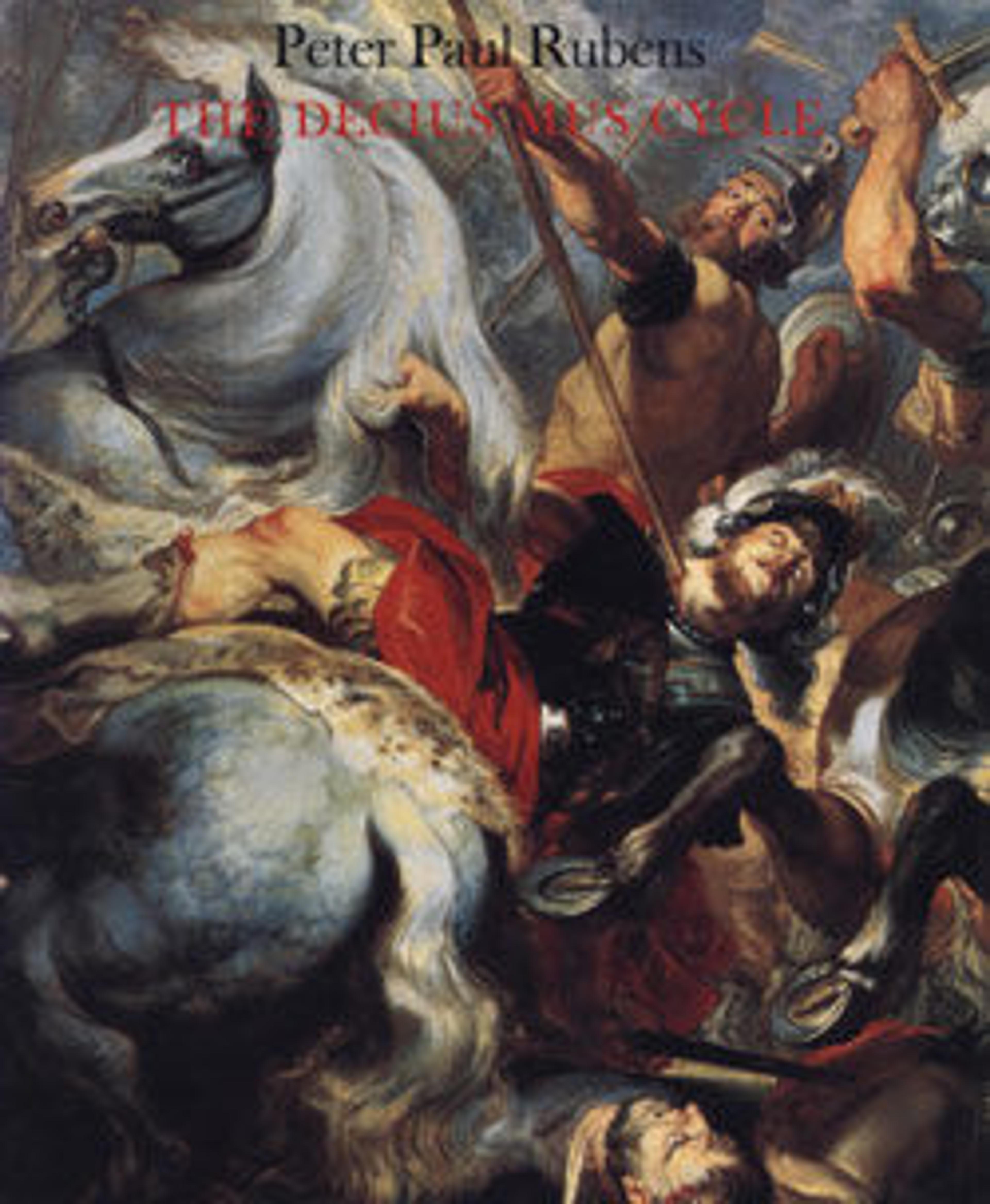

The secondary theme of the study is the stylistic development of tapestry between 1590 and 1720 and the contributions of Flemish, French, and Italian artists as they responded to the challenges and opportunities of the medium in unique and spectacular ways. Divided into chronological sections, the presentation examines the diaspora of Flemish weavers in the 1590s; the foundation of the Paris industry in the early 1600s; the innovative work of Peter Paul Rubens and his circle for the Brussels workshops between 1615 and 1660; the achievements of the Mortlake works for Charles I in the 1620s and 1630s; the parallel development of the Medici and Barberini manufactories in Florence and Rome; the creation of the Gobelins manufactory in Paris for Louis XIV; the development of the Beauvais workshop; and the renewed vigor of the Brussels industry in the 1690s and early 1700s.

Drawing from collections in more than fifteen countries, Tapestry in the Baroque presents forty-five rare tapestries made between 1590 and 1720. About half of these derive from Flemish workshops, including such highlights of the Brussels tapestry industry as the Triumphs of the Church designed by Rubens for the Archduchess Isabella in 1626 and tapestries from the Austrian state collection designed by Jacob Jordaens and others in the 1630s and 1640s. Flemish weavers also played key roles elsewhere in Europe, establishing new enterprises and training native weavers, and the publication also features rare examples from these new workshops, including a stupendous throne canopy made for the King of Denmark in 1584, tapestries made at Mortlake for King Charles I of England in the 1620s, and tapestries from Delft, Munich, Florence, Rome, and Paris. Some of the most ambitious tapestries of the day were woven for King Louis XIV at the Gobelins manufactory, established in Paris in 1662, and the catalogue includes representative pieces from some of the especially celebrated design series. Approximately twenty-five designs and oil sketches by masters such as Rubens, Jordaens, Simon Vouet, Charles Le Brun, Pietro da Cortona, and Giovanni Francesco Romanelli further illustrate stylistic developments in tapestry design during this period.

Met Art in Publication

You May Also Like

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Citation

Campbell, Thomas P., Pascal-François Bertrand, Jeri Bapasola, Bruce White, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), and Palacio de Oriente (Spain), eds. 2007. Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor. New York : New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press.