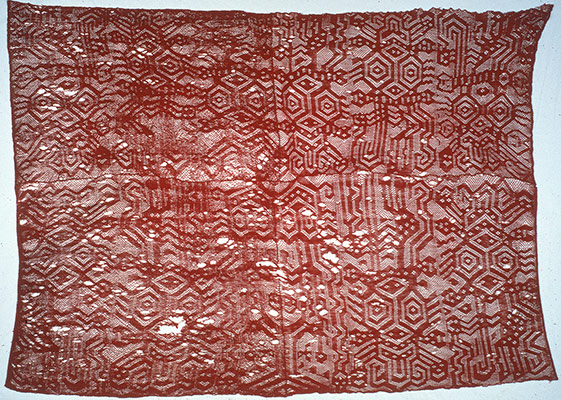

Numerous large architectural complexes exist in the coastal valleys and highlands of Peru. They are used periodically for civic and ritual activities by regional populations living in hamlets and villages of up to several hundred inhabitants. In the first part of the millennium, Chavín de Huántar in the north-central highlands is an influential site. A related set of visual images spreads as far north as Puerto Eten near the modern town of Chiclayo, and as far south as the Nazca Valley drainage. Perhaps based on similar ideologies, its images and symbols appear on local ceramics, textiles, gold, and stone work. For the first time, it is believed, previously unrelated cultures on the northern Peruvian coast and in the highlands have a shared religion. In modern times, these developments have been named Chavín, after the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar in the central highlands. Peoples in the southern Andes—the altiplano of Bolivia, northern Chile, and northwestern Argentina—remain largely outside the range of the unifying influence and develop their own ideology and ritual complex.

In the final centuries of the period, more stratified and warlike cultures emerge, particularly on the north and south coasts of Peru. They introduce new technologies and imagery in art and architecture.