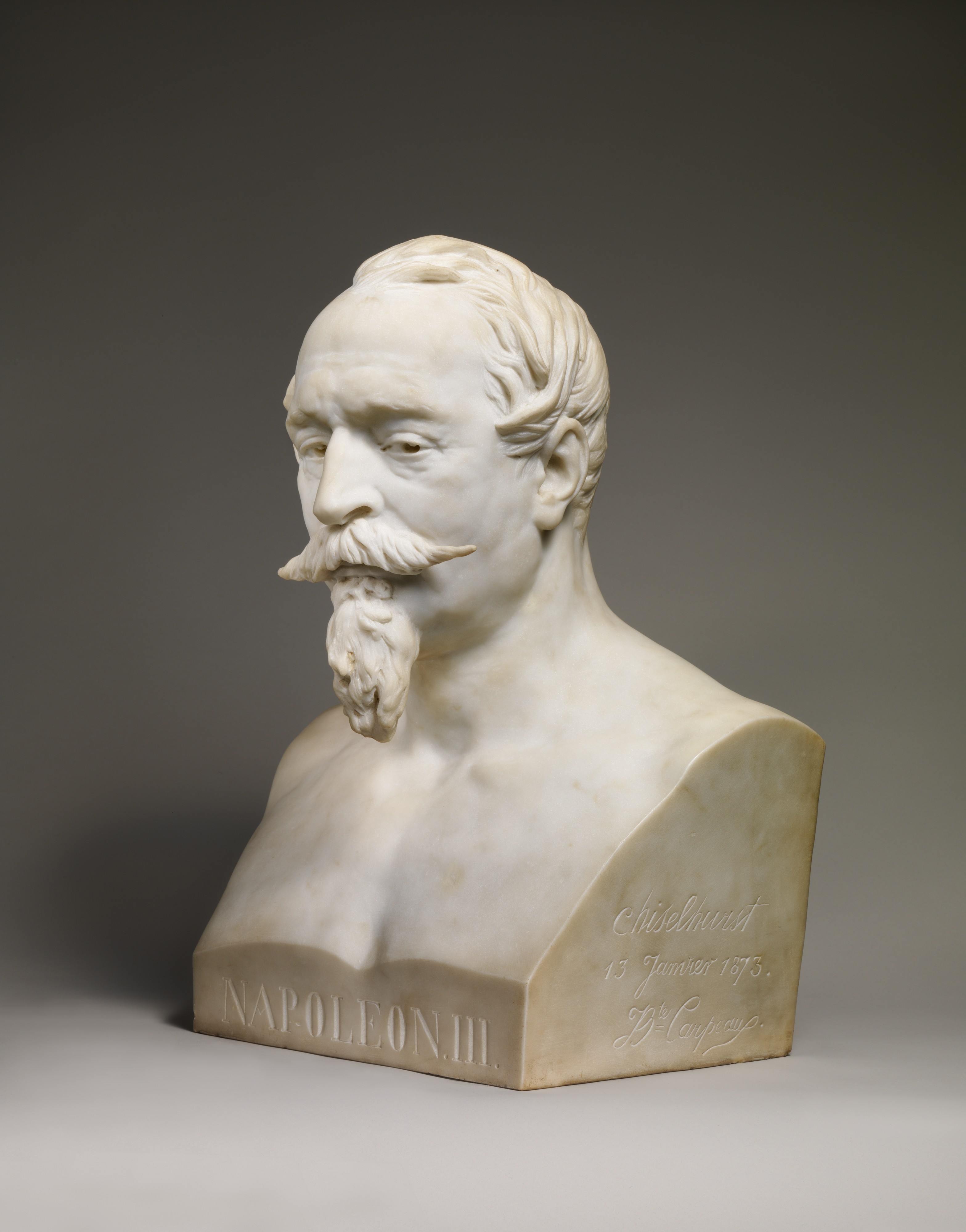

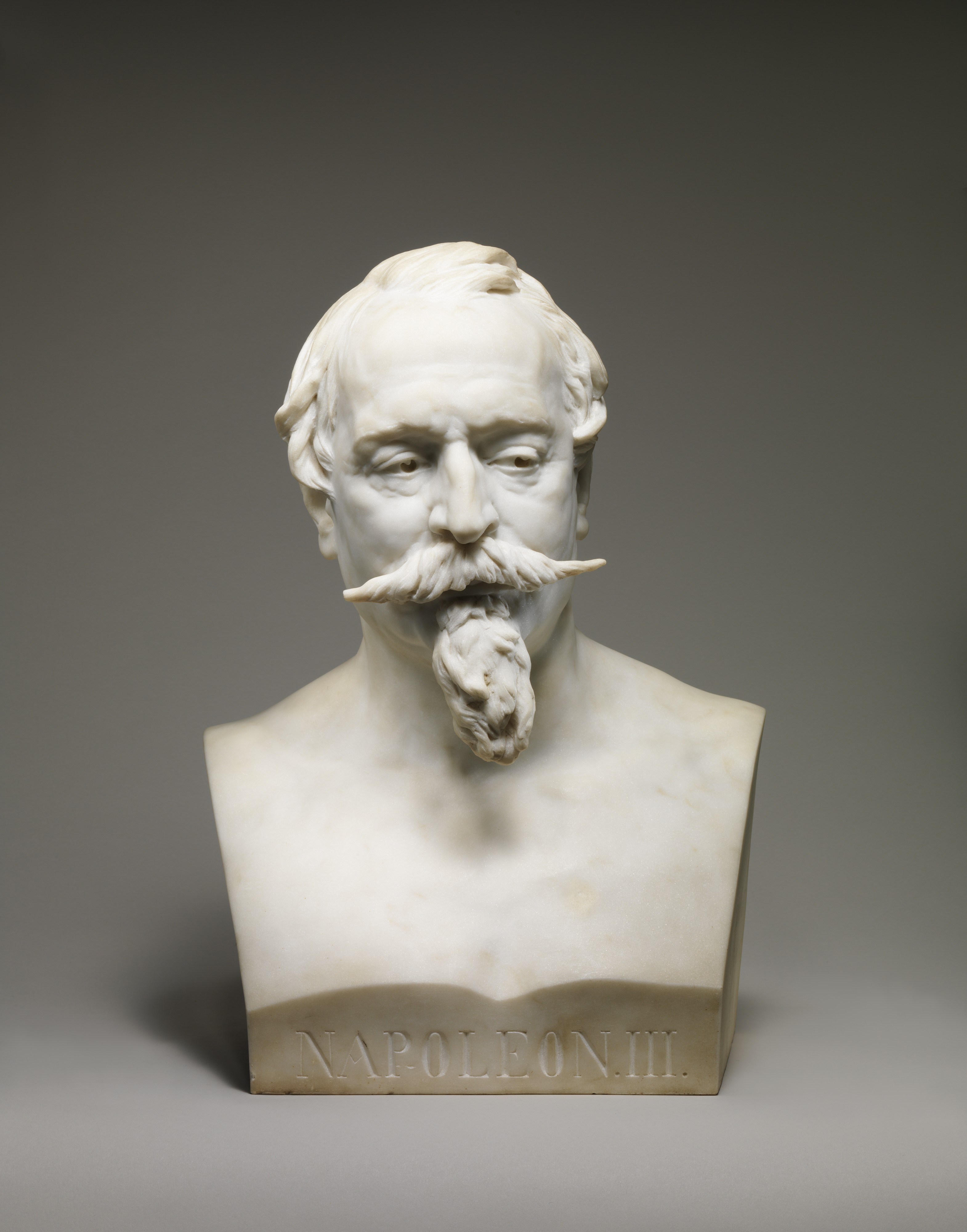

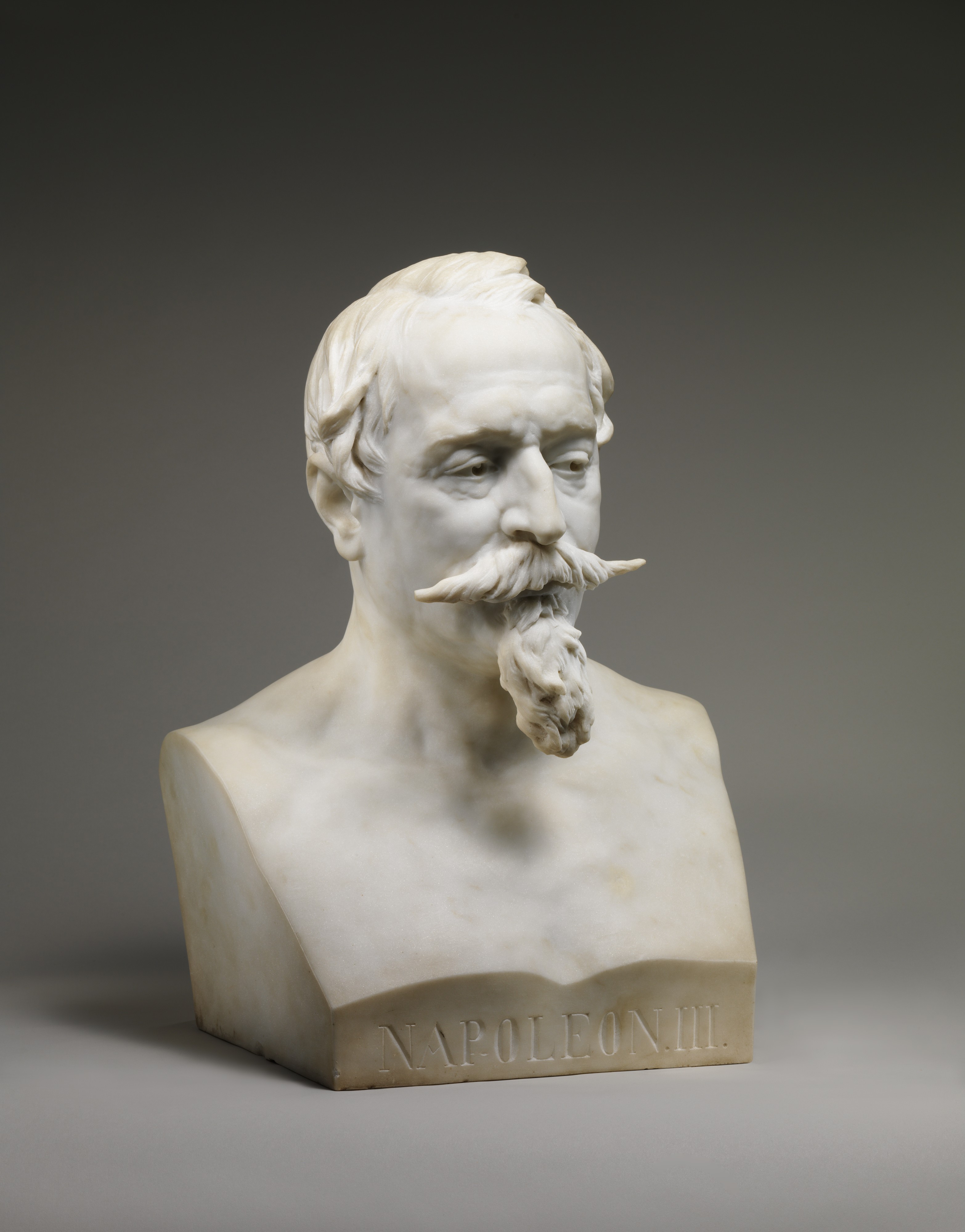

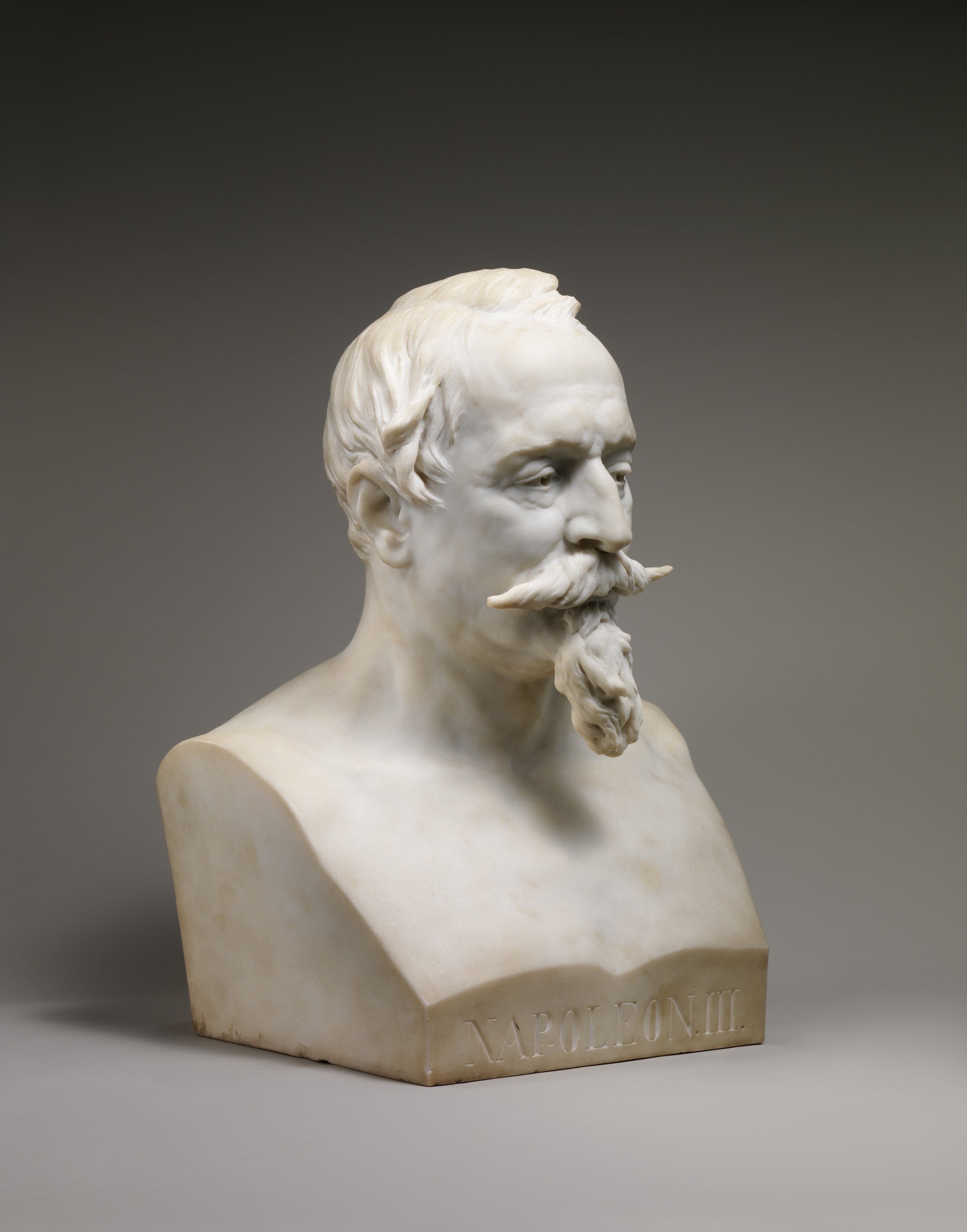

Napoléon III (1808–1873), Emperor of the French

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux French

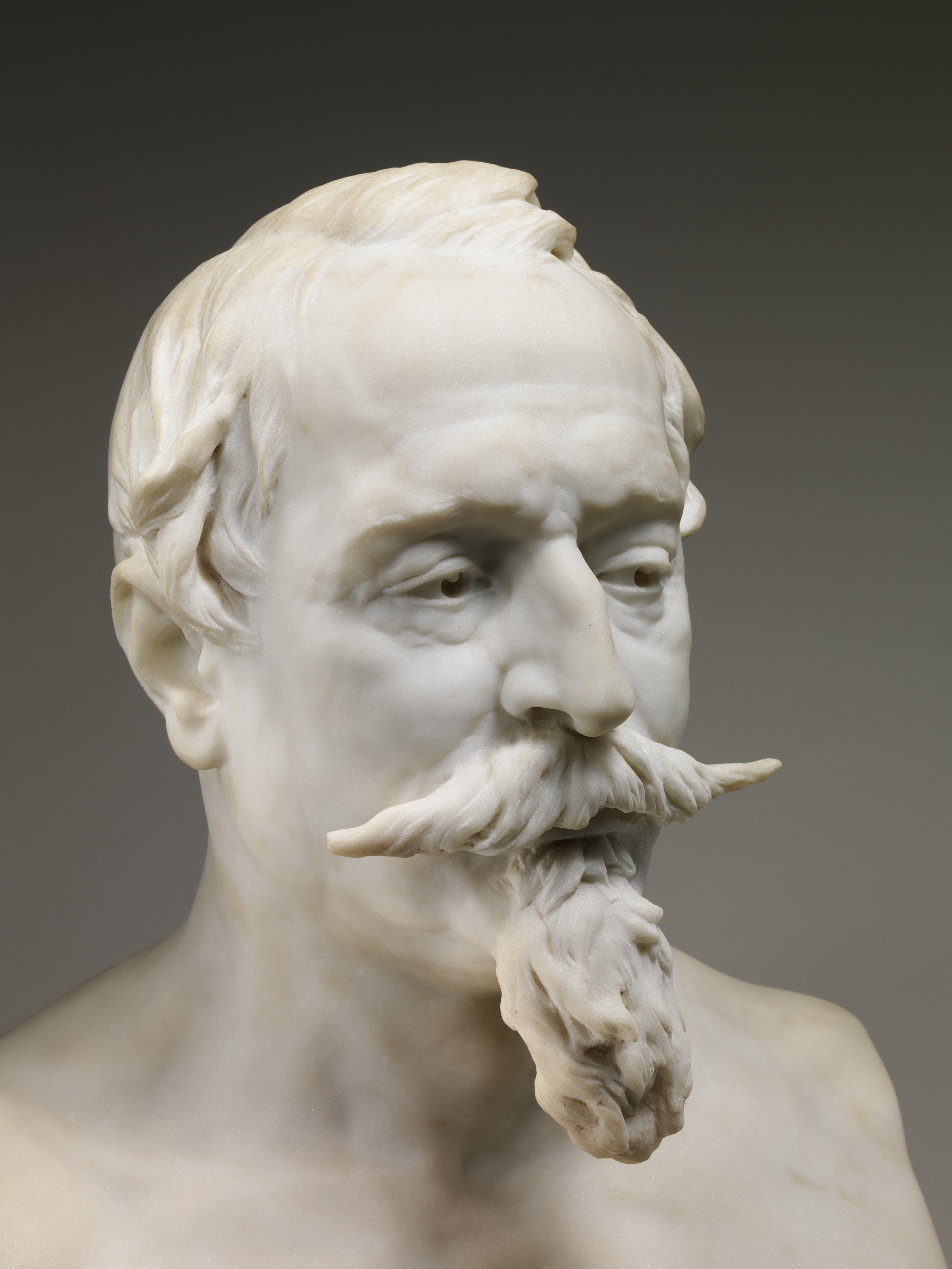

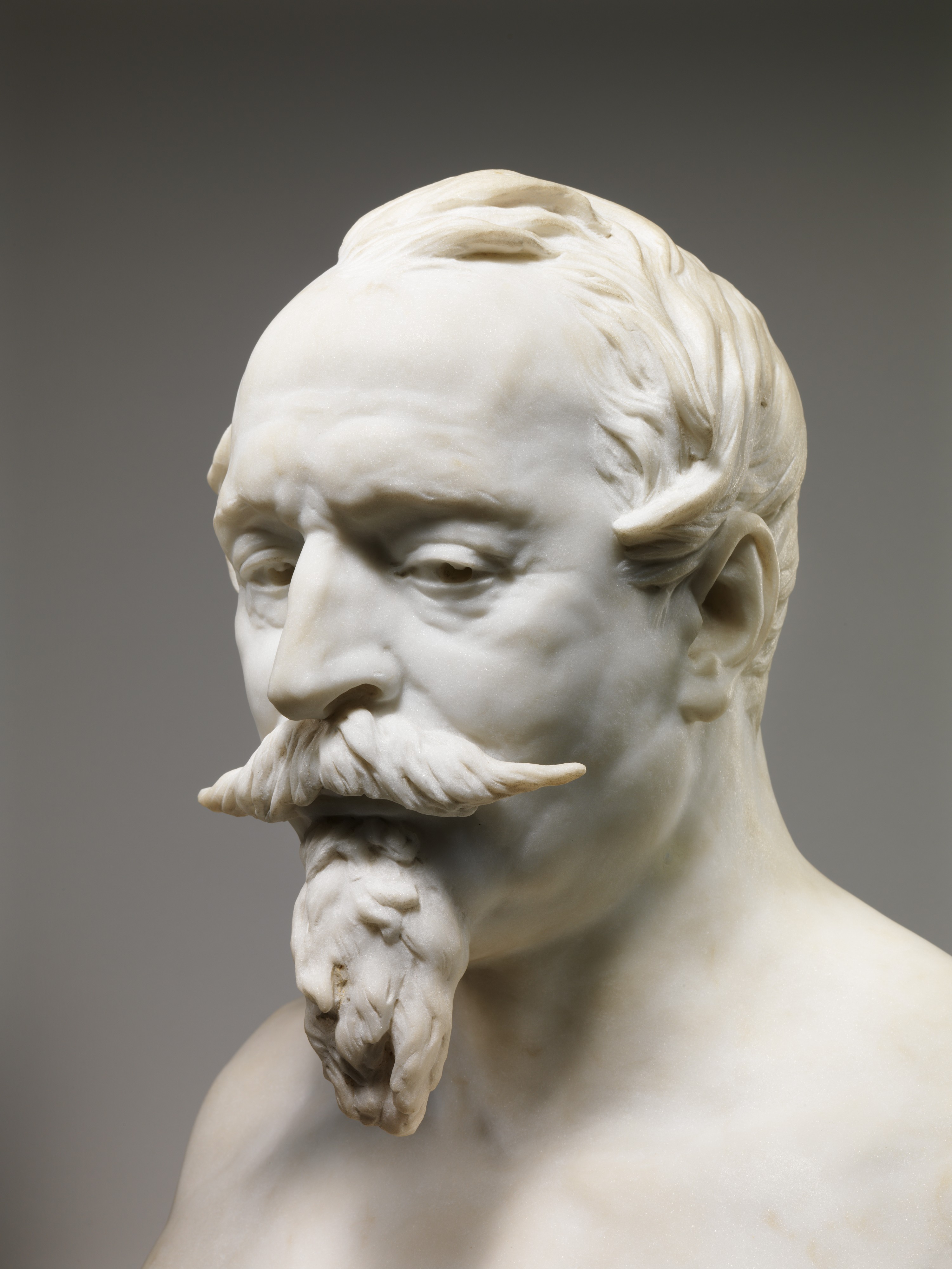

The most successful sculptor of his epoch in france, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux assiduously cultivated the imperial family for the honor of portraying its members. As early as 1852 – 53, he speculatively carved a marble relief of the emperor receiving Abd-al Kader at the Palais de Saint-Cloud and in 1853 – 55 began a plaster group on the theme of the empress protecting orphans and the arts (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes).[1] Despite these initiatives to attract commissions from Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie, it was not until he was asked to do a marble statue of their son, Prince Imperial Louis-Napoléon, and the dog Nero (1867, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) that he became a favorite at court. Subsequently, busts of the emperor’s cousin Princess Matilda Bonaparte and the empress were requested and then issued from Carpeaux’s studio.[2] A number of the artist’s sketches of the family in informal settings and at formal receptions reveal that he had relatively easy access to the court and was familiar with Bonaparte features. [3] Carpeaux did not carve a bust of the emperor, however, until the end of Napoléon III’s life. Finished posthumously, it is one of the most moving and brilliantly executed portraits by the preeminent Second Empire sculptor.

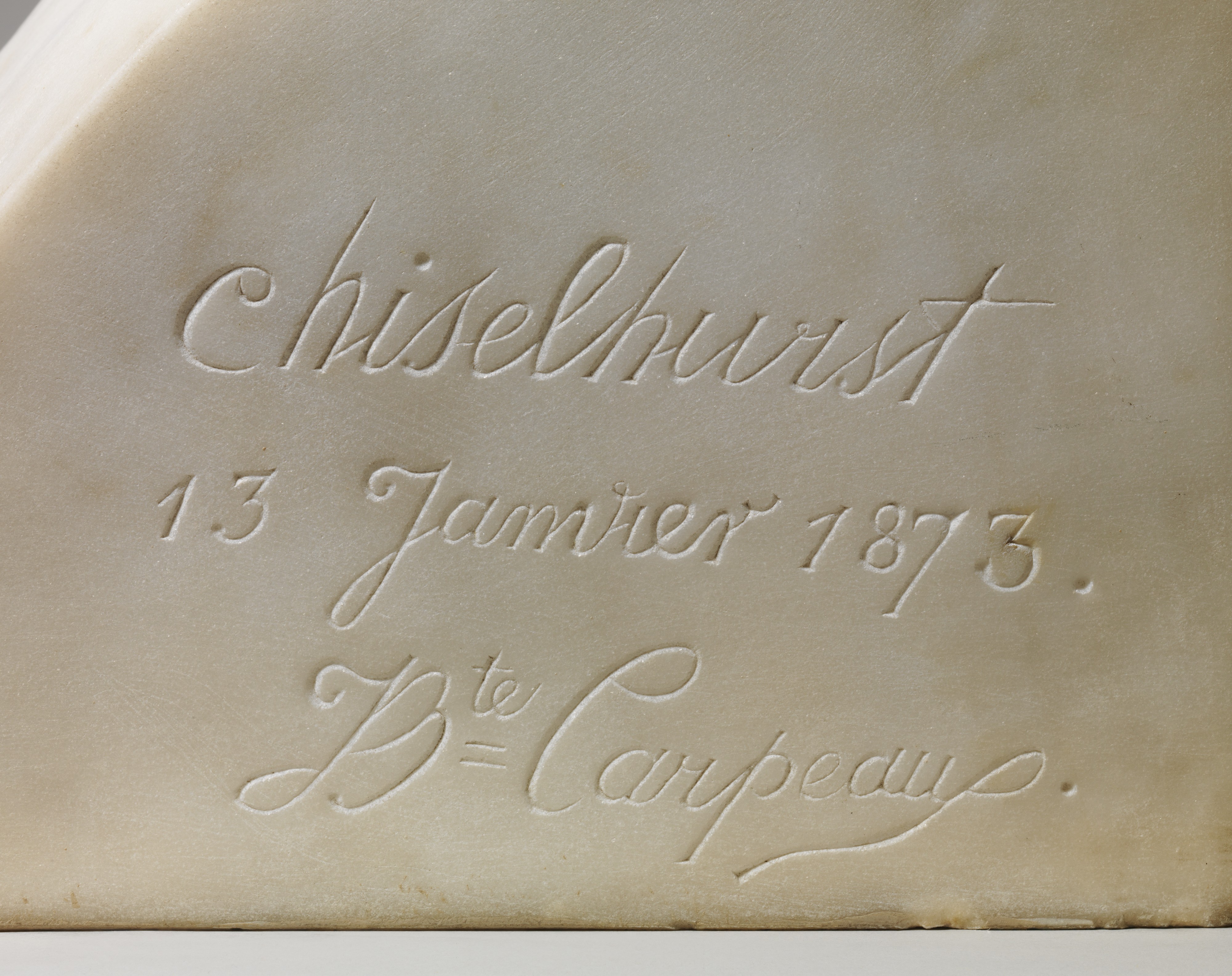

The dramatic circumstances of its commission contribute to its emotional power. In 1871, after Napoléon III sought refuge in England following the events of the Paris Commune, Carpeaux was summoned by Louis-Napoléon to portray the emperor at his retreat at his place of exile in Chislehurst. Back in Paris, having barely begun the project, the sculptor was hastily recalled to England to complete the bust. In the event, he arrived after Napoléon’s death and could only make sketches of the emperor laid out on his funeral bier on January 13, 1873, the date inscribed on the bust. Carpeaux executed a remarkably candid image, devoid of the usual costume and accessories. As Alison McQueen perceptively commented, he was able to deviate from the traditional representation of authority in his characterization of the emperor only because death freed the sculptor from normal con-straints;[4] however, the nude chest clipped into a herm shape recalls classical portrait busts, while the boldly incised name at the front marks this as an imperial image. By their styling, the pointy mustache and prominent goatee identify the period to which the bust belongs. Contrasted with such decisive motifs, the troubled, averted eyes plainly reflect the former emperor’s loss of power after his dethronement. The sagging flesh around the eye sockets and the raised eyebrows, slightly knit together, express hurt and anxiety. In the side view, the locks of hair sweep forward to call attention to the eyes. The marble surface is carved with extraordinary delicacy and precision, rendering a vivid, palpably truthful portrait.

This personal memento of Napoléon III was kept in the private residences of the empress, first at Chislehurst, later at Farnborough, where it presided over the central hallway. Only one other marble example was authorized; it was made from the plaster model for Prince Pavel Demidov, who was closely connected to the family through Princesse Mathilde, divorced wife of Prince Anatole Demidov.[5] Comparing the Museum’s bust to the copy, which lacks its vitality, reinforces the impression that Carpeaux labored personally over the first bust rather than accepting the help of a practicien, a professional marble carver, the typical practice of the busy artist. The Louvre acquired the original plaster for the Museum’s bust in 1895.[6] Several smaller terracottas and plasters were produced by Carpeaux’s atelier for Bonapartists.[ 7] Carpeaux tended to make full use of commercial reproductions of his most famous compositions; the limited edition of this work reflects its personal nature as well as the loss of patronage in the period following the emperor’s deposition. A Carpeaux drawing made in Westminster Abbey at this time bears an inscription "Study for the monument of Napoléon III." [8] Yet, if the sculptor dreamed of executing a memorial to the emperor, this never happened. Instead, Napoléon III was interred in a simple sarcophagus of Scottish granite in the parish church of Saint Mary’s in Chislehurst.

Footnotes:

1. Wagner 1986, pp. 186 – 89, figs. 185, 186.

2. Carpeaux 1975, n.p., "Le Second Empire vu par Carpeaux: Famille impériale, contemporains, événements," and nos. 162, 182.

3. Ibid., nos. 189 – 99.

4. McQueen 2003, p. 43.

5. See Second Empire 1978, p. 218. The present location of the marble that was made for Paul Demidov is unknown.

6. Carpeaux 1975, n.p., no. 147.

7. See, for example, the terracotta bust in the Musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret, Nice (Carpeaux 1980, n.p., no. 79), and the plaster in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (I.N. 1362) (Munk 1993, p. 147).

8. McQueen 2003, p. 40, reviews what is known about this tomb project.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.