Medici vase with a scene of the park at Saint-Cloud (one of a pair)

Manufactory Sèvres Manufactory French

Jean François Robert French

Napoléon I’s (1769–1821) patronage of the arts in France in the early nineteenth century did much to revive the various industries that had suffered during the turmoil of the French Revolution (1789–99), and the Sèvres factory was a major beneficiary of Napoléon’s expenditures on his own behalf and for works of art to be given as diplomatic gifts.[1] The first fifteen years of the nineteenth century saw the development of a new style at Sèvres that reflected the evolving grandeur of Napoléon’s reign as emperor of France, and the richness of the decorative schemes and the scale of many objects distinguish the porcelain of this period from those works produced at the factory during the closing decades of the eighteenth century. In addition, the artistic creativity and technical refinement of Empire- period Sèvres reestablished the factory as one of the most prominent in Europe.

All of the attributes of Sèvres’s finest production of this period are evident in this pair of vases.[2] Their form derives from the famous Medici vase, a marble vase dating to the first century A.D., which was owned by the Medici family by the end of the sixteenth century. While the factory had used variants of this form since its founding,[3] the size of these vases reflects the preference during the Empire period for imposing scale.[4] The vases are decorated with a mottled brown glaze imitating tortoiseshell, known as fond écaille at the factory. While this ground color had been introduced at Sèvres in about 1790, it was rarely used because of the technical difficulties that it posed.[5] The color had to be applied in differing degrees of saturation in order to achieve the varied tonality of real tortoiseshell, and when done successfully, it resulted in an illusion of depth and an almost shimmering surface, as seen on these vases. However, the fond écaille did not adhere as well to convex surfaces as it did to concave or vertical surfaces, which could cause noticeable differences in degrees of tonality, evident on these vases in the contrast between the rounded section of the waist and the vertical areas above it. This minor defect aside, the tortoiseshell ground is an unusually rich foil for the elaborate gilding that is one of the distinguishing features of these vases.

The backs of the vases are decorated with a variety of gilded motifs, the most prominent of which is a pair of confronted griffons separated by a bowl with flames on a tall pedestal (detail, left). Unusually, the motif of the griffons is the same scale as that of the painted reserve on the front of the vase, which gives the gilded decoration on the vases an atypical prominence. The gilding is further emphasized by the subtle but extremely effective contrast between the matte and burnished areas, creating a remarkable degree of both definition and nuance in all of the motifs. These vases reflect a relatively rare instance in which the gilding plays a major rather than merely supporting role in the visual impact of the overall decorative scheme.[6]

The front of each vase is painted with a large reserve depicting Napoléon and an entourage in an informal outdoor setting. In one vase (MMA 2011.545), Napoléon rides in a carriage with the Empress Marie- Louise (1791–1847) and another female, perhaps Princess Pauline (1780–1825), Napoléon’s sister.[7] Among the entourage accompanying the carriage is Roustam Raza (ca. 1782–1845), Napoléon’s mamluk bodyguard, who is recognizable by his distinctive turban. The carriage passes in front of the south wing of the Château de Saint- Cloud, seen behind the elaborate fountain known as the Bassin du Fer-à-cheval.[8] On the second vase (MMA 2011.546), Napoléon is depicted riding with companions, including Raza, in the Parc de Saint- Cloud with the hills of Bellevue and Meudon in the distance. The riders are about to embark on a hunt and wear the green livery of the imperial hunt.

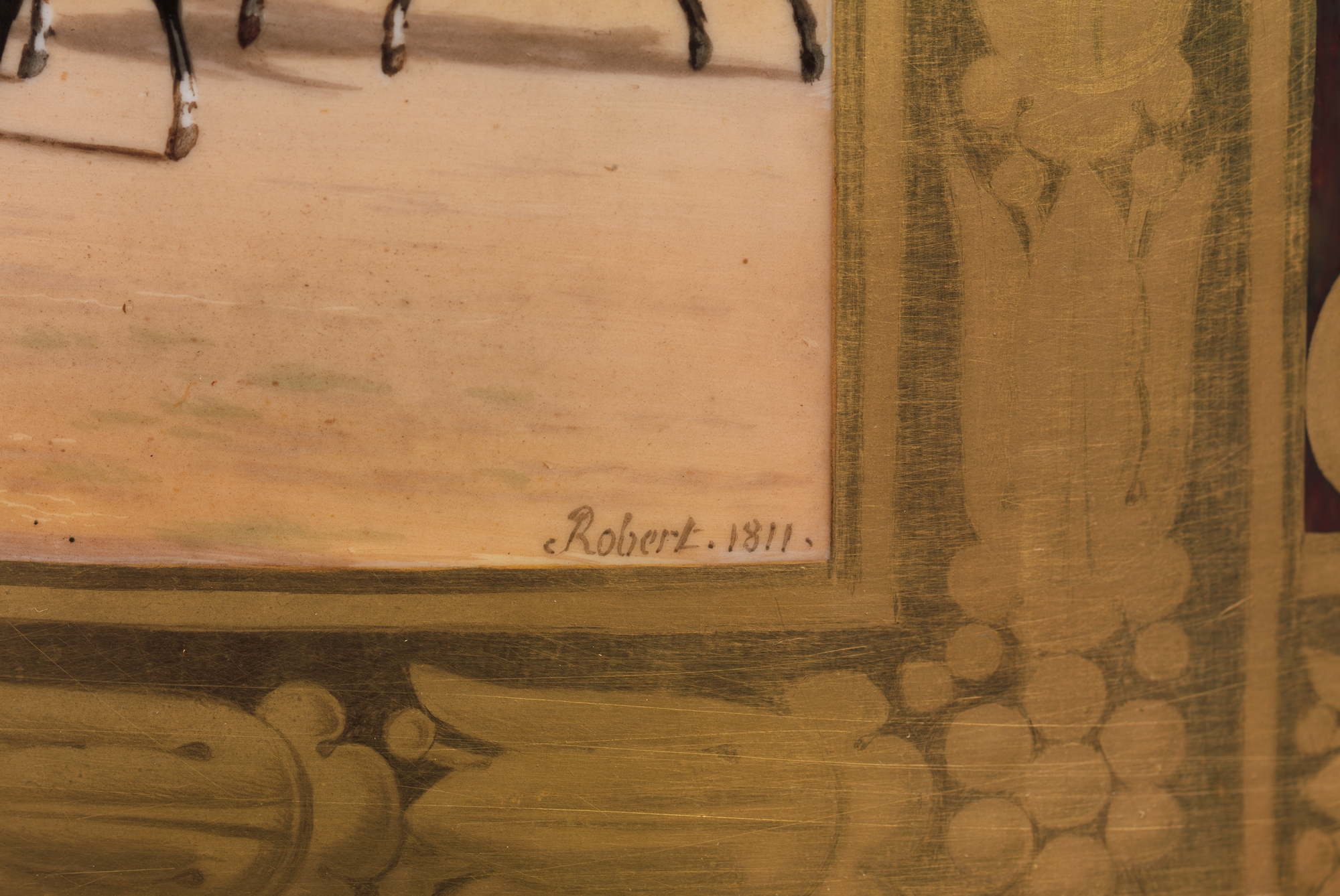

Both reserves are signed “Robert,” indicating that they are the work of Jean- François Robert (French, 1778–1832), one of the most talented painters at Sèvres in the early nineteenth century. Robert painted on canvas as well as on porcelain, and he frequently exhibited in the Salons, which were an integral part of official artistic life in Paris.[9] Robert specialized in landscapes and hunting scenes, and his proficiency in the latter area prompted Alexandre Brongniart (French, 1770–1847), director of the Sèvres factory, to request permission for Robert to attend the imperial hunts in order to sketch them.[10] Robert was one of the few painters at Sèvres who frequently created his own compositions rather than simply copying those provided to him on porcelain. Robert’s skill as an artist brought him the patronage of Élisa Bonaparte (1777–1820), Grand Duchess of Tuscany and sister of Napoléon, as well as Charles- Ferdinand de Bourbon (1778–1820), duc de Berry, who appointed Robert as peintre des chasses (painter of hunts) in 1819. Robert’s abilities as a porcelain painter are evident in the two reserves on these vases, which are simultaneously very detailed and highly atmospheric. The skillful handling of light in particular creates an impression of great depth in the landscape in the hunt reserve and makes the sky a major compositional element in the reserve depicting Saint-Cloud.

The subjects of the two reserves were almost certainly chosen to appeal specifically to Napoléon. A letter written in 1810 by Pierre Daru (French, 1767–1829), the head of the imperial household, noted that “His Majesty seemed to take pleasure in paintings on porcelain representing landscapes in the environs of Sèvres, St-Cloud, and other imperial palaces, decorated with His Majesty’s promenades and hunts.”[11] This known preference on the part of Napoléon must account for the selection of these two more informal compositions on the Museum’s vases rather than the more traditional official portraits customarily found on objects of this scale and importance.

The informal depictions of Napoléon would have made the vases seem especially appropriate to include among the large gift of works of art sent to Jérôme Bonaparte (1784–1860), the emperor’s youngest brother, on February 12, 181.[12] Napoléon had named Jerome the king of Westphalia in 1807, and after Jérôme’s marriage to Princess Catherine of Württemberg (1783–1835), the royal couple established their residence in Kassel, the capital of Westphalia. The shipment of art sent to Jérôme included numerous pieces of Sèvres porcelain, and the value of all the works of art exceeded the enormous sum of 43,000 francs.[13] It is likely that the vases remained in Kassel only a short time, however, because Jérôme and Catherine were forced to flee Westphalia due to Napoléon’s military defeats in 1813. They eventually settled in Florence, presumably with many of their possessions, which reputedly filled one hundred and fifty wagons when they left Kassel.[14]

The vases almost certainly accompanied the royal couple to Florence, because they appear in an 1880 auction held at the Villa of San Donato, located outside of Florence. Mathilde Bonaparte (1820–1904), the only daughter of Jérôme and Catherine, married Anatole Demidov (1812–1870), the enormously wealthy Russian entrepreneur and art collector, in 1840. Although Mathilde and Anatole separated several years after their marriage, it appears that Anatole kept many of the Bonaparte family possessions, including the vases. At the time of the marriage, Demidov had paid Jérôme a substantial sum with which to settle the latter’s debts, and Demidov acquired many of the family’s works of art in return.[15] Anatole died in 1870, and with no children from the marriage, he made his nephew Paul the heir. Paul held a series of auctions from the Villa of San Donato in 1880, from which the Museum’s two vases were sold as number 122.[16]

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 See, for example, Tamara Préaud in Préaud et al. 1997, no. 141, pp. 354–55.

2 The pair of vases has been published in greater depth by the present author in Munger 2015.

3 See Préaud and Albis 1991, pp. 158–59, no. 135.

4 An earlier example of a Sèvres vase of enormous scale derived from the Medici vase is the Grand Vase of 1783, now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris (OA 6627).

5 I am grateful to Tamara Préaud for this observation.

6 It is almost certain that the gilding on the vases was executed by both Francois- Antoine Boullemier (French, 1773–1838), known as Boullemier the Elder (Archives, Cité de la Céramique, Sèvres, Vj’ 17, fol. 38, September 1810), and his brother, Antoine Gabriel Boullemier (French, 1781–1842), known as Boullemier the Younger (Archives, Cité de la Céramique, Sèvres, Vj’ 17, fol. 39, April and May 1810).

7 Cyrille Froissart, a ceramics expert in Paris and consultant to the 2011 sale at Sotheby’s, suggests this identification. See entry for these vases in Sotheby’s 2011, no. 178.

8 This same scene, with minor variations, was painted by Robert on an ice pail of 1811 now in the British Museum, London, and on a porcelain tabletop executed between 1813 and 1817; see Munger 2015, p. 309.

9 Robert first participated in the Salon of 1812, where he exhibited three landscapes (Landon 1812, vol. 2, p. 70), and he continued to exhibit at the Salon through the 1820s (Bellier de La Chavignerie and Auvray 1882–85, vol. 2, p. 394).

10 Préaud in Préaud et al. 1997, p. 193.

11 Quoted by Préaud in ibid.

12 Archives, Cité de la Céramique, Sèvres, Vbb 4, fol. 7, February 13, 1812.

13 For a description of the shipment, see Roth 1995, pp. 2–4.

14 Ibid., pp. 3–4.

15 Haskell 1994, p. 19.

16 Catalogue des objets d’art et d’ameublement 1880, pp. 29–30, no. 122. The purchaser of the vases at the Villa of San Donato sale is not known, and the next known appearance of the vases is in 1963; see Palais Galliera 1963, no. 39.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.