Stolen Treasure: Art and Archives at Neuschwanstein Castle

Unidentified photographer. View of Neuschwanstein Castle, 1945. Thomas Carr Howe papers, 1932–84. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

On May 4, 1945, James Rorimer, the future director of The Met, arrived with a small group of American troops at a "fairy-like castle" in southwest Germany, built in a "fantastic pseudo-Gothic style. . . ." In his wartime memoir, Survival: The Salvage and Protection of Art in War, the lieutenant describes in vivid detail the conditions he and his fellow soldiers encountered that day at Neuschwanstein:

Works of art were everywhere. . . . Confusion indicated that this repository was being emptied when the Nazis had vanished a short time before the arrival of our troops. Here, and on the floors below, racks and specially prepared rooms recently plastered had been fitted with paintings, rare furniture, tapestries, and other treasures confiscated from France. . . . In several of the rooms we found the art libraries of Paris collectors. Thrown behind and between the books were rare engravings, drawings and paintings.

Rorimer was a Harvard-educated medieval art specialist. Appointed curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1934, he played a central role in the development of The Cloisters, the branch of the Museum in upper Manhattan devoted to the art and architecture of medieval Europe. In 1943, Rorimer left The Met to join the United States Army, where he became an officer in the Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives program (MFAA) that was established in late 1943 under the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies.

"Monuments Man" First Lieutenant James J. Rorimer (left) and Sergeant Antonio T. Valin examine recovered objects. Neuschwanstein, Germany, May 1945. Photograph by U.S. Signal Corps, James Rorimer papers, National Gallery of Art

The soldiers in this program—commonly known as Monuments Men—included museum curators, art historians, and others trained to identify and care for artworks that were subject to harsh conditions. In addition to Rorimer, several others were also Metropolitan Museum staff members or joined the Museum after the war, among them Theodore Heinrich, Theodore Rousseau, Edith Standen, and Harry D. Grier.

These Monuments Men—approximately 345 men and women from thirteen nations—worked individually and in small teams to protect artworks, archives, and monuments of historical and cultural significance as the Allied forces advanced across Europe. They also helped secure artworks looted by the Nazis, many of which were restituted to their rightful owners after the war.

In his pursuit of art treasures confiscated and hidden by the Nazis, Rorimer covered a broad territory between northern France and Germany between 1943 and 1946. Among other things, he was directly involved with the discovery of the Nazi art repositories at Heilbronn and Berchtesgaden.

File cabinets containing ERR records of looted artworks, Neuschwanstein castle, May 1945. National Archives and Records Administration

But one of his greatest achievements was his discovery and preservation of archives that documented Nazi art looting during World War II, including the one that he stumbled across, that day in May, at the castle near Füssen in the Bavarian Alps.

On his first visit to the castle on May 4, Rorimer took notes (left). Surveying the castle quickly, he recognized jewelry looted from the Rothschild family, silver from the David-Weill collection, and rare manuscripts.

Meanwhile, in another wing of the castle, the soldiers discovered an ERR laboratory where artworks were photographed, along with file cabinets containing catalogues and records of thousands of objects looted from France (above).

The ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg) was a Nazi task force led by Alfred Rosenberg that was responsible for plundering thousands of artworks in nations occupied by Germany during World War II. The ERR established numerous storage repositories for looted art, including the one at Neuschwanstein, where they moved several large collections taken from Paris during 1941–45.

Such repositories were accompanied by photographs, catalogue cards, and other records that the Nazis created in the 1930s and 40s to help organize their plunder.

Understanding immediately the immense value that the meticulous documentation stored in the castle would have for the work of restituting looted artworks to their original owners, Rorimer ordered that records room be locked.

"As a field expedient," he later explained, "I took one of the antique Rothschild seals—SEMPER FIDELIS—and sealed the doors with sealing wax and cord."

Left: Military field notes of James Rorimer, May 4, 1945, the day he discovered ERR documents at Neuschwanstein Castle. James Rorimer records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

Extracts from James Rorimer Field Report on Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives, June 3, 1945. MFA&A Field Reports, 1943–1946, [AMG–159], Records of The American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, Record Group 239, National Archives and Records Administration

One month later, in a report that summarized the ongoing effort to protect valuable archives (above), Rorimer observed that "almost all of the documents, catalogues, and photographic negatives of the Einsatzstab Rosenberg ... now at the Castle of Neuschwanstein.... can be the nucleus for the work of restitution of works of art and should be kept together" (June 3, 1945). Today, these archives are uniquely valuable resources that researchers study to understand the provenance of looted art.

In addition to recovering artworks and archives, Rorimer helped to establish the Munich Central Collecting Point (MCCP), through which thousands of artworks were returned after the war to countries from which they had been looted. For many objects stolen by the Nazis, passage through the MCCP was the first step on the path to restitution to their rightful owners.

After the war, Rorimer continued his distinguished career at the Metropolitan and served as its director from 1955 until his death in 1966. Under his leadership, The Met acquired many important artworks.

In a fascinating coincidence, one of the artworks the Museum acquired was a leaf from a Persian manuscript that Rorimer had first encountered at the castle at Neuschwanstein.

"Fable of the Lion and the Hare," folio from a Kalila wa Dimna, ca. 733–1333 AD. Attributed to Iran, Shiraz. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Painting: H. 4 1/8 x 7 1/4 in. (10.5 x 18.4 cm); Page 13 1/4 x 8 5/8 (33.7 x 21.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1959 (59.7)

This folio, which was probably created in the late fourteenth century in what is now southern Iran, displays an illuminated scene from the "Lion and the Hare," a fable from the Kalila wa Dimna. By the 1930s, the sheet had been acquired by Alphonse Kann, a French art collector of Jewish heritage. Kann fled France for England in 1938, leaving his valuable art collection behind.

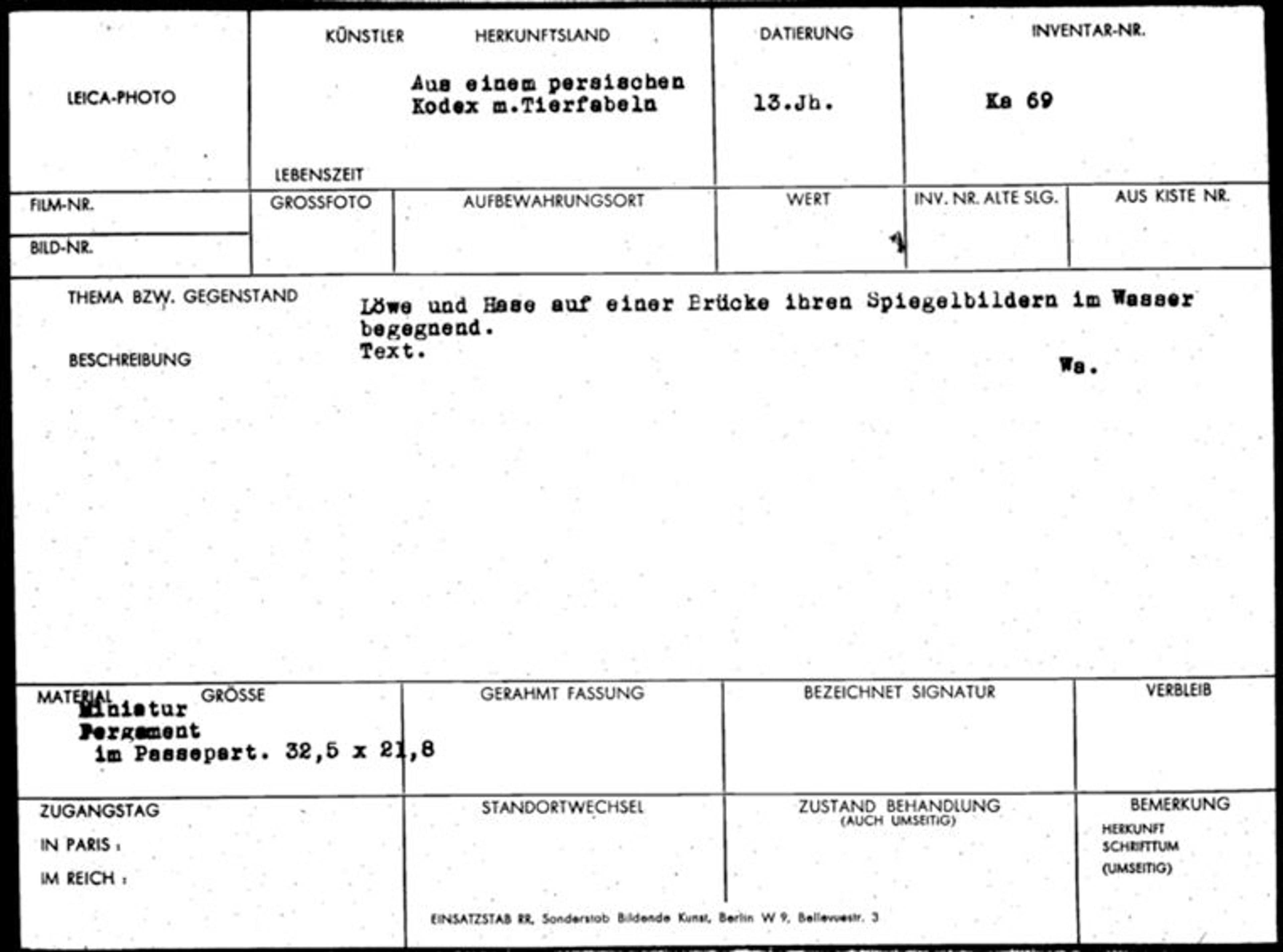

ERR inventory card for "Fable of the Lion and the Hare," folio from a Kalila wa Dimna. Plundered by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed via the Database of Art Objects

Kann's collection was seized by the ERR in 1940. The Germans assigned the folio the inventory number Ka 69 (above) and transferred it to Neuschwanstein, where it was recovered by Rorimer and his colleagues in 1945. The Monuments Men ensured its return to France in November of that year, and two years later the folio was restituted to Kann by the Commission de Récupération Artistique. The manuscript later appeared on the art market and was purchased by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1959.

Today, the folio is one of several artworks now in the Museum's collection that were looted by the Nazis, restituted to the original owners or their heirs after the war, and later legally acquired by The Met.

In 1998, forty-four governments signed the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art to assist in identifying and resolving issues relating to art confiscated by the Nazis. Ever since then, archival research has played a pivotal role in the identification and restitution of looted artworks.

Archives also serve as a foundation for American museums to share information about the ownership histories of objects in their collections. Provenance researchers at The Met consult documents in the Museum's own archives, along with primary sources held by other institutions, such as the United States National Archives and Records Administration, the Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv) of Germany, and the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (MAEE) of France.

Documents in some of these archives are now accessible online through search portals, such as the Database of Art Objects Plundered by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) and the Deutsches Historisches Museum Database on the Munich Central Collecting Point.

These historical records, which support the work of art historians and other researchers, are available today largely thanks to the heroic efforts of Allied military personnel such as James Rorimer, who recovered and safeguarded them in Europe during the final months, and the aftermath, of World War II.

Further Reading

Rorimer, James J. Survival: The Salvage and Protection of Art in War (New York: Abelard Press, 1950)

Provenance Research Resources

A portal to historical documents and provenance research projects at The Met, across the United States, and abroad.

James Moske

James Moske is the managing archivist in the Museum Archives.