Watercolor

Clockwise from upper left: brushes, watercolor cakes, porcelain palette, components of watercolor (powdered pigment, gum arabic and water), tubes of watercolor, sponge, knife

Prized for the luminosity of its transparent colors, watercolor is a water-based medium that is applied by brush, typically to white paper. Packaged in cakes of color known as "pans," or in tubes of thickened paint, it is composed of finely-ground pigment combined with water and gum arabic, a binder that disperses the pigment particles to create a uniform solution and adheres it to the support. Modern watercolors form washes with only a touch of water, allowing greater ease of use.

The watercolor palette comprises a vast range of pigments. These include colors made from natural minerals, resins, or vegetables; for example, the "earths" (such as ocher and burnt umber), azurite, terre verte, madder root, and gamboge. Artificial colors processed from minerals include Prussian blue, vermilion, lead white, and cadmium yellow. Starting in the late nineteenth century, manmade organic colors were synthesized in laboratories to produce brilliant hues that range from oranges to violets and mauves.

The underlying support plays an extremely important role in watercolor; the brightness of a white sheet of paper, parchment, or ivory (used in the past for miniatures), contributes to the jewel-like quality of the transparent colors. For this reason, colored paper is rarely employed for this medium. Paper treated with gelatin sizing (a liquid compound that makes it less absorbent) is generally used for watercolor. Sizing prevents the medium from penetrating the sheet and allows for more precise brushwork. Artists seeking a more fluid effect in which colors merge may use highly absorbent Japanese papers, unsized sheets, or papers dampened with water, the latter effect seen in the Winslow Homer detail below.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). Flower Garden and Bungalow, Bermuda (detail), 1899. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper, 13 15/16 x 20 15/16 in. (35.4 x 53.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Amelia B. Lazarus Fund, 1910 (10.228.10)

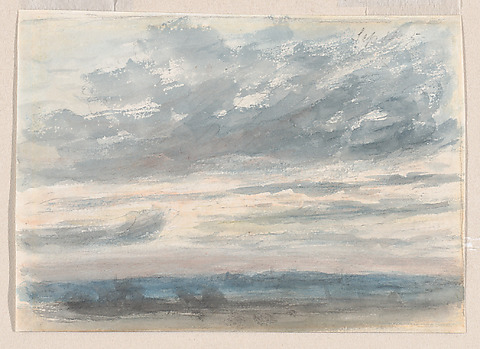

Applied with a soft pointed brush or flat profile brush, watercolor is distinguished by the diversity of its strokes and the many ways that the dry and wet paint can be manipulated to form a broad array of effects. For example, applying it to dampened paper or over a wet wash will produce flowing passages of color with diffuse cloud-like edges, or tidelines, as it dries.

Applying watercolor to a dry sheet or on top of dried color will produce more well-defined effects, such as in this detail from The Watzmann by August Heinrich:

August Heinrich (German, 1794–1822). The Watzmann seen from the North-East, and Some Sketches of a Mountain (detail), 1820–22. Watercolor over a sketch in charcoal, 6 1/8 x 9 7/8 in. (15.5 x 25.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Charles and Jessie Price, and PECO Foundation Gifts, 2009 (2009.124a, b)

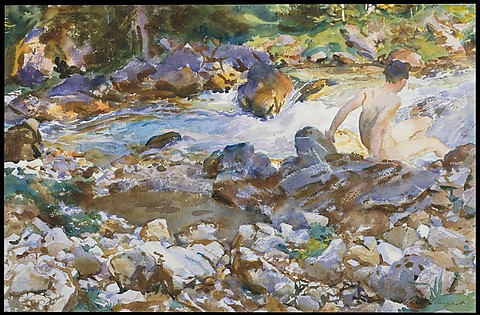

When using a dry brush on a textured sheet, the watercolor will only skim the surface of the paper and not penetrate the hollows, allowing the white of the paper, or an underlying color, to show through.

A watercolor drawing may be modified by partially or fully removing pigment from a composition to reveal the underlying white paper. Blotting with cloth, soft paper, or a sponge can be used to lift watercolor while still wet, as well as to apply it. Other techniques that will remove color include scraping with the end of a brush handle or a knife after the watercolor has dried. To block out or define motifs, artists can mask areas with wax or tape.

Both the use of a dry brush and reductive techniques can create the effect of flickering light by exposing selected areas of the underlying white sheet. For instance, in the drawing below, scraping allowed J. M. W. Turner to create highlights that dramatize the subtle layers of wet and dry effects.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (British, 1775–1851). The Lake of Zug (detail), 1843. Watercolor over graphite, 11 3/4 x 18 3/8 in. (29.8 x 46.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marquand Fund, 1959 (59.120)

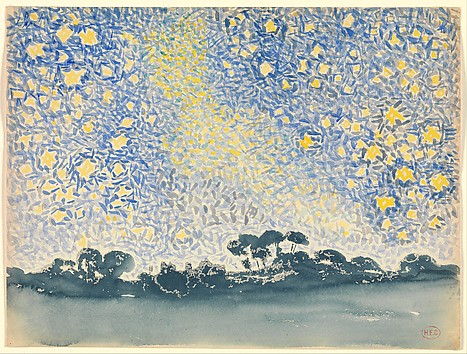

Layered washes of different hues and densities will modify colors, while additives—mixed in or applied above the paint layer—produce a range of effects. Gum tragacanth, for example, thickens watercolor strokes to resemble oil paint, gum arabic creates lustrous surfaces, and drops of alcohol or salt result in textural effects. Watercolor is often combined with gouache (also known as bodycolor, or opaque watercolor), a medium that contains a higher ratio of pigment to binder than pure watercolor. Thickened gouache has a tactile appearance and artists often use touches of it to highlight watercolor compositions. In the detail below, Eugène Delacroix added gum arabic to saturate his colors and gouache to suggest light reflecting off metal armor.

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Goetz von Berlichingen Being Dressed in Armor by His Page George (detail), 1826–27. Watercolor and bodycolor with gum arabic on wove paper, 8 3/8 x 5 5/8 in. (21.3 x 14.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Thomas P. Campbell, 2014 (2014.732.2)

When used to create an entire composition, gouache is distinguished by its lack of translucency and the subtle light reflections from its matte surface, as seen in the chalky white passages in Barret's group of trees.

George Barret, the elder (Irish, 1732?–1784). A Mother and Children Resting beneath a Large Beech Tree, Deer Grazing Beyond, possibly in Norbury Park, Surrey (detail), 1776. Graphite and body color with gum arabic, 19 5/16 x 20 1/4 in. (49 x 51.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Guy Wildenstein Gift, 2012 (2012.46)

In the sixteenth century, opaque and transparent watercolor was used for portrait miniatures, detailed renderings of the natural world (such as Hans Hoffman's study of grasses below), decorative drawings, and maps. It was only at the end of the eighteenth century that water-based media achieved widespread popularity for landscape and genre scenes. In the nineteenth century, such materials were used to create large-scale exhibition drawings, exemplified by Alfred William Hunt's mountain view. Societies devoted to elevating watercolor's status were established to promote its diversity and encourage popularity among professional artists and amateurs.

Left: Hans Hoffman (German, ca. 1545/1550–1592/1592). A Small Piece of Turf (detail), 1584. Brush with gouache and watercolor over traces of charcoal underdrawing, 8 7/16 x 12 13/16 in. (21.5 x 32.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997 (1997.20). Right: Alfred William Hunt (British, 1830–1896). Snowdon, after an April Hailstorm [or Snowdon through Clearing Clouds] (detail), ca. 1857. Watercolor, 13 3/8 x 19 11/16 in. (34 x 50 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harry G. Sperling Fund, 2016 (2016.597)

Marquee image: Richard Parkes Bonington (British, 1802–1828). View of Rouen from St. Catherine’s Hill (detail), 1821–22). Brush and watercolor and pen and brown ink over graphite, 5 13/16 x 9 1/16 in. (14.8 x 23 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, David T. Schiff Gift, Harry G. Sperling Fund, and Karen B. Cohen Fund, 1996 (1996.277)