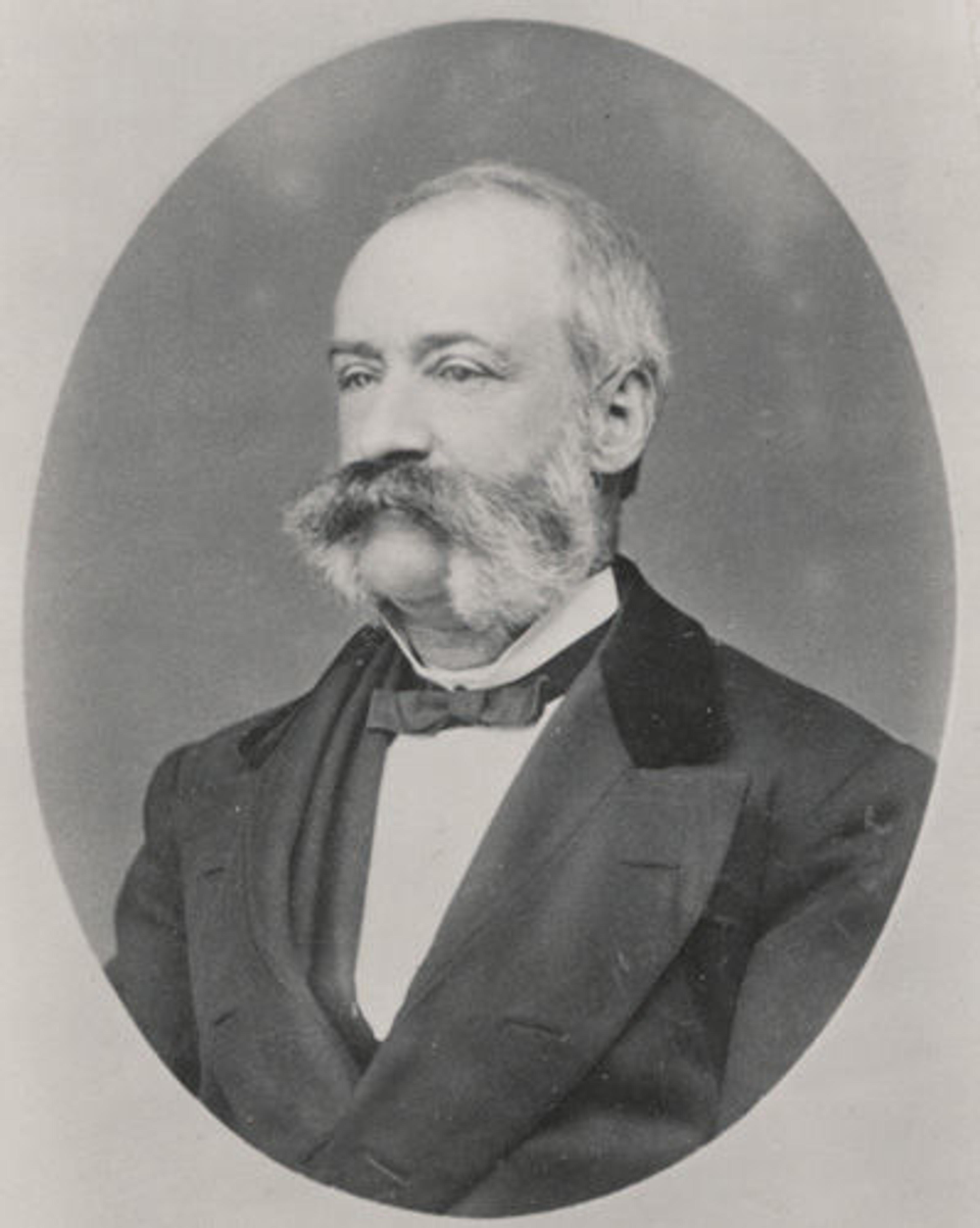

Jacob S. Rogers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

«One hundred and ten years ago this weekend, on July 2, 1901, American locomotive magnate and Metropolitan Museum of Art benefactor Jacob S. Rogers died. Unbeknownst to the Museum's staff and Trustees at the time, Rogers's death would result in the largest and most significant financial contribution to the institution until that time, and among the most important in its history.»

Considered during his lifetime to be a miser and misanthrope, Rogers was known for his tightfistedness and shrewd business practices. As president of Rogers Locomotive Works in Paterson, New Jersey, he owned and frugally managed the company for nearly fifty years. His obituary, published in the Paterson Guardian, described the town's wealthiest citizen—a lifelong bachelor—as "a pure animal man, with no sentiments born of human love or human sympathy." Furthermore, one of the few men who ever gained the slightest entry into Rogers's confidence confessed that his "character was anything but loveable."

According to Calvin Tomkins in his book Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers came across a newspaper article in the late 1870s or early 1880s about an affluent Chicago man who excluded his family from his will and left his entire estate to educational institutions. Though the family contested the will, it was ultimately upheld. Interested, Rogers requested and received a copy of the man's will and made the first of several peculiar annual visits to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1883, Rogers became a member of the Metropolitan, subsequently returning each year to submit a $10 check—always hand-delivered to the Museum's first director, Luigi Palma di Cesnola—to cover his Membership dues. After 1891, his visits became more frequent. In 1901, Cesnola commented that Rogers

seemed desirous to become fully acquainted with every detail of the administration of the Museum. He asked many questions concerning the financial resources of the Museum, the annual cost of operating it, how much the city appropriated for its maintenance, and how much the Trustees contributed towards these and other expenses, what endowment funds we had, etc.[1]

Cesnola recalled that Rogers was particularly interested in whether Trustees such as Henry G. Marquand, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Darius Ogden Mills, and W. E. Dodge were actively involved in the running of the Museum, and that he was pleased to learn that they were. Rogers's visits to the Museum seemed solely informational in nature—he cared little for art and owned no art objects of any value himself—and Cesnola admitted that he could not comment on whether Rogers had ever entered the Museum's galleries. On one of his visits to the Metropolitan, Rogers offhandedly mentioned to Cesnola that he intended to "remember" the Museum in his will; however, the director thought nothing of it, as many Members often left one or two thousand dollars to the Museum in their wills. After 1899, Cesnola never saw Rogers again.

In 1901, the year of Rogers's death, the Museum learned of the bequest from the newspapers. Cesnola admitted that up until that moment he did not even know that Rogers was wealthy. Rogers's will outlined that several small bequests were to be made to his surviving nephews, yet The Metropolitan Museum of Art was to be made the residuary legatee of his entire estate; he left explicit instructions to liquidate assets in order to establish an endowment fund for the Museum. The Metropolitan's share of Rogers's estate came to approximately $5 million, in addition to over $1 million worth of real estate, making this the institution's first bequest of over $1 million. In 2011 dollars, the buying power of the funds equals over $170 million. According to Cesnola, Rogers's bequest was particularly unusual because New York millionaires rarely established endowment funds for institutions: "They will give money for buying collections, and for building purposes, because both remain visible monuments of their generosity . . . while endowment funds are invisible and remain unknown to the general public."[2]

As Rogers stated in his will, the Museum was forbidden to touch the principal sum of his endowment; the institution could spend only the income generated by the bequest. The will read:

The income only of the fund hereby created, or intended so to be, to be used for the purchase of rare and desirable art objects, and in the purchase of books for the Library of said Museum, and for such purposes exclusively, the principal of said fund is not to be used, diminished or impaired for any purpose whatever.[3]

By 1904, only one year after the settlement of the will, the endowment fund yielded over $200,000 to the Museum. For more than a century, the accumulated interest of the Rogers Fund has been used to purchase thousands of art objects, and it continues to fund significant acquisitions to this day.

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). A View near Tivoli (Morning), 1832. Oil on canvas; 14 3/4 x 23 1/8 in. (37.5 x 58.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.27)

The January 23, 1903, purchase of Thomas Cole's A View near Tivoli (Morning) was the first acquisition made with money from the Rogers Fund.[4] The Museum bought the painting at auction from the estate of Henry Gurdon Marquand, an early Trustee of the Museum and its second president. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives has undertaken a project to digitize a selection of Marquand's personal papers that focus on his activities as an art collector and benefactor to the Museum.)

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, ca. 50–40 B.C. Roman, Republican. Fresco; Room: 8 ft. 8 1/2 in. x 10 ft. 11 1/2 in. x 19 ft. 7 1/8 in. (265.4 x 334 x 583.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.13a–g)

Among other remarkable objects the Rogers Fund brought to the Museum are Egyptian works such as the tomb chapel of Raemkai, a collection of funerary models from the tomb of Meketre (examples include a model granary and funeral boat), the jewelry and jewelry chest of the princess Sithathoryunet, and a number of large statues of Queen Hatshepsut (see example). Other noteworthy Rogers Fund purchases include the nineteen frescoes from the Pompeian villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, as well as an Etruscan bronze chariot dating from the sixth century b.c. The most recent acquisition made possible by the Rogers Fund was the Museum's 2011 purchase of a sixteenth-century wool and silk tapestry by Perino del Vaga titled Neptune from the "Doria Grotesques."

The parsimonious Rogers once boasted, "If I could convert all my possessions into paper and provide that this paper should be burned after my death I should do so." Yet Rogers ultimately presented that paper to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, thereby bringing this young, yet industrious, institution to the forefront of the international art world. As one of Rogers's only confidants once said, "His principal aim in life was to do something wholly unexpected of him." He certainly succeeded.

Jonathan Bloom is an intern in the Museum Archives.

Notes

[1] Statement of the Director of the Museum in RE. Rogers, July 15, 1901. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

[2] Calvin Tomkins, Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: H. Holt, 1989).

[3] Copy of Jacob S. Rogers's Last Will, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

[4] "Metropolitan Museum Reports Prosperity," New York Times, April 3, 1904.