To commemorate Black History Month, fashion historian Jonathan Square commissioned several essays on Black designers currently featured in the special exhibition In America: A Lexicon of Fashion. You can read the introductory essay here.

The account of how Daniel Day became Dapper Dan is both extraordinary and a familiar American origin story of self-determination. In his recently published memoir, Dapper Dan: Made in Harlem (2019), Day may raise some eyebrows by describing his background candidly as a criminal and a hustler. However, it is a story not unlike many others. Dig a little and you will find America’s version of aristocracy is built on a foundation of enslavers, bootleggers, and gangsters. Over time, Dapper Dan parlayed his business acumen and shrewd survival skills into legitimate work. With his haberdashery, he found a niche uptown with an underserved clientele who wanted access to luxury goods. His Harlem storefront, Dapper Dan’s Boutique, opened in 1982.

Dapper Dan of Harlem (American, founded 1982), designed by Daniel Day (American, born 1944). Coat, 1988. Leather. Courtesy of Dapper Dan of Harlem

In interviews and in his book, Dapper Dan discusses his views on the business side of fashion with startling pragmatism. He seems to possess an unassuming, even avuncular disposition. His expressiveness, of course, is ultimately found in his dress. He cuts a tall figure in his trademark bespoke suits, always tailored within an inch of their lives, and styled with an over-the-top accessory or three: matching frames, an ascot, cufflinks, a boutonnière, and impeccable shoes. In his personal presentation, Dapper Dan emanates what professor Monica Miller calls the “semiotic power of the dandy.” He is the flaneur with a swagger beyond reproach, a Harlem dandy.

Dapper Dan was born in Harlem in 1944, just after the peak of the Harlem Renaissance but before crack and the AIDS crises ravaged historically Black neighborhoods across the country. He was, therefore, intimately aware of Harlem’s glorious past. Today, his atelier stands as the lone emblem of the neighborhood’s history of sartorial splendor—a rich legacy that hearkens back to the work of preeminent photographer James Van Der Zee (1886–1983), who documented the Black bourgeoisie and celebrities of Harlem from the late nineteenth through the twentieth centuries in opulent environments carefully constructed in his studio. The wedding and society portraits of these beautifully self-styled men and women in tea gowns and tuxedos reflect our collective memory of the era.

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886–1983). Identical Twins, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 18.7 x 23.8 cm (7 3/8 x 9 3/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James Van DerZee Institute, 1970 (1970.539.2) © James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

For the most part, those first Black habitués of Harlem did not purchase garments outside of the neighborhood. The average household likely had their clothes made at home or by a local seamstress or tailor. Indeed, it was not uncommon for Black women to be skilled dressmakers. From the antebellum period through World War II, these women often made clothes for the families they worked for and their own. While there are a few exceptions—like Elizabeth Keckley, Harriet Jacobs, and Ann Lowe—for the most part, these women are the hidden figures of American fashion history and the evolution of the Black style. When several commercially successful Black male designers emerged in the 1970s seemingly all at once, many of them, including Willi Smith, Patrick Kelly, and Stephen Burrows credited their mothers and grandmothers for their love of fashion and knowledge of construction and materials. Dapper Dan writes in his memoir that his own mother, an artist who drew fashion illustrations, was a major influence.

Growing up in Philadelphia in the 1980s and ’90s, I cannot say I knew who Dapper Dan was, though I was certainly obsessed with fashion. At age seven or eight, an auntie in my family taught me how to sew and crochet clothes for my Barbies. I consumed fashion magazines and films that showcased clothes like Essence magazine and the 1995 documentary Unzipped. Eventually, I discovered the significance of Harlem in school and grew mesmerized with the art and glamour associated with this Black enclave of creative genius.

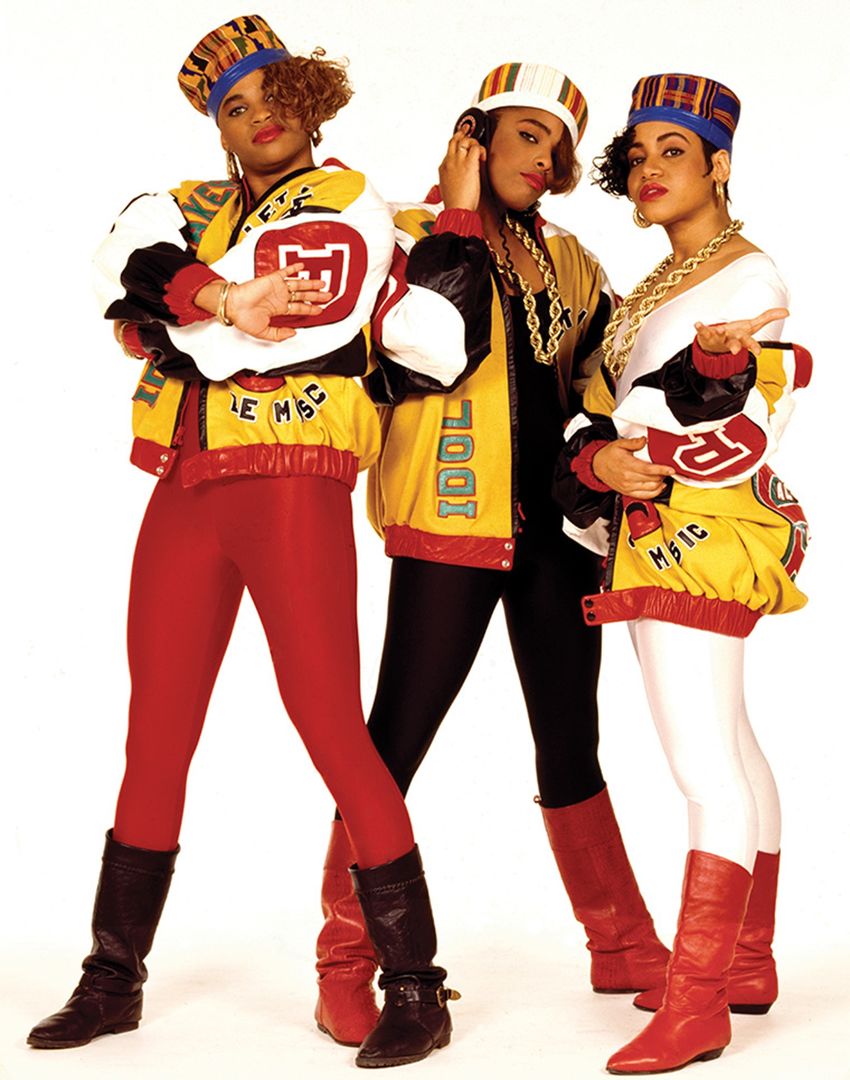

There are two iconic images that I still return to often. The first is Salt-n-Pepa’s album cover for Push It (1987). This image is a manifesto. Dapper Dan, who often worked closely with his clients on commissioned garments, designed this jacket in collaboration with Christopher Martin, who worked with Salt-n-Pepa at the time. Dapper Dan is primarily known for his appropriation of fashion house logos, who took recognizable symbols and tailored them to a Black aesthetic—a technique that hip-hop artists were perhaps drawn to because sampling is a prominent element in the genre.

Salt-N-Pepa in their jackets designed by Dapper Dan and Christopher Martin. Photo: Janette Beckman/Redferns/Getty Images

One could argue that Dapper Dan did not invent this aspect of fashion. His genius lies in his ability to see a dearth in the marketplace, apprehend the vernacular of popular taste, and then articulate an aesthetic that already existed. That is Black style. “So goes Harlem; so goes the Black cultural world,” Dapper Dan proclaimed in a 2020 Vogue video. The logos on Salt-n-Pepa’s jackets were actually designed by Dapper Dan with Martin. They have a familiar ’80s silhouette. The styling of the outfits is gendered as these jackets and thick gold chains were more the purview of the male MCs; here, they are paired with form-fitting catsuits. The looks read like a series of juxtapositions, but the jackets are the standout pieces of their ensembles. Salt-n-Pepa’s stance and gaze assert that these are women who are winning in a male-dominated industry.

The second image or group of images that speak to my fascination with Harlem and fashion is related to the first. The artist William Henry Johnson (1901–1970) was born in Florence, South Carolina, and moved to New York City when he was seventeen. There, he trained as an artist whose paintings limn the vitality and imagination in Harlem that fostered so much creativity. To my eye, the Salt-n-Pepa cover is descended from Johnson’s Jitterbugs series (ca. 1941). There is a formal relationship between the images—palette, composition—and there is also an energy and pride evident in both. Salt-n-Pepa accessorized their looks with Kente-cloth-inspired hats that point to an emerging consciousness around the African diaspora, not unlike a similar movement during the Harlem Renaissance.

Left: William Henry Johnson (American, 1901–70), Jitterbugs (I), ca. 1940–41. Oil on plywood, 39 ¾ x 31 ¼ in. (101 x 79.4 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation (1967.59.590). Right: William Henry Johnson (American, 1901–70), Jitterbugs (II), ca. 1941. Oil on paperboard, 24 x 15 3/8 in. (61 x 39.1 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation (1967.59.611)

This pride can also be seen in the now-infamous portrait of Diane Dixon modeling another design by Dapper Dan from 1989. The photograph surfaced as a document of Dapper Dan’s innovation when he relaunched his brand in 2017. Dixon is proudly posed in front of a printed reproduction of sixteenth-century Benin sculpture. In many ways, the Harlem Renaissance and the emergence of hip-hop can be characterized as very similar movements of contemporary Black expression through activism, cultural pride, and innovation in both music and fashion.

The model Diane Dixon in 1989, wearing Dapper Dan. Courtesy Dapper Dan of Harlem

I moved to New York as a university student in 2004. I feel proud and lucky to say I have lived and worked in Harlem for the better part of a decade, a place I consider hallowed ground. On occasion, as I make my way along the boulevard, I catch sight of Dapper Dan and am blinded by his beautiful attire as he stands by the stoop of his brownstone, keenly watching passersby. His atelier is across the street from the site of James Van Der Zee’s famous Lenox Avenue studio. He is a designer poised at the nexus of Black style and creativity, who embodies the brilliance of Harlem both old and new.