SPEAKER 1: Music in Harlem is an expression. That’s what music in Harlem was. You go all the way back to what they call the “Slop Jar Blues,” the different types of blues.

SPEAKER 2: Busy, sweet, bustling, cultural. Noisy but beautiful. Eccentric, different.

SPEAKER 3: Sounds like my backyard and my neighbor’s backyard and it sounds like friends arguing.

SPEAKER 4: R&B, jazz. That’s mainly... R&B and jazz. You got to Brooklyn is kind of more like a Jamaican type, you know, more calypso, but Harlem is more like soul and jazz and R&B.

JESSICA LYNNE: Welcome to Harlem Is Everywhere, brought to you by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’m your host, Jessica Lynne. I’m a writer and art critic. This is episode four: Music and Nightlife.

The music of the Harlem Renaissance encapsulated the spirit of a time and place. Think of this episode as a crash course on just a few of the hundreds of talented musicians from this time. And even though this era was known as the “Jazz Age,” we’ll reflect on how painters and writers were involved in the conversation, too.

The big ballrooms and fancy clubs were obvious attractions but there were also dives and hole-in-the-wall joints for those in the know. There were also pool halls and back-room gambling spots where patrons could test their luck and take a risk. And nightclubs where people could explore and challenge mainstream cultural ideas around sexuality and what society deemed acceptable.

We’ll hear from art historian and professor James Smalls:

JAMES SMALLS: It’s human nature. When you tell people they can’t do something, that’s when they want to do it! They’re asking, “Well, why can’t I?”

LYNNE: Additionally, we’ll hear from scholar and curator Richard J. Powell.

RICHARD J. POWELL: The aura of the sounds and the energy of the music really enraptured people.

LYNNE: And Grammy Award–winning musician and composer Christian McBride:

CHRISTIAN McBRIDE: It must have been a period of discovery where everyone felt no bounds. They didn’t feel any pressure to recreate something that had been done.

—

LYNNE: Picture this: it’s May 1926 and the streets of Harlem have been buzzing—actually no, shouting—about a club that’s bringing a bit of glamor and mystery to uptown nightlife. Everyone’s swinging at this new spot and you aren’t going to be the only person in Harlem missing out.

At least, this is what you think to yourself as you hand your coat over to the attendant. You’re smiling a little too hard and he’s smiling back at you with a knowing look in his eyes.

You make your way back up two flights of marble stairs where your friend and a sprawling dance floor are waiting for you. Here it is: the Savoy Ballroom.

It’d almost be too overwhelming if it weren’t so spectacular. There’s hardly an empty spot on the floor, even on a Sunday! So this is why all of Harlem is racing up Lenox Avenue.

As the band plays on, you find a corner perch and stare out at the couples who are already moving their bodies in ways you can only aspire to. You watch, mesmerized, as they defy gravity with their twists and turns and leaps, their feet barely touching the ground. How do they do that?

You keep tapping the side of your left thigh to the house band’s rhythms. Chuckling a little at your friend who has found her partner already, her forehead gleaming with sweat. You’re thankful because between the two of you, you’re definitely the shyer one. and since she’s occupied, she can’t tease you for being a wallflower. And so what if you are?

You just love being out, consumed by the music and momentum of it all. That energy that feels distinctly Harlem.

So, you push a few curls out of your face and stare down at the sequins of your blue dress. You hear a throat clear and you look up to find a pair of brown eyes staring at you, and a hand outstretched. You decide to accept this unspoken invitation.

There’s an entire night waiting for you.

—

LYNNE: It’s hard to conjure ideas and images of the Harlem Renaissance without thinking of music.

Today, jazz is recognized as an American art form. Its influence has spread around the world. Its sound and style has evolved with generations of musicians. The Harlem Renaissance was a time when this musical art form jumped on to the American stage and declared its presence.

Here’s bassist, composer, and arranger Christian McBride:

McBRIDE: Ironically, in America, the most respected composers were European composers: Bach, Beethoven, Mozart. Those were the people that mainstream American culture viewed as the highest order of artistry.

LYNNE: That was about to change with the arrival of Edward Kennedy Ellington, also known as “Duke.”

McBRIDE: And it was Duke Ellington who was able to make America know that we have our own Mozart. We have our own Beethoven. Being one of the first, not just African American, but of any descent, to be able to write like he did, where you were able to somehow get the feeling of the street. You could get the feeling of the Harlem dance club, but also put in what we learned from extended composition from the European composers and somehow balance that into this new voice.

LYNNE: These musicians were building new sounds and approaches. Like other artists from the Harlem Renaissance they were claiming this time as their own.

McBRIDE: I think that these musicians that we talk about, not just their style, their cool nicknames, but their incredible talent. You know, someone like Willie “The Lion” Smith, who was able to get the feeling of an entire band with just a piano, just his ten fingers on a piano. The way Louis Armstrong could create modern-day improvisation to the point where people could listen to him play and say, you know, we’ve never heard anyone do that before. Do you mean you’re making that up?

LYNNE: Musicians were changing their sound and the way they would perform.

POWELL: There were entertainers during that time period who exuded a different kind of vibe.

LYNNE: Scholar and curator Richard J. Powell.

POWELL: Bessie Smith was really a kind of down-to-earth, raunchy kind of gutbucket entertainer. Ethel Waters, on the other hand, knew that world from her early years as a vaudevillian. But by the late twenties, early thirties, she has kind of graduated to Broadway. And so her music has elements of the folk, but it’s so much more distilled and is so much more elegant in the way she even pronunciates.

Carl Van Vechten (American, 1880– 1964). Bessie Smith Holding Feathers, 1936. Gelatin silver print, 13 1/4 x 10 7/8 in. (35.3 x 27.8 cm). Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

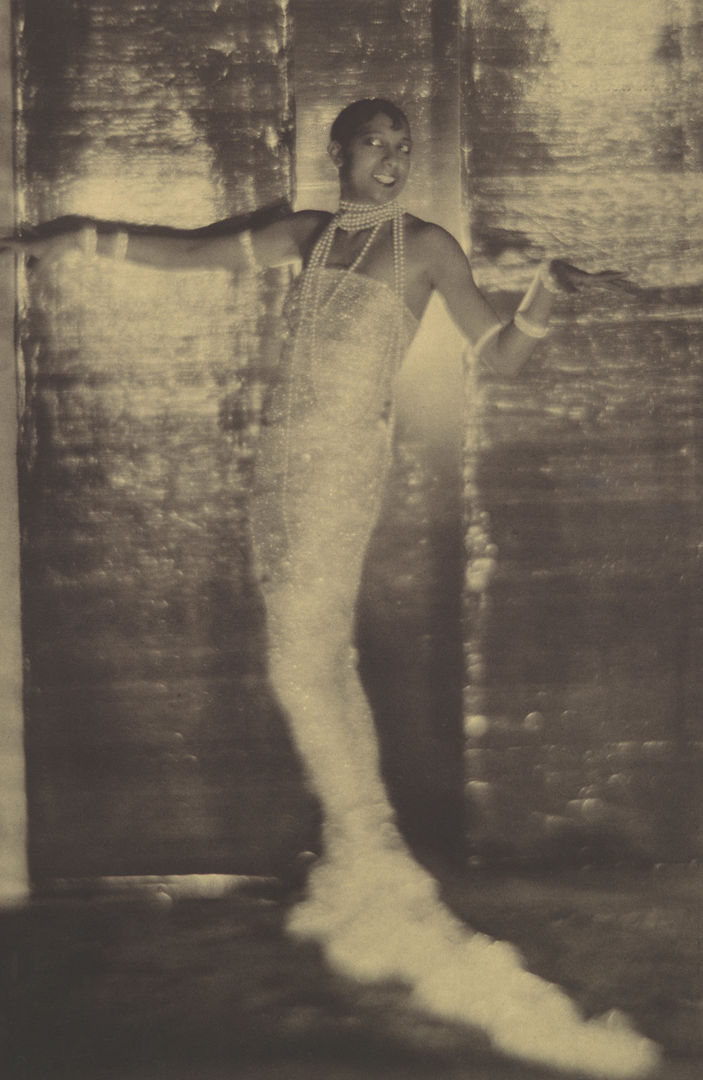

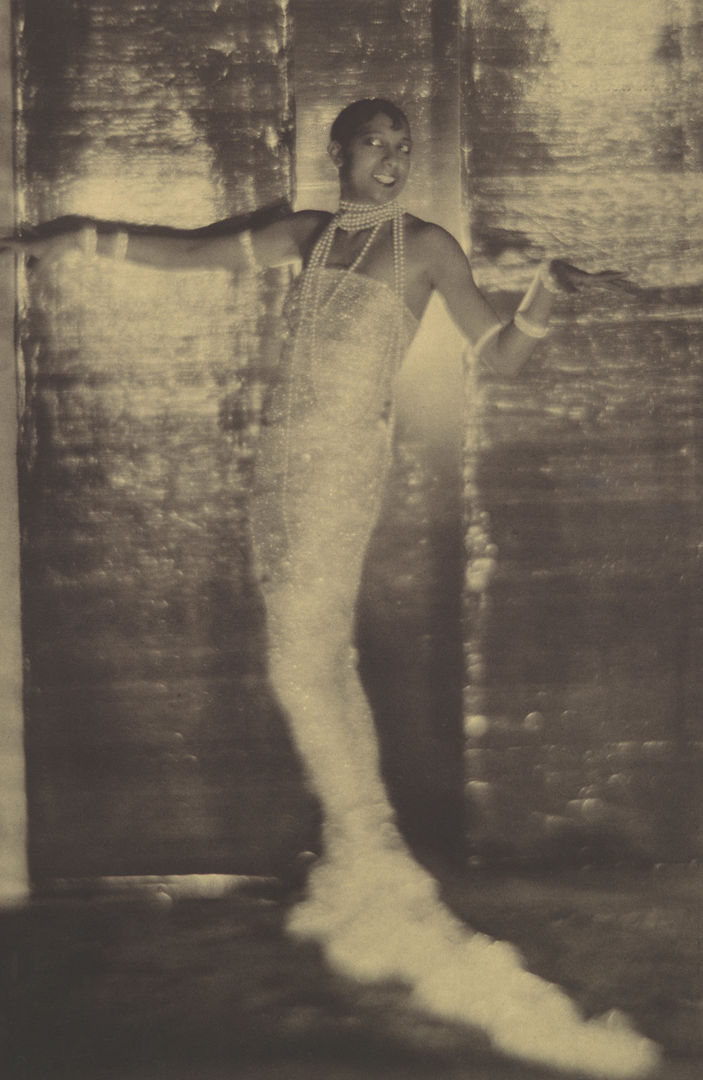

LYNNE: Like the writers and visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance, these performers and musicians were in conversation with audiences beyond Harlem and America. One example is Josephine Baker.

POWELL: Who jumps ship, meaning she leaves America and creates a whole new identity of this incredible, beautiful chanteuse, who sings in French and who dances these incredible suggestive dances and literally becomes an icon. So much so that I have to say that when she comes back to the United States, they can’t handle her because they’ve never seen anything like this beautiful, gorgeous brown woman performing, speaking French.

Adolf de Meyer (American, born France, 1868–1946). Josephine Baker, 1925–26. Direct carbon print, 17 7/8 x 11 5/8 in. (45.2 x 29.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.16)

LYNNE: European audiences couldn’t get enough of a performer like Josephine Baker. Her voice and dance moves set the continent ablaze. The jazz music brought across the Atlantic by performers and American soldiers was an instant phenomenon.

Many Europeans’ first exposure to this uniquely American style of music was through bands attached to the army. Specifically, the 369th Infantry Regiment led by James Reese Europe…

MURRELL: Who before he served in the army, had been a distinguished composer songwriter in New York and had established a career as a conductor.

Unknown artist, Lieutenant James Reese Europe Conducting in Paris, 1919. Gelatin silver print, 8 3/4 x 7 1/2 in. (22.2 x 19.1 cm), Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

LYNNE: That’s Denise Murrell, curator of The Met’s exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.

MURRELL: So, they were performing jazz concerts for the troops, American troops, but also British, French, the Allied troops. And many scholars credit the James Reese Europe Band of the Harlem Hellfighters with introducing jazz to Europe.

LYNNE: The idea of seeing this music live was irresistible. Harlem in turn, especially in the 1920s and thirties became a playground for elites.

POWELL: The White elites, in particular. Also people from around the world, people from France, people from Germany, people from Spain, people from the UK during the twenties and thirties come to Harlem because they’ve been told it's a great place to listen to music. It's a great place to watch Black people be art personified.

LYNNE: Like moths to a flame people from all over Manhattan and the world flocked to the lights of the marquees. Grand venues like the Savoy Ballroom or the Cotton Club were filled with people moving to the music. They danced the foxtrot, the Charleston, and threw each other around with the Lindy Hop.

Here’s Christian McBride again:

McBRIDE: The idea of kind of sitting down and listening to extended improvisational jazz, that wasn't really quite the case, at that time.

LYNNE: It was all about dancing.

White people from downtown wanted to experience what was happening in Harlem but not necessarily side by side with Black people. It was fine to have Black artists perform for them but not to share a dance floor. They wanted our rhythm but not our blues.

Here’s art historian James Smalls:

SMALLS: Well the club venues, I believe were a little bit more commercialized. And also, I mean, segregation was very much so in evidence. Places such as the Cotton Club, of course African Americans were not allowed in, but they were as entertainers.

LYNNE: Lenox Avenue and Seventh Avenue and all the streets in between were packed with places to see the bands of the day. Places like Connie’s Inn, the Radium Club, the Lafayette Theatre, or Smalls Paradise. It all happened here in just three square miles.

If you wanted to go dance the Lindy Hop in a nonsegregated spot you’d head to the Savoy Ballroom.

The Cotton Club was a good place to catch Duke Ellington’s orchestra—if you were White, that is.

Connie’s Inn was another segregated hot spot that was popular at the time. Its Art Deco design and star-studded list of performers attracted crowds from all over.

Not all of the legit clubs were available to people who actually lived in Harlem, but that didn’t mean there weren’t other options.

SMALLS: And then in the other places, the smaller places or the more underground places, of course, you had people who went to those places in order to engage in all sorts of things: drinking, and sex, and drugs, and those kinds of things. But also to experience the music, as well.

Harlem became this destination for this kind of escape, kind of bucking the dictates of society. In other words, to be modern.

LYNNE: After all, this was a Renaissance. A rebirth. Not only for artists and intellectuals but for all Black people. A time to reshape the national narrative around Blackness. Some of this reshaping came in the form of pushing boundaries. Boundaries concerned with sexuality and public norms.

SMALLS: You would walk in and there could be somebody at the door. The place I would think would be dark. And if there’s music playing jazz or whatever, then it would be dark and smoke-filled cause everyone would be smoking, and drinking also. And then there might be spaces, where say women are gathering. They’re socializing, they’re enjoying each other’s company. You’d have people who are men who are dressed as women or women dressed as men—this kind of cross-dressing phenomenon that was actually the case, we know, in the Savoy Ballroom, for example, and in the Hamilton Lodge.

Maybe if the place was large enough, you’d have some sort of entertainment. Someone could be singing, or dancing, or performing some sort of act.

LYNNE: Gladys Bentley was a popular performer of the time. She took to the stage in a tuxedo, top hat, and tails performing as an openly queer woman. Her lyrics were considered risqué and she flirted with the women in the crowd.

Historian and professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. described the Harlem Renaissance as quote “surely as gay as it was Black.”

There’s a photograph from the mid-1920s by James Van Der Zee titled [Person in a Fur-Trimmed Ensemble] previously known as Beau of the Ball.

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886–1983). [Person in Fur-Trimmed Ensemble], 1926. Gelatin silver print (printed later), 9 3/4 x 7 3/8 in. (24.8 x 18.8 cm). James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Donna Van Der Zee, 2021 (2021.446.25)

SMALLS: It represents a cross-dresser, one of the many cross-dressers that would have been seen at a place such as the Hamilton Lodge where drag balls took place, which were quite popular in Harlem, particularly during the thirties.

Here the individual is shown wearing a dress that she probably made herself and sort of displaying that. So, this really makes reference to the phenomena of the drag balls and cross-dressing as a mode of excitement and liberation in Harlem during this period.

They were quite popular affairs covered in the press. And in fact, Langston Hughes wrote about these kind of events in his autobiography called The Big Sea, and he described these kind of drag balls as “spectacles in color.”

—

LYNNE: The clubs and ballrooms were obviously exploding in popularity, which also means they were expensive. Many residents of Harlem couldn’t afford to spend the money on an extravagant night out. Some people even had trouble paying rent. In these cases, folks would throw rent parties.

These were house parties where the hosts would invite their friends and a few musicians, cook up some food, and at some point pass around the hat to help with the monthly rent.

Here’s Christian McBride again:

McBRIDE: You know, a lot of those Harlem rent parties is where the Harlem piano style really flourished.

LYNNE: These parties were places musicians could come to after a gig and meet up with friends, have a home-cooked meal, and play some more. Many of these apartments had pianos and you would certainly hear some Harlem stride—the signature piano style of the Harlem Renaissance.

McBRIDE: The Harlem stride piano style. And this was made popular by people like Willie “The Lion” Smith, Albert Ammons, Luckey Roberts, and players and composers like James P. Johnson.

When you hear those great piano players of those early days, it literally was a full orchestra. You know, the left hand playing what was basically like a rhythm guitar part and a drum part. You had the right hand playing the melody and punctuating the chords. That style of piano playing, it really takes some serious, dedicated practice to get that together. And every piano player from that period played like that.

LYNNE: A singular master of stride piano was the larger than life character Thomas “Fats” Waller.

McBRIDE: If you listen to Fats Waller’s music today, it’s safe to say he was kind of like the first Snoop Dogg, you know, because he would write music about weed. He would write music about partying. But I think because of the humor of his music, his mastery of the piano got obscured. Shortly after the Harlem Renaissance, Art Tatum came along. It just… he was an alien. He took all of that stride piano playing from the Harlem Renaissance and just took it to the next level, if you could possibly believe that.

—

LYNNE: The bands, and the music, and the party, and nightlife paint a picture of a time bursting with beauty and contradiction.

But not everyone is drawn to the dance floor. Remember, the 1920s was a time of prohibition. Alcohol was illegal, which resulted in a lot of speakeasies and back-room bars. These dark and private locations were also filled with card games and pool halls.

POWELL: This is not something that’s happening for the world to see. And so you have this phenomenon of speakeasies, these places where people knew through word-of-mouth that there was something going on there that might involve gambling, that might involve liquor, that might involve listening to great jazz and blues music.

LYNNE: That’s scholar and curator Richard J. Powell again.

POWELL: People knew about these places through word-of-mouth. They often were places that didn’t open until late, late at night. And we’ve all seen these in the old movies where you tap on the door and you say, “Joe sent me,” and then you enter these spaces.

The exteriors look like normal, everyday neighborhoods. But when you knock on the door and you’re led in, you see other people, you see tables set up with liquor. And you see people sometimes dressed up in really amazing outfits. This was a moment where people really kind of had fun with their fashion—zoot suits, and dresses with fringes on them, and feathers, if you were inclined that way.

LYNNE: An important painting that reflects this kind of scene is Jacob Lawrence’s Pool Parlor, made when the artist was in his twenties.

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). Pool Parlor, 1942. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 31 1/8 x 22 7/8 in. (79.1 x 58.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1942 (42.167)

POWELL: Where we see these men, with their sticks and the balls and those beautiful viridian green felt tables. You know, on one hand, you're in a pool hall, in another way, you’re in the cosmos. Where you’re in this world of green and you have these stars that are actually balls that you’re playing pool with, and then those wonderful lights hanging over the tables. So, he’s transformed something that is quite quotidian and very urban into something very mystical and spiritual.

LYNNE: These late night after hour spots caught Powell’s interest not just as places full of story and drama and culture. They’re also places full of emotion.

POWELL: The kind of psychological dynamics of play and leisure and how it’s really a larger meditation on life. The risk that people take, the chances that people take, the bluffs, the illusions that people present to one another. Whether it’s for a game of cards or whether it’s in relationships or whether it’s the workaday world.

LYNNE: Underground economies offered a chance to make some quick money—but, at the same time, they also represented the real risk of losing it.

POWELL: I mean, we call them games but people wanted to make money. People wanted to succeed and win a hand. It was also risky because you might lose all the money that you thought you were going to hold onto or earn. So, money that you need for rent, money that you need to pay for your family to eat might disappear, in a couple of hands of cards. And that was devastating. And so there’s real high drama in all of this.

LYNNE: The nightlife of this time didn’t just take place inside clubs and pool halls or at house parties. Just walking down the street was exciting enough.

An artist we mentioned in episode two whose work captures this excitement is Archibald J. Motley, Jr.

Born in New Orleans and relocating with his family to Chicago’s South Side as a boy, Motley is a good example of an artist working outside of Harlem who held the New Negro mindset.

Motley’s work was centered around the day-to-day life of Chicago and its people.

POWELL: And he comes into his own in the 1920s with these extraordinary paintings that deal with everyday life in Chicago, people playing cards, people in nightclubs, people in the park hanging out, just with their everyday life, walking up and down the streets. And yet he infuses these works with color. And it’s a color that’s not realistic.

Left: Archibald J. Motley, Jr. (American, 1891–1981). The Liar, 1936. Oil on canvas, 32 x 36 in. (81.3 x 91.4 cm). Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (47.23.P); Right: Archibald J. Motley, Jr. (American, 1891–1981). Picnic, 1934. Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 in. (76.2 x 91.4 cm). Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (47.22.P)

POWELL: It’s not the dull, gray colors of nature. It’s these super-real purples, and reds, and oranges, and lavenders. They’re works that are really infused with the moment with the esprit de corps of Black Chicago.

LYNNE: The music of this time like the movement itself wasn’t a monolith. Alongside all the swinging and fanfare of the big bands and ballrooms was the blues. To Powell it’s not just musical: it’s an aesthetic sensibility.

POWELL: I think about it in terms of the rhythms and the call and response. That’s a part of it. Most classic blues have the A-A-B format where you have two lines that you repeat, and then the third line is kind of the resolution.

LYNNE: Here’s Bessie Smith singing Back Water Blues to show us what Richard Powell is talking about. Notice the lines that repeat and the last line that furthers the story she’s telling us…

[Bessie Smith singing Back Water Blues]

POWELL: When I think about that, I’m not really trying to literally translate that to the visual arts or to literature. I’m really thinking about the idea of rhythm and I’m thinking about call and response, how patterns work best. Not when they are unrelenting, but when they repeat and then they have a counterpoint that goes against them.

LYNNE: This sensibility seemed to stretch across genres, as well. Not only musicians, but visual artists and writers all seemed to draw from this call-and-response and rhythmic approach.

POWELL: And one can think about that in relationship to images, how patterns are often used by painters. And we can think about that in terms of poetry, in terms of sound and repetition, of sound and sound and counter sound. We can even think about that in terms of instrumentation. You know, how pianos, and banjos, and guitars, and all sorts of musical instruments can invoke the human voice and can play with pattern and energy.

LYNNE: The music and nightlife of the Harlem Renaissance was participatory. The musicians needed the audience as much as the audience needed a song. The night clubs and house parties were communities.

Something happens when the sun goes down and street lights turn on. When we’re able to let go of a work week and take a chance on asking someone to dance or play a hand of cards.

It doesn’t always work out the way we might hope—but sometimes, it does.

POWELL: The thing about so much of the culture during this time period is that it wasn’t just about sitting and listening. It was about participating. And so we have artists who almost encourage us to get into the mood, to get into the spirit of what it is that we’re looking at and what it is that we’re thinking about.

As I said, when I talk about the blues aesthetic, I’m also talking about an ethos. I’m talking about how people work their way through a world that is against them because of the color of their skin, because of the class, and the politics, and the socioeconomic realities of that era.

But they find a way out of no way. And finding a way out of no way often means laughing in the face of pain. It means putting on a good face to work your way through the streets. It means, you know, girding yourself for a tough life. Some people don’t make it. That’s the way it goes sometimes. But many people survive and find their way through.

—

LYNNE: We asked Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Carl Phillips to respond to an artwork in the exhibition. In his poem, he touches on some of what Powell is describing as a blues aesthetic. How nights in Harlem were usually exciting, but we can’t forget about the very real threat of violence, too, that lurked in the city and beyond. Especially for those who took risks with their gender expression.

In his response to James Van Der Zee’s photograph [Person in a Fur-Trimmed Ensemble], Carl Phillips imagines what life might have been like for the subject of this portrait. What was on their mind? And what might they have seen when peering out the window?

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886– 1983). [Person in Fur-Trimmed Ensemble], 1926. Gelatin silver print (printed later), 9 3/4 x 7 3/8 in. (24.8 x 18.8 cm). James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Donna Van Der Zee, 2021 (2021.446.25)

LYNNE: Here’s Carl Phillips reading his poem “At the Reception”:

CARL PHILLIPS:

Through the window,

one of those trees I

mainly call manzanita

because that sounds right,

not because I’m sure,

kept finding stillness

then letting go of it

in a small wind. But

inside the window,

the chandelier’s reflection:

so that the tree itself,

for a moment, seemed

chandeliered;

then it looked like

stars, from different

lengths, though, of

invisible rope, being

lynched, but in unison.

—

LYNNE: A big thank you to James Smalls, Rick Powell, and Christian McBride. Also a special thank you to Carl Phillips for sharing his poem “At the Reception.”

In our next and last episode, we explore how the art and culture of the Harlem Renaissance was a form of activism and set the stage for how the next generation of Black America would use their voice.

Harlem Is Everywhere is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with Audacy’s Pineapple Street Studios.

Our senior producer is Stephen Key.

Our producer is Maria Robins-Somerville.

Our editor is Josh Gwynn.

Mixing by our senior engineer, Marina Paiz.

Additional engineering by senior audio engineer Pedro Alvira.

Our assistant engineers are Sharon Bardales and Jade Brooks.

I’m your host, Jessica Lynne.

Fact checking by Maggie Duffy.

Legal services by Kristel Tupja.

Original music by Austin Fisher and Epidemic Sound.

The Met’s production staff includes producer Rachel Smith; managing producer Christopher Alessandrini; and executive producer Sarah Wambold.

This show would not be possible without Denise Murrell, the Merryl F. H. & James S. Tisch Curator at Large and curator for The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism exhibition; and research associate is Tiarra Brown.

Special thanks to Inka Drögemüller, Douglas Hegley, Skyla Choi, Isabella Garces, David Raymond, Ashliy Sabb, Tess Solot-Kehl, Gretchen Scott, and Frank Mondragon.

Asha Saluja and Je-Anne Berry are the Executive Producers at Pineapple Street.

Support for this podcast is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies.