The Artist: For a biography of Gerard David, see

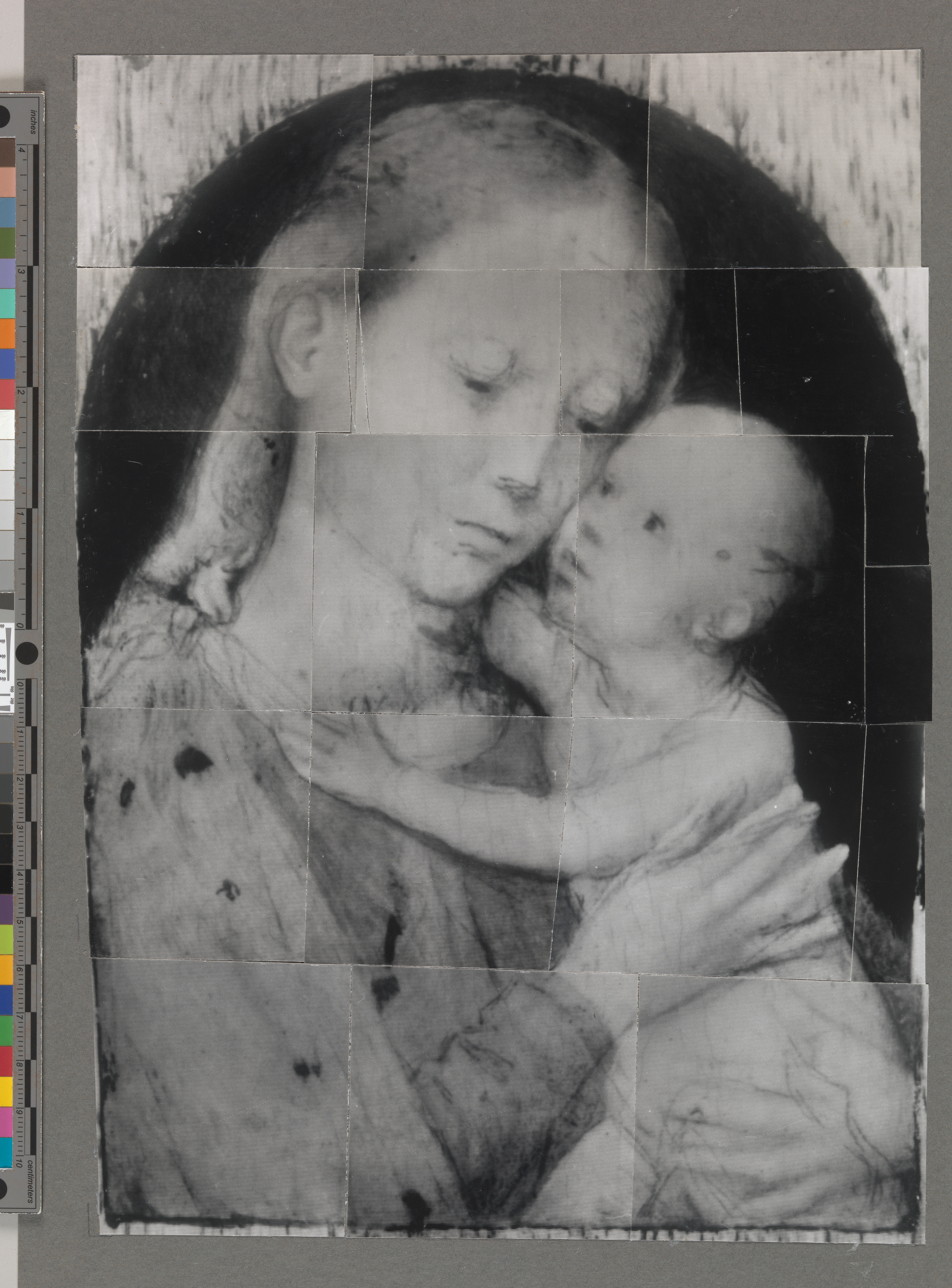

Gerard DavidThe Painting and Its Function: The Virgin and her infant son are shown in a close embrace; Christ wraps his tiny arms around his mother’s neck and presses his cheek close to hers. Set close to the picture plane, the pair are positioned in a manner suggesting a connection between their world and the viewer’s. Although the background now appears grey, this paint is a later addition that covers the original color.[1]

The Virgin and Child motif ultimately derives from Byzantine and Italo-Byzantine prototypes like the

Virgin of Vladimir and the

Cambrai Madonna, thought to have been painted by Saint Luke himself.[2] In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it was common practice to produce painted copies of an image associated with miracles or with attached indulgences like the Cambrai Madonna. These copies were believed to possess the same powers as the original and were therefore highly valued. The Lehman example was likely an adaptation of versions of the Virgin of Tenderness by Rogier van der Weyden and Dieric Bouts (as in

30.95.280, for example).[3]

As Martha Wolff suggested, the painting may have been part of a devotional diptych, similar to those by Gerard David in Munich and Basel, both of which pair the

Virgin and Child with a depiction of a later encounter between Christ and his Mother, such as

Christ Taking Leave of His Mother.[4] The Met’s

Christ Taking Leave of His Mother (

14.40.636) provides a good, if partial, example of the devotional diptych tradition. On the other hand, as Maryan Ainsworth notes, the Lehman Virgin and Child may have functioned as an independent, portable aid for private devotions.[5] In either case, the picture would have been a stimulus to prayer, encouraging an empathic response in its viewer by emphasizing the human connection between Mary and her son and serving as a reminder of Christ’s life on earth.

Attribution and Date: The

Virgin and Child was sold in 1965 as a work from the Flemish school. By the time it entered the Met’s collection, the panel was attributed to Gerard David.[6] The paint surface is severely abraded, particularly in the upper half and the Virgin’s face and hair especially, preventing a thorough analysis of the artist’s technique.[7] However, as evidenced by the painting’s facture in better preserved passages, like Mary’s hand, sleeve and cloak, the work reflects the handling of one of David’s talented workshop assistants.[8] From about 1490 to David’s death in 1523, his Bruges workshop produced paintings for the market and it is to this period that the Lehman

Virgin and Child belongs. In particular, the Virgin’s hands appear somewhat flat, and are rather heavily painted in a manner unlike the technical refinement found in pictures attributed to David.

Further support for an attribution to the David workshop can be found below the paint surface. A loose, sketchy underdrawing executed in a dry medium is present [See Comparative Image, fig. 1] that focuses primarily on the placement of features and establishing contours. David’s underdrawings for other similarly sized paintings features not only lines to establish contour, but also areas of delicate parallel and cross-hatching -

Christ Taking Leave of His Mother (ca. 1490-95, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel) is a good example.[9] Such characteristic hatching is absent from the Lehman underdrawing, suggesting that the hand responsible for this stage was not David himself. This early mapping-out stage reveals the artist’s rough compositional plan, with some adjustments made between the underdrawing and paint application. For instance, the Christ Child appears to have been underdrawn wearing a tunic that was indicated using so few lines that they can barely be made out in the reflectogram. This design was not followed in the paint stages, but its initial presence connects the Lehman composition to other versions by David where the infant Savior is shown wearing a similar garment.[10] Although the presence of searching underdrawn lines suggests a degree of creativity on the part of the artist, the design is likely based on an existing workshop model, drawn or painted, from which the artist derived his initial scheme.

The increasingly streamlined nature of Gerard David’s small-scale workshop production in the sixteenth century provides the backdrop for paintings like the Lehman

Virgin and Child. Its probable reliance on and reproduction of an existing model further recalls the established practice of producing serialized images for the open market towards the end of David’s career.[11]

Nenagh Hathaway, 2018

[1] The original background color could not be determined. See Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 113.

[2] Variants on the

Virgin and Child theme are discussed in relation to their Byzantine predecessors by Maryan Ainsworth in Helen C. Evans, Ed.,

Byzantium: faith and power. Exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2004, pp. 576-588.

[3] This positive attitude towards copies is discussed at greater length in Refs., Ainsworth, 1998, p. 265.

[4] These images may be related to the appearance of Byzantine paintings of the Virgin and Child in the Low Countries during the fifteenth century. Veneration of the famous Cambrai Madonna, which was brought to Bruges and placed on display at the cathedral in 1440 is a significant example of the transmission of the Byzantine icon model to the Netherlands. See Ainsworth discussion

Purity of Vision in an Age of Transition pp. 257-260. See Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 114. An extended discussion can also be found in Maryan Ainsworth, "’À la façon grèce’: The Encounter of Northern Renaissance Artists with Byzantine Icons",

Byzantium: faith and power. Exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2004, pp. 545-555 and especially 576-581.

[5] Ainsworth also illustrates a similar

Virgin and Child from a Valencian private collection (fig. 258). See Refs., Ainsworth, 1998, pp. 274-275.

[6] Agnew’s gave the picture to David when exhibited there in 1966. Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 114.

[7] For a description of the painting’s condition see Martha Wolff’s description in Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 113.

[8] See Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 114.

[9] For an illustration of the underdrawing see Refs., Ainsworth, 1998, p. 275, fig. 260.

[10] These examples are illustrated in Ainsworth, 1998, p. 274, figs. 256a and 257a; p. 274, fig. 258 and p. 276, fig. 261.

[11] For a discussion on David’s workshop production and relationship with the Bruges and Antwerp open markets see Refs., Ainsworth, 1998, pp. 257-308, especially p. 280.

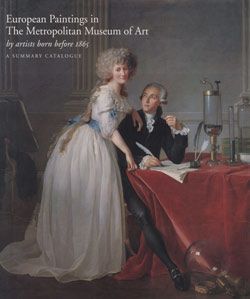

ReferencesKatharine Baetjer.

European Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: by artists born in or before 1865. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980, p. 42, ill. P. 344.

Maryan Ainsworth. ‘Review of ‘Gerard David’ by Hans Van Miegroet, 1989’. Art Bulletin 72 (1990), p. 654.

Katharine Baetjer.

European Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: by artists born in or before 1865. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995, p. 258, ill.

Maryan Ainsworth.

Gerard David: Purity of Vision in an Age of Transition. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, pp. 177, 274 fig. 259.

Maryan Ainsworth in Maryan Ainsworth and Keith Christiansen.

From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Exhibition catalogue (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 291, no. 77, ill.

Martha Wolff in Charles Sterling (et.al).

The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol.2, Fifteenth- to Eighteenth Century European Paintings. New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Princeton: Princeton University Press 1998, pp. 113-114, no. 22, ill.