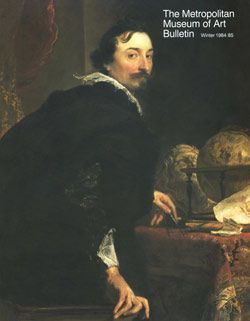

The Artist: For an introduction to Van Dyck, see Walter Liedtke,

“Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641): Paintings” in the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

The Picture: Van Dyck depicts a young redheaded woman with long hair falling loosely about her shoulders. Her face in three-quarter profile, she gazes to one side, eyes lowered and lips slightly parted. Her dark smock or mantle parts at the base of the throat to reveal a loosely painted white undershirt.

Like The Met's

22.221, also by Van Dyck, this painting is what scholars of Flemish Baroque painting call a “head study,” meaning a preparatory work not intended for sale or public display.[1] The practice of painting these studies in Antwerp dates back at least to the work of Frans Floris (1517–70), who, according to his biographer Karel van Mander, “always had a few of those to hand on panels.”[2] Van Dyck learned to paint head studies from Rubens, who produced a large number of them in the decade following his return from Rome in 1609 (see

67.187.99). For both Rubens and Van Dyck, head studies provided a stock of intriguing or affecting faces that could populate large-scale history paintings. It is not clear that head studies were made with a specific final destination in mind—they may simply record chance encounters with appealing sitters.

In the case of The Met’s heady study, Van Dyck used this pensive young woman as the prototype for the Virgin in the

Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria now at Buckingham Palace (RCIN 405332) and dated around 1630 (see fig. 1 above).[3] Here the Virgin turns her head to gaze down at the kneeling saint, in a formula derived from Van Dyck’s study of Titian in Venice. As is usually the case with head studies, Van Dyck has idealized his model in the finished work, straightening the bridge of her nose, rounding her cheeks, and veiling her unruly hair.

The informal nature of head studies is apparent from the facture of this work. Van Dyck painted it on a piece of recycled ledger paper, laid down on panel, and bits of writing can still be glimpsed by the naked eye below the paint layer. Attempts to read the text have yielded a few stray words in Flemish and Italian, apparently recording financial transactions, while scholars have, perhaps optimistically, seen in the penmanship the hands of both Rubens and Van Dyck.[4]

By the middle of the seventeenth century, Flemish head studies inspired the development of so-called

tronies (from a Dutch term roughly equivalent to the English word "mug," in the colloquial sense of “face”).[5] Particularly pioneered by Rembrandt and Jan Lievens,

tronies were finished works, intended for the market, that depicted intriguing but anonymous individuals, often in exotic costume; Vermeer’s

Girl with the Pearl Earring (Mauritshuis, The Hague) is one famous later example, as is The Met’s

1979.396.1. The circulation of these works on the open market caused a retrospective valuation of head studies, particularly following the deaths of Rubens and Van Dyck and the dispersal of the contents of their studios. Intriguingly, the 1691 inventory of Antwerp postmaster Jan-Baptist Anthoine records a “a woman’s head with hanging hair on paper laid down on panel by Van Dyck.”[6] By 1712, The Met’s head study had entered the celebrated collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein.

Early inventory entries occasionally speculated about the identities of models for head studies, identifying them with artists’ servants or family members. There is a suggestive family resemblance between Van Dyck’s pale, russet-haired model and his own self-portraits, for example The Met’s

49.7.25. According to his biographer Bellori, Van Dyck recruited his sister, Susanna, an Antwerp beguine, as the model for Mary Magdalen in an altarpiece he painted around 1628 for her order’s chapel, where he wished to be buried (now Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, inv. no. 403; fig. 2).[7] Viewed in profile as she kisses Christ’s hand, the Mary Magdalen in this painting could be an idealized version of the same woman as appears in The Met’s head study.

Although Bellori’s account and particularly the Royal Collection’s

Mystic Marriage suggest a date for The Met’s head study of about 1628–30, in Van Dyck’s so-called Second Antwerp Period, most scholars have placed it ten years earlier, prior to his departure for Italy.[8] The argument for dating the head study to Van Dyck’s first Antwerp period rests on its resemblance, in terms of both style and sitter, to three other head studies of red-haired female models, now at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum (fig. 3) and in two private collections.[9] On both counts, the similarity among the works has been overstated. The facture of the other sketches has the dry, pastose, at times even gritty quality so typical of Van Dyck’s first breakthrough. The Met’s picture, by contrast, is much more smoothly painted, with the model’s fair skin conveyed through careful blending of pearlescent tones and her loose hair rendered in a calligraphic rather than painterly manner. Likewise, although there is certainly a family resemblance among the sitters, it may be no more than that; individual features such as eyes and nostrils differ noticeably. Van Dyck had six surviving sisters, born between the years 1590 and 1606 (Susanna van Dyck was born in 1600, next after Anthony).[10] It is perfectly conceivable that Van Dyck painted one sister for a group of studies around 1618–20, and then resumed the practice with Susanna a decade later.

Adam Eaker 2020

[1] For Flemish head studies, see Justus Müller Hofstede, “Zur Kopfstudie im Werk von Rubens,”

Wallraf-Richartz Jahrbuch 30 (1968), pp. 223–52; and Julius Held, “Einige Bemerkungen zum Problem der Kopfstudie in der flämischen Malerei,”

Wallraf-Richartz Jahrbuch 32 (1970), pp. 285–90. A catalogue of Rubens’s head studies by Nico van Hout is forthcoming as part of the

Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard.

[2] Hessel Miedema, ed.,

The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the First Edition of the Schilder-Boeck (1603–1604): Preceded by the Lineage, Circumstances and Place of Birth, Life and Works of Karel Van Mander, Painter and Poet and Likewise His Death and Burial, from the Second Edition of the Schilder-Boeck (1616–1618), Doornspijk, 1994, vol. 1, 242v.

[3] Horst Vey has also seen connections between the head study and other works of the Second Antwerp Period; see

Van Dyck: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, New Haven, 2004, nos. III.2, III.10, III.49, III.50.

[4] Liedtke 1984, vol. 1, p.78.

[5] On

tronies, see Dagmar Hirschfelder,

Tronie und Porträt in der niederländischen Malerei des 17. Jahrhunderts, Berlin, 2008; and Franziska Gottwald,

Das Tronie—Muster, Studie und Meisterwerk: Die Genese einer Gattung der Malerei vom 15. Jahrhundert bis zu Rembrandt, Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 164, Munich, 2011.

[6] Erik Duverger, ed.,

Antwerpse kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, Brussels, vol. 12, 2002, p. 91, no. 57; cited by Stijn Alsteens in Alsteens and Eaker 2016, p. 66, no. 5.

[7] Bellori 2005, p. 217; for the altarpiece, see Sarah Joan Moran, “

A cui ne fece dono: Art, Exchange, and Affective Prayer in Anthony van Dyck’s

Lamentation for the Antwerp Beguines,” in

Sensing the Divine: Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe, eds. Christine Göttler and Wietse de Boer. Leiden, 2013, pp. 219–56.

[8] For a summary of the literature, see Stijn Alsteens in Alsteens and Eaker 2016, pp. 64–66, no. 5. Julius Held provided the primary supporting voice for a later date.

[9] One of the private collection studies was sold at Sotheby’s, New York, April 22, 2015, no. 35.

[10] For Van Dyck’s siblings and their birthdates, see Moran 2013, p. 222.