Haverhill Room

Haverhill, Massachusetts, ca. 1805

Matthew Thurlow, Research Associate

The Haverhill Room, installed in Gallery 729 in the American Wing, is the formal parlor (now furnished as a bedroom) from a house that originally belonged to James Duncan Jr. (1756–1822). Duncan was a merchant living in Haverhill, Massachusetts, a town thirty miles north of Boston. He grew wealthy as a partner in the shipping and mercantile business begun by his father, James Duncan Sr. (1726–1818).

Financial success allowed Duncan to build an elegant house in the first decade of the nineteenth century. Its interior represents the Neoclassical style of architecture that prevailed during the early 1800s and provides an appropriate backdrop for the American Wing's strong collection of New England furniture of this era.

Borrowing from antiquity

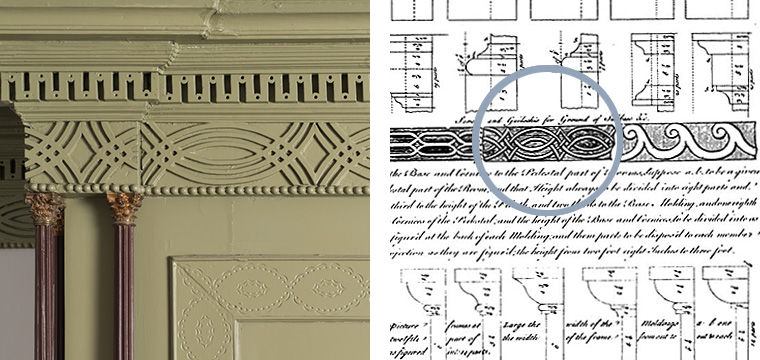

The parlor from the Duncan House is an excellent example of New England's interpretation of the Scottish architect Robert Adam's Neoclassical style. Delicate composition ornament and mahogany pilasters are important signifiers of this architectural mode. There are also echoes of ancient Greece and Rome in such decorative motifs as Etruscan scrolls and urns draped with fabric and festoons of flowers.

Image: Detail of the mantel in the Haverhill Room showing an Etruscan scroll.

Setting

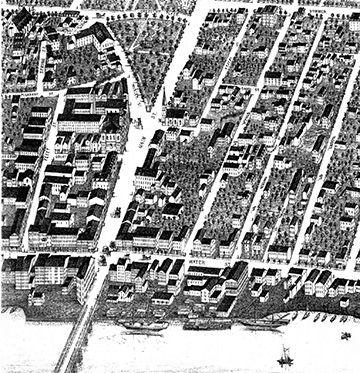

Haverhill, Massachusetts, emerged in the late eighteenth century as an industrial center for the milling of lumber and wheat as well as for distilling, shipbuilding, textile manufacturing, and leather processing. Located on the Merrimack River, with direct access to the Atlantic Ocean, Haverhill also became an important port for foreign and domestic trade.

An 1816 description of Haverhill refers to it as "delightful… with a very pleasant appearance, and an air of importance as a populous and busy town" and mentions the "several handsome dwelling houses" built there.

Image: Detail of a map of Haverhill, ca. 1860. The three-story building attached to the back of the Eagle House hotel is likely the Duncan House. Image courtesy of Haverhill Public Library, Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Exterior

Unfortunately, no photographs exist of the Duncan House prior to its alteration and eventual demolition. However, we can be sure that it consisted of three five-bay, single-pile stories, with two rooms divided by a central hall on each floor. An ell built off the back of the house contained a back parlor, dining room, and kitchen. It most likely resembled the William Haven House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Image: The William Haven House as it appears in John Mead Howells's Architectural Heritage of the Piscataqua (1937).

Interior

Left: Detail of the mantel in the Haverhill Room. Right: Plate 53 in William Pain's Practical Builder (1792) showing the inspiration for the design.

The Duncans' formal parlor had windows on the fireplace wall and on the two adjacent walls. The room opposite the parlor had the same layout and probably served as a less formal sitting room with simpler architectural woodwork. The four upstairs rooms would have been bedrooms for the Duncans, their two sons, and the family's servants.

American builders frequently consulted design books for inspiration in crafting interior woodwork. Neoclassical taste was widely disseminated through publications such as William Pain's Practical Builder, from which the designs for the Duncans' overmantel and the blind-fretwork frieze in the cornice were taken. The fourth edition of Pain's treatise was printed in Boston in 1792 and would have been readily available to the builders of the Duncan House.

The Duncans' furnishings

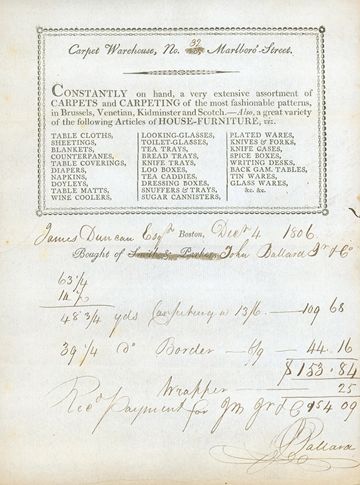

An extensive collection of the Duncans' bills has remained intact, providing us with detailed information about the original furnishings of this room. Because the parlor was where the family entertained guests, the Duncans chose to cover the floor with an expensive Brussels carpet and the walls with a decorative paper and border. Secondary rooms would have featured less costly carpeting or mats and painted or plastered walls.

The family ordered most of the furniture from craftsmen and merchants in Boston, including gilded looking glasses, bedsteads, and painted-and-gilded chairs and settees.

Image:Bill for the original carpeting of the Duncan House. Image courtesy of Historic New England, Phillips House, Salem, Massachusetts.

The Duncans

James Duncan Jr. partnered with his father in the family's shipping and mercantile business. The two men owned numerous vessels that plied trade routes in the eastern United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. They also established a chain of retail stores in Massachusetts and New Hampshire selling the clothing, hardware, pottery, and pewter they imported from Europe.

In 1790, James Duncan Jr. married Rebekah White, a member of another prominent mercantile family. The couple had three children, two of whom—Samuel (1790–1824) and James (1793–1869)—survived infancy. They initially lived in a small house near Duncan's father but soon built a lavish new dwelling to accommodate their growing family. Bills for the furnishings suggest that the house was finished in 1805 or 1806.

Social pursuits

This detail of an 1824 painting by Henry Sargent (1770-1845) entitled The Tea Party depicts an elegant Boston interior informally arranged to facilitate the circulation of guests and spontaneous conversations. Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

The Duncan House was in the bustling heart of downtown Haverhill, Massachusetts, just a short walk from the wharves that provided the family's livelihood. As members of Haverhill's social elite, the Duncans entertained often and elaborately. They used the parlor and dining room to receive their guests. Like other well-to-do families of the early nineteenth century, they restricted their daily meals and activities to less formal areas of the home.

Among the Duncans' friends was John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), who lived in Haverhill as a young boy and later served as senator, secretary of state, and president of the United States.

From house to hotel

According to family history, James Duncan Jr. experienced a reversal of fortune on account of British blockades during the War of 1812. Despite his financial losses, the Duncan family continued to occupy the house for two more decades. When Duncan's widow, Rebekah, moved out of the house in 1832, she leased it to William H. Brown, who converted it into a tavern and inn known as the Eagle House. Brown expanded the building in 1842 and purchased it outright, along with the land on which it stood, from James and Rebekah's son James H. Duncan in 1845. Less than ten years later, he built a seventy-five-room addition directly in front of the earlier structure, completely obscuring the house from view. The two first-floor parlors of the Duncan House served as the hotel's office and reception room.

The inn passed through various hands until it was torn down in 1911 to make room for a movie theater.

Image: Eagle House hotel, ca. 1870

Acquiring the Haverhill Room

After the demolition of the Eagle House inn in 1911, Mrs. F. W. Wallace, an antiquarian from Haverhill, arranged for the architectural elements from the formal parlor and one of the bedrooms to be sold to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both rooms were installed in 1924, although the bedroom was later deaccessioned to make space for new acquisitions.

Image: The Haverhill Bedroom in 1925, as illustrated in R. T. H. Halsey and Elizabeth Towers’s Homes of Our Ancestors (1925). The room was removed in 1947 to accommodate a different period room.

At The Met

The Haverhill Room has belonged to The Met since 1912. It was first installed for the American Wing's 1924 opening along with a bedroom from the house. The exceptional early nineteenth-century interior provided an ideal setting for a portion of the Bolles Collection of New England furniture, acquired by the Museum in 1910.

In the 1940s the Museum undertook a major renovation of the period rooms. The curators decided to refurnish the Haverhill Room as a bedroom, even though the Duncan family had used the space as a parlor. Once again, the decision was driven by the desire to showcase important furniture—in this case, the Boston bedstead (18.110.64). At this time, the Museum's bedroom from the Haverhill House was replaced by the Benkard Room.

Image: The Haverhill Room, transformed from a parlor into a bedroom, ca. 1950.

On exhibit

The surrounds for the windows and doorways of the Duncans' formal parlor are replacements, and their locations were altered to facilitate the circulation of visitors through the American Wing. For example, there were originally six windows, as opposed to the four on view today. But the room does feature its original paneling, cornices, mantel, and overmantel.

When the Haverhill Room was first installed at The Met in 1924, it featured French scenic wallpaper with a hunting theme. This type of wallpaper did not appear in the United States until five to ten years after the Duncan House was built, but the curators retained it when they refurnished the space as a bedroom in the 1940s.

Image: The French scenic wallpaper, which was not appropriate for the room, was removed during renovations in the late 1970s. The current reinstallation of the Haverhill Room was completed in 1979.

Bedstead

This magnificent high-post bedstead represents the collaboration of eastern Massachusetts's most talented craftsmen. Cabinetmaker Thomas Seymour and carver Thomas Wightman probably produced the frame and bedposts, while decorative painter John Ritto Penniman embellished the cornice with flowers. All these craftsmen were based in Boston.

The bedstead originally belonged to Elizabeth Derby West (1762–1814), the daughter of a wealthy Salem merchant. Elizabeth married Captain Nathaniel West and settled in a home called Oak Hill in Danvers, Massachusetts. It is believed that the Salem carver Samuel McIntire later added the gilded basket of flowers with two nesting doves to the bed's cornice and above the doorway of the Wests' bedchamber at Oak Hill. Doves symbolize purity and peace as well as romantic love—all appropriate themes for the setting.

Image: Bedstead on view in the Haverhill Room

Easy chair

Although easy chairs were widely produced in the eighteenth century, few examples from the early nineteenth century survive. The design of this chair is based on one that appeared in George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788). The substitution of turned front legs for the square, tapered legs specified by Hepplewhite implies that the chair was not produced until some time between 1810 and 1815, when rounded legs became more fashionable. Easy chairs, frequently used in bedrooms, were associated with the elderly and the infirm, to whom the cushions and wings provided comfort and warmth. Furthermore, the seat of many easy chairs were fitted with a ceramic or pewter bowl to allow their owners to use them as commodes.

Image: Easy chair, 1810–15. American, made in Massachusetts. Mahogany with reproduction upholstery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, 1931 (31.53.3)

Dressing table and dressing glass

In early nineteenth-century cabinetmaking parlance, this "lady's dressing table" features a "plain arch in sweep front"—a more expensive elaboration on the basic, straight-front model with a single long drawer. According to the English furniture designer George Hepplewhite, the drawers of dressing tables were partitioned to accommodate "combs, powders, essences, pin-cushions, and other necessary equipage."

Dressing tables often featured a built-in mirror, either mounted to the back of the piece or incorporated into a drawer. When no mirror was included, a dressing glass such as this one would be placed on top of the table. The elliptical front and book-matched crotch-veneer panels on this dressing glass suggest the talents of Boston's specialty cabinetmaking trade.

Image: Dressing table and dressing glass on view in the Haverhill Room

Fire screen

This fire screen features a folding shelf for a candle, a refinement found on very few examples. It is a transitional piece that combines the snake feet of the Chippendale period with the oval shape and inlay of the Federal era. Fire screens were used to shield the delicate complexion of a lady's face from the heat of a blazing fire.

Image: Fire screen on view in the Haverhill Room

The Four Seasons

Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall on view in the Haverhill Room

Personifications of the four seasons were common subjects for engravers and printmakers in the eighteenth century, but carved wood statuettes such as these are exceedingly rare. In this set of figurines, the seasons are identified by their attributes: Spring by flowers, Summer by wheat, Autumn by a basket of fruit, and Winter by a muff. The classically influenced dresses, with high Empire waistlines and draped fabric, were the height of fashion during this period. Other than for ships' figureheads, there was little demand in the United States for sculptural carving during this period. The surviving examples of nonmaritime wood sculpture originated almost exclusively in Boston or Salem, Massachusetts.

Keep Learning

Publications

Discover this selection of MetPublications featuring period rooms at The Met.

Federal-Era Period Rooms

Read about American Federal-Era period rooms at the Museum in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.