Shaker Retiring Room

Mount Lebanon, New York, ca. 1835

Alyce Perry Englund, Associate Curator of American Decorative Arts

The Shaker Retiring Room has been installed with architectural elements from a Retiring Room in the North Family Dwelling at Mount Lebanon, New York. Mount Lebanon was a religious community established by the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing of Christ, also known as the "Shakers." Founded on the teachings of a visionary leader, Mother Ann Lee (1736–1784), the Shakers organized a socially progressive Protestant sect that believed in gender and social equality, celibacy, pacifism, and communalism. The Retiring Room, on view in Gallery 734, served as both a bedroom and place to retire to "in silence, for the space of half an hour, and labor for a sense of the gospel, before attending meeting." The Shakers' minimalist lifestyle and spiritual discipline manifested in a stylistic preference for highly streamlined designs seen in the Room's built-in cupboards, pegboards, austere furnishings, and stained woodwork.

View of the Shaker Retiring Room

The Shakers, United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing

The religious sect of United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing began as early as 1747 in England, influenced by the spiritual principles of Quakers and French Camisards. Shakers were distinguished by their excitable worship practice in which they directly communicated with God through prophetic trances, fervent dancing, and singing—behavior that gained them notoriety as "Shaking Quakers" or "Shakers." In the early years of the group, religious followers organized under the direction of Jane and James Wardley, but in 1766 transitioned leadership to Ann Lees Standerin (1736–1784), commonly known as Mother Ann Lee. In England, Ann Lee and the Shakers frequently suffered derision and imprisonment for their religious beliefs, which were seen as blasphemy in an era dominated by the Anglican Church. While jailed, Ann Lee experienced a spiritual vision in which Jesus Christ dwelled within her and spoke through her. These visions compelled her to establish a Shaker Church in the United States.

The Shakers in the United States

In 1774, Ann Lee and eight members of the Shakers traveled from Liverpool, England, to New York on the ship Mariah. The small band of Shakers acquired land in Niskeyuna (later renamed Watervliet), near Albany, New York in 1776, and established their first religious community. Between 1780 and 1783, Ann Lee and her followers engaged in missions across New England in order to recruit new members. Increasingly, people were drawn to Ann Lee's moving oratory and the Shakers' membership grew. In 1784, the Shaker community suffered the loss of Mother Ann Lee. Following her passing, rising leaders like James Whittaker (1751–1787), Joseph Meacham (1742–1796), and Lucy Wright (1760–1821) recognized the importance of maintaining unity among the growing flock of Shaker followers.

During the nineteenth century, the United States' population grew from approximately five million to thirty million as the country's borders expanded from Tennessee to California. The nation witnessed the horrors of several wars and rapid changes in political structures, cultural demographics, and socioeconomics. In the period of 1790 to 1860, spiritual fervor and religious revivals, often called America's Great Awakening, intensified and aiming to counteract a perceived cultural erosion. The Great Awakening spread across the nation leading to a rise in evangelical churches and utopian communities. The Shakers were an appealing religious group during this period because they lived by the doctrines of self-sacrifice, communalism, celibacy, pacifism, and gender and social equity.

Mount Lebanon, central ministry, and organization of the Shaker Communities

Between 1785 and 1787, the Shakers established the Mount Lebanon village along what is now known as Darrow and Shaker Roads in New Lebanon, New York, near Albany. The Mount Lebanon site became the center of spiritual and leadership activities within the Shaker community, even as the group expanded exponentially in the nineteenth century. The early leaders of the Shaker community produced a spiritual manual titled Millennial Laws, published in three editions in 1821, 1845, and 1860. The Millennial Laws, which were created in part to create strict boundaries between the Shakers and the outside world, sharply delineated authority within the Shaker community and set rigid rules governing their behavior, dress, and domestic environment in accordance with their religious beliefs. Within the Shaker villages, members were gathered into collectives typically made up of fifty to one hundred men, women, and children, known as families, which were overseen by deacons and deaconesses. Shaker families sought self-sufficiency in their food production, laundries, building maintenance, and schooling, and distinguished themselves by operating specialized industries or communal duties. While Shakers were not seclusionists, they elevated the importance of autonomous communities and appointed trustees to handle business and interactions with the external world. Under this system, the Shaker communities flourished spiritually and economically. At its height, Mount Lebanon had approximately 600 members and a network of buildings and community operations that sprawled across six thousand acres.

The North family Dwelling at Mount Lebanon

J.E. West, North Family Dwelling House, [late 19th or early 20th c.]. Shaker Museum, Chatham NY (1955.7468.1)

The North Family Dwelling was constructed in 1818 and vastly expanded in 1863 to become a towering five-story, nine-bay wooden frame building designated for one of Mount Lebanon's eight work-and-faith units, or families. The massive dormitory possessed highly sophisticated engineering features for the nineteenth century such as steam heating, a water-cooling system, and a ventilation system. To adhere to the strictures of their Millennial Laws, the Shakers incorporated separate bedrooms and staircases for men and women, as well as a commodious meeting room for the combined flock to join in religious observance. In the two basement levels of the North Family Dwelling, a warren of kitchen workspaces supported cooking, baking, food preservation, dairying, and meat storage. On the main level, Shaker members, venerated Elders, and external visitors dined in rooms designated to their station.

A retiring room

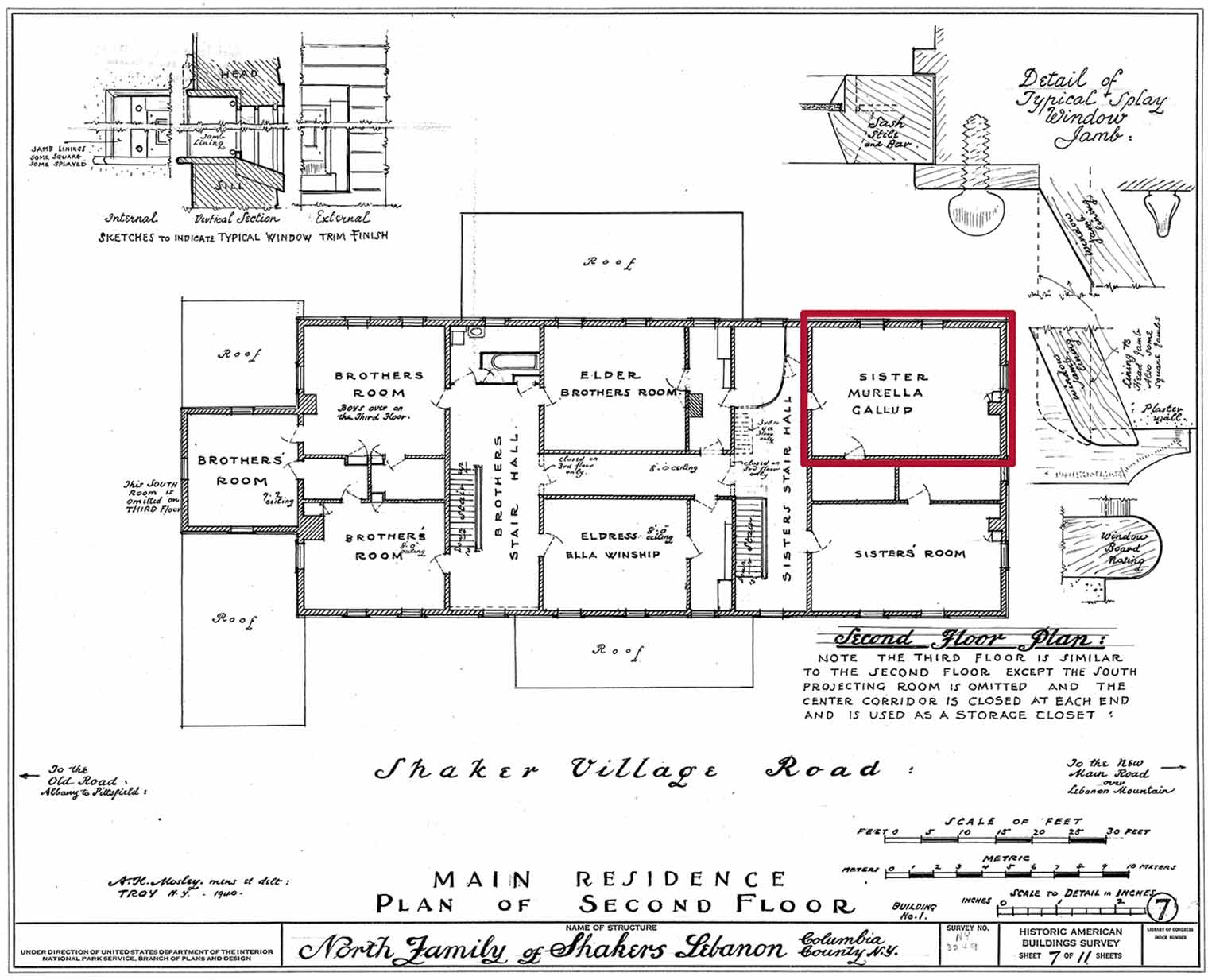

Main Residence, Plan of Second Floor, Shaker North Family, Dwelling House, Shaker Road, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY. Historic American Buildings Surve, compiled after 1933. Library of Congress

Originally, the Retiring Room installed at The Met was one of six bedrooms on the second floor of the North Family Dwelling, and one of three identified for the use of Shaker women. As proscribed by the Shakers' Millennial Laws, their bedroom was a place to retire to, "in silence, for the space of half an hour, and labor for a sense of the gospel, before attending meeting…" in which one was to, "banish from the mind all thoughts of a secular nature, as well as all vain imaginations or worldly temptations." Once the Shaker Sisters had achieved this goal, they descended the adjacent stairwell to the Meeting Room and Chapel one floor below this room.

View of the Shaker Retiring Room

As in many Shaker interiors, a pegboard runs around the room to suspend objects from the floor for more efficient storage and daily cleaning routines. The plentitude of pegboard hooks and ample storage signals the considerable number of women who would have shared a retiring room in a Shaker community. While this room has been installed with only one example of a green-painted bed, it was more typical for several beds to occupy the space. The built-in cupboards, pegboards, austere furnishings, and stained woodwork reveal the meticulous order and discipline within the Shakers community as well as three of the most typical characteristics of Shaker design: utility, simplicity, and beauty.

"Hands to work, hearts to God"

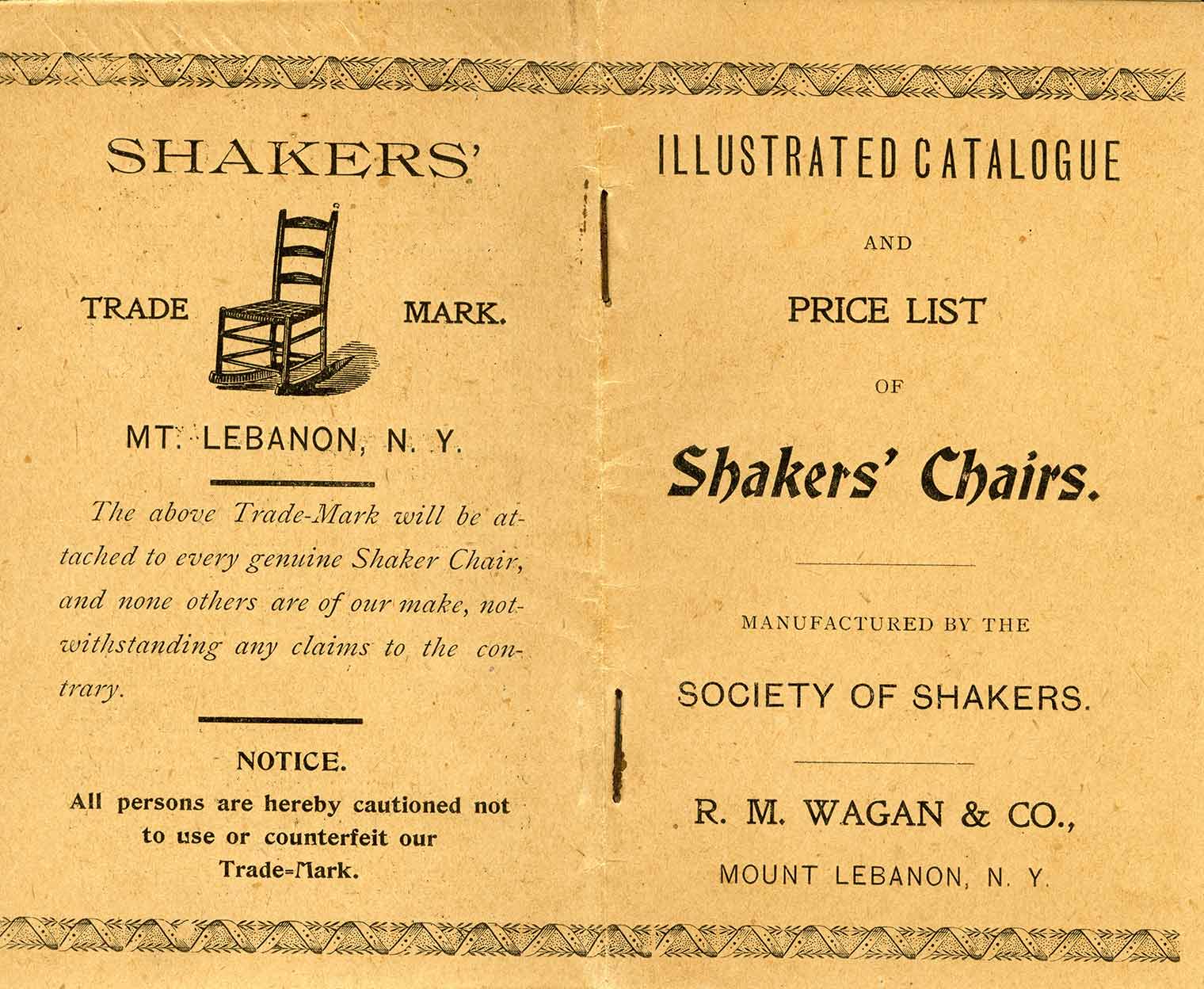

Front and back cover of Illustrated Catalogue and Price List of Shaker Chairs, ca. 1880. Collection of Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, MA (1962.643)

The Shakers are frequently characterized as quaint, simple, or archaic based on presumptions about their rigid and ascetic lifestyle. Yet this characterization undermines the importance of their progressive models of spirituality and communal interests. The Shakers labored for the good of the community as a form of worship. Mother Ann Lee was famously quoted saying "Hands to work, hearts to God." Through their diligence and ingenuity, they raised revenue to support their communities from the sales of Shaker-made products ranging from homeopathic tonics to seeds and agricultural equipment, to clothing and furniture.

In the nineteenth century, the Shakers were highly innovative in their marketing tactics as well as leaders in agricultural engineering and horticulture. During their peak years of 1820 to 1860, the Shaker communities were a social and economic success, as evidenced by their functional and scrupulously clean buildings, practical furniture, labor-saving inventions, and perfectly tended gardens and fields. The Shakers thrived until the last quarter of the nineteenth century when rising industrialization and urbanization in the United States, combined with changing social and religious attitudes, brought about a steep decline in their membership. From the 1910s to the 1940s, many Shaker communities began to close, but the group left a lasting impression on American culture through their idealism, artistic traditions, and scientific innovation.

The North family at Mount Lebanon

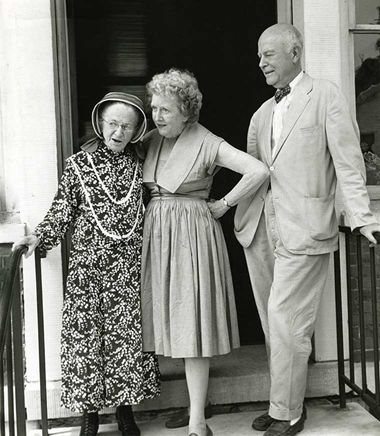

Rosetta Stephens, Leila Taylor, and Mazella Gallup in the Music Room, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY. From James West's Views of the North Family of Shakers. Shaker Museum, Chatham NY (1951.4376.1)

Shaker communities were divided into family units. At Mount Lebanon, the community included the North, Church, Center, Second, and South Families. The Shaker family unit had its own leadership and work delegations in which an equal number of supervising elders of both male and female genders oversaw the maintenance and commercial enterprises of the group. In 1799, the North Family was established for the purpose of recruiting and integrating new community members, while also serving as intermediaries to any visitors from the external world. The Shakers' adherence to celibate lives made recruitment of new members from the external world incredibly important for the survival of their communities. The Elders of the North Family often traveled on religious missions outside of the villages, and functioned in many cases as the ambassadors for the Shaker religion. In the early twentieth century, Shaker membership dropped precipitously causing the closure of many communities. Subsequently, many Shakers were relocated to the North Family Dwelling at Mount Lebanon until the site was closed in 1947.

Sarah Mazella Luke Gallup (1851–1944)

In the Historic American Buildings and Structures (HABS) report for the North Family Dwelling at Mount Lebanon, cataloguers recorded that a "Sister Mazella Gallup" occupied the Retiring Room that is now in the American Wing. While ongoing research into the other occupants continues, Sarah Gallup's story provides an interesting peek into the life of a Shaker Sister. According to Federal Census records, Sarah was born in November 1851 to Margaret and Philip Luke, a farmer, of New Scotland, New York outside of Albany. Between 1870 and 1880, Sarah married Russell Avery Gallup (1850–1884), a farmer from Wright, New York who had worked as a laborer at a neighboring farm. In 1884, Avery died and by 1892 Sarah had moved in with her brother Addison, their mother Margaret, and Addison's three teenage children. By the 1900 Columbia County Census, Sarah Gallup had joined the Mount Lebanon Shaker community at age 50 years and served as a dressmaker and beekeeper in the North Family. Sarah's story is not uncommon. Many widows and orphans found refuge in the support of the Shaker communities. Sarah remained with the Mount Lebanon Shakers until her death in 1944 at age 93. She was buried with her husband at the Gallupville Rural Cemetery in Schoharie, New York.

In the Historic American Buildings and Structures (HABS) report for the North Family Dwelling at Mount Lebanon, cataloguers recorded that a "Sister Mazella Gallup" occupied the Retiring Room that is now in the American Wing. While ongoing research into the other occupants continues, Sarah Gallup's story provides an interesting peek into the life of a Shaker Sister. According to Federal Census records, Sarah was born in November 1851 to Margaret and Philip Luke, a farmer, of New Scotland, New York outside of Albany. Between 1870 and 1880, Sarah married Russell Avery Gallup (1850–1884), a farmer from Wright, New York who had worked as a laborer at a neighboring farm. In 1884, Avery died and by 1892 Sarah had moved in with her brother Addison, their mother Margaret, and Addison's three teenage children. By the 1900 Columbia County Census, Sarah Gallup had joined the Mount Lebanon Shaker community at age 50 years and served as a dressmaker and beekeeper in the North Family. Sarah's story is not uncommon. Many widows and orphans found refuge in the support of the Shaker communities. Sarah remained with the Mount Lebanon Shakers until her death in 1944 at age 93. She was buried with her husband at the Gallupville Rural Cemetery in Schoharie, New York.

Image: Sister Sarah Mazella Luke Gallup. Shaker Museum, Chatham NY (1960.12693.1)

Faith Young Andrews (1896–1990) and Edward Deming Andrews (1894–1964)

In the mid-1960s, curator Berry B. Tracy initiated a program to expand the American Wing's nineteenth-century collections. In the course of this mission, he reached out to Faith Young Andrews with the intent of acquiring Shaker art from the renowned collection she and her late husband, Edward "Ted" Deming Andrews, amassed. From the 1920s to 1960s, the couple worked carefully to earn the trust of surviving Shaker members in order to gain access to their sites and study the intricacies of their beliefs, lifestyle, and industries. As early experts active in the field, Ted and Faith Andrews extended their career from scholarship and collecting into activism and preservation of many sites belonging to the Shakers, from New York to Maine. In addition to furniture, textiles, and implements of industry, the couple saved thousands of archival documents, commercial records, publications, and spiritual materials from Shaker communities, particularly from the period between 1820 to 1860 in many Shaker communities. Institutional letters and memos in The Met collection capture animated negotiations between American Wing curators and Faith Andrews that led to the transformative acquisition of more than fifty examples of Shaker furniture, textiles, and works on paper. These acquisitions served as the foundation from which the Museum grew its Shaker art collection.

In the mid-1960s, curator Berry B. Tracy initiated a program to expand the American Wing's nineteenth-century collections. In the course of this mission, he reached out to Faith Young Andrews with the intent of acquiring Shaker art from the renowned collection she and her late husband, Edward "Ted" Deming Andrews, amassed. From the 1920s to 1960s, the couple worked carefully to earn the trust of surviving Shaker members in order to gain access to their sites and study the intricacies of their beliefs, lifestyle, and industries. As early experts active in the field, Ted and Faith Andrews extended their career from scholarship and collecting into activism and preservation of many sites belonging to the Shakers, from New York to Maine. In addition to furniture, textiles, and implements of industry, the couple saved thousands of archival documents, commercial records, publications, and spiritual materials from Shaker communities, particularly from the period between 1820 to 1860 in many Shaker communities. Institutional letters and memos in The Met collection capture animated negotiations between American Wing curators and Faith Andrews that led to the transformative acquisition of more than fifty examples of Shaker furniture, textiles, and works on paper. These acquisitions served as the foundation from which the Museum grew its Shaker art collection.

Decline and closure of Mount Lebanon

In the twentieth century, membership declined rapidly in Shaker communities. Many of their villages were no longer viable, and they were forced to consolidate remaining members into Mount Lebanon's North Family Dwelling. By 1947, only seven Shakers remained at Mount Lebanon, resulting in the site's closure and subsequent sale of property and structures. By 1929 or 1930, the Darrow School, a private preparatory school, had purchased three hundred acres and forty buildings tied to the Church Family at Mount Lebanon. After the closure of Mount Lebanon in 1947, the Darrow School absorbed a majority of the remaining North, Center, and Second Family buildings and surrounding land into their campus. The historic buildings remained in use at Darrow until 1972 when a devastating fire at the North Family great stone barn, together with substantial maintenance costs, raised concerns around the fate of the Shaker structures. As a result, between 1972 and 1973, the Darrow School sold architectural elements from and eventually razed the remaining structure of the North Family Dwelling.

Acquiring the Retiring Room

Installing the Retiring Room

View of the Shaker Retiring Room

View of the Shaker Retiring Room

The American Wing curatorial staff consulted with leading architectural historians and Shaker scholars—including June Sprigg, former curator of Hancock Shaker Village, collector Faith Andrews, and surviving Shaker members of the Sabbathday Lake community, Brothers Theodore Johnson and Arnold Hadd—on the installation of the Shaker Retiring Room. Documentation was also gleaned from instructions written in the Millennial Laws, print sources and photographs, as well as research of Shaker architecture and the furniture itself.

While the room at The Met includes authentic architectural elements from the Retiring Room at Mount Lebanon, elements like the flooring and plaster were to be recreated and furniture from the Museum's collection was selected to complete the space. Scientific analysis revealed that the Retiring Room's woodwork, pegboard, and built-ins had an original coat of light reddish-brown oil stain, which museum staff stabilized before installation. Evidence of white oil paint was found on all of the window sashes including the transom. Plaster recipes and application techniques used in other Shaker structures in communities in Hancock, Massachusetts, and Sabbathday Lake, Maine, were carefully compared and tested. This research into authentic recipes and applications has ensured that the texture and tinting of the walls and ceiling in the Shaker Retiring Room are to the highest historic standard. The American Wing staff selected many artworks purchased previously from the collection of Edward and Faith Andrews including the swivel chair, slat back chairs (66.10.24, 66.10.25), sewing stand, candlestand, boxes (66.10.36, 66.10.39), and blue-painted chest currently on display.

Shaker furniture design

The streamlined forms and limited ornament of Shaker furniture is an important reflection of their design philosophy. The first generations of Shaker furniture makers were converts who applied skills learned in the external world and trained Shaker apprentices in these techniques. In the nineteenth century, the prevailing Neoclassical style and interest in proportion and geometric order influenced Shaker design. However, the Shakers moved beyond the popular inlay and veneering techniques of typical nineteenth-century Neoclassical furniture into a proto-modernist style that embraced a minimalist aesthetic. Shaker chair and cabinetmakers used joinery and fabrication techniques commonly applied in the outside world, as well as labor-saving equipment like circular saws, mortising machines, and steam-powered lathes. Quintessential Shaker characteristics appear in forms such as trestle benches and tables with turned legs and mill-sawn tops. Single-slat ladder back chairs were made to fit under dining tables, and tall ladder-back chairs were equipped with innovative stabilizing tilters. From 1800 to 1840, in the outside world, painting furniture in vibrant hues or wood-grain patterns was a popular alternative to furniture made from stocks of expensive wood and veneers. The Shakers, too, were not meek in their application of boldly colored paint and stain to their furniture and architecture. The spectrum of finishes not only espoused the spiritual and social guidelines of the Millennial Laws but served as a protective coating to the wood as well.

While Shakers required relatively limited quantities of furniture for their personal use, they generated efficient workshop production techniques to manufacture a great number of chairs and boxes for sale outside of their communities. Catalogues of furniture that circulated to external consumers illustrated hundreds of chairs with options for seat cushions, arm rests, and upholstery. The Shakers capitalized on the mechanized production of interchangeable parts to feed this commercial enterprise.

Bedstead

United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Bedstead. Mount Lebanon, New York, 1830–60. Maple, pine, 71 x 30 x 31 in. (180.3 x 76.2 x 78.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 1981 (1981.226)

Often, Shaker retiring rooms had several beds to accommodate the many same-sex members living in each space. According to the Millennial Laws revised in 1845, the guidelines stated a "bedstead should be painted green—comfortables [bed coverings] should be of a modest color, not checked, striped, or flowered." The modesty of Shaker beds was matched by their efficiency. Wooden wheels affixed to each leg allowed them to be rolled away from walls for easier cleaning around the room. Within Shaker interiors, bright blue, yellow, red, and orange finishes of furniture and architectural elements stood out against whitewashed walls and harmonized with multicolored woven tape seats on chairs and woven carpets. Among this spectrum, Shaker furniture and architecture rarely possessed green finishes. Period accounts and religious texts suggests the association with green to thriving vegetation and thus increasing health of a community in its spiritual nourishment and membership. Toward the beginning of the twentieth century, old finishes were frequently stripped and given a new protective layer of varnish, which makes the survival of the early paint on this bed extremely important in documenting Shaker artistic traditions.

Sewing steps

Shaker sisters may have sewn at a worktable or in a rocking chair. The two-step sewing stool provided a natural rest for the feet, one above the other, so that needlework was elevated to a convenient height on a sister's raised knee when sitting in a rocking chair. The Met's sewing stool was made at the North Family shop and bears the initials of several members who likely used the stool. Those initials are: "MJH/1842," "GHB/1868," and "A. Rosetta Stephens/New Lebanon/1902." The identity of the earliest initials, MJH, has not been confirmed. However, Brother Arnold Hadd, a current member of the Sabbathday Lake Shaker community in Maine, identified GBH/1868 as Grace H. Bowers (1863–1905) who joined the Mount Lebanon Shakers as a small child with her older sister, Lucy, and became a member of the North Family. Sister Ann "Annie" Rosetta Stephens (1860–1948), too, came to the Shakers as a child and gained membership to the North Family on September 5, 1871. According to accounts, Annie's father had been inspired by Elder Frederick W. Evans during his ministries to England around this time and committed his daughter to the Shakers. Sister Annie was a tailoress, wrote poetry and essays for the Shaker Manifesto, and ascended to positions of leadership serving as a deaconess in the North Family.

Shaker sisters may have sewn at a worktable or in a rocking chair. The two-step sewing stool provided a natural rest for the feet, one above the other, so that needlework was elevated to a convenient height on a sister's raised knee when sitting in a rocking chair. The Met's sewing stool was made at the North Family shop and bears the initials of several members who likely used the stool. Those initials are: "MJH/1842," "GHB/1868," and "A. Rosetta Stephens/New Lebanon/1902." The identity of the earliest initials, MJH, has not been confirmed. However, Brother Arnold Hadd, a current member of the Sabbathday Lake Shaker community in Maine, identified GBH/1868 as Grace H. Bowers (1863–1905) who joined the Mount Lebanon Shakers as a small child with her older sister, Lucy, and became a member of the North Family. Sister Ann "Annie" Rosetta Stephens (1860–1948), too, came to the Shakers as a child and gained membership to the North Family on September 5, 1871. According to accounts, Annie's father had been inspired by Elder Frederick W. Evans during his ministries to England around this time and committed his daughter to the Shakers. Sister Annie was a tailoress, wrote poetry and essays for the Shaker Manifesto, and ascended to positions of leadership serving as a deaconess in the North Family.

Image: United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Sewing steps. Mount Lebanon, New York, ca. 1842. Pine, 11 x 9 1/4 x 10 3/4 in. (27.9 x 23.5 x 27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 1981 (1981.207)

Revolving chair

This Shaker-made chair pivots in all directions on a large iron screw concealed behind the upright wooden column under the seat. Its design reflects a mainstream interest in furniture that optimized one's work and movement, such as the sensational "centripetal chair" debuted by the American inventor Thomas Warren at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The Shakers' adoption of the revolving chair design aligned with their inclination for ergonomic, utilitarian furniture. It is believed that revolving chairs, such as this example with a Windsor-like comb back, were made by the South Family at Mount Lebanon for use within the Shaker community and were not sold commercially.

This Shaker-made chair pivots in all directions on a large iron screw concealed behind the upright wooden column under the seat. Its design reflects a mainstream interest in furniture that optimized one's work and movement, such as the sensational "centripetal chair" debuted by the American inventor Thomas Warren at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The Shakers' adoption of the revolving chair design aligned with their inclination for ergonomic, utilitarian furniture. It is believed that revolving chairs, such as this example with a Windsor-like comb back, were made by the South Family at Mount Lebanon for use within the Shaker community and were not sold commercially.

Image: United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Revolving chair. Mount Lebanon, New York, 1840–70. Maple, white oak, pine, birch, 28 x 16 3/4 x 15 in. (71.1 x 42.5 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1966 (66.10.26)

Chest

United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Blanket chest. Mount Lebanon, New York, 1835–75. Pine, 29 1/8 x 38 3/4 x 19 in. (74 x 98.4 x 48.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1966 (66.10.15)

From 1800 to 1840, furniture painted in vibrant hues or wood-grain patterns was a popular alternative to furniture made from stocks of expensive woods and veneers, in both Shaker and mainstream culture. In a Shaker dwelling house, boldly colored furniture, with their painted and varnished surfaces that were easier to wipe clean, would have stood out against the traditional whitewashed walls of rooms. Microscopic analysis reveals several layers of paint, varying slightly in tint which provides rare and important evidence of Shaker techniques in producing pigmented finishes. Twentieth-century collectors and artists found the painted finishes highly desirable and hunted for furniture, like this chest, with iconic Shaker colors, such as ocher, blue, and rust red.

Rocking chair

Previously reserved for the elderly and infirm, rocking chairs became ubiquitous after the American Revolution. The Shakers produced slat-back rocking chairs both for their own use and for sale to the outside world. With their turned posts, slat or "ladder" backs, and woven seats, Shaker chairs were simplified versions of a centuries-old design that remained popular in part because the component parts were comparatively quick and easy to produce. When marketing their furniture, Shakers trumpeted their attention to detail and quality in an era when mass-produced furniture was synonymous with shoddy construction. Shaker chairs may be identified as to the community origin and the date of manufacture on the basis of stylistic variations in the shaping of posts, stretchers, slats, and finials as well as woods used. In this example, the oval finials, round hand grips, and shaped blades suggest it was made at the Mount Lebanon community.

Previously reserved for the elderly and infirm, rocking chairs became ubiquitous after the American Revolution. The Shakers produced slat-back rocking chairs both for their own use and for sale to the outside world. With their turned posts, slat or "ladder" backs, and woven seats, Shaker chairs were simplified versions of a centuries-old design that remained popular in part because the component parts were comparatively quick and easy to produce. When marketing their furniture, Shakers trumpeted their attention to detail and quality in an era when mass-produced furniture was synonymous with shoddy construction. Shaker chairs may be identified as to the community origin and the date of manufacture on the basis of stylistic variations in the shaping of posts, stretchers, slats, and finials as well as woods used. In this example, the oval finials, round hand grips, and shaped blades suggest it was made at the Mount Lebanon community.

Image: United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Rocking chair. Mount Lebanon, New York, 1820–50. Maple, birch, 38 1/4 x 22 5/8 x 28 in. (97.2 x 57.5 x 71.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1966 (66.10.23)

Wash stand

The high regard for personal and domestic cleanliness inherent in Shaker customs manifested in a multitude of duties relating to hygiene, sanitation, ventilation and diet. The presence of a wash stand in every retiring room denoted the distinct importance, and possibly the spiritual nature, of hygiene rituals in the daily lives of Shakers. This wash stand from the Church Family at Mount Lebanon is an unusually sophisticated example with a tall backsplash and sloping sides as well as a small shelf to hold a cup and the basin insert on the top.

The high regard for personal and domestic cleanliness inherent in Shaker customs manifested in a multitude of duties relating to hygiene, sanitation, ventilation and diet. The presence of a wash stand in every retiring room denoted the distinct importance, and possibly the spiritual nature, of hygiene rituals in the daily lives of Shakers. This wash stand from the Church Family at Mount Lebanon is an unusually sophisticated example with a tall backsplash and sloping sides as well as a small shelf to hold a cup and the basin insert on the top.

Image: United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Wash stand. Mount Lebanon, New York, 1810–30. Pine, 39 1/4 x 30 1/8 x 16 1/16 in. (99.7 x 76.5 x 40.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from Faith and Edward Deming Andrews Collection, 1981 (1981.441.3)

Towel or drying rack

In Shaker communities, tenoned drying racks were less frequently produced than x-shaped folding racks. Their placement in retiring rooms, kitchens, laundries, and shops showed their essential place in the daily activities of the Shakers. While an object of great utility, the streamlined, geometric shaping on the rack uprights and trestle feet correspond to the Shakers' pioneering design aesthetics and proto-modernism that inspired folk art circles and contemporary abstractionists. As a gift from the heirs of Edward "Ted" (1894-1964) and Faith E. (1887-1990) Andrews, this towel rack joins many Shaker works acquired from their collection by The Met.

In Shaker communities, tenoned drying racks were less frequently produced than x-shaped folding racks. Their placement in retiring rooms, kitchens, laundries, and shops showed their essential place in the daily activities of the Shakers. While an object of great utility, the streamlined, geometric shaping on the rack uprights and trestle feet correspond to the Shakers' pioneering design aesthetics and proto-modernism that inspired folk art circles and contemporary abstractionists. As a gift from the heirs of Edward "Ted" (1894-1964) and Faith E. (1887-1990) Andrews, this towel rack joins many Shaker works acquired from their collection by The Met.

Image: United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing ("Shakers"). Towel or drying rack. Mount Lebanon, New York, ca. 1830. White pine, 37 × 27 × 11 in. (94 × 68.6 × 27.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Peter, Garrett, and Edward Andrews, in the memory of their parents, Phyllis C. and David V. Andrews, 2020 (2020.71)

Timeline of Art History: Shaker Furniture

Keep learning about Shaker furniture styles like those found in the Shaker Retiring Room on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

The Artist Project: Tom Sachs on the Shaker Retiring Room

Sculptor Tom Sachs shares his admiration for the Shaker ideology and how their ideas are perfectly reflected in their living spaces.

Simple Gifts: Shaker at The Met (2016)

Explore the exhibition Simple Gifts: Shaker at The Met from 2016, featuring objects from the Shaker Retiring Room and more.

Shaker Museum at Mount Lebanon

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, more commonly referred to as Shakers, is one of the most intriguing and influential religious and social movements in American history.