Wentworth Room

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1695–1700

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate

The Wentworth Room, installed in Gallery 711, is from the Portsmouth, New Hampshire home of John Wentworth (1671–1730) and his wife, Sarah Hunking Wentworth (ca. 1673–1741). The house was built between 1695 and 1700 following their marriage in 1693. The room is furnished with imported and American-made furniture in the William and Mary style.

Originally a best chamber, or bedroom, on the second floor, the Wentworth Room is one of the largest domestic interiors surviving from the early colonial period. Early eighteenth-century diaries reveal the best chamber was used for dining and entertaining in addition to sleeping. The room probably contained a high bedstead with a handsome set of bed hangings, but this installation has omitted the bed in order to show a variety of new furniture forms and the range of activities that took place in the room.

An alternate view of the Wentworth Room.

A grand-scale New England home

The Wentworth House on its original site on Manning Street as seen in a 1907 postcard.

Grand in scale, the Wentworth House was built between 1695 and 1700 of heavy oak timbers on a stone foundation and included two full stories and a garret. It featured a large central chimney, an asymmetrical four-bay front facade, and an exterior clad in clapboard siding. The roof was covered with hand-split wood shingles. These are all typical architectural elements of New England houses built from the 1690s until well into the 1850s.

Portsmouth and Puddle Dock

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1760. Hand-colored etching. The New York Public Library

The English settlers who arrived at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in the early 1620s made use of the apparently limitless forests of northern New England and the navigable streams that fed the Piscataqua River. By 1700, investors had built more than sixty sawmills in the Portsmouth area. Pine boards and joists from the mills were exported on vessels bound for Southern colonial ports, the West Indies, Europe, and Africa.

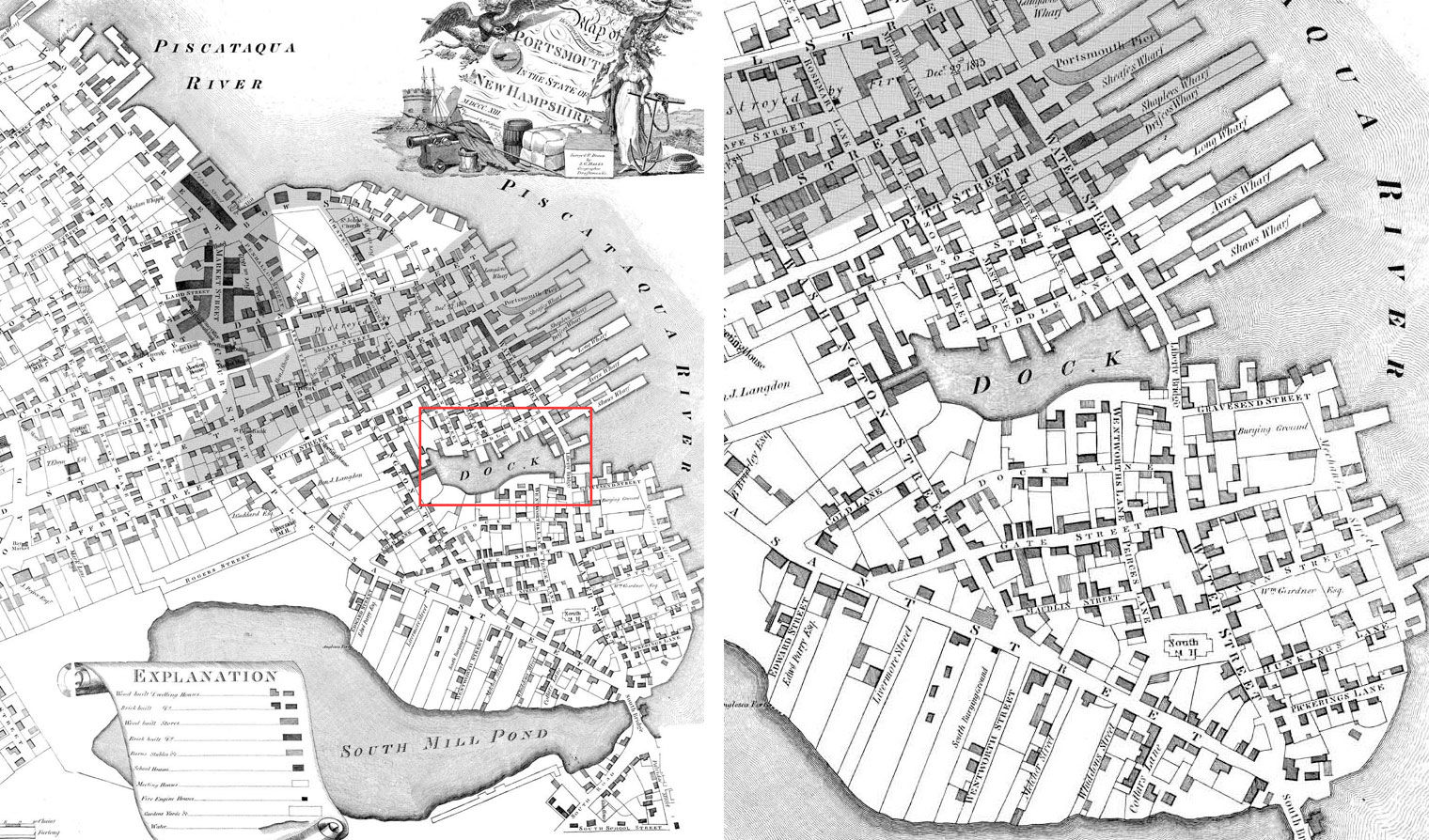

Map of the Compact Part of the Town of Portsmouth in the State of New Hampshire, 1813. Drawn by J.G. Hales and engraved by T. Wightman, Boston, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Library of Congress

With this vast manufacturing base, Portsmouth saw the rise of a merchant class of shipmasters and lumber merchants, who filled their homes with imported furniture and objects. John Wentworth was one of these entrepreneurs, and he chose to build his house by the Piscataqua River on a small inlet known as Puddle Dock.

Raised-panel fireplace wall

The Wentworth Room exhibits architectural features introduced in the late seventeenth century, when vernacular architecture broke away from medieval traditions and began to reflect the Mannerist-inspired characteristics typical of early-eighteenth-century interior decoration.

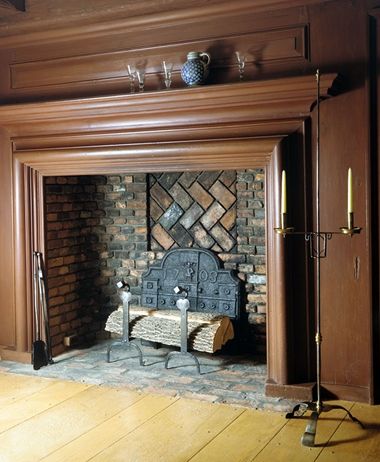

Notice how the woodwork throughout the room is much more elaborate than that in the Hart Room in Gallery 709, which was built in 1680. The fireplace wall is covered with raised, or fielded, paneling framed with bold moldings, while the fireplace opening is surrounded by a beautifully proportioned bolection molding.

Image: Bolection molding around the fireplace in the Wentworth Room.

The staircase

The front door of the Wentworth House opened directly onto this small but beautifully detailed staircase, which rose from the entrance to the attic. At the time the house was built, staircases were gaining new refinements with the addition of newel posts and stair rails supported by balusters. The raised paneling of the stairwell and the spiral-turned balusters in the Wentworth House are rare in the early period of American architecture.

Image: The Wentworth House staircase (Gallery 716) is also in the American Wing, off the Meetinghouse Gallery (Gallery 713).

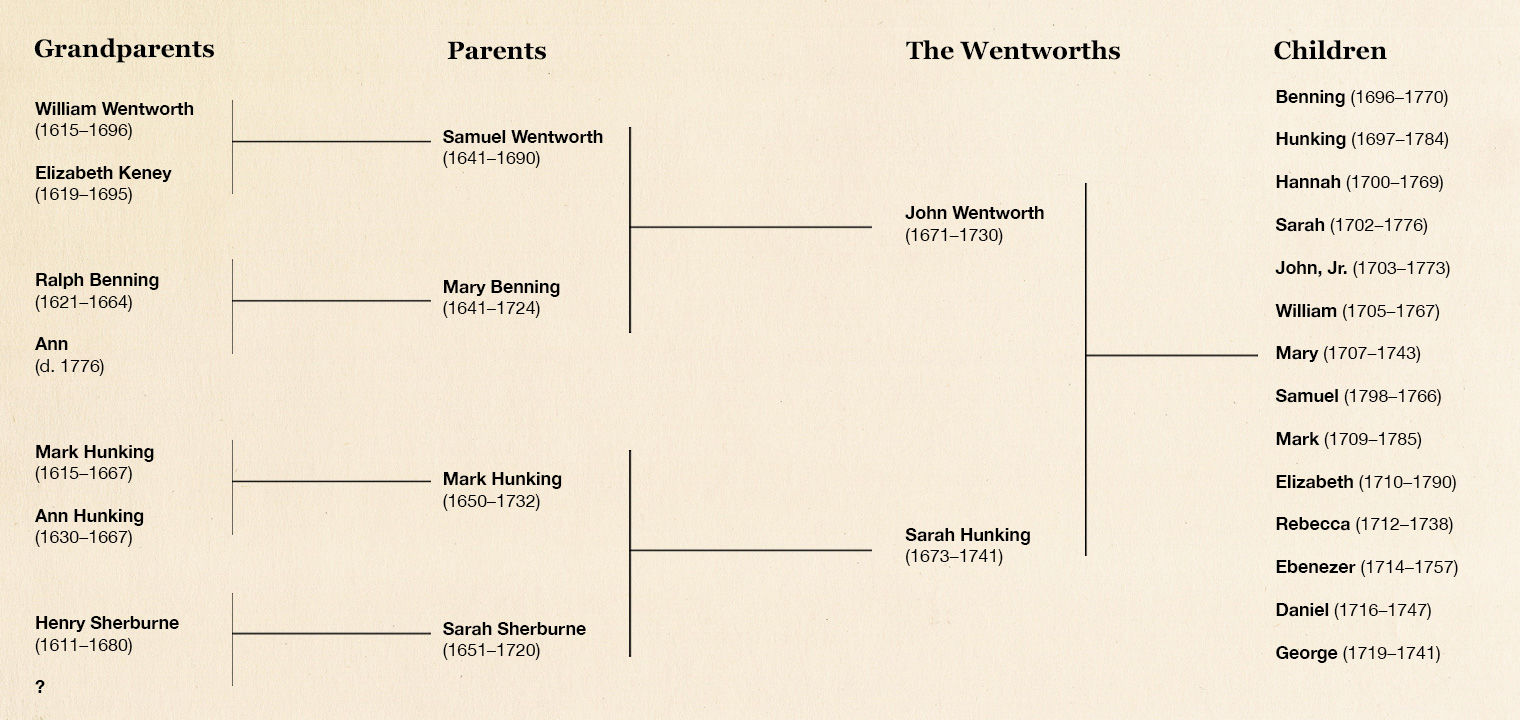

The Wentworths

John Wentworth's family had been in America for two generations and had acquired considerable wealth and standing at the time of his marriage to Sarah Hunking on October 12, 1693. Sarah's father, Mark Hunking, also active in the Portsmouth community and was wealthy enough to give the young couple the land on which to build their new house.

During the early decades of their marriage, John Wentworth served as a sea captain and lumber merchant. On September 12, 1717, King George I appointed Wentworth lieutenant governor of New Hampshire. He held this post until his death in 1730. Sarah and John Wentworth raised fourteen children in their house on Manning Street.

Image: Portrait of John Wentworth, 1671–1730. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

The Wentworth family tree

A Colonial Dynasty

Shrewd business acumen, advantageous alliances with upriver loggers and millmen, and astute marriages allowed the Wentworth family to gain economic and political power, becoming one of leading families of colonial New England. Beginning with the family of patriarch John Wentworth, three generations of Wentworths served in the colonial government of New Hampshire.

Image: Benning Wentworth (1696–1770), the son of John Wentworth, was governor of New Hampshire from 1741 to 1767. New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord

John Wentworth's grandson, also named John Wentworth (1737–1820), served as governor of New Hampshire from 1767 to 1775.

Image: John Singleton Copley, Governor John Wentworth (1737–1820), 1769, pastel on laid paper, mounted on canvas. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: Gift of Mrs. Esther Lowell Abbott in memory of her husband, Gordon Abbott; D.977.175.

Rescuing the Wentworth House

In 1925, a Portsmouth, New Hampshire preservation society contacted The Metropolitan Museum of Art to help preserve the once-grand home of John and Sarah Wentworth. By that date, the house had been removed from its original site and was resting on blocks in a Portsmouth junkyard. It was missing its large chimney, which had been dismantled and thrown into the nearby bay, although some of the bricks were later recovered. To preserve the house, the Museum paid for it to be painstakingly dismantled. The components were stored for more than a decade in a New Hampshire barn before the bed chamber and staircase were moved to New York City and installed in the American Wing in 1937.

Image: The Wentworth house on blocks.

Dismantling the House

Left: December 15, 1926: North elevation with windows removed, and roofing structure exposed. Center: December 19, 1926: South and East elevations of the first and second floor structures. Right: December 23, 1926: South and East elevations showing the supporting beams and the first-floor structure.

In December 1926, a crew working for the Museum dismantled the Wentworth House. Each step of the process was carefully recorded. Measured drawings were made of the interiors, and photographs captured the unveiling of the underlying structure. Peeling away the layers revealed grand, paneled rooms with ceiling heights of eight feet on both floors of the building.

Installation

Left: Eastern half of the fireplace wall. Right: Fireplace wall as installed at The Met before being painted.

At the time of its demolition, the Wentworth House had undergone many changes. It had most recently served as a rooming house. Because of the evolving needs of the house's occupants, many of the rooms had been greatly altered. The first-story rooms had suffered the most, so the Museum's staff selected the main staircase and the best chamber from the second floor for installation.

In 1937 the Museum's staff installed the best-preserved raised paneling, doors, and fireplace molding from the original Wentworth House as fine examples of early colonial interior architecture.

Reproducing elements of the past

When installing a period room, the Museum will often recreate missing details like the twelve-over-eight-pane, double-hung sash windows that were originally in the Wentworth Room. The herringbone brickwork pattern in the back of the fireplace was based on a fireplace found in a Massachusetts house built in 1699. The dark red paint on the paneling and exposed beams matches the room's original color, found beneath multiple layers of later paint.

Image: Wentworth Room fireplace.

Furniture of the William and Mary Style, 1690–1730

At the end of the seventeenth century, domestic interiors began to take on a different appearance based on concepts derived from Baroque design, newly popular on the European continent. These ideas were reinforced in England under the reign of the Protestant rulers who ascended the British throne in 1689, Dutch-born William of Orange and his English wife Mary, daughter of King James II. This Baroque-influenced style was introduced into the American colonies in the 1690s by both immigrant craftsmen and stylish imported furniture.

Furniture in the "William and Mary style," as it commonly became known in the United States, showed a vertical rather than horizontal emphasis, and became lighter in scale. Reflecting the movement and three-dimensional quality of Baroque designs, furniture was no longer confined to strictly rectilinear shapes, like that seen in the Hart Room (Gallery 709). Curves enlivened "Spanish" feet on chairs, scrolling carved chair crests, and the skirts and stretchers of high chests. In case furniture, such as chests and desks, the William and Mary style featured trim lines and large smooth surfaces, which were achieved by abandoning the panel-and-frame tradition and replacing it with finer dovetailed board construction. Walnut and maple became favored over oak, and their natural wood grains (especially burled examples) became valued for their decorative qualities, showcased by the use of veneers.

Image: Dish, ca. 1690. Probably British, Lambeth. King William and Queen Mary depicted on tin-glazed earthenware (delftware). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase of Anita M. Linzee, Bequest, 1937 (37.13.3)

Cane couch

Cane couch, 1690–1710. English. Beech. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1909 (10.125.175)

Although referred to by the English as a "couch," this one-ended caned seat was a form favored in France and sometimes referred to as a lit de repose, or "daybed." It probably served a dual-purpose—as an extra bed at night and extra seating during the day. The seat is softened by a "squab," or generously stuffed mattress. Cane couches were often accompanied by sets of cane chairs, as in the Wentworth Room. In 1717 a New England man named John Welland noted that his principal room held "a Cane Couch[,] Squab & pillow" along with an "Elbow & 6 small cane chairs."

Cane seating furniture made its debut in London during the mid-1660s. Cane, a new and exotic type of upholstery fiber imported from Asia, quickly became popular, and many chairs with cane seats and backs were exported to New England during the last two decades of the seventeenth century.

Oval table with falling leaves

Oval table with falling leaves, 1715–40. American, probably made in Rhode Island. Soft maple, white pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1909 (10.125.133)

This large table has an oversized top and unusually broad proportions and is unique in its grand scale. The table has two gate-legs that support the falling leaves at either end. Its eight turned legs present an imposing array of patterns characteristic of Boston tables. Oval tables with falling leaves could be opened for dining, writing, and other activities. When not in use, the leaves were dropped to form a narrow table that could be placed against a wall. Such versatile tables came in several sizes: in 1690, William Byrd I of Virginia ordered from London "1 Small, 1 Middling & 1 large Oval Table." These easily moved tables were ideally suited to colonial rooms that were often cramped and served many purposes.

High chest of drawers

The striking pattern of arches across the front of this high chest is formed by a series of burl veneers applied in sections. This treatment, beautiful for its asymmetry and irregular wood grain, departs from the proportioned, regular veneers found on other Boston high chests of drawers.

Image: High chest of drawers, 1700–1730. American, probably made in Boston, Massachusetts. Maple, black walnut, poplar, eastern white pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1909 (10.125.704)

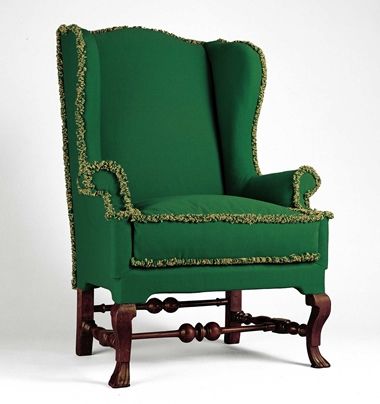

Easy chair

The fully upholstered easy chair was introduced to the colonies in the early eighteenth century, with initial models emerging from Boston. As textiles were costly and upholstering required considerable labor, easy chairs were expensive and accordingly found exclusively in wealthy homes. They were usually placed in the best bed chamber rather than the parlor, with upholstery fabric chosen to match the bed hangings. Easy chairs were often associated with the elderly and the infirm, to whom the cushions and wings provided comfort and warmth. Furthermore, the seat of many easy chairs were fitted with a ceramic or pewter bowl to allow their owners to use them as commodes.

Image: Easy chair, 1730–40. American, made in Boston, Massachusetts. Black walnut, beech, soft maple, maple. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935 (35.117)

Imported ceramics

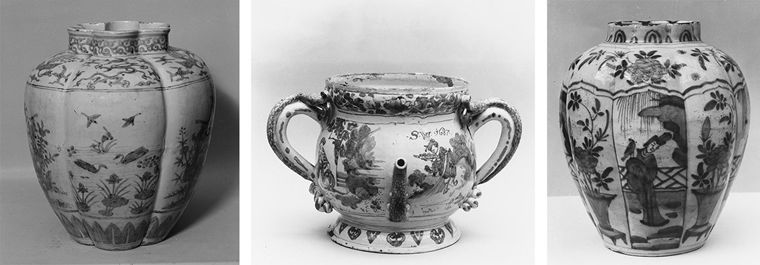

Left: Jar. Chinese. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.12.9); Center: Lambeth Factories [British]. Posset Pot, ca. 1687. Made in London, England. Tin-enameled earthenware. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell S. Carter, 1946 (46.64.15); Right: Jar, 1700–1720, Dutch, Made in Delft, Netherlands. Earthenware. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1926 (26.25.6)

Together, the three ceramics objects placed on top of the chest of drawers (10.125.704) reflect the range of goods and designs brought to colonial America through trade. While the two jars are similar in appearance, with lobed bodies and blue-and-white decorative motifs, they come from two very different locations: the porcelain jar on the left (21.12.9) was made in China, while the earthenware jar on the right (26.25.6) was produced in the Netherlands. Europe's obsession with Chinese porcelain—a difficult material to create—led Dutch potters to imitate its form and decorative schemes in an attempt to satisfy the high demand for expensive and rare porcelain. The object at the center is known as a posset pot (46.64.15). This spouted drinking vessel, made in England, was specifically intended for the consumption of posset, a frothy hot beverage made from eggs, cream, sugar, bread, wine, and ale. The posset pot is also decorated with designs that imitate those found in Chinese porcelain.

Keep Learning

The American Wing

Ever since its establishment in 1870 the Museum has acquired important examples of American Art. A separate "American Wing" building to display the domestic arts of the seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries opened in 1924; paintings galleries and an enclosed sculpture court were added in 1980.

American Furniture, 1620–1730: The Seventeenth-Century and William and Mary Styles

Read about these two stylistic categories of American furniture in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.