Who Did It? Solving the Complex Puzzle of Attribution

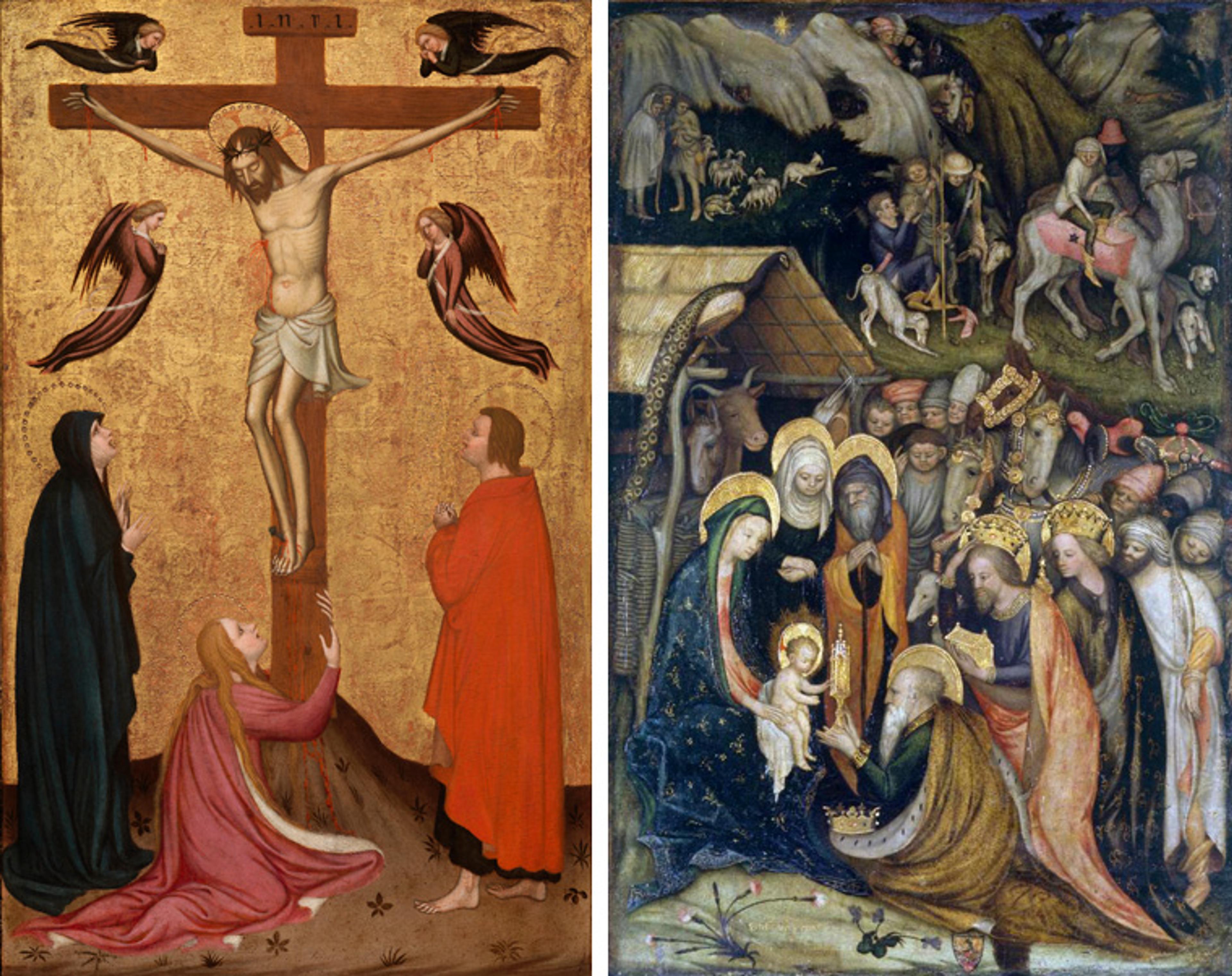

Left: Stefano da Verona (Stefano di Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia) (Italian, ca. 1374/75–after 1438). The Crucifixion, ca. 1400. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 33 7/8 x 20 5/8 in. (86 x 52.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Álvaro Saieh Bendeck Gift; Gwynne Andrews Fund; Charles and Jessie Price Gift; Philippe de Montebello Fund; Gift of Mrs. William M. Haupt, from the collection of Mrs. James B. Haggin, Bequest of Lillian S. Timken, and Gift of Forsyth Wickes, by exchange; Victor Wilbour Memorial Fund; funds from various donors and Gifts of the Marquis de La Bégassière and Cornelius Vanderbilt, by exchange; Marquand Fund; and The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Fund, 2018 (2018.87). Right: Stefano da Verona (Stefano di Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia) (Italian, ca. 1374/75–after 1438). Adoration of the Magi, 1435–36. Tempera on panel, 72 x 47 cm. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan (inv. 349)

«In my last blog post I announced the acquisition of a previously unknown picture by the French-born but Milan-trained fifteenth-century painter Stefano da Verona. As you might guess, we only acquire works when we feel pretty confident we know what the picture is (French? Italian? German? Circa 1420 or 1470?), who painted it, and its importance. That could have been a problem in this case, because although Stefano's work was admired by an artist of the stature of Donatello as well as by the sixteenth-century biographer Giorgio Vasari, he remains a little-known figure for the simple reason that practically nothing by him has survived. The fresco cycles Vasari admired are either destroyed or fragmentary, and his one signed painting, Adoration of the Magi in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan—a staple of art-history manuals—dates from late in his career, in the 1430s. Of course, all of this means that any picture of consequence by him would constitute a major discovery—and if it were an early work, that would be even more fascinating.»

Fortunately Stefano was a brilliant as well as highly distinctive draftsman, and we can glean a fair idea of his stature from his drawings, a stellar example of which The Met was able to purchase in 1996.

Stefano da Verona (Stefano di Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia) (Italian, ca. 1374/75–after 1438). Left: Three Standing Figures (recto); right: Seated Woman and a Male Hermit in Half-Length (verso), 1435–38. Pen and brown ink, over traces of charcoal or black chalk (recto); pen and brown ink, brush with touches of brown wash, over traces of charcoal or black chalk (verso), 11 13/16 x 8 13/16 in. (30 x 22.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1996 (1996.364a, b)

Given the problems I have outlined, it is little wonder that Stefano's authorship of The Met's new acquisition was unrecognized when it was put up for sale in London last May. Thankfully, a colleague sent me an image of the picture after the auction, asking if I might know who painted it. As luck would have it, I was familiar with Stefano's work from all those years ago when I wrote my PhD thesis on one of his contemporaries, Gentile da Fabriano. Still, it took some reflection and an examination of images of his work, isolating details in each of them, to reach some sort of conclusion.

Here are the features that ultimately convinced me that this had to be a picture either by Stefano or someone very close to him.

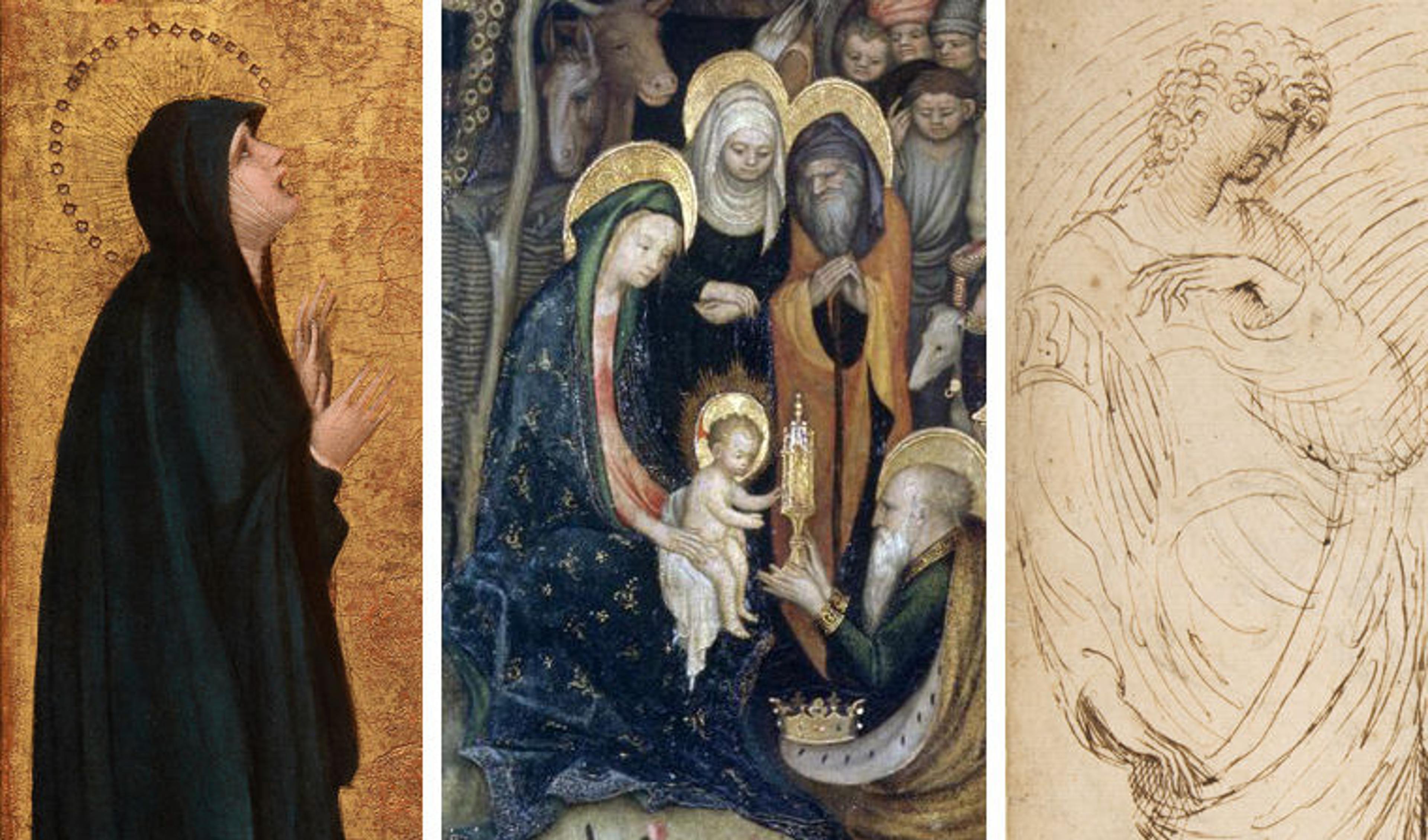

First, a comparison between the mourning figure of Saint John and one of the figures in The Met's drawing. Stefano adopts an graceful, serpentine pose for both the figure at left in the drawing and for the Saint John, a posture that exemplifies the artist's stylistic vocabulary. Apart from the general treatment of the body, with its elongated proportions and elegant tilt of the head, look especially at the malleable treatment of the fingers and that giveaway foot with a high instep. To me, the detail of the small, delicate foot was like a signature for the artist—Cinderella's glass slipper, so to speak.

Left: Three Standing Figures (detail of figure at left). Right: The Crucifixion (detail of Saint John)

Stefano loved elegant gestures and made a point of constantly varying them in his drawings and paintings, so this feature checked out in a remarkable way. So, also, did the shorthand way of creating profile views with a sharply delineated nose. Here, comparisons can be made from The Crucifixion, The Met's drawing, and the painting in the Pinacoteca di Brera.

Left: The Crucifixion (detail of the Virgin Mary). Center: Adoration of the Magi (detail of the Virgin Mary and Jesus). Right: Three Standing Figures (detail of figure at left)

Then there are those angels with their bodies disappearing into trailing drapery—utterly typical of the other painting securely attributed to him in Palazzo Colonna, Rome, Madonna and Child Enthroned.

Left: The Crucifixion (detail of angel at right). Right: Stefano da Verona (Stefano di Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia) (Italian, ca. 1374/75–after 1438). Madonna and Child Enthroned (detail of angels at left). Tempera on panel, 87.8 x 48 cm. Galleria Colonna, Rome (inv. 2041). Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

It all added up to an extremely rare painting by one of the masters of the so-called International Gothic style. At the same time, there is an austerity to the composition that surely indicated a much earlier date than the other surviving pictures. So at this point I contacted a colleague in Italy who knows this area better than anyone else. He had no doubts whatsoever: This was, in his opinion, an important picture by one of the rarest of artists, Stefano da Verona, executed at the outset of his career and reflecting both his French parentage and his training in Milan, when the court of Giangaleazzo Visconti had made it one of the artistic centers of Europe.

A few weeks later I was shown the picture in Florence and was simply entranced by its quality and beauty. I immediately reserved it for The Met. Further research and conversations with colleagues here at the Museum and in Italy pretty much confirmed the matter of its attribution and relative date (acknowledging that our understanding is always a work in progress). Fortunately, two wonderful supporters of the Department of European Paintings stepped forward with generous contributions, and in January the Acquisition Committee approved its purchase.

My esteemed colleague in Italy Andrea De Marchi will write an article about the picture in the near future, but you can already go to our online collection and read a catalogue entry about the artist and the picture. It's a wonderful addition to the collection, but perhaps even more important than that, it's a work that shines a golden light into what had been a dark corner of the history of late Gothic painting and the intersection of French and Burgundian court painting with that of Italy.

Keith Christiansen

Keith Christiansen, John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings, began work at the Met in 1977, and during that time he has organized numerous exhibitions ranging in subject from painting in fifteenth-century Siena, Andrea Mantegna, and the Renaissance portrait, to Giambattista Tiepolo, El Greco, Caravaggio, Ribera, and Nicolas Poussin. He has written widely on Italian painting and is the recipient of several awards. Keith has also taught at Columbia University and New York University's Institute of Fine Art. Raised in Seattle, Washington, and Concord, California, he attended the University of California campuses at Santa Cruz and Los Angeles, and received his PhD from Harvard University.