Technkisi: A Spiritual Connection with Technology

Tecknkisi's logo. Image courtesy of the author

From Don Undeen, Former Senior Manager of MediaLab:

Whenever I showed MediaLab guests around our space, this project was one of my favorites to explain. It exemplifies the spirit of the MediaLab because it takes a deep look at the Met's collection and uniquely uses technology to provoke conversation about what it means to be a museum in the twenty-first century.

In Technkisi, Jaskirat probes the idea of context, a topic that comes up frequently in museums in reference to works that were once used in ritual practices. How do we connect visitors from very different cultures to the original purpose of these objects? Technkisi is one approach to that question that I hope will inspire us to take a closer look at our relationship with ritual objects in museums.

«Technkisi is a kinetic sculpture that "listens," interprets, and responds to the concerns of its user. Inspired by some of the objects in the collection of Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, Technkisi uses technology to recreate the spiritual and sacred experience of partaking in the nineteenth-century rituals Mangaaka power figures and other Nkisi were used in.»

Although the Nkisi in our collection have been tremendously well preserved by the massive efforts of Met conservators, the Museum still struggles to convey the context in which the figures were used. Visitors currently have the ability to learn about the figures during Museum tours, using the Audio Guide, or by researching online, but none of these sources allow the visitor to experience what it was actually like to take part in the rituals. New technologies like Technkisi can help the Met to start looking beyond physical preservation and begin exploring how multisensory experiences can help visitors connect with objects in the collection.

The Inspiration and Idea

According to local dialects of the Kingdom of Kongo, Nkisi means spirit or an object associated with a spirit. Primarily carved out of wood, Nkisi were crafted by specialized sculptors. Every figure is unique in form, but they often strongly resemble humans and are nearly a foot or two tall in height. Nkisi are believed to have held spiritually charged materials during ceremonies led by Banganga, or spiritual healers.

Power Figure: Male (Nkisi Nkondi), 19th–20th century. Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Wood, mirror, cloth, paint, pigment; H. x W. x D.: 24 x 9 5/8 x 7 3/4 in. (61 x 24.5 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.50)

Banganga used Nkisi to communicate with the realm of spirits. People from the local community would go to a Nganga (singular of Banganga) for solutions to a number of issues that were prevalent in that society, and it was the Nganga's duty to resolve these issues with their power to summon spirits. The Nganga would initiate these ceremonies by packing the sculpture's stomach, which was considered its spiritual focal point, with a variety of materials such as bird's beaks, animal blood, stones, soil, and fabric.

The context of those rituals was specific to their society and culture and, more importantly, relevant to the time. Unfortunately, we can't recreate the exact experience of these ceremonies in modern times, so I developed an immersive and interactive experience that simulates the experience of these rituals using something we feel connected to today—digital technology.

I created an interactive replica of one of the Mangaaka power figures that would simulate the original ceremonies using digital technology and trigger emotions in our visitors similar to those that were felt in those rituals. In order to do this in a way that people might understand today, I made the replica a symbolic representation of digital technology and the spiritual connection we feel to it.

Constructing the Replica

Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka), 19th century. Kongo peoples; Yombe group, Republic of the Congo or Cabinda, Angola, Chiloango River region. Wood, paint, metal, resin, ceramic; H. 46 1/2 in. (118 cm), W. 19 1/2 in. (49.5 cm), D. 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Drs. Daniel and Marian Malcolm, Laura G. and James J. Ross, Jeffrey B. Soref, The Robert T. Wall Family, Dr. and Mrs. Sidney G. Clyman, and Steven Kossak Gifts, 2008 (2008.30)

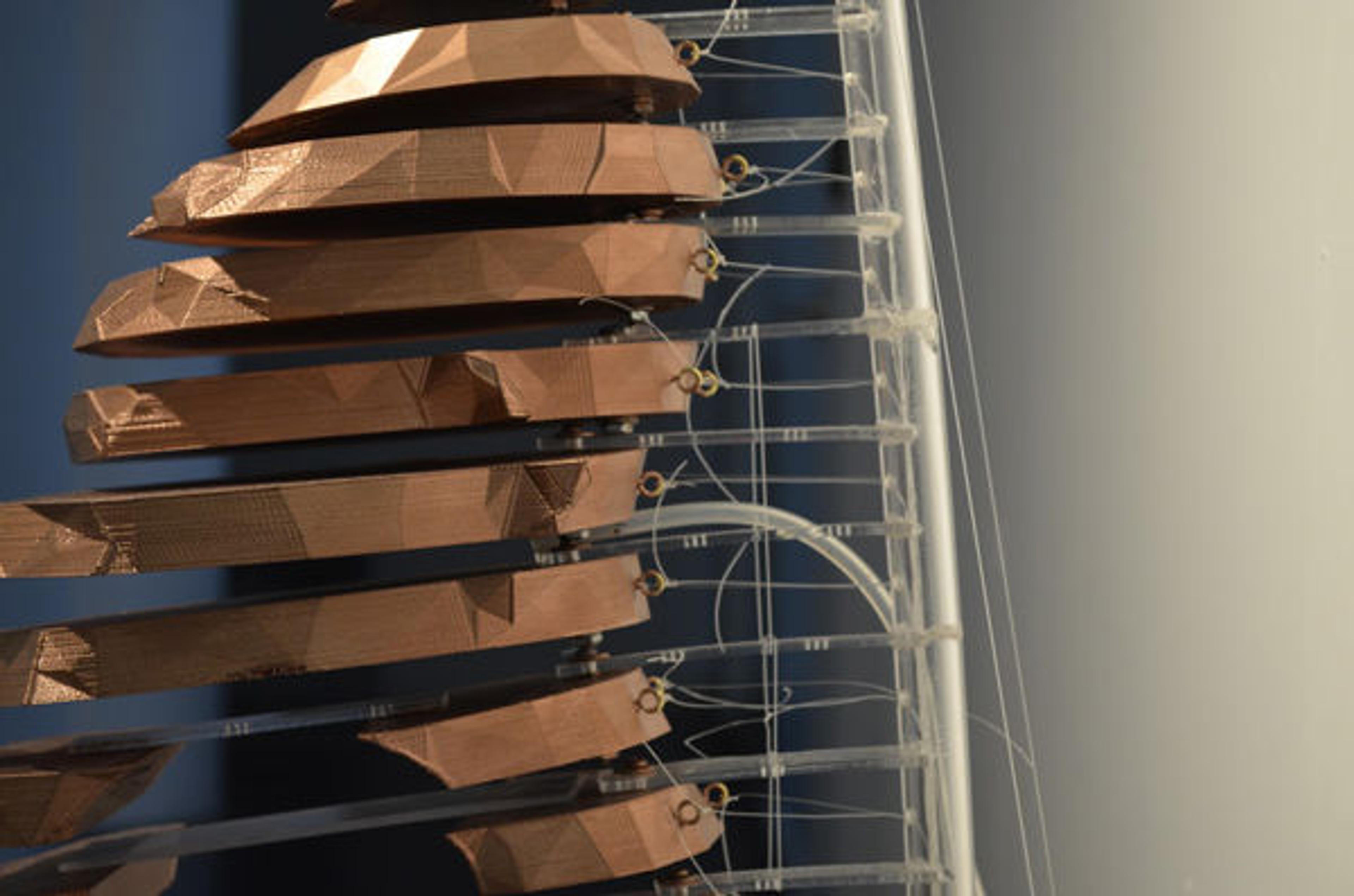

I photographed each side of the power figure, and used Autodesk's 123D Catch to turn those pictures into digital, 3D meshes. I decided to use the power figure's head for the final sculpture because it seemed appropriate to communicate with users through facial features. I then used Cinema 4D, a 3D-graphics software, to digitally manipulate the mesh of the head into a low-poly art image, or a mesh of a low number of polygons that would make up the shape of the replica. I split the mesh of the head horizontally into fourteen layers, each of which was separated by a small amount of even, vertical gaps, and then 3D printed each layer on a 3D Systems CubePro.

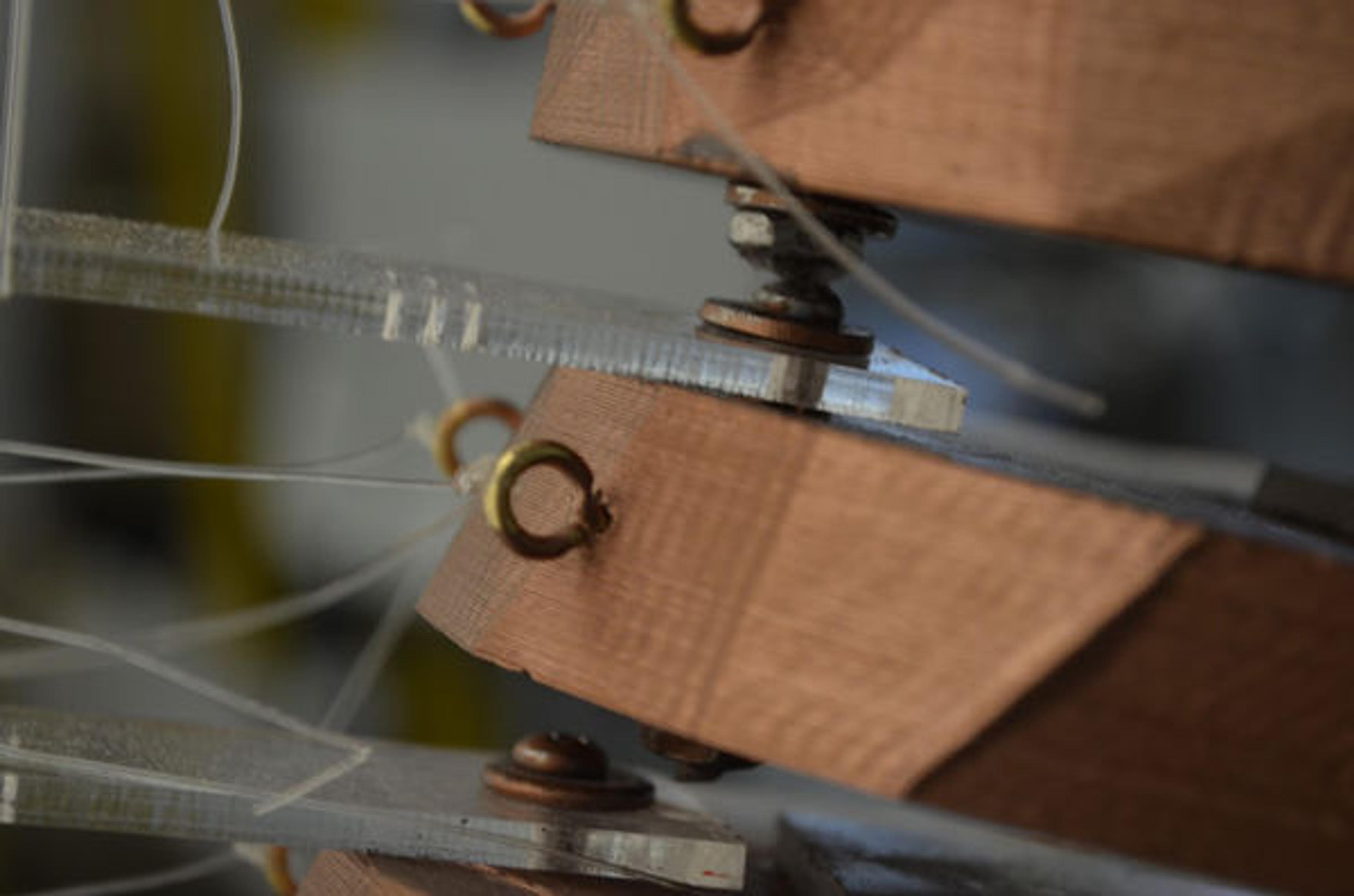

To make the sculpture look more robotic, I spray painted the layers with a metallic copper finish and constructed a plexiglass spine to hold the layers in place. To give the layers the ability to pull away from the spine in different directions, I mounted two hooks on the back of each layer to which I tied a set of transparent fishing wires connected to servo motors.

A closer look at the connection between the hooks and fishing wires. Image courtesy of the author

Given the amount of layers mounted on the plexiglass spine, erecting the sculpture in a vertical, stable position was a daunting task. To stabilize the top, I used three fishing lines connected to the base of the pedestal and positioned the top of the spine. After a few breakages, the sculpture was finally complete.

This side view of the sculpture reveals the complexity of how it was constructed. Image courtesy of the author

One of the fundamental factors in building the sculpture was getting the timing of the ritual's stages right. The sculpture monitors the user's brain activity using a brain-computer interface, and each of the fourteen layers has the ability to rotate forty-five degrees in either direction accordingly. The whole process had to be just long enough for the user to focus on their issue and have the sculpture "absorb" and "release" it.

The final sculpture, Technkisi. Image courtesy of the author

How It Works

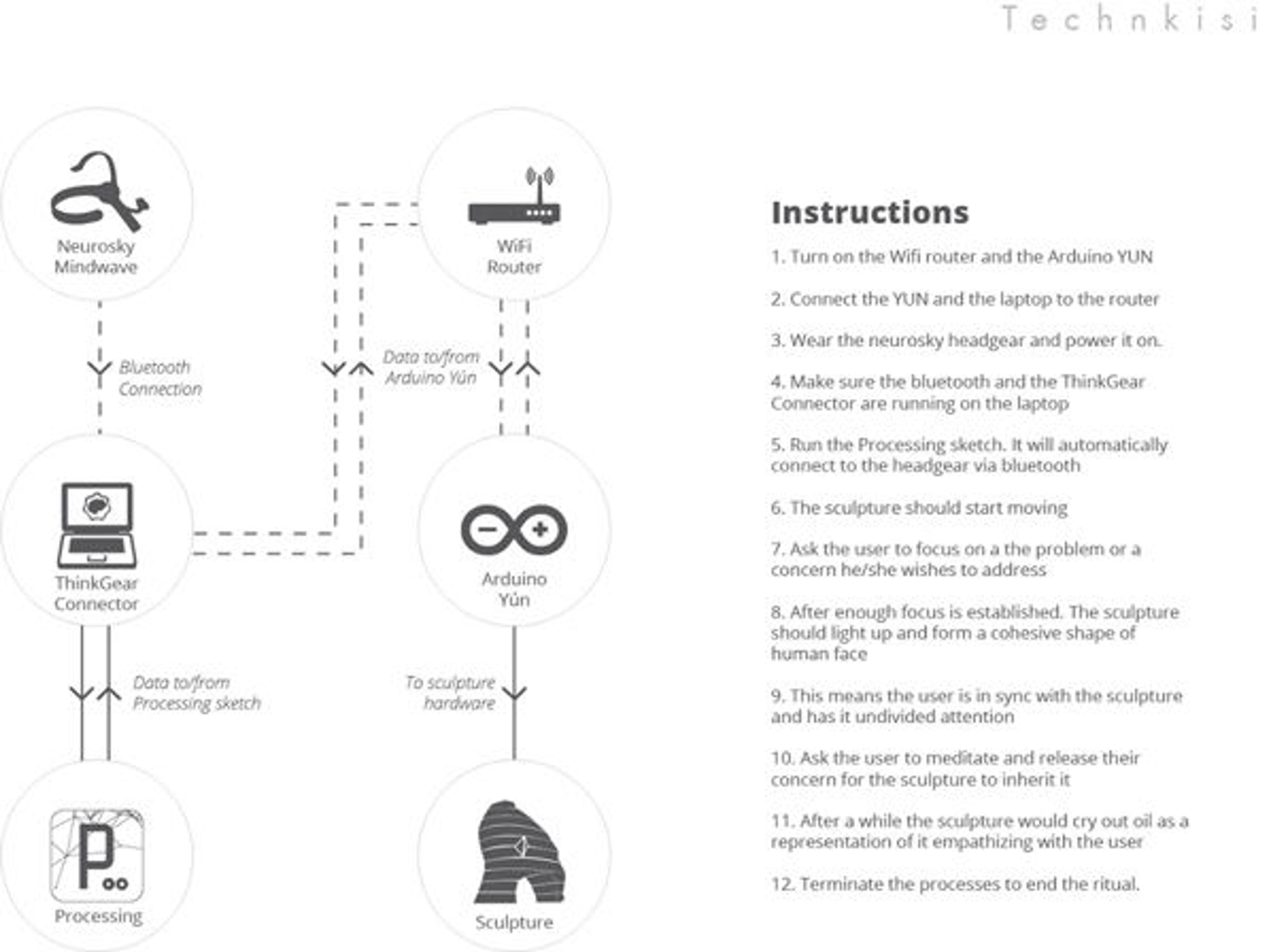

The sculpture is powered by a Neurosky MindWave, a brain-computer interface (BCI), connected to Thinkgear Connector on a laptop. Processing, an open-source programming language, processes the Neurosky MindWave data on the laptop and then translates the phases of the ritual to an Arduino Yun. The Arduino Yun controls the rotation of the four servo motors with the translated phases.

The user starts the ritual by pushing a button on the sculpture and then putting on Neurosky MindWave Mobile headgear. The device then monitors the user's brain waves at full attention and when meditating to establish a baseline. Once the sculpture has established a baseline, it powers up and the layers will automatically begin to rotate according to a preprogrammed algorithm.

The user then focuses on the sculpture while thinking about the issue they want to share with it, like a person would when sharing a worry with a friend. The sculpture will then use the preprogrammed algorithm to quantify the user's brain waves, and once the sculpture detects that the user is giving it their undivided attention, the layers stop moving and orient themselves to depict a face-like shape.

A set of instructions for the person conducting the ritual. Image courtesy of the author

The user will then meditate to let go of their worries, and the sculpture will use the algorithm to process the user's brain waves once again. After a certain period of time, the sculpture will cry out a liquid that looks like oil, which represents that the sculpture has absorbed the user's worries to relieve them of their stress.

A user letting go of her worries with Technkisi. Video courtesy of the author

Next Steps and Final Thoughts

Next steps could include creating a virtual space where users can utilize an Oculus Rift, a popular augmented-reality device, to experience the ritual. Another idea is to use haptic technology, or tactile feedback technology, to give the sculpture the ability to speak to the participant. Lastly, although this is a speculative route to take, another way to enhance the experience would be to construct a layer of distorted reality over a real-time visual data feed. This would allow elements from the physical space to be included in the virtual space, and would make it possible for more than one person to take part in the ritual, irrespective of their location.

This project provided remarkable insights into integrating computational technology in sculpture and allowed me to explore the possibilities of visitors interacting with objects in the Met's collection. I was able to learn about how people feel using shape-shifting robots and devices that respond to a more personal input than touching or tapping. It was fascinating to see how museum technologies are evolving every day and how essential it is for them to explore innovative and creative paths using these technologies.

Special Thanks

Don Undeen, Former Senior Manager of MediaLab, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Yaëlle Biro, Assistant Curator, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dr. Sabine Seymour, Assistant Professor, Parsons The New School for Design

Jaskirat Randhawa

Jaskirat Singh Randhawa was formerly a MediaLab Intern in the Digital Media Department. He is a graduate student in the Parsons The New School for Design's Design and Technology program. Coming from a multidisciplinary background in design and engineering, he loves to create projects driven by creative passion. In the MediaLab, he focused on creating a connection between physical computing, 3D printing, and user experience.