Our Wandering Knight

Art handlers prepare to slide the effigy into its packing crate. Photo by Lucretia Kargère

«Visitors to the Gothic Chapel at The Met Cloisters will notice that one of its residents is missing. The 13th-century tomb effigy of a knight of the d'Aluye family has been exhibited in this gallery since the Museum opened in 1938. However, the sculpture was deinstalled at the end of August to be included in the special exhibition Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven, currently on view at The Met Fifth Avenue until January 8, 2017.»

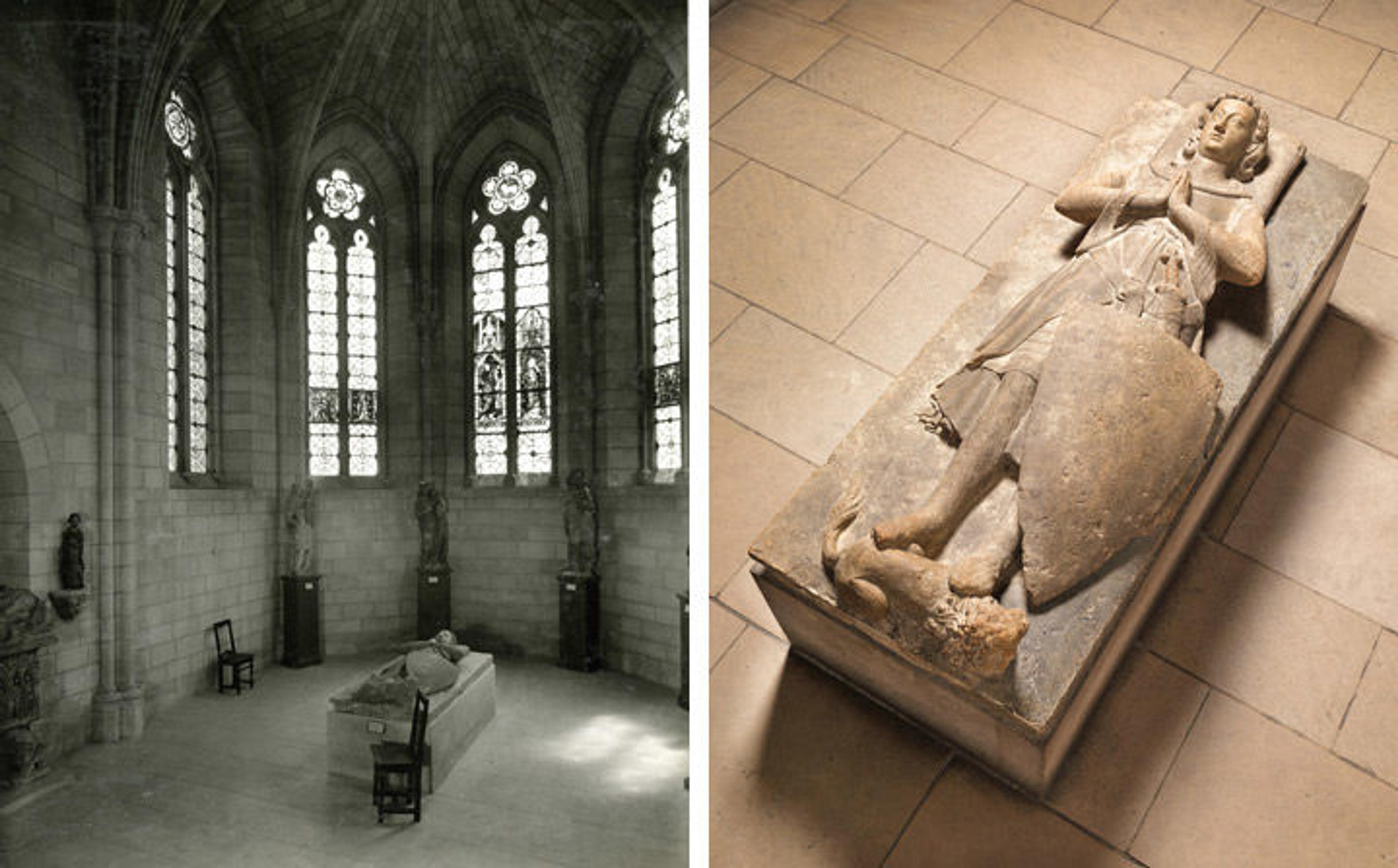

Left: The sculpture as installed in the Gothic Chapel, taken just before the opening of The Met Cloisters in May 1938. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters: Photographs 1938. New York, 1938. Right: Knight of the d'Aluye family, after 1248–by 1267. Limestone, 13 x 33 1/2 x 83 1/2 in. (33 x 85.1 x 212.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.201)

The sculpture was the subject of a yearlong conservation treatment to clean and consolidate the Apremont stone surface in preparation for its inclusion in the exhibition. Originally a tomb at the Cistercian Abbey of La Clarté-Dieu in Touraine, this knight has been identified as either Jean II d'Aluye or his son, Hugues VI, in conflicting sources. Three generations of d'Aluye men are documented as fighting in the Holy Land: Jean's father, Hugues V; Jean himself; and his son, Hugues VI. Depicted in his armor—complete with mail shirt, hood, mittens, chausses on his legs, and surcoat—the knight also has a shield and sword at his side. These items are all expected in an image of a 13th-century knight, but the sword's trilobite pommel is entirely unlike the common cruciform hilts seen in European swords of the period. Helmut Nickel identified the sword as Chinese in origin based on the pommel and the grip wrapping. [1]

A view of the knight's distinctive sword pommel. The sculptor has sensitively rendered various textures, including the draping links of steel mail and the free end of the leather belt.

Perhaps more straightforward than the mystery of where Jean (or Hugues?) acquired his treasured sword is the process of deinstalling the tomb effigy. It took the work of many hands to slide the approximately 1,300-pound sculpture off its base, secure it into a crate for transportation, and remove it from the gallery. Wedges and blocks were placed underneath the stone slab to elevate it above the modern base. Waxed oak rails were then laid underneath the slab and extended into the packing crate, enabling the art handlers to slowly and carefully slide the sculpture into its crate.

Art handlers slide the sculpture along the waxed oak rails and into the packing crate. Video by Christina Alphonso

Once tipped on its side, the crate was lowered down the gallery stairs using a winch. Then the process was basically reversed upon the sculpture's arrival in the special exhibition galleries.

I encourage all interested readers to visit Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven to see the knight amongst other works of medieval art in gallery 899 at The Met Fifth Avenue.

The knight finally at rest in the special exhibition Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven. The sculpture will be reinstalled in the Gothic Chapel at The Met Cloisters later this winter.

Note

[1] Helmut, Nick. "A Crusader's Sword: Concerning the Effigy of Jean d'Alluye." Metropolitan Museum Journal 26 (1991)

Related Exhibition

Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven (September 26, 2016–January 8, 2017)

Christina Alphonso

Christina Alphonso is the administrator at The Met Cloisters.