Eternal Springtime: A Persian Garden Carpet from the Burrell Collection

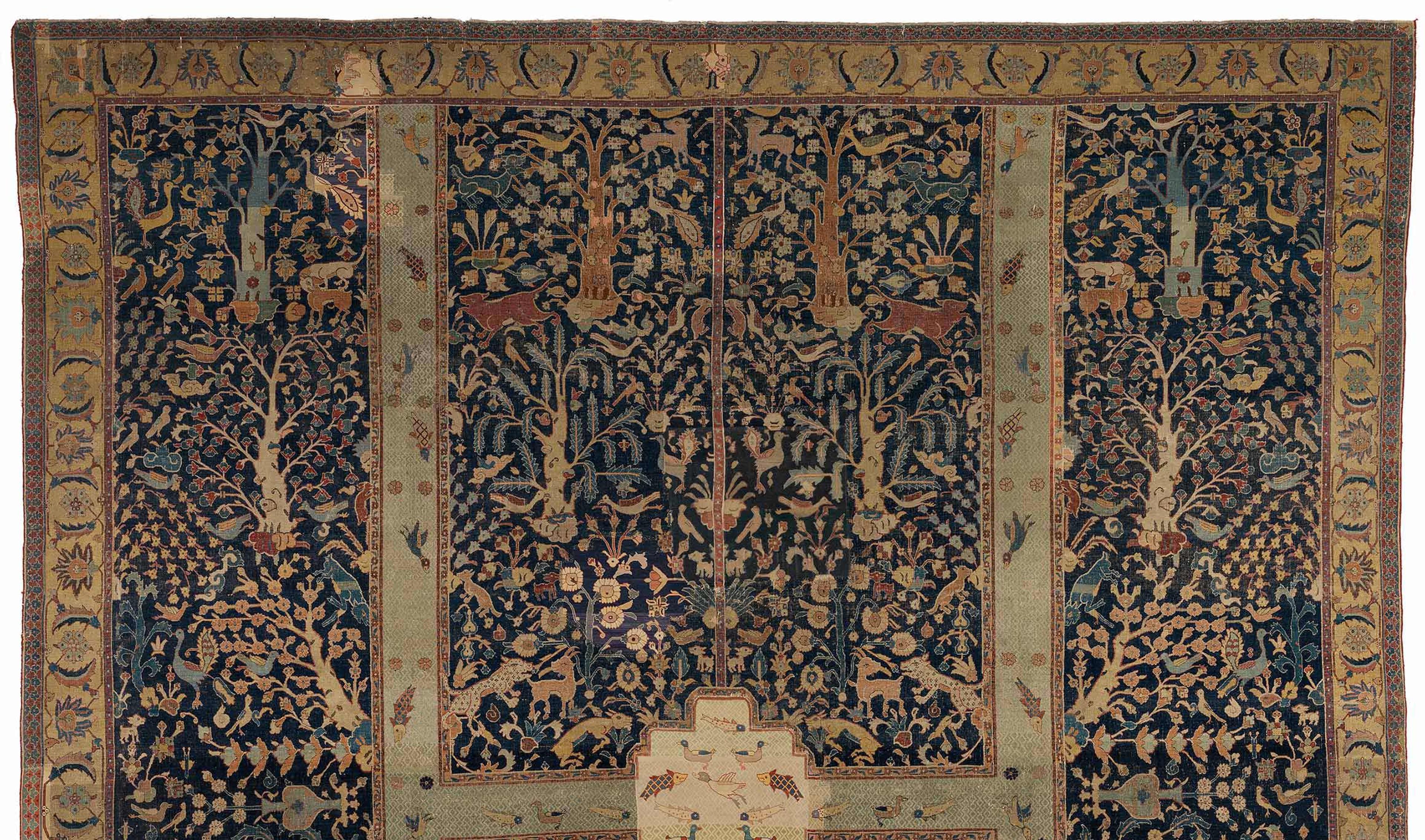

From July to October, regardless of the weather outside, visitors will be able to enjoy springtime, embodied in a grand Persian garden carpet on loan from the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, Scotland. Called the "Wagner Garden Carpet" after a former owner, this carpet will be on view in an American museum for the first time. It is the third-oldest-known Persian garden carpet, dating from the seventeenth century, whereas the three later examples in The Met collection were produced in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The weaving technique of the carpet supports an attribution to Kirman in southeastern Iran, while the later examples are considered products of Kurdistan in western Iran.

The "Wagner" Garden Carpet, 17th century. Iran, Kirman. Cotton warp; wool, cotton, and silk weft; wool pile. Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the approval of the Burrell Trustees. On view in gallery 462

What makes the Wagner Garden Carpet so special? Similar to the other two seventeenth-century garden carpets, this one contains a dizzying array of birds, animals, insects, fish, and even snails amidst flowers and leafy trees. It buzzes with life. Humorous or dangerous encounters between animals take place in a formal setting based on the classic chahar bagh (literally, "four garden") plan of Persian gardens. However, the Wagner carpet does not follow the standard plan with a vertical central water channel intersected by a large horizontal channel to form four rectangles planted with trees and flowers. Instead, two channels run the length of the carpet and are joined by a horizontal channel that does not extend to the lateral edges of the rug. At the point of intersection is a stepped rectangle, which is a repaired area that may have originally contained a pavilion.

Lower half of the "Wagner" Garden Carpet

Although all gardens change over time, the walled garden with water channels maintained its popularity in Iran well into the twentieth century. As in the lower half of the Wagner carpet (above), channels were lined with cypress and chinar, or plane trees, a variety of the sycamore. These trees provided shade and color contrast. In the hot, arid Iranian climate, water is scarce, transported to towns and cities by underground canals that capture snowmelt from the mountains and move it great distances. Landowners would purchase a portion of this water to irrigate crops and their pleasure gardens. While poetry, music, and conversation with friends and family all took place in garden settings, they also provided a protected environment in which to grow fruit and nut trees, vegetables, and flowers such as roses, iris, and lilies. Most of the trees and plants in the Wagner carpet are rendered in a botanically imprecise way, yet the profusion of foliage and blossoms reinforces the impression of a delightful, perfumed bower.

Upper half of the "Wagner" Garden Carpet

For an enclosed space, such as an actual Persian garden would have been, the assortment of fierce and peaceable animals involves very little violence. Only the lions attacking goats (to the right and left in the upper end of the carpet, above) hint that danger could possibly lurk here. Otherwise, even the cheetahs near the horizontal central watercourse appear to want to play with the goats before them. Ducks fly through the trees and swim in the channels, while peacocks stroll beneath the trees. Fish of several types navigate the watercourses, while rabbits, foxes, and wolves gambol through the foliage. Imagine sitting on such a carpet inside a building in winter or in a grand tent in the desert. The delightful, animated scene might just transport one away from either excessive cold or heat. Add to that any one of a myriad of Persian verses that liken a beauty (male or female) to a cypress tree, or a wine cup to a rose, and one can understand how such a carpet conjures up the romantic frame of mind of much of Persian poetry.

Unlike the more stylized garden carpets of the eighteenth century, the specificity of animal species and some trees and plants in this carpet may imply symbolic meanings that are more particular than simply that of paradise. For example, the poet Hafiz (1315–1390) refers to a love object (the cypress) and the tears of the lover (the canal):

The phantom of the stature of his cypress stands constantly in my eye,

Because the place of the cypress is at the bank of the canal.[1]

While such verses refer to a lover and her or his beloved, they also reflect the mystical love of the divine. Likewise, Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207–1273) uses the rose as a metaphor for Divine beauty:

Every rose that spreads fragrance in the outward world—

That rose speaks of the mystery of the Whole.[2]

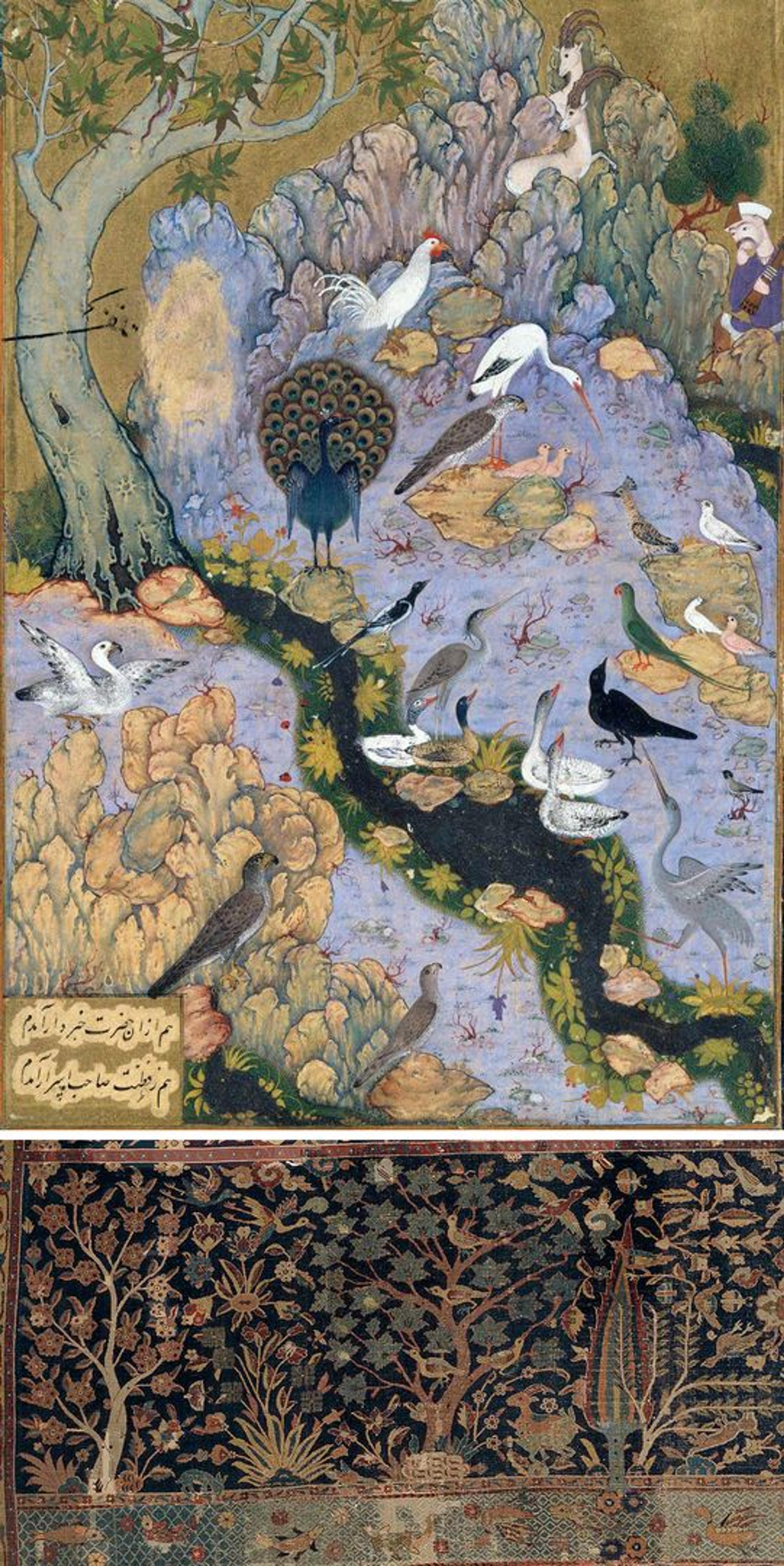

Top: Habiballah of Sava, "The Concourse of the Birds," folio 11r from a Mantiq al-Tair (Language of the Birds) manuscript of Farid al-Din 'Attar, ca. 1600. Iran, Isfahan. Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, painting: 10 x 4 1/2 in. (25.4 x 11.4 cm); page: 13 x 8 1/4 in. (33 x 20.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1963 (63.210.11). Bottom: Detail of the "Wagner" Garden Carpet

Animal symbolism may also have played a role in the Wagner carpet. Birds are often characterized as being able to speak and are celebrated in the poem Mantiq al-Tair (The Language of the Birds) by Farid al-Din 'Attar (1145–1221), in which the hoopoe seeks to rally twenty-nine other birds to set out in search of the mythical Simurgh, a phoenix-like bird who lives at the end of the world. Although the hoopoe is absent from the carpet, the birds depicted may include the nightingale, a perennial favorite in Persian poetry, best known for its attraction to the rose and its call when separated from its beloved flower. Peacocks, which abound in the carpet, represent beauty as an attribute of both the beloved and the springtime garden. Gray doves, on the other hand, are partnered with the cypress, and their cooing, which sounds like the word for "where" in Persian, represents the call for a distant beloved.

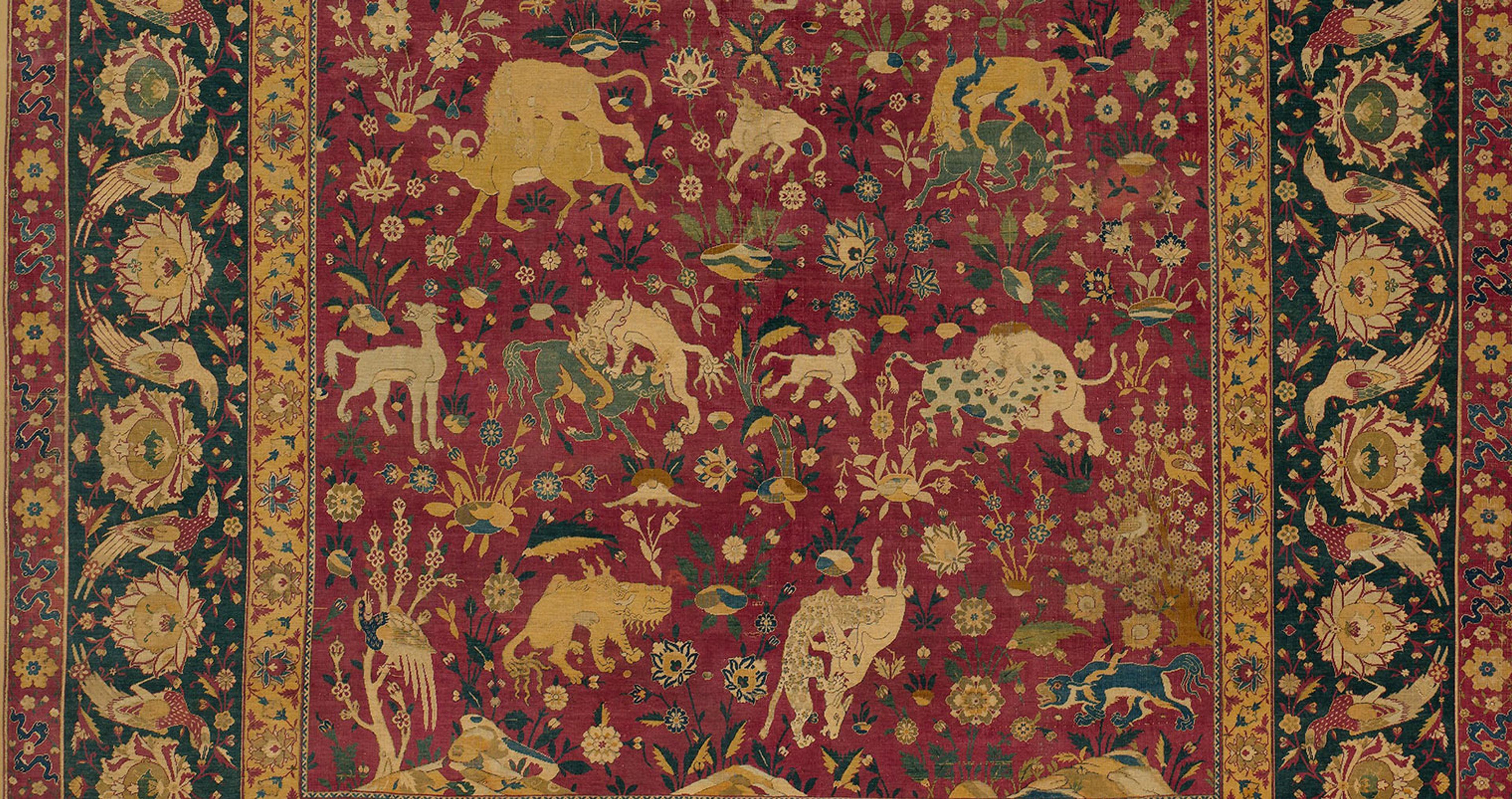

Silk animal carpet (detail), second half of 16th century. Iran, Kashan. Silk (warp, weft, and pile); asymmetrically knotted pile, 94 7/8 x 70 1/8 in. (241 x 178 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913 (14.40.721)

Unlike the birds, the imagery of the four-footed animals in the carpet may have a closer connection to the existing pictorial vocabulary of animal combats in sixteenth-century carpets, and to the motifs of animals in natural settings found in textiles of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, than to poetry. Carpets featuring animal combats were produced in a variety of techniques in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Iran (above), and by the eighteenth century poets were referring to the "lion in the carpet," confirming the perennial place of the king of beasts in some classes of Persian rugs.

Although, when it was first made, the Wagner carpet most likely would have been larger and had different borders than it has now, the impression of glorious nature within a garden is no less powerful in its present dimensions (209 x 170 in.). Its flora and fauna coexist happily, calling to mind the court of the first Iranian king in the national epic, the Shahnama, in which all animals and man lived together in harmony. The abundance of blossoms evokes scented zephyrs and romantic verses, the perfect setting for springtime, captured in a walled garden for eternity.

Notes

[1] Annemarie Schimmel, A Two-Colored Brocade (Chapel Hill, 1992), 164.

[2] Schimmel, Brocade, 175.

Eternal Springtime: A Persian Garden Carpet from the Burrell Collection

On view from July 10 through October 7, 2018, in Gallery 462

Sheila Canby

Sheila Canby is the Patti Cadby Birch Curator in Charge of the Department of Islamic Art.