Traditional Form and a Contemporary Lens: Kara Walker's Resurrection Story with Patrons

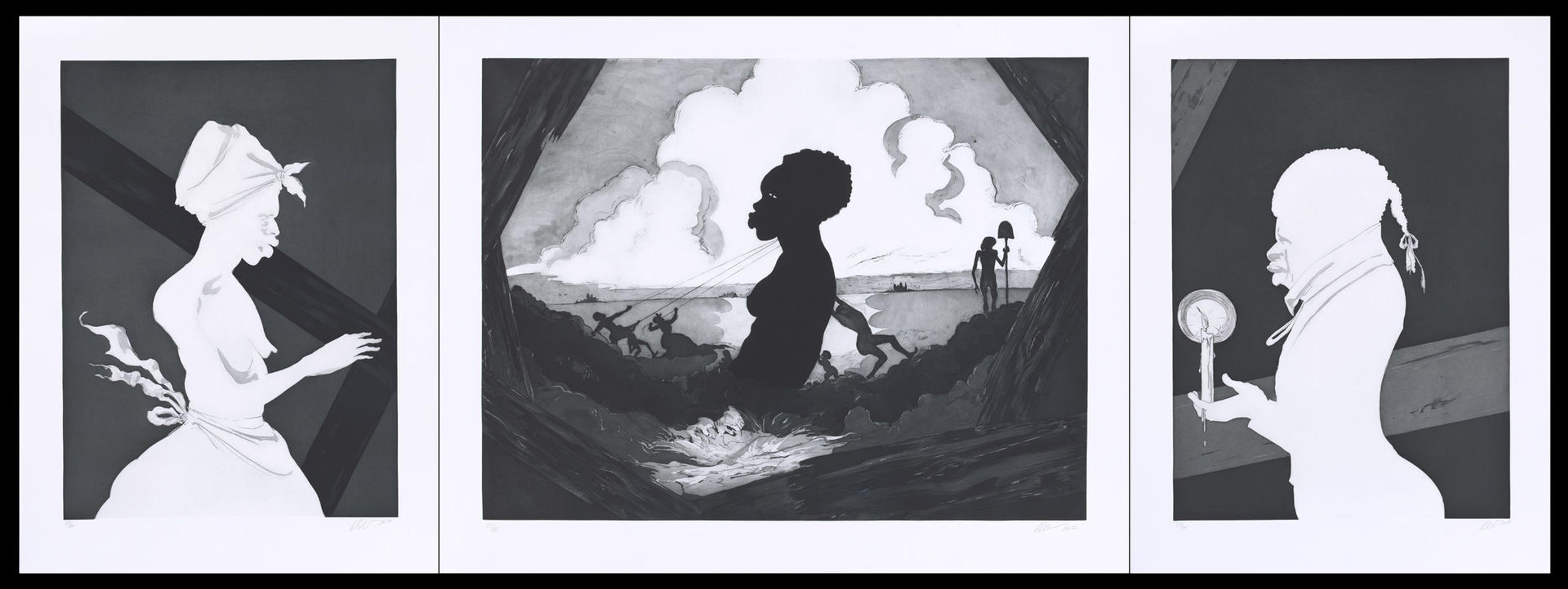

Kara Walker (American, born 1969). Printer: Gregory Burnet. Resurrection Story with Patrons, 2017. Etching with aquatint, sugar-lift, spit-bite and dry-point, Printed on Hahnemuhle Copperplate Bright White 400gsm paper, 39.75 x 30 inches (101 x 76.2 cm); 39.75 x 49 inches (101 x 124.5 cm); 39.75 x 30 inches (101 x 76.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, John B. Turner Fund, 2018 (2018.120a–c). © Kara Walker

On view through January 27, Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints: Hidden and Displayed features seventy works on paper that present their subject matter in a variety of ways—either by purposefully putting things on display, uncovering the unseen, or keeping them hidden altogether. Among the recent acquisitions highlighted in the installation is Kara Walker's Resurrection Story with Patrons (2017), a haunting triptych in which Walker engages contemporary reports of racial violence in the United States and the rise of Black Lives Matter, as well as the imagery, histories, and monuments of Christian martyrdom.

Since 1994, Walker has used the aesthetic of the cut-paper silhouette—an art form used mainly for portraiture that thrived in the eighteenth century—to create powerful works that engage the history and legacy of slavery in America. She has employed the silhouette (and works that mirror the effects of the silhouette) in a variety of media; in addition to large, black-paper cut-outs placed against the stark background of a white wall or sheets of paper (such as Fixin', Pitted, Fished, Pitied, also in The Met collection), Walker has created drawings, prints, pop-up books, films, and sculptures that potently address the trauma of slavery and its legacy.

For Walker, the silhouette is more than a formal choice. Rather, she inherently links the practice and its various associations to representations of a specific historical period, as well as the narratives of race and sex reflective of antebellum stereotypes and prejudices. She has discussed connections between silhouettes and such stereotypes, stating:

The silhouette says a lot with very little information, but that's also what the stereotype does, so I saw the silhouette and stereotype as linked. Of course, while the stereotype, or the emblem, can communicate with a lot of people, and a lot of people can understand it, the other side is that it also reduces differences, reduces diversity to that stereotype.[1]

In Resurrection Story with Patrons, Walker's references to the iconography of Christian martyrdom stem from her 2016 residency at the American Academy in Rome. While in Italy, she encountered numerous examples of these motifs in the Renaissance and Baroque art she saw in churches, museums, and public memorials. Walker not only studied the formal qualities of the country's art and monuments, however; she also used the residency to reflect on the context in which they were created—namely, the role of the state, the church, and other powerful patrons in commissioning such works, as well as their relationship to the artists who produced such memorials.

In 2016, with Barack Obama's two-term presidency in its final months and the Black Lives Matter gaining visibility in reaction to racial violence across the country, Walker considered social and political events in America and the ways they related to the work she encountered in Rome. In response to these influences and events, she created numerous drawings and other works that incorporated concepts of memorial, martyrdom, and the possibility of imagining alternative historical narratives. She continued to explore these themes in works such as Resurrection Story with Patrons after her return to the United States. Made in 2017 with the printmaker Gregory Burnet, the prints contain rich tones and details, and show a wide range of intaglio techniques, including etching, aquatint, sugar-life, spit-bite, and drypoint.

Center panel of Resurrection Story with Patrons

In this triptych, which in form and imagery evokes the altarpiece tradition, Walker imagines a possible memorialization of the African American experience in regards to slavery and the Middle Passage. Dominating the work's central panel is a massive sculpture of the torso of a naked Black woman being raised by several Black men, women, and children of various ages depicted in smaller scale on a rocky shore against the backdrop of a pyramid of white clouds. The ropes the figures pull to elevate the sculpture evoke the violence of slavery and lynching and its commemoration in art, while the shovel held by a male figure on the right resembles a scepter.

Left and right panels of Resurrection Story with Patrons

Bracketing the center image are side panels, which contain depictions of male and female African American figures in antebellum clothing rendered as reverse silhouettes—white against a dark background. Shown in profile, they take the place of the powerful European patrons who would have commissioned such altarpieces. Yet rather than ornate finery to represent wealth and social status, the woman on the left panel is shown half-naked, a modest cloth knotted on her head and a frayed apron functioning as a skirt. On the right panel is a man shown in more formal attire, as revealed by the outline of his jacket and ribbons. Against a dark background, he holds a lit candle that drips wax and (presumably) illuminates the panel as well as the central section. Behind both figures are wooden beams shown in a diagonal that evoke both the cross and scaffolding. In addition to creating the illusion of three-dimensionality, these forms lead our eye to the center scene, where additional bits of wood create a theatrical setting for the elevation of the monumental sculpture.

In this work, like others in her oeuvre, Walker juxtaposes the silhouette's formal beauty with horrific scenes of brutality and oppression, thus connecting the violence of slavery with the artistic and cultural figures that profited from it. As former Met curator Gary Tinterow has noted, "her work forces the viewer to consider the effect of prejudice on both the oppressor and the oppressed and the pernicious, self-perpetuating stain slavery and racism have left on all aspects of American culture."[2] In Resurrection Story with Patrons, Walker engages notions of martyrdom and the function and history of monuments and memorials to imagine how such forms might be applied to both contemporary events and the sins of American history.

Resurrection Story with Patrons on view in gallery 690

Notes

[1] Quoted in Alexander Alberro, "Kara Walker," Index 1, no. 1 (February 1996).

[2] Gary Tinterow, in "Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 2007–2008," Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 66, no. 2 (Fall 2008), 53.

Related Content

Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints: Hidden and Displayed is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 27, 2019.

Explore all of the works on view in the exhibition.

Read more Collection Spotlight articles on The Met's blogs.

Jennifer Farrell

Jennifer Farrell is a curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.