Connecting with Your Met Stories

Today marks The Met's 150th anniversary. We at the Museum have been seeking an appropriate way to celebrate the Museum's endurance as we face so much loss. How can we find togetherness while we necessarily isolate?

On the occasion of the anniversary, we launched Met Stories, a year-long video series and social media initiative that shares unexpected and compelling stories gathered from the many people who visit The Met. This project will now remind us of the period before the terrible one we now endure and the return to togetherness we hope will come soon. On this day, your stories reinforce what connects us.

So far, I've interviewed a veteran who overcame PTSD by visiting the Greek and Roman galleries, a dancer who sees ballet in a brushstroke, a woman who noticed a familiar gleam in her husband's eyes during a drawing class for visitors with dementia, a married couple who first met on The Met's front steps, and a non-verbal autistic man who linked sight and sound in the Asian art galleries. In our most recent episode, a Met staff member stumbles upon a work by Glenn Ligon online and connects its powerful words to her everyday experience as a Black woman, and a visitor unexpectedly discovers her Mongolian heritage and a new place to share it. As we get to know these individuals, the particularities of background and circumstance add up to a powerful collective memory of a Museum bustling with many lives.

Read a selection of the stories we've been gathering below.

Connecting from afar

I work as a medic on an oil rig in West Africa, offshore Gabon. I am the only woman on this rig of 127 people. My clinic is situated in the bowels of this rig, so not many people visit unless they are sick or they need to be medevacked out of here. I long for intelligent conversations, verbal banter about worldly things, or even a challenge to a trivial pursuit game, but alas, no such luck. This is where "My Met" comes in as my savior and [an] anchor to sanity. I eagerly await my newsletter and read it voraciously. And l love being transported into this world of art. I love reading about passionate people who restore great works of art. I am fascinated by stolen works of art. I am in awe of the art historians who teach me about all the different types of art through the ages. And most of all, I love when a piece of art is explained to me [and I learn] what I am supposed to be seeing in the picture! My Met is my anchor to sanity, thank you.

—Bruna D., offshore Gabon on an oil rig.

Connecting with art

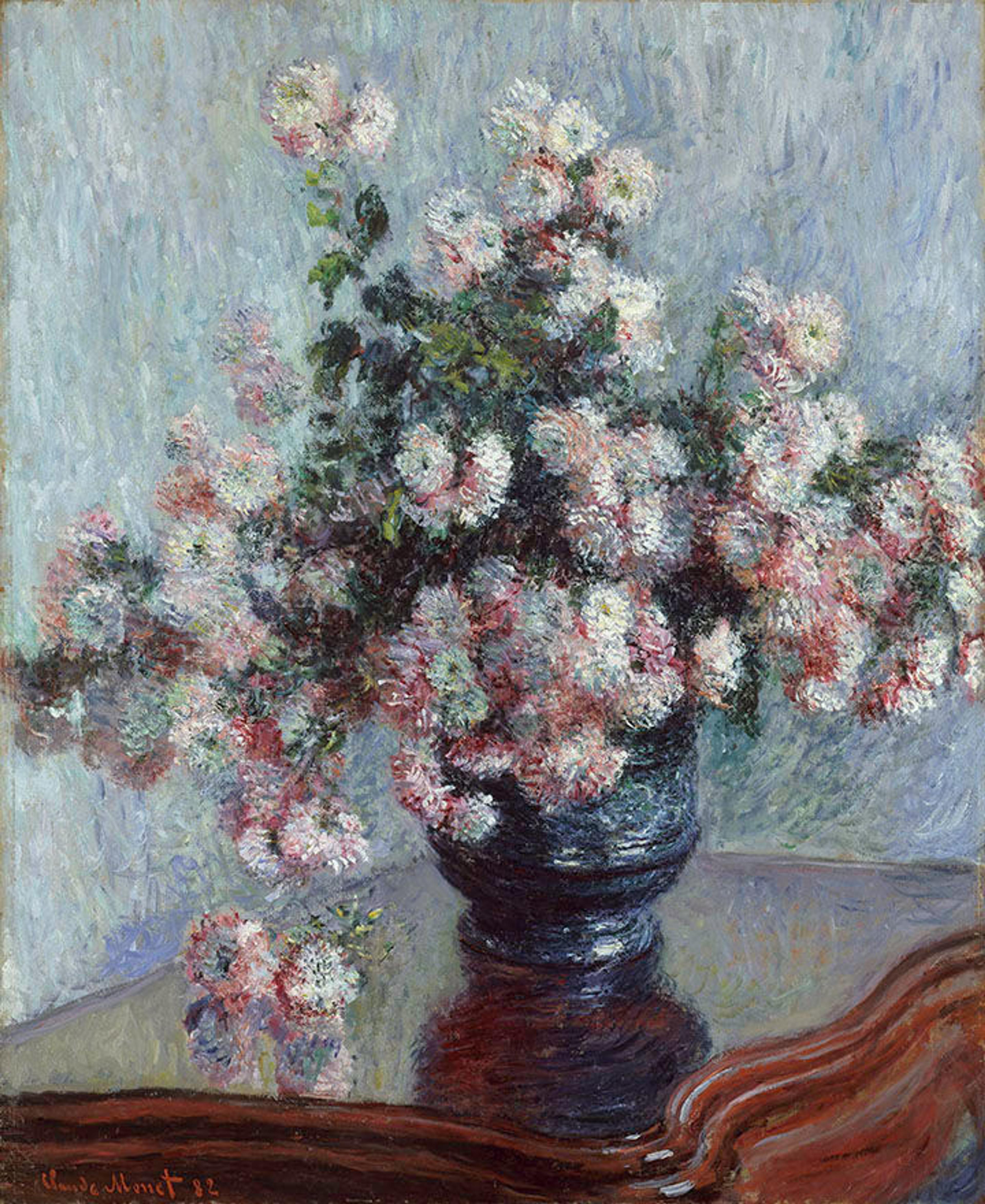

I grew up on West 83rd Street, and the first place I could walk to on my own, after the local library, was The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The building was spacious, free, and one could wander around until something caught your attention. A colorful painting with exuberant brush strokes stopped me in my tracks. Up close, it was about paint and energy, but stepping back, it became a vase of flowers on a shiny mahogany table. Back and forth I went, testing my eyes and their credibility. Monet's Chrysanthemums changed my life. I determined that was what I would do, be a painter. And that is what I became.

—Barbara G., New York

Monet, Claude (French 1840-1926), Chrysanthemums, 1882. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 32 1/4 in. (100.3 x 81.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.106)

I am an artist; a tattooer. I mark people for life, which is my handmade legacy, and I also have been diagnosed with stage four metastatic breast cancer. Since my diagnosis, The Met has become like a church to me.

Death is taboo; you're not supposed to talk about it, but mourning, death, dying, and "the after thing," it's all here at The Met. I'm able to really feel connected by going through and experiencing how each culture deals with all of those things.

[In the galleries, I saw] the lunet, which is a beautiful ["friction drum" from Papua New Guinea]. There are these holes cut out of the side, and when you turn it to the side, it has these eyes carved in, and it looks like birds lined up. You have to stroke it gently, and it makes a wailing sound, an almost human mourning sound. It was used when you wanted the dead spirits to feel like there were a lot of people mourning. So you would stroke these birds, and they make whistling sounds. I stared at it for a very long time. This beautiful item is so well crafted, but there is something [lonely] about the isolation of [playing it]. Someone had to make this instrument because there weren’t enough people to mourn you.

Most people aren't coming into The Met to look at those things, so I feel like I'm really looking at secret things that people walk right by. Everybody has to die. Everyone deals with death, but for me it is right here. I'm comforted by some of the indications of what the living did for the dead. I think about the people that love me and care about me. I want to make sure I don’t become that isolated person. It forces me to connect with people. I don't want to be someone where I need the lunet. I want to be able to have the real thing. I want to really be able to have people remember me for real and the art I have made.

—Sue J., Brooklyn, New York

Friction Drum (Lunet or Livika), Papaun, late 19th–early 20th century. H. 9 1/4 x W. 20 x D. 8 1/4 in. (23.5 x 50.8 x 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1477)

Connecting with each other

In 1965, I was a high school student in suburban New Jersey with a budding fascination for museums and an interest in photography. I would often take the train into Manhattan and wander through the then wonderfully uncrowded galleries of The Met. The old Egyptian galleries were a source of special fascination. Perhaps, I thought, I could bring my camera and tripod to the Museum to capture images of my favorite objects. I duly wrote a letter to the Department of Egyptian Art and asked if this might be possible. "Not usually," I was told, but they would make an exception for me. The next week I showed up at the Museum and was greeted by Nora Scott, the Curator of Egyptian Art, herself. She spent the next two hours with me walking through the galleries, talking about the objects I was trying to photograph, answering questions about Egypt, archaeology, and about what she did when she was not touring teenagers through the galleries. My photographs were terrible, but the day turned out to be an important one for me. I learned that museums are as much about people as they are about things, and I learned that the best curators are never too busy to leave their desks to share their knowledge and passion with those who show an interest. In the years that followed I earned a Ph.D. in art history and went on to spend forty years as a museum curator and director. During those years, I tried never to forget the wonderful lesson I learned that day from Ms. Scott.

—William H., New York, New York

Each week when I ask my twelve-year-old daughter Sabrina what she wants to do on Friday night, her reply is usually, "Let's go to The Met." Ever since I first brought her there when she was an infant in a stroller, she's loved roaming the halls. During her younger years she was mesmerized by mummies; she giggled at the naked Greek statues; she made wishes while tossing pennies into the water surrounding the Temple of Dendur; she looked at koi fish at the Chinese house.

On Mother's Day 2017, when Sabrina was nine [years old], she said she wanted to take me to brunch and to The Met. I decided to create a scavenger hunt for us: We searched for works of art that depict mothers and children. We explored so many corners of the museum.

At 11, Sabrina's tastes started to change. We started strolling through the modern and abstract galleries housed in the back of the Museum. She now likes looking at paintings, she'd analyze them in her eleven-year-old way, which is to say, in a fresh and uninhibited way. There was one painting that she approached and said, "I get this; it reminds me of myself. A bit chaotic in the front, but peaceful in the background."

My daughter has grown up in the halls of The Met. She's learned things, and so have I, about her and about myself. The Museum is where her love of art was forged and mine continues, and it encapsulates our love of New York City.

—Tracey C., Brooklyn, NY

The painting by Henry Raeburn titled The Drummond Children has always been my favorite painting at The Met. I first saw it as a young man and loved it for its simplicity and beauty. Whenever I am in New York and I visit The Met I hope that it is still hanging on the second floor. Many of the people I have taken to see it are now gone, but when I see the painting, they are there with me. I hope that young people who first see it will have the same experience I had.

—Sean C., Las Vegas

Raeburn, Henry (British, 1756–1823). The Drummond Children, ca. 1808–9. Oil on canvas, 94 1/4 x 60 1/4 in. (239.4 x 153 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950 (50.145.31)

What's Your Met Story?

Tell us your Met story using this simple form—you can even upload photos and videos—and you might see your story featured on our social media channels, emails, or website in commemoration of The Met's 150th anniversary in 2020.

Sarah Cowan

Sarah Cowan is an editor and producer in the Digital Department.