530. Introduction: “Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast”

Welcome to the exhibition "Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which examines Western sculpture in relation to the histories of transatlantic slavery, colonialism, and empire.

In this Audio Guide, you will hear the perspectives of contemporary artists on how Carpeaux and other sculptors of his time represented and, in many ways, mischaracterized the idea of freedom in their work. They speak to the many obscured narratives from the 18th and 19th centuries, especially as they relate to the Black experience.

Their discussion begins with one particular artwork: the iconic sculpture called "Why Born Enslaved!" by the French sculptor Jean Baptiste Carpeaux from 1868.

This Audio Guide is more of a conversation than a formal tour, so feel free to explore the exhibition at your own pace.

###

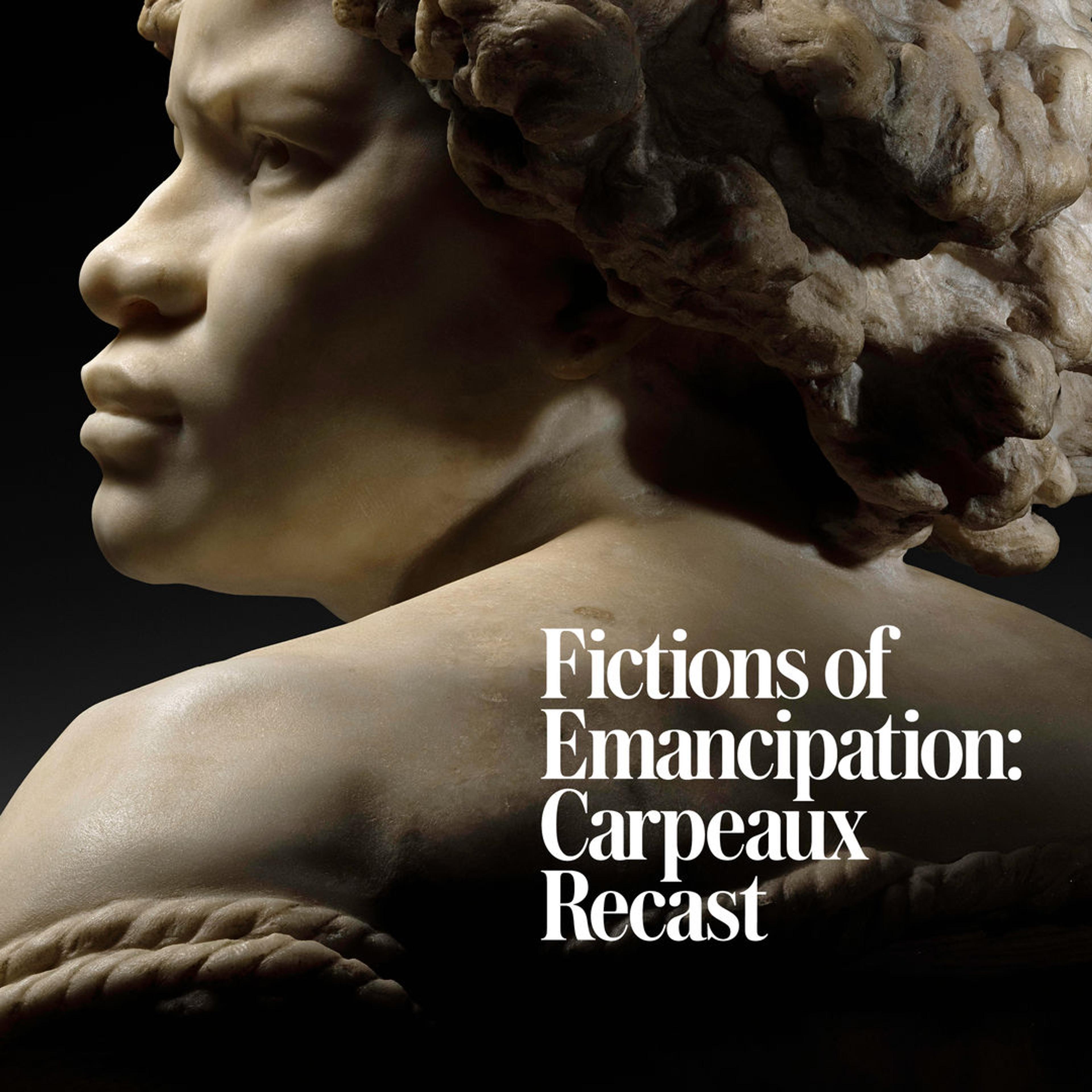

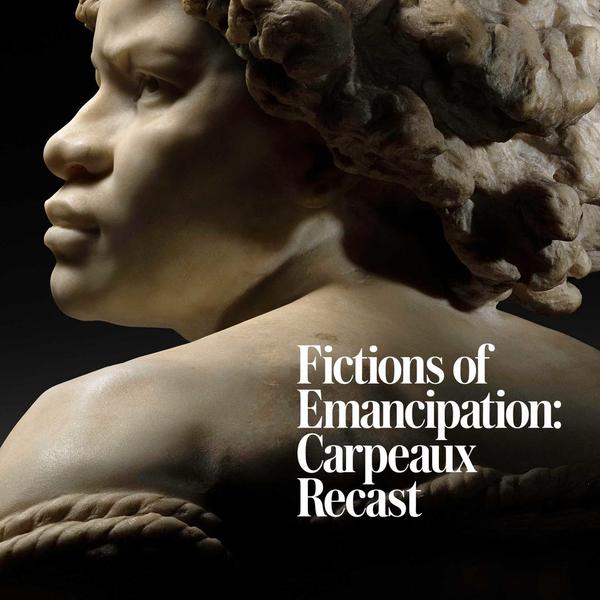

This exhibition centers around the artwork Why Born Enslaved! by the French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Created in 1868, twenty years after emancipation was achieved in the French Atlantic, the sculpture debuted in Paris a year later against the backdrop of European colonialism, imperialism, and the recent end of slavery in the United States. Carpeaux’s bust of a Black woman whose bare arms and torso are bound with rope is well known to Western audiences through the many versions produced during and after his lifetime. While the subject’s resisting pose, defiant expression, and accompanying inscription have long been interpreted as conveying a powerful antislavery message, the bust also visualizes longstanding European fantasies about the possession of and domination over Black people’s bodies.

The artworks presented in this gallery illuminate the aesthetic and colonialist influences embodied in Why Born Enslaved! Some works reveal the contradictions that emerge when abolition and emancipation are represented by the captive body. Others show how the depiction of the Black figure as an exoticized “type” was informed by the development of nineteenth-century ethnographic studies and France’s imperial ambitions in Africa. Together, these objects offer viewers an opportunity to reflect on the formative role visual art has played in shaping abiding misconceptions, or fictions, of racial difference, as well as the crucial role it still might play in dismantling them.

This project was realized through sustained collaboration between curator Elyse Nelson and guest curator Wendy S. Walters. Its planning was further enriched in consultation with numerous other contributors, and with the assistance of Rachel Hunter Himes; The Met gratefully acknowledges their participation. You are invited to join the conversation by sharing your reflections in the contemplation and response space nearby.

The exhibition is made possible by the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Foundation.

Additional support is provided by Allen R. Adler and Frances F. L. Beatty.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

531. Elizabeth Colomba on Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

Narrator: This is the sculpture "Why Born Enslaved!" by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux.

It’s a life-size bust, and she’s peering over her shoulder. Her curly hair is parted in the middle and flowing out in either direction.

The expression on her face is serious, defiant even. Her garment has been pulled off her shoulder, exposing her breast. Her twisting pose signals her resistance as she moves against the ropes that bind her arms and torso.

We don’t know the name of the Black model who posed for Carpeaux for this piece. But her presence in the artist’s studio must have had a profound impact all the same.

French Painter Elizabeth Colomba is ambivalent about Carpeaux’s sculpture.

Colomba: I have mixed feelings about the piece. I still think it's a beautiful piece as an art object. But I feel just because it um was at a time where maybe France was grasping with with their identity—you know, they had the revolution, the abolition. It’s a way to redefine who they are, the identity as you know male virility…and French. And whiteness. So, it's all that.

So, if you're going to use a piece of art that is going to be so, you know, represent figure Blackness, it was still linked to the idea of slavery and being chained, still perpetrating the same image and the same idea of: what is Blackness for that society.

Narrator: Colomba’s paintings reimagine new narratives for Black figures who have been either sidelined or left out of the history of Western art. She likes to portray Black people in ways Western artists of Carpeaux’s time did not: as free and equal.

Colomba: My practice is about representing Black figures, and Blackness, in different ways and in context where they’re not uh supposed to be. And I give them center stage and uh place where they possess the canvas, and they are the hero of their own story. So, that’s what why I like to portray, um, I'm going to call them success stories of historical characters that were into slavery—and that were able to escape slavery, and have a full life.

Narrator: Carpeaux was one of the greatest French sculptors of his time, widely praised for his ability to articulate the emotional depth of his subjects. In the 1860s, he received a number of large commissions.

Carpeaux designed a fountain depicting four figures of Africa, America, Asia, and Europe. The figure of Africa had a broken shackle around her ankle. Why Born Enslaved! is a separate bust Carpeaux made based off of the fountain design. For this piece, she is instead bound by rope.

Colomba: I see a woman with a furrowed brow… Great hair texture, great body, so very muscular… and the rope around her is like she's, you know, she's bound still.

Narrator: By 1868, when Carpeaux first modeled the bust, most Europeans had embraced the idea of abolition. But it had only been twenty years since France ended enslavement in its colonies in 1848. Many people, including Carpeaux, remembered a time when Black people were still legally considered property.

Colomba: It's not that long in between, right? It's very comfortable to see Black people still bound; because it seems like you still have control. There's still the fear of the image it gives you as the person who was the enslaver; meaning that you see somebody you hurt for generations, you can’t fathom the idea that they're not going to do something back.

Narrator: On the same platform, you can see a terracotta version of Why Born Enslaved! Displayed together, the marble and terracotta remind us that Carpeaux made many reproductions of the piece for sale.

Over the years, many have interpreted "Why Born Enslaved!" as a symbol of inclusivity and freedom— even as evidence of Carpeaux's commitment to the cause of abolition. But we know nothing about the artist's interest in abolition; it’s possible he had other motivations. At the time Carpeaux created the bust, French support for abolition was a point of nationalistic pride. For Carpeaux, creating a sculpture representing the horrors of enslavement some twenty years after emancipation was achieved in France boosted his profile as both an artist and a patriot.

Colomba: I think he wanted to denounce slavery.

And he used the tools he had: art and sculpting, to denounce something that he thought was horrific.

Which is interesting—to repossess the idea, or take the idea of slavery for himself.

And I think maybe because of the time it was France, politically, was in a difficult situation. Because obviously, they're losing their colonies. They may be losing power, economical power, it was a way to reaffirm their place in time as male and White and how they're fitting in this world. And that fight, to a certain degree, it’s like: it's our fight as well.

I’m torn between the idea of denouncing something, which was I think the intent of Carpeaux at the time— you see it obviously in the title—but at the end of the day, the image I'm seeing is a Black woman being bound.

This bust of this woman, we don't really know who she is, there's no name of the model. There's no story behind her. She's just this idea that conveys Carpeaux’s conscience and wanting to do the right thing. But it's still not doing the right thing, because it doesn't give her a place as a person.

###

Designs for Why Born Enslaved! were developed from Carpeaux’s studies for a full-length allegorical figure of Africa for a monumental fountain sculpture. Drawing on classical archetypes, the bust continues a visual tradition of captive or enslaved Black figures that had long populated European art. Carpeaux, who was celebrated for the animacy of his sculptures, imbues his subject with intense emotion. The works in this section reveal the artist’s creative process as he arrived at his final composition through a series of sketches of kneeling and bound captive figures featuring the Black model who posed for him.

The name of the woman who posed for Why Born Enslaved! is unknown, as was the case with most Black models working in Paris at the time. Yet her powerful presence in the artist’s studio undoubtedly contributed to the sculpture’s astonishing immediacy. Carpeaux’s portrayal bears a resemblance to Louise Kuling, a free American woman who was photographed in Paris as part of an ethnographic portrait series for France’s National Museum of Natural History in 1864, but this identification remains a speculation.

Louise Kuling, 1864. Jacques-Philippe Potteau (French, 1807–1876). Albumen print. Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris (SAP 155 [7] / 63). Image: Archives de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, déposées au Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

534. Fabienne Kanor on the Antislavery Medallion and Cologne Bottle

Narrator: There is more to this small piece than meets the eye. It’s a famous anti-slavery medallion by the artist Josiah Wedgwood, made in 1787. Measuring only around 3 centimeters, it depicts a kneeling Black man, wrists in chains, looking up with his hands clasped together in front of his face. The inscription reads: “Am I not a man and a brother?”

Like Wedgwood, many white artists in this period chose to depict the experience of formerly enslaved people by showing them in desperate need of help. Fabienne Kanor:

Kanor: I see a man who was supposed to be me, to be my ancestor, kneeling on the ground. He’s got his hands up, begging for mercy. Begging for White help. I see again, a man relegated to just an object. Because without the support of the White man, he cannot be free. So I see a prisoner. I see a White fantasy.

Narrator: Kanor is an artist and professor of French and Francophone studies at Penn State. But above all else, she considers herself an activist, seeking to share untold stories about womanhood, Blackness, identity and colonial history.

Kanor: I come from the French West Indies. My parents were born in Martinique. Coming from this special place, I feel particularly familiar with the kneeling Black figure on this medallion. Actually, I've never called it “anti-slavery medallion.” I've never seen it as an effective tool that contributed to the 18th century to restore the image of my enslaved ancestors—and help them to be free. Instead, I think that I view this image as a visual marker that shows the perpetuation of the myth of black inferiority.

Narrator: Kanor believes that images that depict Black people as powerless and victimized, like the one on this medallion, continue to have a negative impact.

Kanor: The figure of the good Black citizen, kneeling on the ground and asking for help, is really part of my family album. It is an image that has always had an impact on the behaviors of my family members.

My grandfather, his name is Papa Jerome, was born in Martinique several decades after the second abolition of slavery in the French West Indies.

Like his own father —like billions of post-colonized people—my father has internalized the stereotype alleging his inferiority. Like the Black figure on the Wedgwood medallion, he too has never got an answer to the 18th century question: “Am I not a man and a brother?”

Narrator: Black people had to surrender themselves to White people in order to be a part of their society. And even though Black people and the formerly enslaved were also part of the abolitionist movement, an object like this medallion was primarily made for White society.

It’s no surprise, then, that it didn’t truly capture the full Black experience.

Kanor: What shocks me is all these White artists thought they were showing the truth in representing the oppressed. But the truth is they didn't know anything about the people they represented. They only used them as arguments for the anti-slavery campaign.

Narrator: Including abolitionist imagery in everyday objects like this allowed people to position themselves as supporters of the abolitionist cause. These were often the only objects Europeans saw that had representations of Black people. As such, they carried a tremendous amount of cultural weight and importance.

Placed behind the anti-slavery medallion is a cut-glass cologne bottle from around 1830.

This bottle’s six-inch size belies the immense power of its imagery. A man in a similar stance as the figure depicted in Wedgwood’s anti-slavery medallion—kneeling, wrists in chains, begging for mercy—is encased in what Kanor views as much more than a simple decorative object.

Kanor: I see that man put in a cage. I see a prisoner. I see a man viewed as an object; as something, you use again and again and again. We know that the abolitionist had to popularize the figure of the slave to be freed. The main goal was to make these characters visible everywhere in public spaces, but also in the houses of White people. And it was a noble goal on the surface—We don't see the unfortunate slave anymore but an exotic, everyday object as shocking as it is useful and beautiful.

I asked myself for whose benefit was this object created? I'll assume that the White people who bought it and use it every morning felt happy about the purchase. they probably felt a certain satisfaction to participate in the anti-slavery movement. I assume that some must have said to themselves: “I fight against the enslavement of African people and my contribution is this bottle.”

Do we have the original names of all these Black persons who inspired the White artist? Do we know how old they were? Did they have spouses, brothers or children? Were they born in the New World? Or just arrived from Africa? And if they were from Africa, which country in Africa? Which village? Which neighborhood?

What did they leave behind them when they were enslaved? Who can answer my questions? Who can tell me exactly where these people were buried? Are they dead? Or was it just a White abolitionist fantasy?

###

- 534. Fabienne Kanor on the Antislavery Medallion and Cologne Bottle

- 535. Elizabeth Colomba on Edmonia Lewis

- 536. Fabienne Kanor on the French Revolutionary Playing Card

Playlist

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, abolitionist movements gained prominence across the Atlantic world following rebellions of enslaved populations in the British West Indies and Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti). Entrepreneurial artisans like Josiah Wedgwood created decorative objects featuring antislavery images and slogans for supporters of abolition to display at home or to wear on their bodies. These works, which circulated widely across Europe and the United States, often featured enslaved figures pleading for freedom in positions of submission, thus reinforcing the link between Blackness and subjugation.

Abolitionist imagery that represented Black personhood as inseparable from the ropes and chains of enslavement remained popular long after slavery had ended in England (1833), France (1794 and 1848), and the United States (1865). This theme is evident in commemorative works produced after emancipation, many of which retain attributes and gestures of Black subordination despite their celebrations of freedom. Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! belongs to the tradition of artworks that conflate Black personhood with depictions of captivity.

What is abolition?

Antebellum abolition philosophy started with the simple proposition that a person could not also be a chattel available for sale. At its most ambitious, it broached an ideal we are still striving toward: the radical premise of human equality. After the Civil War, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery and, the Supreme Court held, gave Congress the power to eradicate all remaining “badges and incidents of slavery.”

The modern movement to abolish the police and prisons argues that these institutions, too, fail to respect the humanity of people of color and that our reliance on them entrenches inequality in our society. Today’s abolitionists ask the provocative question: Where “badges and incidents of slavery” remain, can we say that the work is truly finished?

– Farah Peterson, Professor of Law, University of Chicago

Who narrates history?

Works of art reflect the perspectives of their makers, who, in the nineteenth-century Western tradition, were almost exclusively white men. Against all odds, Edmonia Lewis pursued her artistic career with unrelenting courage. The emancipated figures in Lewis’s Forever Free are imbued with power, dignity, and spirituality—human traits they share with their creator. Prior to sculpting this work, Lewis survived the loss of her parents in childhood, racially motivated false accusations of attempted murder while a student at Oberlin College, a trial for this alleged crime (for which she was exonerated), and a near-fatal beating by anonymous locals. None of these obstacles stalled her determination to sculpt—something almost no Black people and very few women were able to accomplish. Never looking back, she traveled to Boston to further her training and eventually settled in Europe, safely away from the brutality of Jim Crow America.

– Lisa Farrington, Associate Dean of Fine Arts, Howard University

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

533. Elizabeth Colomba on Allegories of Africa

Narrator: The bronze figure "Allegory of Africa" by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, dates to around 1863. A muscular African man reclines atop the skin of a lion—one of the many symbols Europeans associated with the continent.

After the abolition of slavery in France’s West Indian colonies, French imperialists turned their attention to economic interests in Africa. France, for one, had established a large colonial empire in Algeria, which was a source of great national pride for France.

This figure was part of a commemorative fountain showing French Admiral Bruat presiding over figures representing the parts of the world where he had helped establish French colonial presence: Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. The figure allegorizing Africa appears at the bottom of Bartholdi’s fountain—in a subordinate position. Representations of the four parts of the world like this one—and like the fountain that inspired "Why Born Enslaved!"—celebrated France’s dominance over non-European nations.

It gives painter Elizabeth Colomba pause to see this power dynamic:

Colomba: The feel that I have when I’m seeing this sculpture is: nothing can project the grandiosity of Africa. It's a continent with, first of all, so many identities, wealth and so much richness.

Narrator: Europe colonized regions of Africa, and other parts of the world, in order to extract natural resources. France justified its colonial exploits by characterizing them as “humanitarian missions” that sought to generously “civilize” cultures and peoples they found to be “primitive” and inferior to their own.

Art was used to normalize colonial relations and establish notions of European cultural superiority.

Now look directly to the left of Bartholdi’s figure to see a porcelain group representing the four parts of the world.

It was made in the 1780s, almost a century earlier than "Why Born Enslaved!" The figure of Africa stands next to a lion, carrying a cornucopia of fruit. Many of the features—especially the headpiece resembling the trunk of an elephant— appealed to European notions of African exoticism.

Colomba: There’s nobody behind Africa, but just the idea of Africa. So, meaning: that's why there's a headdress with an elephant trunk. And that's why you have this kind of weird animal in the back, which is, you know again, meant to be a lion, but come on.

Narrator: Allegorical images of the four continents have been part of European iconography since the Renaissance. Each continent was personified as a female figure, dressed up and holding accessories that Europeans associated with that part of the world. While the theme first predominated in print form, it later appeared in ornamental objects like this one, which played a symbolic role for Europeans who displayed them in their homes.

Colomba: People who possess this sculpture thought that they fully understood what Africa was by having this at home…or having this around them thinking that “this is Africa,” absolutely, and felt very well about it. You know, you're cultured, you're open-minded.

Narrator: As France expanded its empire into this part of the world, objects representing Africa became popular as decorative fixtures, representing the promises of wealth and resources that colonialism would bring.

###

Carpeaux created Why Born Enslaved! while working on The Four Parts of the World Supporting the Celestial Globe, a monumental fountain sculpture representing Africa as a female figure alongside Europe, Asia, and America. From the Renaissance onward, such personifications of the continents offered viewers a Eurocentric vision of empire. Early examples circulated widely in prints and the decorative arts, asserting the presumed supremacy of European civilization through symbols that represented the other continents as bountiful regions available for Western cultivation.

In the nineteenth century, France expanded its empire into North Africa and Southeast Asia and enlisted new forms of coercive labor in the West Indies following the abolition of slavery. A new technique for ordering the world emerged: ethnography attempted to classify human “types” via physical characteristics, which were presented as evidence of differing intelligences and abilities. This pseudoscience was used as justification for maintaining a racialized hierarchy at home and in the colonies. Physical traits also served as a shorthand for categories of racial difference in the work of artists like Carpeaux, whose Why Born Enslaved! reflected the moral currency that abolition lent to French imperial power.

Fountain of the Observatory, featuring The Four Parts of the World Supporting the Celestial Sphere, 1867–74. Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (French, 1827–1875) and Emanuel Frémiet (French, 1824–1910). Bronze. Avenue de l’Observatoire, Paris. Photo: Steve Cadman

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

532. Delphine Diallo on Charles Cordier

Narrator: Nineteenth-century sculptor Charles Cordier is a key player in Western art's portrayal of Black women. Sculpting from life, Cordier made one of his most famous works of the period, "Woman from the French Colonies." The artist’s descendants have suggested that the same woman who posed for this bust also modeled for Carpeaux’s "Why Born Enslaved!"

Cordier’s sculpture, in bronze and Algerian marble, was widely celebrated for its technical intricacies and detailed representation— including the figure’s skin color, facial features, and hair texture. She is draped in colorful marble and luxurious jewelry with gemstones. She wears a headpiece and a flower in her hair.

For photographer and visual artist Delphine Diallo, this work displays inaccurate stereotypes of Black figures that are common in the works of European artists.

Diallo: I'm French-Senegalese, and I'm born and raised in Paris. And I faced those sculptures very young. From the beginning, even that young, I saw the stereotype; And an aesthetic where we have to find this Black woman with a very exotic hair, headwrap, and like even the tone of their skin color. So, I was always aware of the stereotype of the work.

I knew that there was uh that was an interpretation that was not really based on reality. My work is about creating new archetypes for women, to feel empowered, to feel strong. I have this obsession with creating a legacy for a new vision for Black women.

How can I create the space for a Black woman in front of my lens, to make her alive and herself—beyond being beautiful, having a certain type of stereotype with braids, or headpieces, or anything that people can relate to stereotype?

Narrator: Because Cordier traveled to Egypt and Algeria, many Europeans believed his busts of African people were true-to-life. But he often combined features from different subjects he encountered to create his idealized version of the African figure.

Cordier believed he was creating a new standard of beauty for the previously enslaved. At the time he commented: “My art incorporated the reality of a whole new subject: the revolt against slavery and the birth of anthropology.”

Many of the bust’s features draw on the classical European tradition—from her serene expression to the side-swept draping of her garment. By appointing the bust with these features, Cordier was trying to use the language of European beauty and aesthetics to define something that couldn't possibly be adequately captured by it—the beauty of Africa and its people.

Diallo: So, the nipple is present. So, I'm questioning this, you know? And some people say: “No, it's not sexualizing.” I have these questions: why through history do you have to see the nipple behind the shear of a woman?

So those sculptures of Cordier… I don't think he was interested to know the subject that well. He was probably studying it like in ethnography, traveling the world.

So, we’re dealing again with a pretentious male gaze. Empiric vision on someone.

For me, there is still a lack of understanding of the subject.

Narrator: Although Cordier worked with real-life models, he portrayed them as racialized types, knowing that doing so would appeal to European audiences.

Diallo: It was like a trophy. Yeah. So, I see this more like a trophy, of the most beautiful interpretation of a world that they never understood.

###

Black figures appeared regularly in nineteenth-century European painting and sculpture. While these representations were often naturalistic, they rarely portrayed individuals. More often, artists depicted Black figures as racialized “types” intended to stand in for ideas, peoples, or entire continents. Such works of art were closely associated with the growing field of ethnography, which sought to classify humans according to physical appearance and thus gave birth to the fiction of racial categories.

Yet real people posed for the artists who created these images. Some of the models who sat for the works in this section were recent immigrants to Paris from North Africa or from the French colonies in the West Indies. Others were people whom artists encountered while traveling abroad. The names and biographies of these individuals were disregarded or lost, their likenesses recast into exoticized symbols. Similarly, Carpeaux used the likeness of the free Black woman who modeled for him to represent enslavement.

What is representation?

As a child growing up in France, I watched the television series La Noiraude, named after its protagonist, a black cow, who was always in trouble. Her whole life was a failure. She called her vet every day to complain and to tell him how unlucky and cursed she constantly felt. That story did not take place a long time ago in a kingdom far, far away. It happened every night, on the television screen. Like millions of French people, I listened to the black cow’s laments, and I laughed. I laughed at her. I laughed to tears until some white schoolmates decided to baptize me “La Noiraude.” And then the TV screen became a mirror. And then I became La Noiraude. And then I became a problem. Representation is not something to be taken lightly. When it is false, it is heavy, like shackles or a rope around the neck. It stops us from flying toward our authentic selves.

– Dr. Fabienne Kanor, Writer, Filmmaker, Performer, and Assistant Professor, Pennsylvania State University

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Marble and bronze versions of Why Born Enslaved! debuted in Paris in 1869, the same year Carpeaux established a commercial enterprise dedicated to producing replicas of his most famous sculptures. The reproduction of the bust in multiple media at varying price points enabled the artist to market his sculpture to a broad range of consumers, from the Emperor and Empress of France, who owned a version in bronze, to members of the middle class. As a commodity, this bust of an enslaved woman symbolically echoed the objectification of people of African descent, embodying a practice the sculpture was ostensibly designed to critique.

Replicas of the sculpture continue to be produced today, from editions in resin to luxury candles in wax. Its appearance in a recent marketing campaign for Beyoncé’s Adidas x Ivy Park clothing line further attests to its prevalence in popular culture. Yet its reproduction has also opened the door for contemporary artists to intercede in this continuous cycle of commodification by reimagining the bust. Kehinde Wiley’s and Kara Walker’s works on view here recast and transfigure the sculpture to confront and defy—but not resolve—the hierarchies of race underlying Carpeaux’s creation.

What is the legacy of the Black figure in Western art?

We gain insight into the nineteenth century when we see the period’s representation, commodification, and fetishization of Black females and the disproportionate amount of attention aimed at their bodies. These representations articulated notions of a French national identity while affirming the concept of the “other.” Carpeaux’s interpretation of freedom, of the injustice of enslavement, remains embodied in a bound woman. Despite his best intentions, as a white male artist Carpeaux is only able to convey his perception of a world about which he has only an idea. It’s crucial to contextualize his imagery, for it affects our collective psyche. If we don’t, the bust allows us to accept that the Black female body can still be collected and consumed, be gazed at, desired, despised, dissected, and distorted by all. To quote James Baldwin: “You have to impose . . . you have to decide who you are, and force the world to deal with you, not with its idea of you.”

– Elizabeth Colomba, Artist

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.