Much of what we know about the interconnectivity of the Mediterranean world in the first millennium B.C. relies on archaeological discoveries of the past two centuries. Indeed, behind all of the objects on display in Assyria to Iberia lie modern stories of discovery and recovery. The city of Babylon in southern Iraq, once reduced almost to a figment of modern imagination, was revealed by excavations beginning in the nineteenth century. The Assyrian empire, once unknown outside the Bible, was brought to light by excavations in northern Iraq beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. And the cities of the Phoenician homeland in modern Lebanon were explored in the mid-nineteenth century and then excavated beginning in the 1920s. Archaeological discovery has also played an important role in our understanding of the origins of the alphabet, which was invented in the early second millennium B.C. and spread across the Mediterranean world in the first millennium B.C.

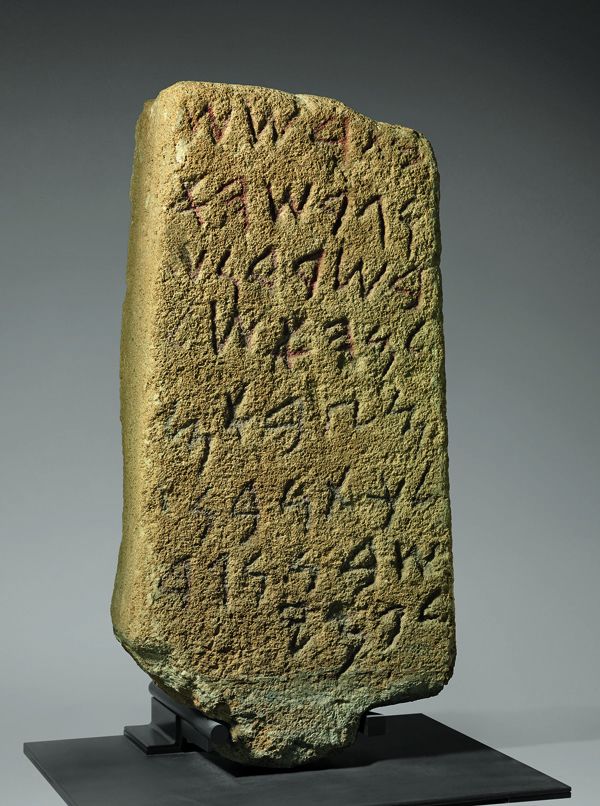

This sandstone stele with an eight line alphabetic inscription (read right to left) was discovered in 1773 in the wall of a vineyard on the island of Sardinia, near the ancient coastal site of Nora. The monument is one of the most ancient Phoenician inscriptions known from the western Mediterranean, and its text still remains imperfectly understood. Sardinia, Cagliari, Pula. Phoenician, ca. 850–740 B.C. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Cagliari (5998).

Just over a hundred years ago, at the outset of the twentieth century, little was known about the origin of our modern alphabet. Multiple alphabets, including the Greek and Phoenician alphabets, were used in the first millennium B.C. Archaeological evidence for the Phoenician alphabet (deciphered as early as the mid-eighteenth century) appears across the Mediterranean, suggesting the widespread presence of Phoenician merchants and colonists. The Greek and Phoenician alphabets were thought to be somehow related, because both the forms and names of many signs in the two alphabets were similar. Since the names of the Phoenician letters (known especially from later Hebrew sources) correspond to real words—for example, the Hebrew word for the letter ‘ (pronounced ‘ayin) is the same as the Hebrew word for "eye" (‘ayin)—some scholars also suggested that the letters of the alphabet would have been originally pictographic, but there was no consensus on how or where these pictographic signs might have been invented. Books written at the turn of the last century, such as Isaac Taylor's The Alphabet: An Account of the Origin and Development of Letters (1883) and Edward Clodd's The Story of the Alphabet (1900), speculated about the origin of our modern alphabet and the relationship between the various alphabets.

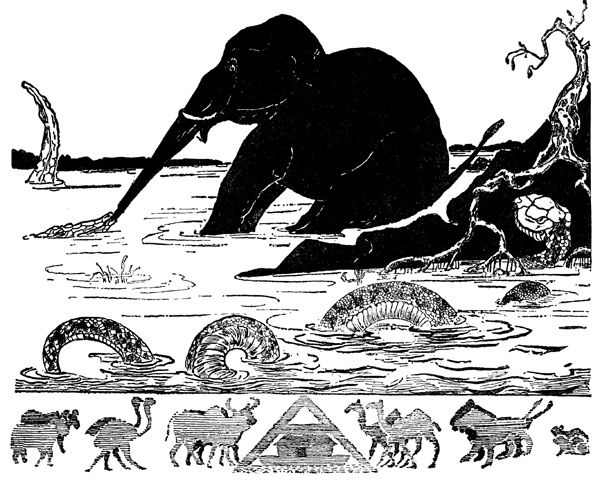

One of Kipling's original illustrations. Created for the story "The Elephant's Child," this image was also used for the cover of the 1902 edition of Just So Stories.

During this time of speculation about the origin of the alphabet, the English novelist and children's author Rudyard Kipling wrote "How the Alphabet was Made," a fictional account of the alphabet's invention. Published in 1902 as part of the Just So Stories, this children's tale describes how a "Primitive" cave-dwelling Neolithic girl, Taffy, and her father, Tegumai, use various strategies to invent "noise pictures." Kipling was not a scholar of ancient writing systems or languages, but his story reflects the popularity of the topic of alphabet origins at the beginning of the twentieth century. Soon, far more would be known about how the alphabet was actually invented, and the world in which it originated.

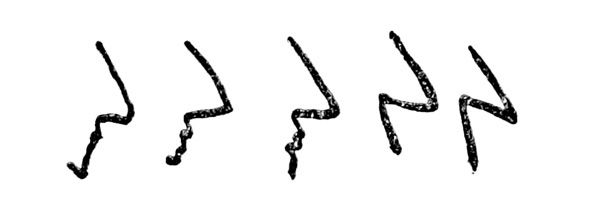

Kipling imagined the letter N as an abstract nose.

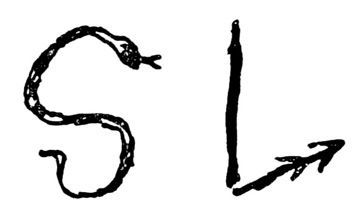

The letters S and L come from drawings of a snake and a broken arrow.

In Kipling's tale, Taffy and her father Tegumai are fishing for carp one day when Taffy has the idea to write down sounds on bark using a shark's tooth. Together, she and her father use numerous strategies to invent the letters of the alphabet. Sometimes, mouth shapes used to make particular sounds are represented in the drawings of letters, as with the egg shape used for the letter O. Pictures also represent the quality of a sound, such as the "nasty, nosy noise" that lies behind the drawing of a nose for N. The picture for S is a hissing snake. L is drawn as a broken arrow because the word "las" in the imaginary Tegumai language means "broken" and begins with that sound. As they draw the "noise pictures" over and over again, the egg-shaped O, the nose, the snake, the broken arrow, and the other pictures look more and more like our modern letters. After two days of work, Taffy and Tegumai create a full set of "noise pictures," an invention that Kipling calls the "great secret of the world." Created "thousands and thousands and thousands" of year ago, Taffy and Tegumai's alphabet is lost and then reappears "after Hieroglyphics and Demotics, and Nilotics, and Cryptics, and Cufics, and Runics, and Dorics, and Ionics, and all sorts of other ricks and tricks."

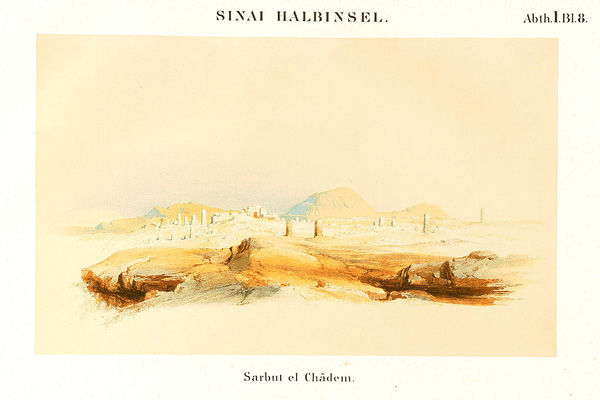

Nineteenth-century illustration of Serabit el-Khadim. From C. R. Lepsius, Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien (1849–1859), Abt. 1: Topographie und Architectur.

Just two years after the publication of Kipling's Just So Stories, the English archaeologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie made a discovery in Egypt's Sinai Peninsula that would begin to solve the question of the alphabet's origin. At Serabit el-Khadim, the site of an Egyptian turquoise mine used extensively during the second millennium B.C., Petrie found numerous inscriptions, both near the mine and at a local temple of the goddess Hathor. Although the majority of the inscriptions were written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, several undecipherable writings were also discovered. The pictographic signs of these inscriptions were not like those written with the hieroglyphs and could not be interpreted using the ancient Egyptian language. Several scholars, including Petrie himself, suggested that these pictograms might represent some form of alphabetic writing, but it was the English Egyptologist, Sir Alan Henderson Gardiner, who identified the Sinai writings as the hypothesized, but previously unknown, ancestor of the Phoenician (and Greek) alphabet.

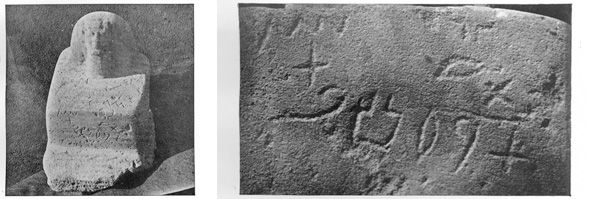

Photograph and detail of a statue found at Serabit el-Khadim with a pictographic alphabetic inscription. From Petrie's publication of his excavations in the Sinai Peninsula, Researches in Sinai (1906), plates 138 and 139

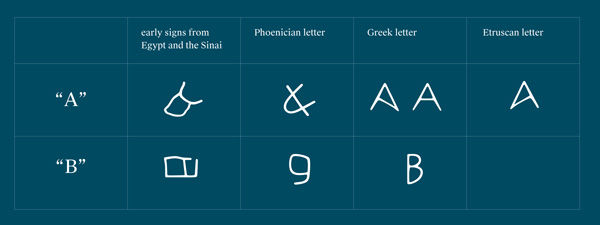

To decipher the Sinai signs Gardiner relied heavily on the names of the letters (known from later sources) and the principle of acrophony. Acrophony is the use of a word to name or represent the letter with which it begins (as in "A is for apple"). Unlike previous scholars working on the origins of the alphabet, Gardiner asserted that the West Semitic letter names must have been part and parcel of the invention of the alphabet. The head of an ox (Hebrew ’elep; Phoenician ’lp), therefore, must represent the consonant ’ (later adapted to write the vowel A by the Greeks), and the variously shaped rectangles used for the letter B were floor plans of a house (Hebrew bayit; Phoenician bt). This meant that the alphabet would have been created by speakers of a West Semitic language, probably the Levantine ancestors of the Phoenicians.

Chart showing the ancient development of our modern letters A and B.

Dated by Gardiner and others to the early second millennium B.C., these pictographic signs are the ancestors of our modern letters. The names of the first two signs (Hebrew ’ālep and bêt; Greek alpha and beta) form the basis of our modern word "alphabet" (Greek alphabētos; Latin alphabetum), and were transmitted, with the rest of the letters, from the Phoenicians to the Greeks and Etruscans, and then to the Romans. While Gardiner's proposal was debated for decades, the recent discovery of additional alphabetic writings on the cliffs alongside a road through the desert at Wadi el-Hol in Egypt have added credence to his idea that the alphabet was invented in the early part of the second millennium B.C. by Semitic speakers who drew upon Egyptian hieroglyphic (and hieratic) writing.

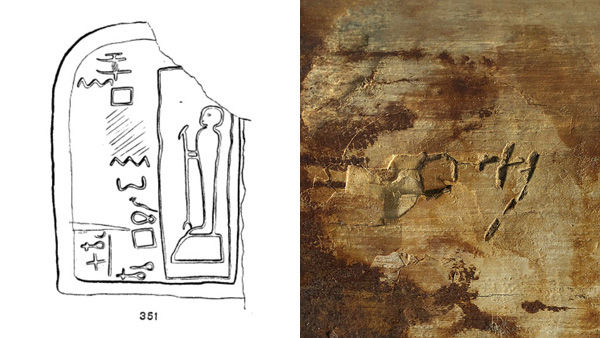

Left: Gardiner's drawing of a stele from Serabit el-Khadim showing the letter M in two places. Right: A later Phoenician form of the letter M as seen in this detail of an inscribed ivory tusk from a shipwreck at Bajo de la Campana, Spain. The short inscription (m’, read right to left) may be an abbreviated personal name, possibly Melqartsama'. Manga del Mar Menor, Bajo de la Campana shipwreck area. 7th–6th century B.C. Museo Nacional de Arqueología Subacuática, Cartagena (1540)

Unlike Kipling's imaginary alphabet, which used multiple strategies in the creation of signs, the "A for Apple" principle used to create the signs found at Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi el-Hol was applied to all of the letters. So whereas in Kipling's story the "rough and edgy" sound of "rrrrrrr"—which sounds like a shark-tooth saw cutting through wood—was represented by a shark tooth, in the Sinai and Egypt alphabetic writings the picture for R depicts the head (Hebrew rō(’)š; Phoenician rš) of a man. And instead of a closed mouth making the "mmm" sound, the squiggly letter M actually stands for water (Hebrew mayim; Phoenician mym). Yet in the history of alphabetic writing, as in Kipling's story, pictures become more abstract, increasingly resembling our modern letters.

Left: Kipling imagined the letter A as an abstract representation of "a carp-fish's mouth wide-open." Right: Gardiner's drawing of an inscription from Serabit el-Khadim showing the letter represented as an ox head in the upper right.

In the story of Taffy and Tegumai, father and daughter create signs that are drawn from their world: the letter A, for example, is an abstract representation of a carp's mouth. Similarly, the Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi-el Hol letters are thought to reflect the experience of Semitic-speaking peoples living in Egypt in the early centuries of the second millennium B.C. In this case, the ox-head letter ’ (later, A) may reflect the importance of cattle, documented elsewhere by the presence of bovine bones in contemporary Levantine burials. Many of the Sinai and Egypt letters are representations of weaponry and architectural elements, possible further clues to the values and lifestyles of the people who invented the alphabet.

One of several stone vessels inscribed with the names of Egyptian kings found at a Phoenician necropolis where they were used as cinerary urns. This veined gray marble vessel is inscribed in several places in Egyptian hieroglyphs by the Hyksos king Apophis, including the rim. Almuñécar, Laurita necropolis. 8th century B.C. context, Egyptian manufacture, Dynasty 15, reign of Apophis (1581–1541 B.C.). Museo Arqueológico de Almuñécar, Almuñécar (M.A. 00018).

Far from originating in the local carp-fishing hole of a Neolithic camp, the alphabet was created in an interconnected world. Interaction between the West Semitic speaking peoples of the Levant and the Egyptians was lively and extensive in the early second millennium B.C. Egyptian iconography and symbols can be found in the arts of the Levant, and Levantine peoples traveled and lived in Egypt. During the middle of the second millennium B.C. an Asiatic people known as the Hyksos even ruled northern Egypt. Although these rulers were foreign kings, their inscriptions appear in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Left: Basalt funerary stele of a priest with an alphabetic inscription in Aramaic, found near Aleppo. The signs and language of Aramaic inscriptions are closely related to Phoenician. Neirab. Syro-Hittite, ca. 700 B.C. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités Orientales (AO 3026). © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY, photograph by Franck Raux. Center and right: Bronze statuette of the goddess Astarte from Spain and detail of the Phoenician inscription on the footstool. El Carambolo (?), Camas, Seville. Phoenician, 8th–7th century B.C. Museo Arqueológico de Sevilla, Seville (11.136).

In the first millennium B.C., the now abstract signs of the alphabet were used by Phoenicians and, increasingly, other peoples. Monuments from the Levant and southeastern Turkey are regularly inscribed with alphabetic writing. In the east, alphabetic writing was used alongside the historic and complex cuneiform writing system. And Phoenician merchants left behind alphabetic inscriptions across the Mediterranean, as far west as Spain. The alphabet used by the Phoenicians was adopted and adapted by the Greeks and Etruscans.

Crystalline sandstone bust of the Egyptian king Osorkon I with an alphabetic inscription of Elibaal, king of Byblos. Byblos. 9th century B.C. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités Orientales (AO 9502). © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY, photograph by Cristian Jean / Jean Schormans

Even as the alphabet spread across the Mediterranean world, memory of the pictographic origins of the alphabet seems to have been lost. Phoenician inscriptions on Egyptian objects show how abstract the signs of the alphabet had become when compared to the pictographic hieroglyphic signs. The Greeks were conscious of the alphabet's Phoenician roots, and referred to their letters as phoïnikeia grammata (Phoenician letters), but the earliest pictographic history of the alphabet was left for modern discovery.