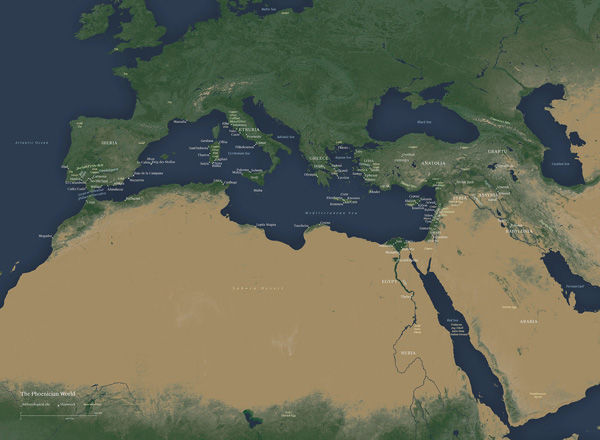

In countless ways, Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age represents the world of the Phoenicians and the world made possible by Phoenician expansion. Sailing westward from their homeland on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, the Phoenicians traded with indigenous peoples and established colonies as far west as the Atlantic coasts of Spain and Morocco, past the Straits of Gibraltar. The spread of these maritime people parallels—and can be often understood as the impetus behind—the movement of art objects and the exchange of materials and motifs across the Mediterranean in the first half of the first millennium

Map showing the settlements across the Mediterranean in the earlier half of the first millennium B.C. Colonization of the western Mediterranean was led by the Phoenicians. See a larger version of the map.

Yet for all that the Phoenicians contributed to the crosscurrents of interaction celebrated in the exhibition, relatively little is known about the lives and livelihoods of Phoenician sailors. The types of documentation known to us from famous European sailing ventures—like logbooks, passenger lists, journals of crew members, maps, and ship plans—either did not exist in antiquity or have not survived to the present day. And while the well-known biblical story of Jonah begins on the deck of a Phoenician ship bound for Tarshish (possibly to be identified as modern Huelva, in Spain) and describes the sailors crying out to their gods at the onset of a violent storm, the scene quickly shifts overboard to the belly of the whale.

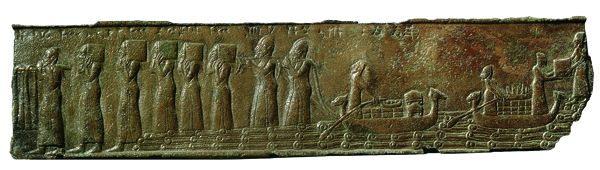

Above: Phoenician ships on fragments from a bronze band. Balawat. Neo-Assyrian, ca. 848 b.c. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Museum Purchase, 1949 (54.2335a). Below: Musée de Louvre, Paris, Départment des Antiquités Orientales, Bequest, Gustave Schlumberger, 1931 (AO 14038).

Contemporary representations of Phoenicians in Assyrian art depict a variety of Phoenician vessels. High prow and stern boats with horse heads appear on the embossed bronze band of a gate at Balawat featured in the exhibition. Two adjoining bronze fragments of the band depict Phoenician ships from Tyre and Sidon delivering tribute, including metal ingots and what appear to be elephant tusks, to the Assyrian king. Later depictions on the walls of Khorsabad and Nineveh show horse-headed ships dragging cedar logs, round-hulled merchant ships, and warships with long, pointed prows.

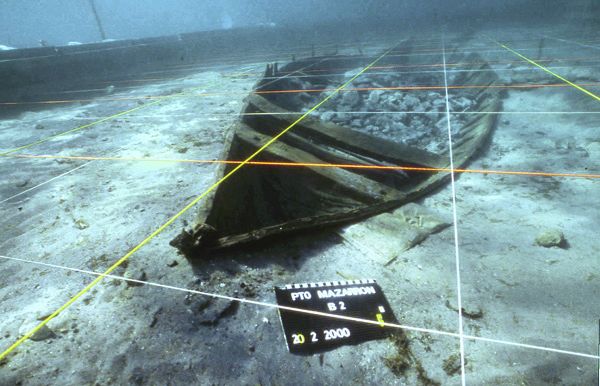

For decades, these Assyrian representations were the main source of knowledge for Phoenician ships. Thanks to the advent of scuba diving and the subsequent development of underwater archaeology, a new source for the study of Phoenician vessels and trade emerged in the late twentieth century a.d.: shipwrecks. Sunken Phoenician ships have been discovered from the deep Mediterranean waters near Ashkelon, in modern-day Israel, to the Spanish shoreline. Found with remains of cargoes, shipware, and sometimes parts of the wooden ships themselves, these wrecks have added greatly to our knowledge of Phoenician sailing.

A Phoenician shipwreck at Mazarrón, off the coast of Spain, unusually preserved much of the ship itself. Some of the objects found in the Mazarrón wreck are included in Assyria to Iberia. © Pedro Ortiz and Iván Negueruela.

Last month, a Sunday at the Met program celebrated and explored the impact of underwater archaeology on our knowledge of ancient sailing with talks from two different perspectives, one from the Mediterranean seabed and the other from the crest of the waves. Speaking from their vistas as an archaeologist and as the captain of a re-created Phoenician ship, respectively, Mark Polzer and Philip Beale helped bring to life the world of the seafaring Phoenicians.

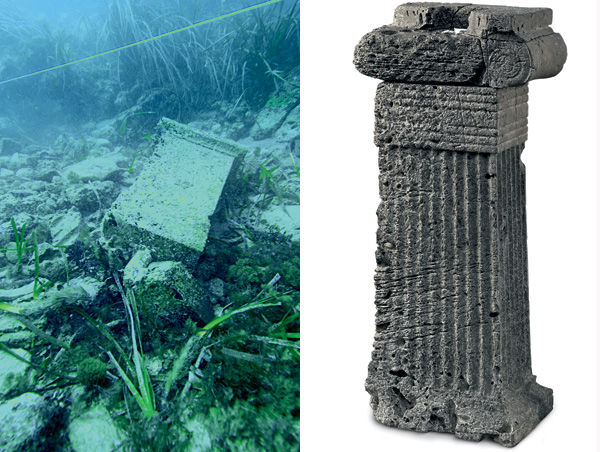

As a maritime archaeologist, Mark Polzer ventures to the depths of the Mediterranean Sea in order to study how ships and sailors helped connect the ancient world. His most recent excavation of a ship that wrecked on the submerged outcropping of Bajo de la Campana off the coast of Spain offers new data on Phoenician trade in the west from the heyday of Phoenician expansion in the seventh century b.c. One of the surprise finds from the excavation is the stone altar that is on view in Assyria to Iberia.

Left: An altar was found beneath a boulder on the first day of diving during the 2008 season. © Institute of Nautical Archaeology, College Station, Texas. Photograph by Heather Brown, 2008. Right: The fluted volute-capital altar. Manga del Mar Menor, Bajo de la Campana shipwreck area. Phoenician, 7th–6th century b.c. Museo Nacional de Arqueología Subacuática, Cartagena (BC08-342)

According to Polzer:

One of the puzzling aspects of this shipwreck excavation was that we found very few objects that can be categorized as shipboard equipment or personal effects of the crew. Whetstones and pan-balance weights are best interpreted as belonging to a craftsman or merchant on board the vessel, and the charring around the nozzles of the only intact lamp we recovered indicates that it was used aboard the ship. But there is little else that speaks to the Phoenician sailors themselves. The one object that might is the stone altar. Although I remain uncertain as to whether this altar was for use aboard the ship or was part of its cargo, it certainly does remind us that the lives and livelihood of Phoenician and other ancient sailors were perilous and full of superstitions. Altars and other devices for offering sacrifice or libations have been found on a number of ancient shipwrecks, and dedications by sailors at sanctuaries or temples, typically located near harbors or prominent coastal features, are common. If the altar from Bajo de la Campana did indeed belong to the ship, its crew would have used it to make the appropriate sacrificial offering to their patron deity for a safe and successful journey. Tragically, in this case, their pleas fell on deaf ears.

Another one of the highlight finds of the excavation was the discovery of ivory tusks, known from previous decades when divers visited the site, but excavated in astonishing numbers by Polzer and his team. Today, more than fifty tusks are known, two of which are included in the exhibition. While these tusks appear to have been traded as raw materials, as in the depiction on the Balawat Gate, some of the tusks are inscribed with the names of individuals. Polzer believes that the inscriptions (including one that reads "Bless Eshmunkhalots!") classify the objects as votives—objects given to deities by individuals to maintain the god or goddess's favor—and that their appearance on board the ship may be the result of underhanded dealings by a sanctuary priest.

Archaeologists Mark Polzer and Juan Pinedo with two ivory tusks. © Institute of Nautical Archaeology, College Station, Texas. Photograph by Patrick Baker, 2010.

Left: Ivory tusk with an inscribed Phoenician name. Manga del Mar Menor, Bajo de la Campana shipwreck area. Phoenician, 7th–6th century b.c. Museo Nacional de Arqueología Subacuática, Cartagena (1540). Right: Detail of the inscribed name.

For Polzer, the most remarkable aspect of the Bajo excavation was the breadth of objects and material types originating in both Spain and the wider Mediterranean region and beyond that were recovered, including raw materials, produced goods, and luxury items. These objects—sourced and produced across Spain, imported from the central and eastern Mediterranean, and, in the case of the raw amber, originating in the Baltic Sea region—represent the extent of trade networks commanded by the Phoenicians in the late seventh century b.c. The mix of raw materials and luxury objects attests to the diverse trading relations maintained by the seafaring merchants.

The Phoenicia, a replica Phoenician ship. © Jennie Hill

Philip Beale, a lifelong sailor and the leader of the project called The Phoenician Ship Expedition, spoke about commissioning and navigating a replica Phoenician ship. The Phoenicia was built using knowledge of construction techniques from discovered wrecks. The hull was made sturdy by using tenons to join planks together and then drilling holes and hammering pegs through the joints (pegged mortise-and-tenon joinery), after which the ribs of the ship were fit in. Some elements, like the horse-headed prow, were included on the basis of ancient images of Phoenician ships like those found on the Assyrian reliefs. In 2008–2010, Beale and his team sailed the Phoenicia more than twenty thousand miles around Africa, demonstrating the robust construction of Phoenician ships. The expedition also highlighted the size of the crew required to operate an ancient vessel: eight strong people were needed to lower and raise the sails, and the ship's anchor weighed more than 600 pounds.

Concealed for thousands of years by the Mediterranean Sea, wrecks of Phoenician ships are providing new vistas not only of the ships themselves but also of the lives and livelihood of Phoenician sailors. The variety of traded raw materials and luxury goods found among the wreckage of the ship at Bajo de la Campana and the skills and strength required to build and navigate a ship across the Mediterranean, as demonstrated by the Phoenicia, reminds us why the Phoenicians were remembered as the "princes of the sea" (Ezekiel 26:16). Diving beneath the waves or sailing across the breakers, we find evidence of the Phoenician mastery of the Mediterranean and their outstanding contribution to the crosscurrents of interaction at the dawn of the Classical Age.