In her seminal essay "Notes on 'Camp,'" published in 1964, Susan Sontag stated, "To talk about Camp . . . is to betray it." While an elusive concept, camp can be found in most forms of artistic expression, revealing itself through an aesthetic of deliberate stylization. As a site of the playful dynamics between high art and popular culture, fashion is one of the most enduring conduits of the camp sensibility. Through color, prints, patterns, materials, silhouettes, and embellishments, fashion both embraces and expresses such camp modes of representation as irony, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration.

Before Sontag's treatise, camp—as she asserted—was "something of a private code, a badge of identity . . . among small urban cliques." Her essay changed this irrevocably, catapulting camp into the mainstream, where it has remained ever since. There are periods, however, including the 1960s, the 1980s, and the era in which we live now, when camp comes to the fore as the defining aesthetic of the times. It is no coincidence that camp resurfaces during moments of social, political, and economic instability—when society is polarized—because, despite its mainstreaming, it has never lost its power to subvert and to challenge the status quo.

Through her "Notes," Sontag provided us with a grammar to analyze camp. That language is employed throughout the exhibition, which is divided into two sections. The first examines camp's origins, and the second explores the camp sensibility as it is reflected in fashion. It is a truism that the only point of agreement about camp is that there is no agreement, and this exhibition might raise more questions than it answers: "Is camp gay?" "Is camp political?" And, ultimately, "What is camp?" However, a point of growing consensus is the centrality of camp not only to fashion but to culture in general.

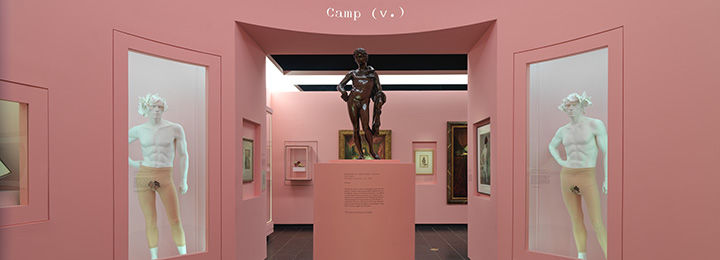

The "beau ideal" is an early nineteenth-century concept that describes the perfect model of male beauty, often exemplified by classical statuary. The contrapposto stance of these sculptures—characterized by the counterpoise of the shoulders, which turn away from the hip, and the resting of the weight on the back foot—helps to showcase not only symmetrical musculature and an idealized youthful athleticism but also a noble character, embodying the humanist ideal of an even temper. The arm akimbo, bent from the hip with the hand turned back, signals both power and relaxation.

Sculptures of Hermes, Ganymede, and Antinous (see the bronze on view here) are most often cited as examples of the beau ideal. Since the Renaissance, they have also come to be associated with male homosexuality, and as such have been endowed with the camp trace. Antinous, the young lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian (second century A.D.), was deified after his death and became a Hellenic idol of homoeroticism. From the seventeenth century onward, he served as a personification of male-to-male love. In the twentieth century, his contrapposto stance with arm akimbo became synonymous with the camp pose known as "the teapot."

As an aesthetic category, the word "camp" derives from the French se camper—"to flaunt" or "to posture." The first known usage of se camper appears in Molière's 1671 play The Impostures of Scapin, a three-act comedy of intrigue. In one scene, the crafty Scapin persuades a fellow servant to disguise himself as a violent mercenary and "camp it up" in order to deceive the family patriarch into parting with a large sum of money: "Camp about on one leg. Put your hand on your hip. Wear a furious look. Strut about like a drama king."

In the context of Molière's comedy, se camper alludes both to the bent pose of Scaramouche, the archetypical "crooked" servant of the commedia dell'arte, and to the regal pose of Louis XIV (the "drama king". In the portrait by Hyacinthe Rigaud on view here, the monarch is depicted in the pose Scapin parodies: arm akimbo and leg extended in a contrapposto stance that recalls classical statuary.

With its grand fetes and lavish entertainments, Louis XIV's Versailles has been designated—retroactively—as an idealized "camp Eden." Contributing to this image are the homosexual and cross-dressing practices of the king's younger brother, Philippe I, duc d'Orléans, known as "Monsieur." In terms of his "camp" identity, Philippe is eclipsed only by the androgynous nobleman known as the Chevalier d'Eon, a member of the King's Secret—a covert department engaged in espionage. Although he spent his first forty-nine years as a man, d'Eon lived the remaining thirty-three as a woman, after claiming he was assigned female at birth.

In the nineteenth century, the word "camp" acquired distinctive homosexual connotations. It emerged as part of a covert, coded language among gay men that had its roots in the homosexual or "molly" subcultures of eighteenth-century England. Known colloquially as "the female dialect," this language was a furtive, topsy-turvy one in which men were known as women, friends as sisters, and lovers as wives and husbands.

Camp's inclusion within this secret lingua franca is evident in a letter from the notorious British female impersonator Frederick "Fanny" Park dating to 1868: "My 'campish' undertakings are not at present meeting with the success which they deserve. Whatever I do seems to get me into hot water somewhere. But n'importe. What's the odds so long as you're happy?" The letter was addressed to the lover of Fanny's friend and fellow cross-dresser, Ernest "Stella" Boulton.

When Fanny and Stella were later tried for conspiracy to seduce men by wearing women's clothing, the prosecutor read Fanny's letter aloud, misreading "campish" as "cawfish." From the confusion that followed, it was obvious that neither judge nor jury understood the word's meaning, attesting to its "secret status." Despite an impressive number of witnesses for the prosecution and a dazzling array of clothing from Fanny and Stella's "drag wardrobe" presented for the jury's consideration, they were acquitted of all charges. Following their cause célèbre, they became "camp" heroines of queer culture.

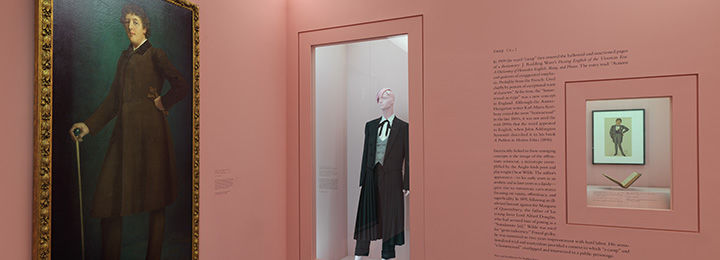

In 1909 the word "camp" first entered the hallowed and sanctioned pages of a dictionary: J. Redding Ware's Passing English of the Victorian Era: A Dictionary of Heterodox English, Slang, and Phrase. The entry read: "Actions and gestures of exaggerated emphasis. Probably from the French. Used chiefly by persons of exceptional want of character." At the time, the "homosexual-as-type" was a new concept in England. Although the Austro-Hungarian writer Karl-Maria Kertbeny coined the term "homosexual" in the late 1860s, it was not until the mid-1890s that the word appeared in English, when John Addington Symonds described it in his book A Problem in Modern Ethics (1896).

Inextricably linked to these emerging concepts is the image of the effeminate aristocrat, a stereotype exemplified by the Anglo-Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde. The author's appearance—in his early years as an aesthete and in later years as a dandy—gave rise to numerous caricatures focusing on vanity, effeminacy, and superficiality. In 1895, following an ill-advised lawsuit against the Marquess of Queensbury, the father of his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas, who had accused him of posing as a "Somdomite [sic]," Wilde was tried for "gross indecency." Found guilty, he was sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labor. His sensationalized trial and martyrdom provided a context in which "a camp" and "a homosexual" overlapped and intersected in a public personage.

In his 1954 novel The World in the Evening, Christopher Isherwood presents camp as a dichotomy: high camp versus low camp. For Isherwood, high camp is the "whole emotional basis" of the ballet and of Baroque art, a sophisticated, connoisseur-like mode that prompts discussions of "aesthetics or philosophy or almost anything." Isherwood regards it as more fundamental than low camp, which he considers "an utterly debased form" that in "queer circles" connotes "a swishy little boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich."

Paul Cadmus's 1934 painting The Fleet's In!, on view here, can be read as a distillation of Isherwood's dichotomous interpretation of camp. On the one hand, its subject matter epitomizes the author's definition of low camp, most notably the figure at left who solicits a sailor by offering him a cigarette. The man's "gay status" is asserted by his tight-fitting suit and red tie, which, along with his bleached blond hair, were coded signifiers of homosexuality in the first half of the twentieth century. On the other hand, the painting's dynamic composition, which owes a clear debt to the Italian Renaissance (especially the paintings of Luca Signorelli and Andrea Mantegna) epitomizes Isherwood's definition of high camp. As he asserted, "True High Camp always has an underlying seriousness. . . . You're expressing what's basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance."

By the time Susan Sontag published "Notes on 'Camp'" in the Fall 1964 issue of Partisan Review, the word "camp" had begun to appear in various literary and popular magazines. However, Sontag was the first writer to explore camp as a serious subject, one worthy of critical and cultural analysis. She approached it as an esoteric, fugitive "sensibility" that she catalogued in the form of fifty-eight notes.

Locating the origins of camp in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries "because of that period's extraordinary feeling for artifice, for surface, for symmetry," Sontag framed it as an "unmistakably modern" sensibility that reflected the revolutionary impact of the 1960s and the challenge brought to the intellectual establishment by popular culture. In her efforts to capture the "sensibility of an era," she presented camp as an aesthetic that promoted "the equivalence of all objects." Through an indifference toward distinctions between high art and popular culture as well as between original and replica, camp effected a democratic leveling of artistic and cultural hierarchies.

Many of the objects and artists mentioned in "Notes on 'Camp'" are represented in The Met collection, with which Sontag was intimately familiar (she visited the Museum frequently). The more than forty examples brought together in this gallery effectively illustrate the author's camp landscape of "wild(e) indifference."

In "Notes on 'Camp,'" Susan Sontag presents an opposition between naïve camp and deliberate camp that in many ways parallels Christopher Isherwood's dichotomy of high camp and low camp. She considers naïve camp to be unconscious and unintentional, and deliberate camp to be calculated and manufactured: "Camp which knows itself to be Camp . . . is usually less satisfying." For Sontag, the essential element of naïve camp is "a seriousness that fails," but "not all seriousness that fails can be redeemed as Camp. Only that which has the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve."

Sontag's distinction, which holds true today, can be applied to the fashions in this gallery. Displayed here are examples of naive camp by designers such as Salvatore Ferragamo, Paul Poiret, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Antonio del Castillo, and Yves Saint Laurent, set alongside examples of deliberate camp by Alessandro Michele, Mary Katrantzou, Jeremy Scott, Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren, and Thierry Mugler.

Despite this distinction, however, what these fashions share is a certain stylized aestheticism, an essential "love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration"—Sontag's defining elements of the camp sensibility.

In her essay, Susan Sontag observed that "Camp taste has an affinity for certain arts rather than others," citing fashion as one of those arts. Yet Sontag offers only two examples: "women's clothes of the twenties" and "a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers." More critical to appreciating fashion as a key expression of the camp sensibility is Sontag's analysis of its formal characteristics: irony, humor, parody, pastiche, naïveté, duplicity, ambiguity, artificiality, theatricality, extravagance, exaggeration, and aestheticism. All of these characteristics—either singly or jointly—are apparent in the fashions shown here.

While the first section of the exhibition functions as a series of "whispering" galleries, as befits camp's clandestine status before its "outing," the second presents an "echo chamber." Although Sontag's voice can be heard the loudest, she is joined by other voices of camp criticism that came afterward, including those of Mark Booth, Fabio Cleto, Philip Core, and Karl Keller—their assertions bouncing off one another as well as off the fashions.

The designs are organized under eighteen statements that communicate key aspects of the camp sensibility. Within these groupings, each ensemble is accompanied by a comment that speaks to the complicated and multifaceted nature of camp. While experienced as a cacophony, these remarks, which are spoken aloud by designers in the exhibition, together point to the essential spirit of the camp sensibility: its all-inclusive, all-embracing magnanimity.

Ensemble by Bertrand Guyon (French, born 1965) and headpiece by Stephen Jones (British, born 1957) for House of Schiaparelli (French, founded 1927), fall/winter 2018–19 haute couture. Courtesy of Schiaparelli. Photo © Johnny Dufort, 2019