What’s the earliest known portrait? Some say it’s a sculpted piece of mammoth ivory from the last ice age, a 27,000-year-old cave painting in Vilhonneur, France, or a prehistoric rock painting in modern-day Australia. While it’s impossible to know, one thing is clear: soon after people began making images, we began making images of other people.

Today, if you search for “portrait” on The Met’s online collection you’ll find over forty-five thousand artworks spanning millennia and encompassing a wide range of subjects. From aristocrats to deities, self-portraits to everyday people, these artworks represent a timeless drive to record—in some cases, to immortalize—what it means to be human.

Here, fourteen staff members across the Museum share individual portraits that reveal surprising and intimate aspects of our shared humanity.

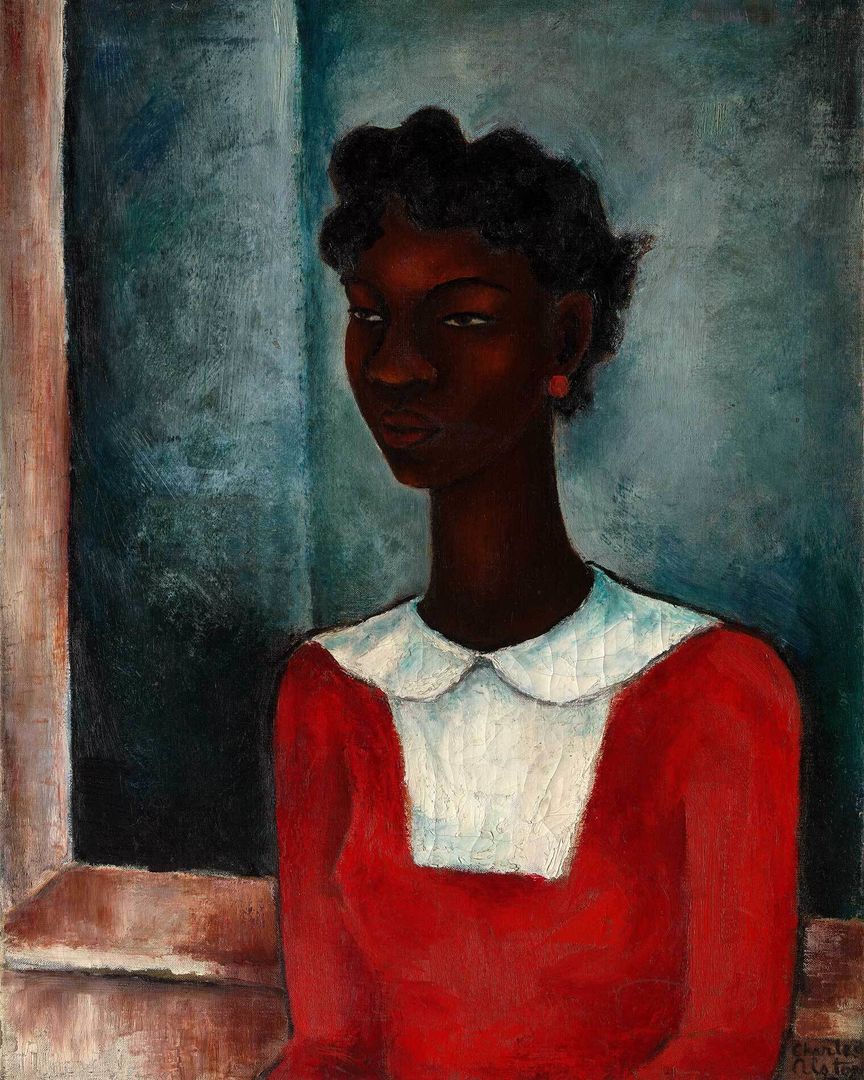

Charles Alston’s Girl in a Red Dress

Charles Alston (American, 1907–1977). Girl in a Red Dress, 1934. Oil on canvas, 28 × 22 in. (71.1 × 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift and George A. Hearn Fund, 2021 (2021.25). © Estate of Charles Henry Alston. On view in Gallery 902.

Charles Alston’s Girl in a Red Dress (1934) exemplifies the portrait as an icon—as a portrayal of the artist’s ideals more than a specific individual. While Alston painted this young woman from life, his title does not record her identity. He depicts her as emblematic of core Harlem Renaissance aesthetic values. With her gracefully elongated neck and sculpted face, she embodies the artist’s signature blend of expressionism and modernism with the stylization of African sculpture. Her enigmatic gaze to the side underscores Alain Locke’s 1925 exhortation that the “New Negro” artist “must invest the modern black … not only with beauty and urban sophistication but with … psychological depth.” Alston kept this painting in his studio until his death.

— Denise Murrell, Associate Curator, 19th and 20th Century Art

Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano) (Italian, 1503–1572). Portrait of a Young Man, 1530s. Oil on wood, 37 ¾ × 29 ½ in. (95.6 × 74.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.16). On view in Gallery 999 as part of the exhibition The Medici: Portraits and Politics, 1512–1570.

Bronzino parodies the mask-like face of his young, aloof Florentine sitter with grotesque heads on the furniture and a face that is formed, as though by chance, by the fabrics to the right of his codpiece. These grotesque heads express the kinds of ironic reversals and ambiguity found in Bronzino’s satiric poetry and reflect the ultra-sophisticated world to which this sitter aspired. He holds a small volume of poems by Petrarch. Both Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Edgar Degas took inspiration from portraits such as this, marking the extended influence of Bronzino’s sixteenth-century work.

— Keith Christiansen, Curator Emeritus, Department of European Paintings

Walker Evans’s portrait of a woman in Havana

Walker Evans (American, 1903–1975). [Woman Behind Barred Window, Havana], 1933. Film negative, 6 ½ × 8 ½ in. (16.5 × 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive, 1994 (1994.256.260). © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not on view.

Among the thousands of images comprising The Met’s Walker Evans Archive, “Woman Behind Barred Window, Havana” (1933)—a photograph Walker took during a trip to Cuba—stands out to me. Captured in 1933, twenty years before the Cuban Revolution, an event that would lead to a mass exodus of native Cubans from the island, this portrait feels almost prophetic to a Cuban American viewer such as myself. For an island that would soon restrict migration and imports, and impose strict censorship laws, the barred window that separates and obscures the subject from the viewer transforms the image into a visual metaphor for the country and its citizens, both on and off the island. Of course, Evans couldn’t have known anything about these future events. Nevertheless, the beauty of portraiture lies in the connections and associations it can inspire within the viewer.

— Victoria Martinez, Social Media Producer, External Affairs

Moche ceramic portrait vessels

Left: Portrait head bottle, 3rd–6th century. Peru, Moche. Ceramic, pigment, slip, 10 ½ × 6 ½ × 7 in. (26.4 × 16.2 × 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1882 (82.1.28). Right: Fox head bottle, 5th–7th century. Peru, Moche. Ceramic, slip, 12 ½ × 6 ½ × 8 in. (31.8 × 16.5 × 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Nathan Cummings, 1963 (63.226.6). Not on view.

Portraiture was not common in the Americas prior to the sixteenth century, but during certain periods and places the genre was explored in creative and intriguing ways. In the middle of the first millennium A.D., on Peru’s north coast, potters produced great numbers of ceramic bottles in the shape of heads. Often called “portrait vessels,” some seem to depict specific individuals at different stages of their lives, from youth through maturity. both as youths and older adults. The close attention to physiognomic detail temptingly hints at living, breathing historical personages—a rare chance to imagine members of a community without written histories. Yet are such images straightforward portraits of heroic leaders or victorious warriors? What does it mean when a fox is given the same treatment?

— Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator, & Hugo C. Ikehara-Tsukayama, Andrew A. Mellon Curatorial Fellow, Ancient American Art in The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Leonora Carrington’s Self-Portrait

Leonora Carrington (Mexican [born England], 1917–2011). Self-Portrait, ca. 1937–38. Oil on canvas, 25 ½ × 32 in. (65 × 81.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection, 2002 (2002.456.1). Image © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Not currently on view; included in the exhibition Surrealism Beyond Borders.

Leonora Carrington’s Self-Portrait draws on her interests in alchemy, the tarot, and Celtic folklore. Painted in Paris following her introduction to Surrealism at the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, the canvas reflects Carrington’s response to gender stereotypes. The artist sits in a room beside a lactating hyena, while a white horse—associated with the Celtic goddess of fertility and a symbol of Carrington herself—runs free. The scene has the look of a dream, but with a clear message about freedom. Looking back, the artist commented about her role in Surrealism, “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse.”

— Stephanie D’Alessandro, Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern Art and Curator In Charge of the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art

A mask representing Jikokuten, one of the Four Kings of Heaven

Inscribed by Myōchin Muneakira (Japanese, 1673–1745). Mask, 1745. Iron, lacquer, te×tile (silk), 9 ½ × 7 × 9 in. (24 × 18.1 × 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1919 (19.115.2). Not on view.

With the peace and prosperity of the Edo period (1615–1868), war masks, which had been in use in Japan since the fifteenth century, became a form of artistic and individualistic expression. This war mask, made from a single sheet of iron by Myōchin Muneakira in 1745, is not only the most important Japanese mask in The Met collection, but was already famous among Samurai circles by the time a drawing of it was first published in 1763. Intended to invoke divine protection for its wearer, the mask represents Jikokuten, one of the Four Kings of Heaven, and incorporates specific features of the deity—such as his diadem, prominent eyebrows, and large ear lobes—as seen in Buddhist portraits.

— Markus Sesko, Visiting Researcher, Department of Arms and Armor

A pair of pistols made for a king and queen

Pair of flintlock pistols made for Ferdinand IV, King of Naples and Sicily (1751–1825), ca. 1768. Italian, Naples. Manufacturer: Royal Arms Manufactory at Torre Annunziata (Italian, Naples, established 1757); Gunsmith: Michele Battista (Spanish, active in Naples, Italy, recorded about 1760–90); Barrelsmith: Emanuel Esteva (Spanish, active in Naples, Italy, recorded about 1768–73). Steel, gold, wood (walnut), silver, L. of each 17 ⅜ in. (44.1 cm); L. of each barrel 11 in. (28.1 cm); Cal. .63 in. (16.0 mm); Wt. of each 2 lb. 4 oz. (1021 g). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Henry Walters, 1926 (26.259.5, .6). On view in Gallery 375.

Among the European firearms in the Museum’s collection that incorporate portraiture as a prominent and informative component of their decorations, this pair of Neapolitan pistols stands out for its grandeur and probable association with a specific event. Here, a medallion portrait of a young man and woman adorns the pommel of each pistol, respectively, rendered in highly polished chiseled steel against a matte gold background. The matching portraits are believed to represent King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Sicily (1751–1825) and his new wife Queen Karoline (1752 –1814), and they offer compelling evidence that the pair was made to commemorate their marriage in 1768.

— John Byck, Associate Curator, Department of Arms and Armor

A portrait of a prince holding a falcon

Prince Holding a Falcon, ca. 1820. Oil on canvas, 75 ¼ × 29 ½ in. (191 × 74.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 2017 NoRuz at The Met Benefit, 2017 (2017.646). On view in Gallery 462.

Arch-shaped oil paintings like this charming portrait of a prince holding a falcon were not meant to be displayed alone. They were inserted into niches in palaces and pavilions, part of a larger decorative ensemble for architectural interiors. Typical of life-size portraits produced in early nineteenth-century Iran, the painting is an idealized depiction of a prince. It accentuates his lavish jewel-studded costume and accoutrements, astrakhan hat, and aigrette. Touching his saber sheath with one hand, he holds a falcon with the other. Falconry, a privileged sport of royalty and nobility in Iran for centuries, was enjoyed by Qajar princes.

— Maryam Ekhtiar, Patti Cadby Birch Curator, Department of Islamic Art

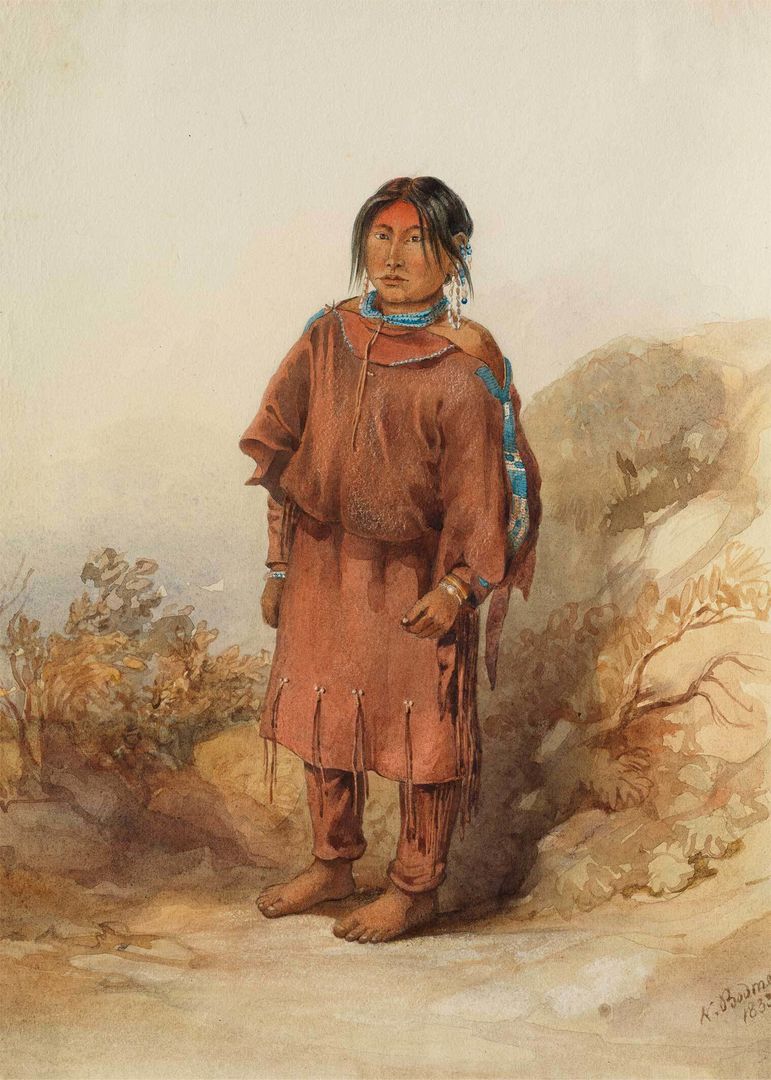

Karl Bodmer’s Assiniboine and Siksika Blackfoot Girl

Karl Bodmer (Swiss, 1809–1893). Assiniboine and Siksika Blackfoot Girl, 1833. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 10 ½ × 8 in. (27 × 20.3 cm). Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Gift of the Enron Art Foundation (1986.49.378). Photograph courtesy Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska © Bruce M. White, 2019. On view in Gallery 746 as part of the exhibition Karl Bodmer: North American Portraits.

Like many of the portraits Bodmer created during his 1833–34 voyage on the upper Missouri River, Assiniboine and Siksika Blackfoot Girl both obscures and yields information about the artist, the sitter, and Native lifeways. Due to cultural protocols, Bodmer, a European man, wouldn’t have spent much time with Indigenous women and children, and when he did, he seldom recorded their identities. Why he finished this particular likeness with special care is unknown; he signed and dated it and added a landscape setting—features unusual to his portraits. Strands of glass beads ornamenting the girl’s ears, neck, and arms as well as panels of trade beads on her hide dress attest to dynamic, far-flung exchange routes and Indigenous beadwork practices.

— Thayer Tolles, Marica F. Vilcek Curator, The American Wing

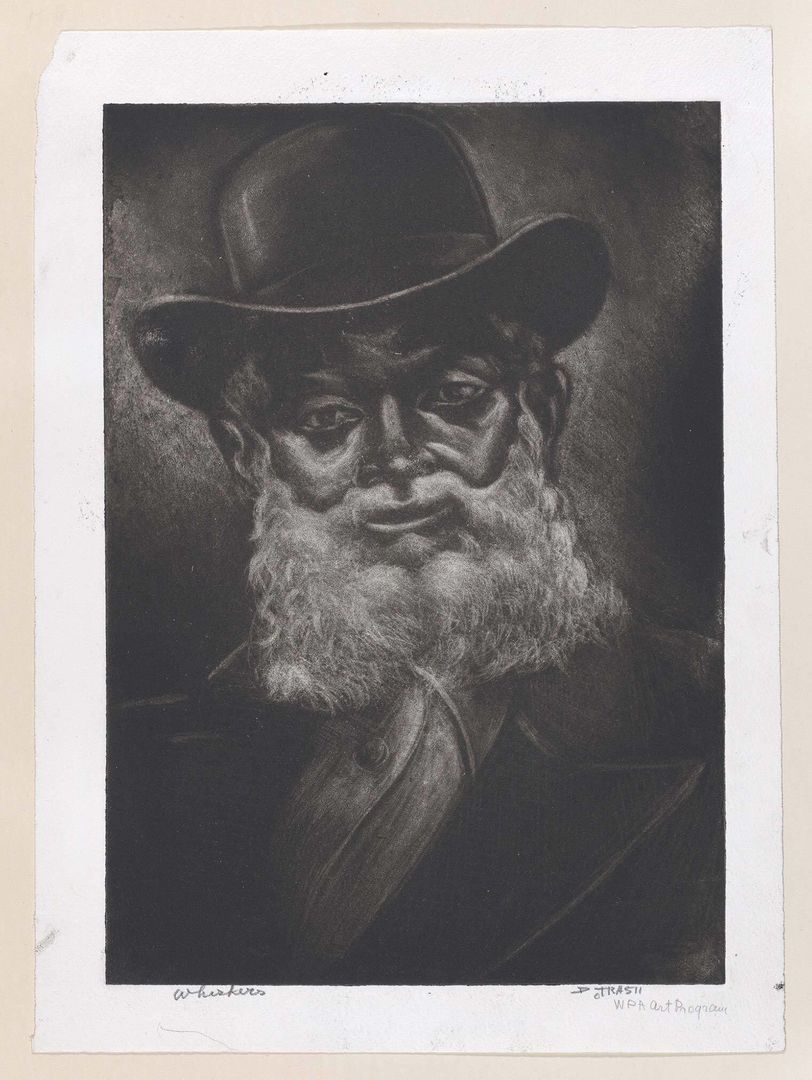

Dox Thrash’s Whiskers

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Whiskers, ca. 1939–40. Carborundum mezzotint, sheet: 11 ½ × 8 ⅜ in. (29 × 21.2 cm) plate: 9 ¾ × 6 ⅞ in. (25 × 17.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Work Projects Administration, Pennsylvania, 1943 (43.46.78). Not on view.

Whiskers exudes a warm glow that befits the affable expression of its subject, an unidentified man who dons a bowler hat and full beard. It is one of dozens of portraits of Black sitters that Dox Thrash created using carborundum mezzotint, a technique he developed while working at the Philadelphia-based workshop of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. The project was established by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal government to provide funding to unemployed artists during the Great Depression. Thrash, a seasoned printmaker when he joined the workshop, adapted the mezzotint process, invented in the seventeenth century, by using carborundum powder to abrade the metal plate. Working from dark to light, he burnished, or smoothed, the rough surface to form his composition, achieving a wide tonal range of rich blacks.

— Allison Rudnick, Associate Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints

Asmat shields depicting the bearer’s ancestors

Left: Pono. Shield, mid-20th century. Indonesia, Papua Province (Irian Jaya), Momogo or Agani village (?), Pomatsj River (northern tributary). Asmat people. Wood, paint, sago palm leaves, 58 1/4 x W. 17 1/4 in. (148 x 43.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection; Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller and Mrs. Mary C. Rockefeller, 1965 (1978.412.919). Right: Shield, mid-20th century. Indonesia, Papua Province (Irian Jaya), Erma, Pomatsj River. Asmat people. Wood, paint, sago palm leaves, 62 1/2 x 17 x 7 in. (158.8 x 43.2 x 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection; Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller and Mrs. Mary C. Rockefeller, 1965 (1978.412.898). Not on view.

In Western New Guinea, the most important depictions of Asmat ancestors are integrated into men’s shields. Many have great character, with lively and easily identifiable features including faces, arms, and legs. Portraits of specific ancestors appear as schematic designs carved in low relief into the shield’s surface or as abstract motifs highlighted and animated with natural pigments. One of these is lime (crushed shell or coral), which is a direct reference to Safan, the spiritual realm where the ancestors and spirits reside. The portraits’ agency is paramount. Enlivened with incantations prior to a headhunting raid, the ancestors’ presence enhanced the shield’s spiritual armature, reinforcing the bearer’s strength and power, and guiding him toward heightened success in the battle or raiding party.

— Maia Nuku, Evelyn A. J. Hall & John A. Friede Curator, Oceanic Art in The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

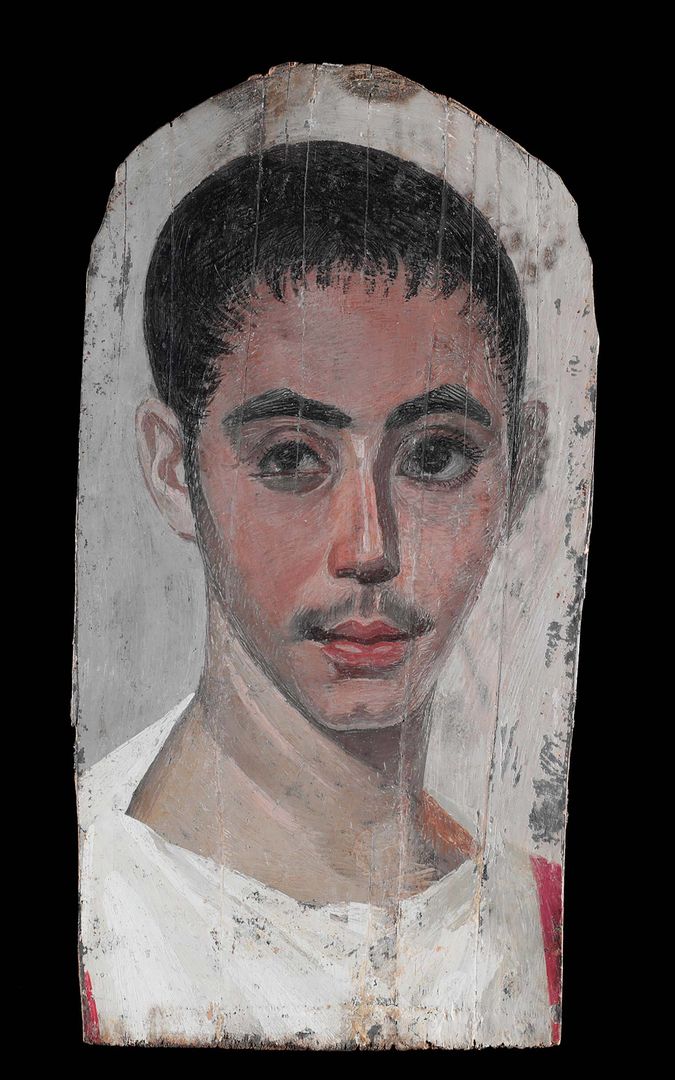

Egyptian funerary portraits

Portrait of a Youth with a Surgical Cut in One Eye, A.D. 190–210. Egypt, Roman Period. Encaustic paint on limewood, 13 ¾ × 6 ¾ in. (35 × 17.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1909 (09.181.4). On view in Gallery 138.

Ancient Egyptian artists generally depicted individuals with idealizing features stressing confidence, vitality, and youthfulness, albeit with some notable exceptions. In the mid-first to mid-third centuries A.D., Roman portrait traditions entered Egypt in the form of panel paintings that covered the faces of wrapped mummies. These works, depicting members of a multiethnic society, stress individuality and even show signs of illnesses. The young man depicted on this panel is notable for his smaller right eye with a healed surgical incision across the lower lid, likely indications of a congenital condition. Lively brushwork emphasizes the jawline, contours of the cheeks, wispy hair of the mustache, and thick, arching brows.

— Adela Oppenheim, Curator, Department of Egyptian Art

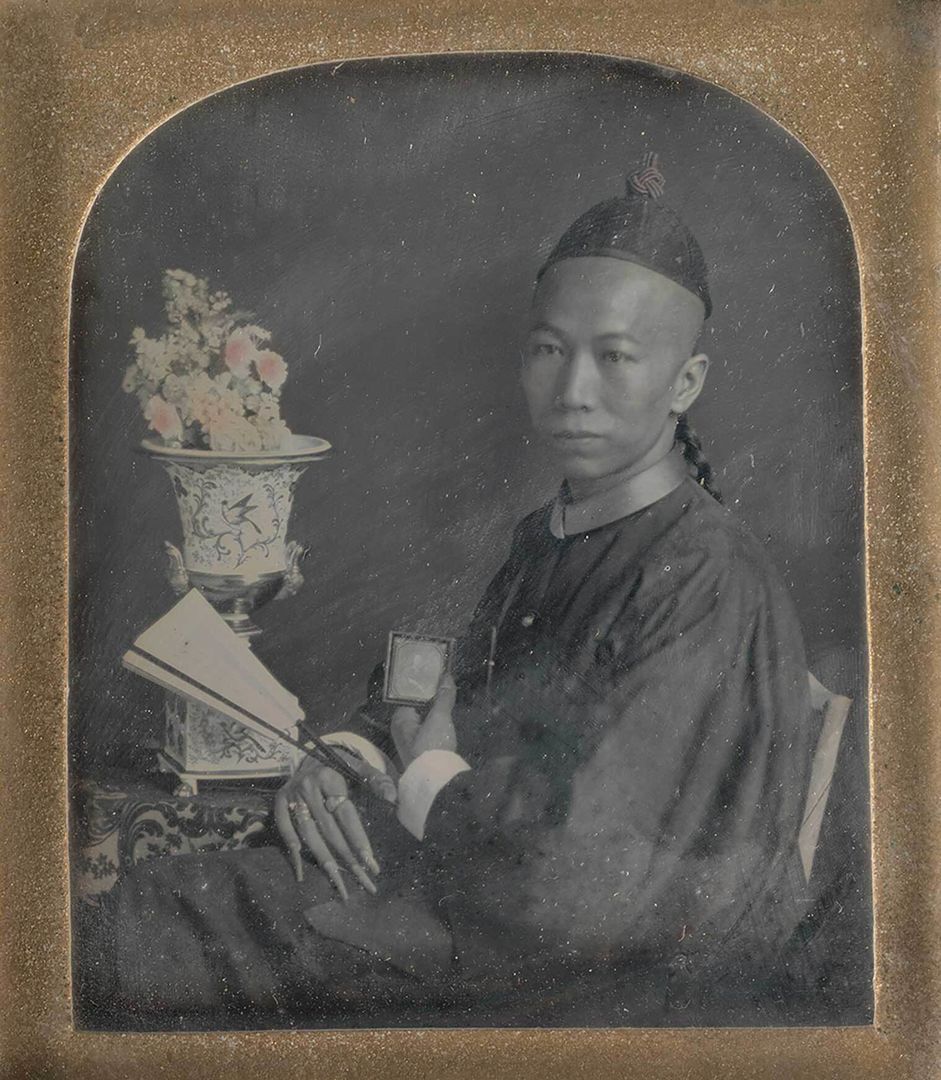

Portrait of T’sow-Chaoong by an unknown photographer

Unknown photographer (American). [Portrait of T’sow-Chaoong], 1845–47. Daguerreotype, 2 ¾ × 2 ¼ in. (7 × 5.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005 (2005.100.360). Not on view.

A young man, whose rosy cheeks echo the delicate cut flowers in the vase beside him, carefully cradles a daguerreotype in one hand and a fan in the other. These attributes, in addition to his ringed fingers and long nails, signal his status as a gentleman and scholar. Indeed, T’sow-Chaoong was a “Writing Master” and one of two Cantonese cultural ambassadors engaged at Boston’s Chinese Museum (1845–47) to promote understanding between the United States and China on the heels of a trade agreement between the two countries. At the museum, he demonstrated calligraphy by writing the names of visitors, including the poet Emily Dickinson, on calling cards that doubled as souvenirs.

— Stephen C. Pinson, Curator, Department of Photographs