The Nile Valley is first inhabited in the Lower Paleolithic Period (ca. 300,000 B.C.–90,000 B.C.). Neolithic people continue to create stone tools, and exploit domesticated plants and animals (7000–4500 B.C.). In the ensuing millennia many forms of art flourish, including jewelry (faience beads), ceramic vessels, geometric figures, and pottery, much of which is found in tombs. Hierakonpolis in the south, the largest Predynastic settlement known, is the center of political control. The pyramids of Giza and Saqqara arise in the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.), one of the most dynamic and innovative periods in Egyptian culture. Power decentralizes during the First Intermediate Period (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.), only to be unified again by the Theban king Mentuhotep II in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.).

Egypt, 8000–2000 B.C.

Timeline

8000 B.C.

6500 B.C.

ANCIENT EGYPT

ANCIENT NUBIA (SEE ALSO SUDAN)

6500 B.C.

5000 B.C.

5000 B.C.

3500 B.C.

ANCIENT EGYPT

ANCIENT NUBIA (SEE ALSO SUDAN)

3500 B.C.

2000 B.C.

ANCIENT EGYPT

ANCIENT NUBIA (SEE ALSO SUDAN)

Overview

Key Events

-

ca. 300,000–7000 B.C.

(Paleolithic) Archaeologists have designated this long stretch of time the Paleolithic period because most tools are made from stone. Based on finds, we know that people inhabited both the Nile valley and its nearby deserts as environmental conditions permitted. The Lower Paleolithic period (ca. 300,000–90,000 B.C.) is the earliest occupation known in Egypt and these ancestors of humans often used a bifacial tool we call the Acheulian hand ax. It is easily recognized and examples have been recovered in many parts of the desert. From about 90,000 to 35,000 B.C., groups of Middle Paleolithic people who settled at springs in the desert and along the river left behind more sophisticated tool kits that are dominated by blades and retouched bifaces. Upper Paleolithic cultures (ca. 35,000–7000 B.C.) produced tool kits composed largely of monoliths. Sites from this latter period have also yielded hearths, plant and animal remains, and a few human burials.

-

ca. 7000–4500 B.C.

(Neolithic) The earliest permanent settlements belong to this period. Their occupation is identified from the remains of huts, hearths, granaries, and nonportable stone tools for grinding grains. People had now begun to exploit domesticated plants and animals, although animal bones indicate that hunting of birds, small game, and fish continues to be important to the economy. Stone tools remain significant components of the material culture, but tools of bone and ceramic vessels are now used as well. At the site of Merimde Beni Salama in the Delta, a representation of a human face is the earliest known example of sculpture from ancient Egypt.

-

ca. 4500–3800 B.C.

(Badarian Period) Although most sites of this period are cemeteries located in the low desert of the Nile valley proper, the Delta site of Merimde Beni Salama is the largest known in Egypt from this time. The Nile valley sites located in Middle Egypt in the vicinity of the modern town of Badari give the period its name. The numerous Badarian cemeteries reveal a formal burial program that includes constructing a tomb, positioning the body, and supplying the deceased with equipment for an afterlife. The most common burial objects are finely made bowls of Nile clay in brown or red. Tombs occasionally contain jewelry—including the earliest glazed stone beads—and sometimes small human figures of ivory.

-

ca. 3800–3650 B.C.

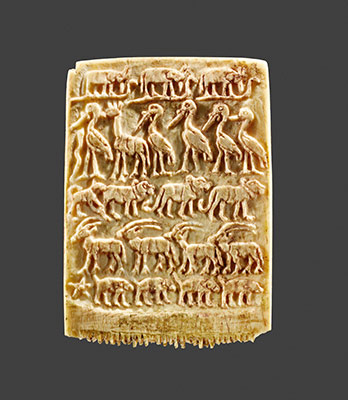

(Naqada I) Occupation increases throughout the Nile valley and cemeteries and settlements appear in a number of places in the Delta as well. None of the known sites is very large, although Hierakonpolis far to the south is the largest population center known. Settlement size and distribution are primarily understood from the well-known cemeteries of the period, including those near the modern town of Naqada in Upper Egypt, for which the period is named. The formal burial program begun in the Badarian Period continues, with increased numbers of ceramic vessels—some of which display geometric figures and hunting scenes—placed in the tombs along with stone vessels and slate cosmetic palettes of rhomboid and animal forms. As in the Badarian Period, figures and jewelry are occasionally placed in tombs, especially at the end of the period and into early Naqada II. Village economies are based on agriculture and herding, although wild birds and fish supplement the diet.

-

ca. 3650–3300 B.C.

(Naqada II) Substantial change in the social organization of Predynastic society occurs during this period, identified by the size and arrangement of settlement and cemetery sites as well as the contents of tombs. Burial goods are similar to those of the Naqada I Period, although styles of vessels and palettes change. Faience, a glazed ceramic material, appears for the first time, largely in the form of beads. Some members of Naqada II society seem to have access to greater wealth, allowing them to construct more elaborate tombs with richer contents. Items signifying high status in later periods begin to appear, again indicating social differentiation among the population. A new type of pottery is made from a buff-colored desert clay and decorated in red paint with geometric forms and boat and desert scenes. The clay is rare and the decorative forms consistent. Consequently, it is believed that, unlike other ceramic types, this pottery was produced in only a few workshops rather than by each village.

-

ca. 3300–3100 B.C.

(Naqada III) The most important cultural changes associated with this period are reflected in representations on objects. The scenes on large, ceremonial slate palettes indicate that one individual holds significant power. This individual is depicted with numerous symbols linked to Egyptian kingship in pharaonic times. The scenes are carved in some of the earliest known raised relief, and palettes as well as small ivory labels or tags display the first stages of hieroglyphic writing. Symbols of various pharaonic deities occur on palettes, tags, and a few three-dimensional objects. Hierakonpolis is the largest Predynastic settlement and may be the center of political control, but the sites of Naqada and Abydos are significant as well. It is now known that Abydos was the burial ground of late Predynastic leaders, testifying to the importance of this region.

-

ca. 2649–2150 B.C.

(Old Kingdom, Dynasties 3–6) The Old Kingdom, best known for the pyramids of Giza and Saqqara, is one of the most dynamic and innovative periods for Egyptian culture. Not only do the Egyptians master the art of building in stone, but over a period of 500 years they define the essence of their art, establishing artistic canons that will last for more than 3,000 years.

-

ca. 2150–2030 B.C.

(First Intermediate Period, Dynasty 8–mid-Dynasty 11) By the end of the Old Kingdom, centralized power has weakened. During the First Intermediate Period, Egypt is ruled by two competing dynasties, one based at Heracleopolis in the north, the other based at Thebes in the south.

-

ca. 2030–1640 B.C.

(Middle Kingdom, mid-Dynasty 11–Dynasty 13) The Theban king Mentuhotep II reunites Upper and Lower Egypt, establishing the capital at Thebes and ushering in the Middle Kingdom. A renewed flowering of the arts is evident, especially in Mentuhotep’s innovative funerary temple in western Thebes, and in the exquisite painted reliefs decorating this structure and the tombs of officials in the surrounding cemeteries. For more information, see Middle Kingdom.

Citation

“Egypt, 8000–2000 B.C.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=02®ion=afe (October 2000)

Related

Map

Primary Chronology

Secondary Chronology

Lists of Rulers

Keywords

- Africa

- Ancient Egyptian Art

- Cairo

- Early Dynastic Period in Egypt

- Egypt

- Egyptian Art in the Middle Kingdom

- Egyptian Art in the Old Kingdom

- First Intermediate Period of Egypt

- North Africa

- Predynastic Period in Egypt

- Prehistoric Art

- 8th Millennium B.C.

- 7th Millennium B.C.

- 6th Millennium B.C.

- 5th Millennium B.C.

- 4th Millennium B.C.

- 3rd Millennium B.C.