After the turn of the millennium, political conflicts in Great Britain and Ireland center on the Scandinavian presence and links to Normandy. Although regional leaders of the early Middle Ages are ultimately subsumed into more centralized governments, the area still faces the threat of invasion. In 1066, at the Battle of Hastings, the Normans successfully defeat the English, becoming the new rulers of the English mainland. The marriages of several English rulers to the great Norman families create strong, long-term connections between the two cultures, but also result in repeated conflict. In Scotland, the long process of tribal integration culminates in the reign of Alexander III, who conquers the islands of the Hebrides. Wales, the other British stronghold of Celtic art and society, is organized during this period into three kingdoms—Gwynedd, Powys, and Deheubarth, each ruled by their own princely family. Ireland is also fragmented, with a titular High King not in reality acknowledged by all the smaller kings under him, and without the strength to force obedience on them.

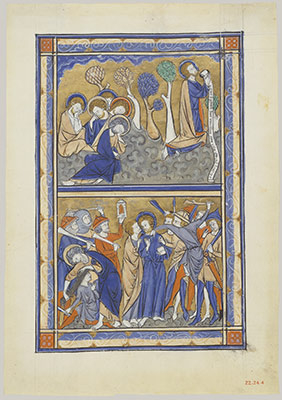

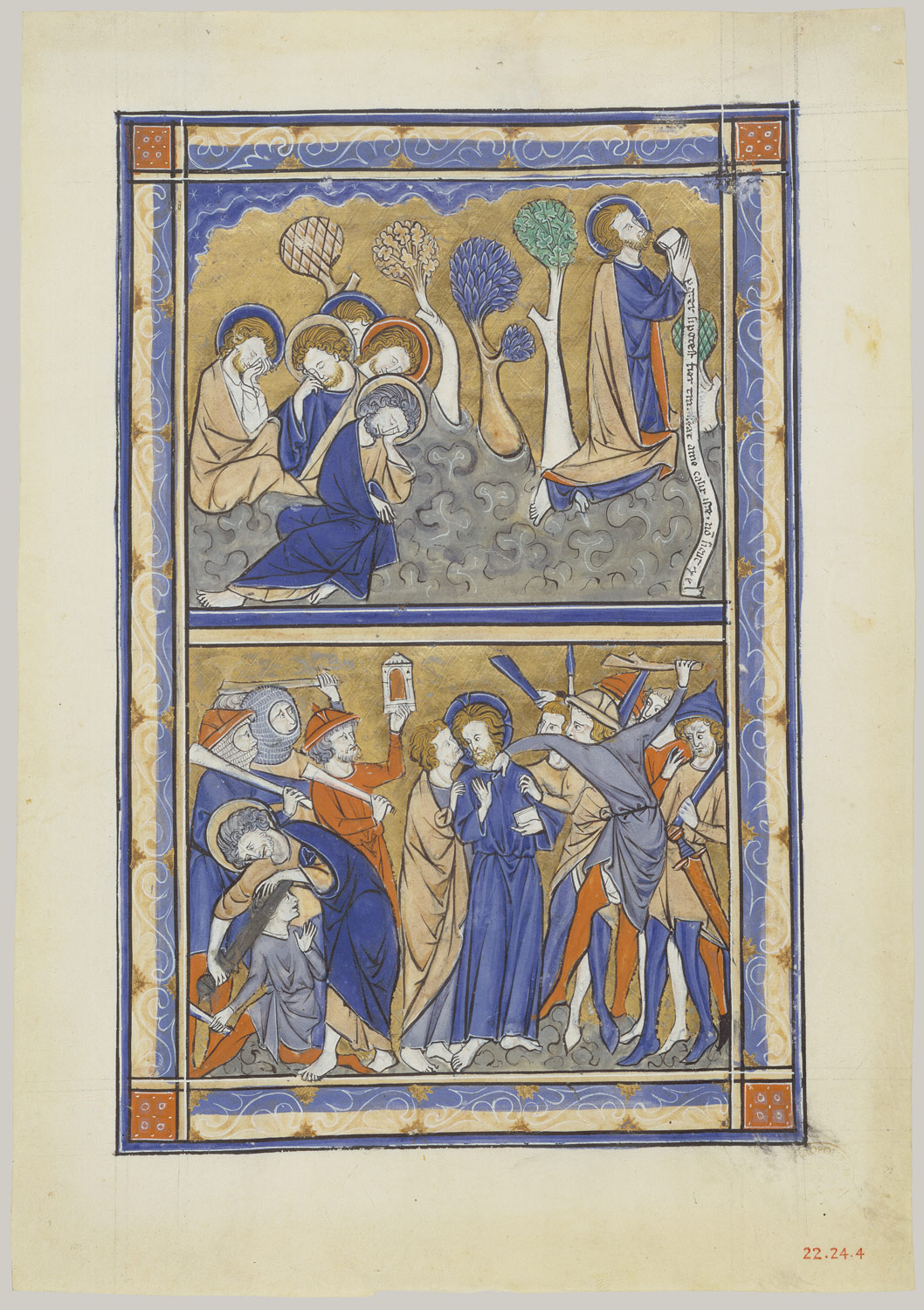

With the arrival of the Normans, art and architecture produced in England reflects French influence. The Norman and Plantagenet kings hold French territory during the period, and artists and objects travel between the two countries. Majestic cathedrals are erected from the end of the eleventh century; those at Durham, Canterbury, Ely, Wells, and Lincoln are among the most famous. By the end of the period, English embroideries are so renowned for their refinement that they are known throughout Europe as opus anglicanun.