Virgin and child

Initially ascribed to Jacopo Sansovino, this bronze group joined the corpus of works assigned to that ingratiating artist Nicolò Roccatagliata thanks to Hans Weihrauch and Bertrand Jestaz. Weihrauch recognized the correspondence between our statuette and an autograph standing bronze Virgin and Child (fig. 66a)—then in the Musée de Cluny, Paris—and attributed both to Roccatagliata. Jestaz verified the signature, NICOLLINI F., on the bronze in France as that of our artist.[1]

Weihrauch further speculated that The Met Virgin and Child, which he considered one of Roccatagliata’s mature creations, was the same work described in 1674 by the sculptor’s biographer Raffaele Soprani as “a small figure of bronze representing the sitting Virgin with the infant Jesus on her lap . . . made by the artist with correct and harmonious proportions. And after having been dutifully cleaned by his son Simone, it was placed in a niche of marble over a door of a house in that street [in Genoa] that leads from the new Piazza delle Erbe directly to the city gate of Sant’Andrea.”[2] Soprani’s book was republished in 1768 by Carlo Ratti, who noted that the Virgin and Child had by then disappeared.[3]

It is indeed likely that The Met Virgin and Child is the same bronze to which Soprani referred. Since he reported that Roccatagliata’s work was placed above a door, such a position would necessitate a sculpture of a certain size and of a composition suited to be seen from below. Both requirements are met by our group: it is considerably bigger than a bronze destined for the private enjoyment of a collector, and both figures gaze downward. The fact that it is not modeled fully in the round but has an open back further indicates that it was intended for installation against a wall. That this must have been an exterior wall is suggested by the condition of our statuette, which seems to be the result of several layers of protective coating, typical of bronzes that have been displayed outdoors. One may thus assume that The Met’s Virgin and Child once graced the facade of a house in Genoa, which was, according to Soprani, situated in the historic city center, on today’s Salita del Prione, a winding street connecting Piazza delle Erbe and Porta Sant’Andrea, also called Porta Soprana. The Madonna was placed above the entrance door in a niche or aedicula. Such votive shrines were once very popular and could be found on practically every other corner of any European city. Very often they were devoted to the Virgin, which was particularly the case in Genoa, because the Genoese doge Ottavio Fregoso (r. 1513–15) had commanded that the insignia of foreign rule be removed from all houses and replaced with images of the Madonna, who in 1637 was solemnly ordained the official queen of the city.[4] The original setting of our Virgin and Child can thus be reconstructed fairly accurately, but we do not know when and why it was removed from the house in Genoa.

Since Weihrauch’s attribution of the Virgin and Child to Roccatagliata in 1967, knowledge about the artist has grown considerably.[5] Nicolò was born in Genoa, where he entered the workshop of the goldsmith Agostino Groppo at the age of ten or eleven. Later he moved to Venice and, together with Agostino’s son Cesare, operated a successful workshop that specialized in decorative bronzes for churches such as statuettes of saints, elaborate candelabra, and narrative reliefs. Cesare Groppo died in 1606. By 1615, Roccatagliata’s son—who was called Sebastiano and not Simone, as stated by Soprani—was effectively running the business, faithfully continuing the shop style, while Nicolò disappears from the documents, although he lived until 1629. According to Soprani, he had become blind in one eye and returned to Genoa with a friend, the wood and ivory carver Domenico Bissone. The return was not permanent, however. Roccatagliata died in Venice, where his name continued to be of good repute, as can be deduced from the fact that the so-called paliotto of San Moisè (p. 00, fig. 67a), dated 1633, is signed by Sebastiano and Nicolò together, although the latter had passed away four years earlier.[6] Despite having trained in Genoa, Roccatagliata became a thoroughly Venetian sculptor. He transformed the classical style of Sansovino and the more vibrant, mannered idiom of Alessandro Vittoria into an easily accessible, almost airy language. His saints are utterly human, and his approach to their depiction is almost genrelike. His trademark putti, perhaps his most successful and charming creations, are not so much angels as adorable little boys with plump but still graceful bodies, chubby-cheeked faces, and masses of tightly coiled curls.[7]

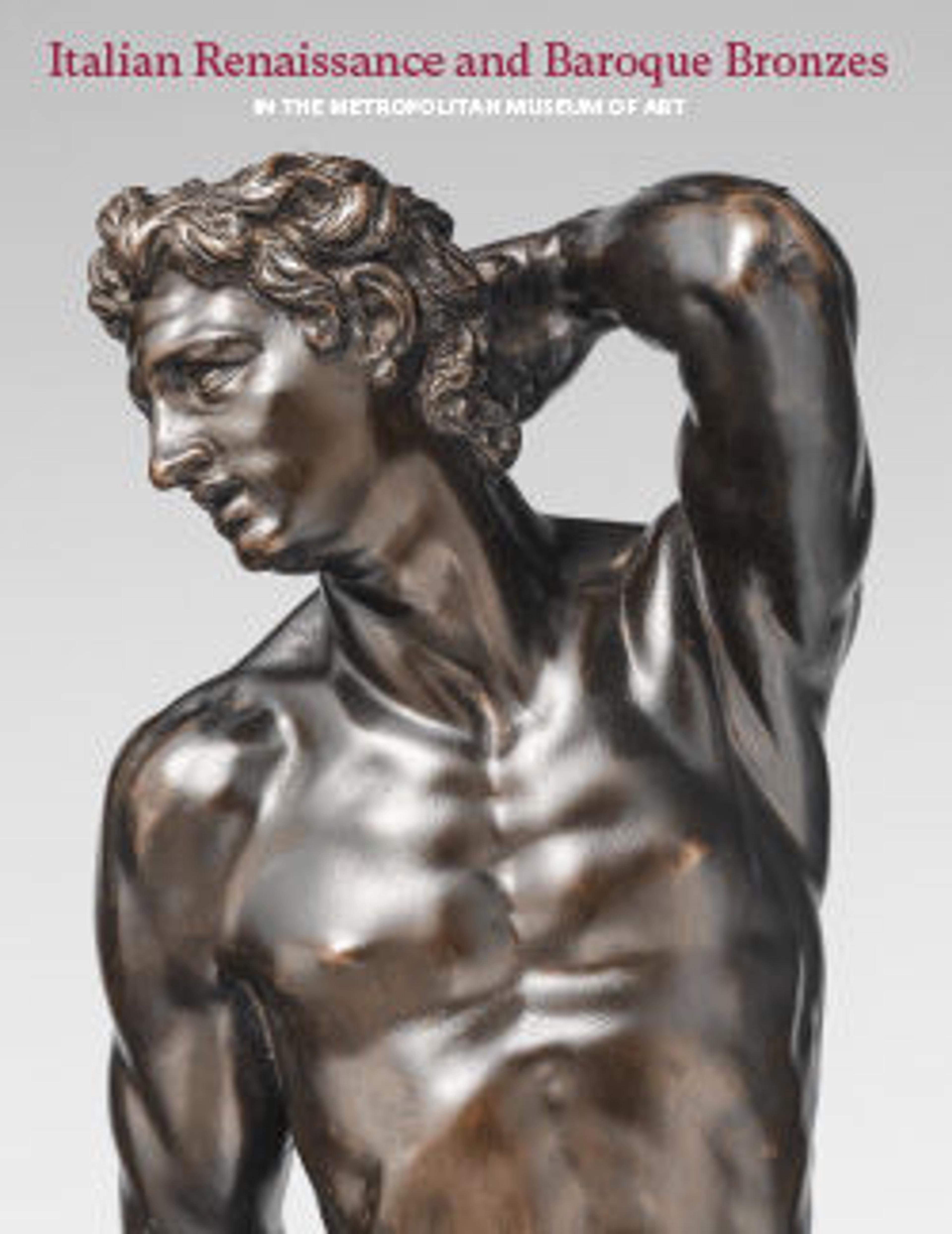

Despite having trained in Genoa, Roccatagliata became a thoroughly Venetian sculptor. He transformed the classical style of Sansovino and the more vibrant, mannered idiom of Alessandro Vittoria into an easily accessible, almost airy language. His saints are utterly human, and his approach to their depiction is almost genrelike. His trademark putti, perhaps his most successful and charming creations, are not so much angels as adorable little boys with plump but still graceful bodies, chubby-cheeked faces, and masses of tightly coiled curls.[8] The Christ Child sitting on our Madonna’s lap is a perfect example of that endearing type. Another tiny representative of the breed peeks out from under the Virgin’s veil in the shape of a cherub, one of those heavenly beings who consist only of a head and wings. Soprani observed that Roccatagliata was particularly adept at the quick modeling of wax and could render a perfect little head with a few strokes of his tool. This is apparent when looking at Christ’s face, in which the delicate nose, mouth, and chin seem to have been formed by just gently pushing together the puffy cheeks.

In many depictions of the Madonna, the child rests awkwardly in her arms: she seems to present Christ rather than to hold him. Our boy, who is old enough to sit by himself, is balanced on his mother’s right thigh and tenderly secured with a natural gesture of familiarity. The Virgin herself appears relaxed and sits on the edge of a support that looks more like an architectural element or socle than a piece of furniture. She wears a simple dress and a cloak that drapes over her legs in deep, sharply defined folds. The garments spread out over the rectangular base in a manner typical of Roccatagliata, particularly the arrangement of the hem in omega-shaped pleats. The foot of the right leg on which she carries the child juts slightly forward for greater stability, so that part of it becomes visible. Its second toe is longer than the big toe, another hallmark of the sculptor’s style.

The Virgin and Child exhibits considerably more sculptural gravitas than Roccatagliata’s Saint George and Saint Stephen, two slightly larger seated bronze figures commissioned in 1594 for San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice. This suggests that our group was made ten or twenty years later; since Roccatagliata’s secure oeuvre is small and provides little evidence for establishing a reliable chronology, it is impossible to be more precise. Furthermore, the Madonna’s appearance may be less the result of a stylistic development than of adapting a certain type that was defined in Venice by Sansovino’s regal Virgins. Roccatagliata’s Madonnas in New York and Ecouen are both more restrained and have a greater closeness to Sansovino than any of his other works. However, a comparison with Sansovino’s bronze statuette of a standing Virgin with sleeping Child in the sacristy of the Redentore in Venice highlights the marked difference between the two sculptors.[8] The head ornament on Sansovino’s figure looks like a crown, while our Madonna wears a less tidily arranged headcloth from which a sweet cherub peeks out. It was Roccatagliata’s essentially lighthearted spirit that enabled him to develop a style all his own which remained more or less consistent throughout his career.

-CKG

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Jestaz 1969, p. 81, correctly interpreted the signature as “Nicollino fecit” (not “Nicolò invenit et fecit,” as suggested by Weihrauch), and noted that Roccatagliata was indeed called “Nicolino” in the contract for the candelabra for San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice.

2. Soprani 1674, p. 89

3. Soprani 1768–69, vol. 1, p. 355.

4. See “Genova città di Maria,” at http://www3.genova.chiesacattolica.it/home_page/itinerari/00363229_Genova_citta_di_Maria.html. According to Garnett and Rosser 2013, p. 112, in the mid-nineteenth century there were 890 aediculae devoted to the Virgin in Genoa. For further references, see Lanzi 1992.

5. Kryza-Gersch 1998 and 2008.

6. For the document on Roccatagliata’s death, see Kryza-Gersch 2008, p. 272 n. 42. Until recently, the paliotto was installed as an antependium on the altar of the sacristy in San Moisè; however, as the exhibition after its restoration in the Ca’ d’Oro in 2011 revealed, it must have been conceived originally as an altarpiece. The inscription on the paliotto reads: 1633 NICOL. ET SEBASTIANVS ROCCATAGLIATA NICOLINI INVENTORES IOANNES CHENET ET MARINVS FERON GALLI CVSORES ET PERFECTORES. Jean Chenet and Marin Feron were French chasers employed by the Roccatagliatas who also cleaned the two angels on the main altar of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, modeled by Sebastiano and cast by Pietro Boselli; see Kryza-Gersch 1998, p. 118, and Kryza-Gersch 2008, p. 262.

7. Planiscig 1921, p. 595, subtitled his entry on Roccatagliata, “Der Meister des Putto.”

8. Boucher 1991, vol. 2, p. 346, no. 42, fig. 326.

Weihrauch further speculated that The Met Virgin and Child, which he considered one of Roccatagliata’s mature creations, was the same work described in 1674 by the sculptor’s biographer Raffaele Soprani as “a small figure of bronze representing the sitting Virgin with the infant Jesus on her lap . . . made by the artist with correct and harmonious proportions. And after having been dutifully cleaned by his son Simone, it was placed in a niche of marble over a door of a house in that street [in Genoa] that leads from the new Piazza delle Erbe directly to the city gate of Sant’Andrea.”[2] Soprani’s book was republished in 1768 by Carlo Ratti, who noted that the Virgin and Child had by then disappeared.[3]

It is indeed likely that The Met Virgin and Child is the same bronze to which Soprani referred. Since he reported that Roccatagliata’s work was placed above a door, such a position would necessitate a sculpture of a certain size and of a composition suited to be seen from below. Both requirements are met by our group: it is considerably bigger than a bronze destined for the private enjoyment of a collector, and both figures gaze downward. The fact that it is not modeled fully in the round but has an open back further indicates that it was intended for installation against a wall. That this must have been an exterior wall is suggested by the condition of our statuette, which seems to be the result of several layers of protective coating, typical of bronzes that have been displayed outdoors. One may thus assume that The Met’s Virgin and Child once graced the facade of a house in Genoa, which was, according to Soprani, situated in the historic city center, on today’s Salita del Prione, a winding street connecting Piazza delle Erbe and Porta Sant’Andrea, also called Porta Soprana. The Madonna was placed above the entrance door in a niche or aedicula. Such votive shrines were once very popular and could be found on practically every other corner of any European city. Very often they were devoted to the Virgin, which was particularly the case in Genoa, because the Genoese doge Ottavio Fregoso (r. 1513–15) had commanded that the insignia of foreign rule be removed from all houses and replaced with images of the Madonna, who in 1637 was solemnly ordained the official queen of the city.[4] The original setting of our Virgin and Child can thus be reconstructed fairly accurately, but we do not know when and why it was removed from the house in Genoa.

Since Weihrauch’s attribution of the Virgin and Child to Roccatagliata in 1967, knowledge about the artist has grown considerably.[5] Nicolò was born in Genoa, where he entered the workshop of the goldsmith Agostino Groppo at the age of ten or eleven. Later he moved to Venice and, together with Agostino’s son Cesare, operated a successful workshop that specialized in decorative bronzes for churches such as statuettes of saints, elaborate candelabra, and narrative reliefs. Cesare Groppo died in 1606. By 1615, Roccatagliata’s son—who was called Sebastiano and not Simone, as stated by Soprani—was effectively running the business, faithfully continuing the shop style, while Nicolò disappears from the documents, although he lived until 1629. According to Soprani, he had become blind in one eye and returned to Genoa with a friend, the wood and ivory carver Domenico Bissone. The return was not permanent, however. Roccatagliata died in Venice, where his name continued to be of good repute, as can be deduced from the fact that the so-called paliotto of San Moisè (p. 00, fig. 67a), dated 1633, is signed by Sebastiano and Nicolò together, although the latter had passed away four years earlier.[6] Despite having trained in Genoa, Roccatagliata became a thoroughly Venetian sculptor. He transformed the classical style of Sansovino and the more vibrant, mannered idiom of Alessandro Vittoria into an easily accessible, almost airy language. His saints are utterly human, and his approach to their depiction is almost genrelike. His trademark putti, perhaps his most successful and charming creations, are not so much angels as adorable little boys with plump but still graceful bodies, chubby-cheeked faces, and masses of tightly coiled curls.[7]

Despite having trained in Genoa, Roccatagliata became a thoroughly Venetian sculptor. He transformed the classical style of Sansovino and the more vibrant, mannered idiom of Alessandro Vittoria into an easily accessible, almost airy language. His saints are utterly human, and his approach to their depiction is almost genrelike. His trademark putti, perhaps his most successful and charming creations, are not so much angels as adorable little boys with plump but still graceful bodies, chubby-cheeked faces, and masses of tightly coiled curls.[8] The Christ Child sitting on our Madonna’s lap is a perfect example of that endearing type. Another tiny representative of the breed peeks out from under the Virgin’s veil in the shape of a cherub, one of those heavenly beings who consist only of a head and wings. Soprani observed that Roccatagliata was particularly adept at the quick modeling of wax and could render a perfect little head with a few strokes of his tool. This is apparent when looking at Christ’s face, in which the delicate nose, mouth, and chin seem to have been formed by just gently pushing together the puffy cheeks.

In many depictions of the Madonna, the child rests awkwardly in her arms: she seems to present Christ rather than to hold him. Our boy, who is old enough to sit by himself, is balanced on his mother’s right thigh and tenderly secured with a natural gesture of familiarity. The Virgin herself appears relaxed and sits on the edge of a support that looks more like an architectural element or socle than a piece of furniture. She wears a simple dress and a cloak that drapes over her legs in deep, sharply defined folds. The garments spread out over the rectangular base in a manner typical of Roccatagliata, particularly the arrangement of the hem in omega-shaped pleats. The foot of the right leg on which she carries the child juts slightly forward for greater stability, so that part of it becomes visible. Its second toe is longer than the big toe, another hallmark of the sculptor’s style.

The Virgin and Child exhibits considerably more sculptural gravitas than Roccatagliata’s Saint George and Saint Stephen, two slightly larger seated bronze figures commissioned in 1594 for San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice. This suggests that our group was made ten or twenty years later; since Roccatagliata’s secure oeuvre is small and provides little evidence for establishing a reliable chronology, it is impossible to be more precise. Furthermore, the Madonna’s appearance may be less the result of a stylistic development than of adapting a certain type that was defined in Venice by Sansovino’s regal Virgins. Roccatagliata’s Madonnas in New York and Ecouen are both more restrained and have a greater closeness to Sansovino than any of his other works. However, a comparison with Sansovino’s bronze statuette of a standing Virgin with sleeping Child in the sacristy of the Redentore in Venice highlights the marked difference between the two sculptors.[8] The head ornament on Sansovino’s figure looks like a crown, while our Madonna wears a less tidily arranged headcloth from which a sweet cherub peeks out. It was Roccatagliata’s essentially lighthearted spirit that enabled him to develop a style all his own which remained more or less consistent throughout his career.

-CKG

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Jestaz 1969, p. 81, correctly interpreted the signature as “Nicollino fecit” (not “Nicolò invenit et fecit,” as suggested by Weihrauch), and noted that Roccatagliata was indeed called “Nicolino” in the contract for the candelabra for San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice.

2. Soprani 1674, p. 89

3. Soprani 1768–69, vol. 1, p. 355.

4. See “Genova città di Maria,” at http://www3.genova.chiesacattolica.it/home_page/itinerari/00363229_Genova_citta_di_Maria.html. According to Garnett and Rosser 2013, p. 112, in the mid-nineteenth century there were 890 aediculae devoted to the Virgin in Genoa. For further references, see Lanzi 1992.

5. Kryza-Gersch 1998 and 2008.

6. For the document on Roccatagliata’s death, see Kryza-Gersch 2008, p. 272 n. 42. Until recently, the paliotto was installed as an antependium on the altar of the sacristy in San Moisè; however, as the exhibition after its restoration in the Ca’ d’Oro in 2011 revealed, it must have been conceived originally as an altarpiece. The inscription on the paliotto reads: 1633 NICOL. ET SEBASTIANVS ROCCATAGLIATA NICOLINI INVENTORES IOANNES CHENET ET MARINVS FERON GALLI CVSORES ET PERFECTORES. Jean Chenet and Marin Feron were French chasers employed by the Roccatagliatas who also cleaned the two angels on the main altar of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, modeled by Sebastiano and cast by Pietro Boselli; see Kryza-Gersch 1998, p. 118, and Kryza-Gersch 2008, p. 262.

7. Planiscig 1921, p. 595, subtitled his entry on Roccatagliata, “Der Meister des Putto.”

8. Boucher 1991, vol. 2, p. 346, no. 42, fig. 326.

Artwork Details

- Title: Virgin and child

- Artist: Niccolò Roccatagliata (Italian, born Genoa, active 1593–1636)

- Date: early 17th century

- Culture: Italian, Venice

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 22 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 9 3/4 in. (56.5 × 24.1 × 24.8 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1910

- Object Number: 10.185

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.