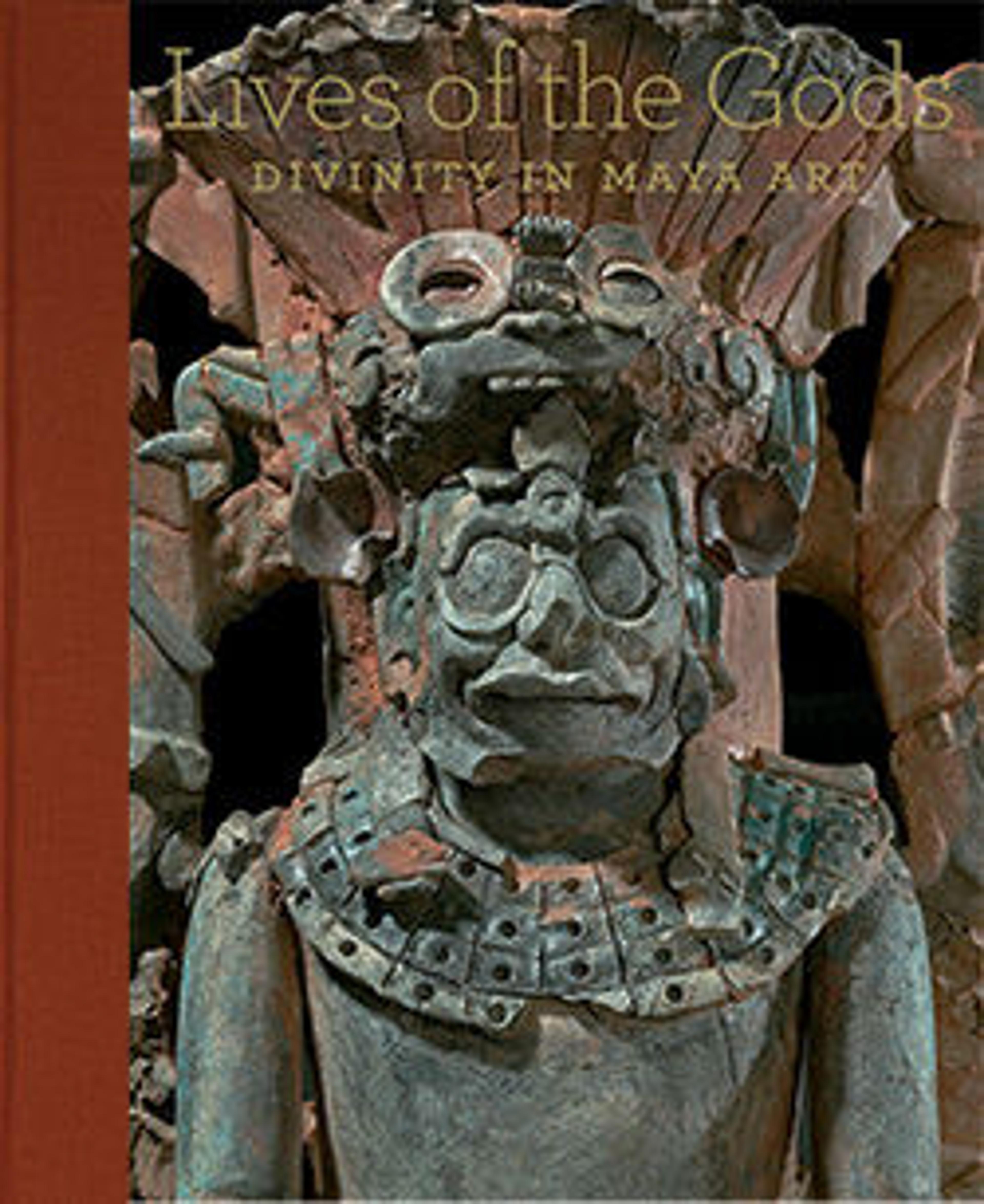

Spider monkey wearing wind god regalia

This sculpture portrays a spider monkey (Ateles geofroyi) wearing the regalia associated with the Aztec Wind God, Quetzalcoatl-Ehecatl. The monkey sits on its haunches with its legs folded on its sides with elongated toes projecting forward. The arms are raised as the monkey reaches back over his shoulders to grasp its own prehensile tail. The point of his left elbow was broken off in antiquity or in the early colonial period. Spider monkeys do not have fur around their eyes, and the artist captured this feature in the representation. The monkey’s head is tilted back and his open mouth reveals its sharp teeth. In the wild, this expression is common in aggressive behavior, and the open mouth may have been associated with Ehecatl blowing wind. The figure wears beaded wristlets, anklets, and an elaborate collar fringed with marine shells. Below the collar hangs a representation of a pectoral, likely a cross-section of a conch shell, known in Nahuatl as ehecacozcatl, or "wind jewel." Large ear ornaments, also associated with the Wind God, dangle over the monkey’s shoulders. The monkey is seated on a quadrilateral base that is scalloped, possibly alluding to the rattle of a serpent.

Across Mesoamerica, the spider monkey was an important subject for art and featured heavily in mythological scenes. Artists in the Postclassic period (ca. 900–1521) showed monkeys in stone, ceramic, and gold, with large stomachs, animated facial expressions, and attenuated tails that they often hold in their paws. In Nahuatl, the monkey is called ozomatli and is the eleventh day sign of the ancient Aztec calendar.

A stone sculpture excavated in Mexico City in 1969 and now in the Museo Nacional de Antropología depicts a dancing spider monkey wearing the mask of the Wind God, making explicit the connection between monkeys and supernatural wind. This dancing monkey also stands atop a serpent. Monkeys inhabit the canopy of tropical forests, far from the Aztec capital, but they were probably known for their speed and mischievous nature. The ornaments unearthed at the Templo Mayor in association with flint knives and spider monkey skins underscore the importance of this monkey deity in dedicatory rituals in the heart of the Aztec Empire. The monkey-Ehecatl connection may refer to part of the creation myths in which the world was destroyed by wind and the surviving human couple became monkeys.

References and Further Reading

1959 Exotic Art from Ancient and Primitive Civilizations: Collection of Jay C. Leff. Carnegie Institute. Cat. 590, p. 89.

1966 Easby, Elizabeth Kennedy. Ancient Art of Latin America from the Collection of Jay C. Leff. The Brooklyn Museum. Cat. 209, p. 42 (illustrated).

1972 Pre-Columbian Art of Mesoamerica from the Collection of Jay C. Leff. Allentown Art Museum. Cat. 59 (illustrated).

1974 Linduff, Katheryn M. Ancient Art of Middle America: Selections from the Jay C. Leff Collection. Huntington Galleries. Cat. 149, p. 119 (illustrated).

1992 Tresors du Nouveau Monde. Cat. 138 (illustrated).

2017 López Austin, Alfredo and Leonardo López Luján. Alcatraz / Huacalxóchitl: Símbolo de la sensualidad e instrumento de placer. Arqueología Mexicana XXV: pp. 18-27.

Across Mesoamerica, the spider monkey was an important subject for art and featured heavily in mythological scenes. Artists in the Postclassic period (ca. 900–1521) showed monkeys in stone, ceramic, and gold, with large stomachs, animated facial expressions, and attenuated tails that they often hold in their paws. In Nahuatl, the monkey is called ozomatli and is the eleventh day sign of the ancient Aztec calendar.

A stone sculpture excavated in Mexico City in 1969 and now in the Museo Nacional de Antropología depicts a dancing spider monkey wearing the mask of the Wind God, making explicit the connection between monkeys and supernatural wind. This dancing monkey also stands atop a serpent. Monkeys inhabit the canopy of tropical forests, far from the Aztec capital, but they were probably known for their speed and mischievous nature. The ornaments unearthed at the Templo Mayor in association with flint knives and spider monkey skins underscore the importance of this monkey deity in dedicatory rituals in the heart of the Aztec Empire. The monkey-Ehecatl connection may refer to part of the creation myths in which the world was destroyed by wind and the surviving human couple became monkeys.

References and Further Reading

1959 Exotic Art from Ancient and Primitive Civilizations: Collection of Jay C. Leff. Carnegie Institute. Cat. 590, p. 89.

1966 Easby, Elizabeth Kennedy. Ancient Art of Latin America from the Collection of Jay C. Leff. The Brooklyn Museum. Cat. 209, p. 42 (illustrated).

1972 Pre-Columbian Art of Mesoamerica from the Collection of Jay C. Leff. Allentown Art Museum. Cat. 59 (illustrated).

1974 Linduff, Katheryn M. Ancient Art of Middle America: Selections from the Jay C. Leff Collection. Huntington Galleries. Cat. 149, p. 119 (illustrated).

1992 Tresors du Nouveau Monde. Cat. 138 (illustrated).

2017 López Austin, Alfredo and Leonardo López Luján. Alcatraz / Huacalxóchitl: Símbolo de la sensualidad e instrumento de placer. Arqueología Mexicana XXV: pp. 18-27.

Artwork Details

- Title: Spider monkey wearing wind god regalia

- Artist: Mexica artist(s)

- Date: 1325–1521 CE

- Geography: Mexico

- Culture: Mexica (Aztec)

- Medium: Stone

- Dimensions: H. 15 9/16 × W. 9 1/2 × D. 10 in. (39.5 × 24.1 × 25.4 cm)

- Classification: Stone-Sculpture

- Credit Line: Gift of Brian and Florence Mahony, in celebration of the Museum's 150th Anniversary, 2017

- Object Number: 2017.393

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.