Perminangken (container for magical substances)

This container portrays an equestrian figure, which is a common theme for the carved wooden stoppers made by Toba Batak artists. This mounted figure is largely unadorned, with nose, lips, and brow in high relief. Thirteen subsidiary figures support the primary equestrian figure, who appears to be seated or crouching. The identity of the rider and the figures who support him is not known, although it has been suggested that, similar to other wooden stoppers for pukpuk containers, they represent characters from myths and legends. The horse itself has a reptilian tail curving up toward the rider’s back. In Batak mythology, the horse is linked symbolically to other creatures such as the serpent dragon and the lizard, explaining the reptilian character of the horse in this carving. In addition to their sacred nature, horses were also prestige items among the Toba Batak, for only the elite could afford them.

The equine imagery on the wooden stopper is echoed in the painted horses on the imported container, another prestige item. The blue and white ceramic was manufactured for export in the Swatow area of southern China and dates to the late Ming period (late 16th-early 17th century). Miniature jars such as this one were made in China as containers for the export of oil and ointments to Southeast Asia, where they were exchanged for local aromatics such as cloves, camphor, sandalwood, and frankincense. The wooden stopper on this vessel was then carved locally by a Toba Batak artist, and the container was used to hold pukpuk, a powerful substance made from ritually prepared human and animal remains. To enliven sacred objects such as ritual staffs and human figures, pukpuk was applied to the surface or inserted into holes in the object that were later plugged, sealing the power within.

The Toba Batak, one of six groups among the Batak peoples of northern Sumatra, live in the mountainous highlands surrounding Lake Toba (the birthplace of the Batak, according to oral histories and myths). The Batak maintained trade relations with their Malay neighbors living on the coast but otherwise remained relatively isolated until the 18th and 19th centuries when Dutch and British traders, along with German missionaries, established operations in Sumatra. Although nearly all Batak today are Christian or Muslim, they formerly recognized diverse supernatural beings, including deities, ancestors, and malevolent spirits. The primary religious figures in Batak society were male ritual specialists, called datu by the Toba Batak, who acted as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds. Much of Toba Batak sacred art centered on the creation and adornment of objects that would be used by the datu for divination, curing ceremonies, malevolent magic, and other rituals. Among the most important were ceremonial staffs, books of ritual knowledge, and a variety of containers used to hold magical substances, such as this perminangken.

References

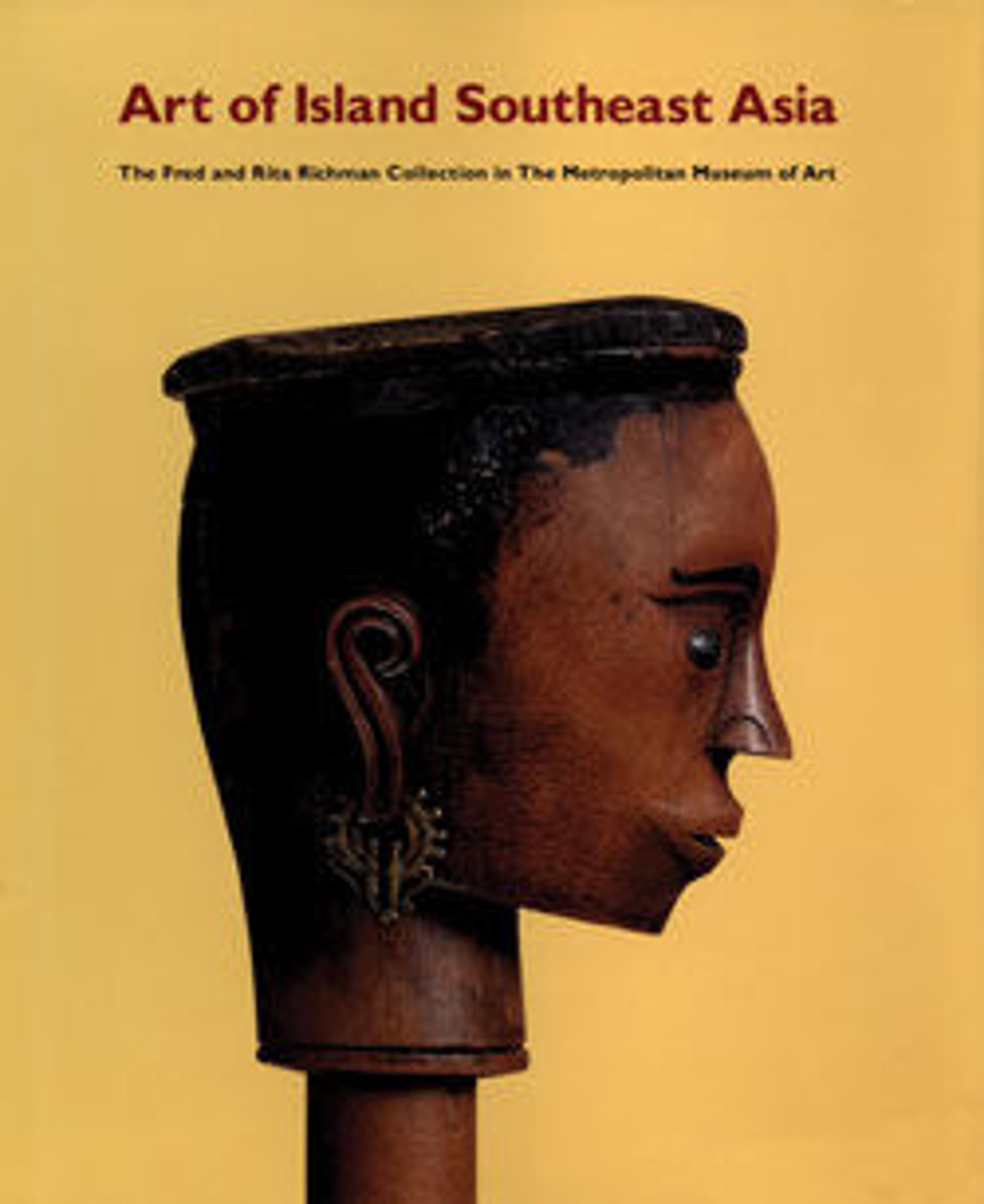

Capistrano-Baker, Florina H. Art of Island Southeast Asia. The Fred and Rita Richman Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994, pp. 48, fig. 21

Sibeth, Achim. The Batak. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991

The equine imagery on the wooden stopper is echoed in the painted horses on the imported container, another prestige item. The blue and white ceramic was manufactured for export in the Swatow area of southern China and dates to the late Ming period (late 16th-early 17th century). Miniature jars such as this one were made in China as containers for the export of oil and ointments to Southeast Asia, where they were exchanged for local aromatics such as cloves, camphor, sandalwood, and frankincense. The wooden stopper on this vessel was then carved locally by a Toba Batak artist, and the container was used to hold pukpuk, a powerful substance made from ritually prepared human and animal remains. To enliven sacred objects such as ritual staffs and human figures, pukpuk was applied to the surface or inserted into holes in the object that were later plugged, sealing the power within.

The Toba Batak, one of six groups among the Batak peoples of northern Sumatra, live in the mountainous highlands surrounding Lake Toba (the birthplace of the Batak, according to oral histories and myths). The Batak maintained trade relations with their Malay neighbors living on the coast but otherwise remained relatively isolated until the 18th and 19th centuries when Dutch and British traders, along with German missionaries, established operations in Sumatra. Although nearly all Batak today are Christian or Muslim, they formerly recognized diverse supernatural beings, including deities, ancestors, and malevolent spirits. The primary religious figures in Batak society were male ritual specialists, called datu by the Toba Batak, who acted as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds. Much of Toba Batak sacred art centered on the creation and adornment of objects that would be used by the datu for divination, curing ceremonies, malevolent magic, and other rituals. Among the most important were ceremonial staffs, books of ritual knowledge, and a variety of containers used to hold magical substances, such as this perminangken.

References

Capistrano-Baker, Florina H. Art of Island Southeast Asia. The Fred and Rita Richman Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994, pp. 48, fig. 21

Sibeth, Achim. The Batak. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991

Artwork Details

- Title: Perminangken (container for magical substances)

- Artist: Toba Batak artist

- Date: late 19th–early 20th century

- Geography: Indonesia, Sumatra

- Culture: Toba Batak

- Medium: Wood, trade porcelain

- Dimensions: H. 7 1/2 in. (19.1 cm)

- Classification: Ceramics-Containers

- Credit Line: Gift of Fred and Rita Richman, 1988

- Object Number: 1988.143.39a, b

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.