Exhibition Dates: February 13–May 21, 2017

Exhibition Location:

The Met Fifth Avenue, Galleries 691–693,

The Charles Z. Offin Gallery, Karen B. Cohen Gallery,

Harriette and Noel Levine Gallery

Press Preview:

Monday, February 6, 10 am–noon

Hercules Segers (ca. 1589–ca. 1638), the great Dutch experimental printmaker, created otherworldly landscapes of astonishing originality by using an extraordinary array of techniques that still puzzle scholars today. The Mysterious Landscapes of Hercules Segers, on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from February 13 through May 21, will be the first major exhibition in the United States devoted to the artist, who possessed one of the most fertile creative minds of his time. Although his name is not well known today, Segers’s works were highly prized during his lifetime, and Rembrandt (1606-1669) owned eight of his paintings and a printing plate.

Segers’s surviving works are extremely rare: only 10 impressions of his prints are in museums in the United States (one in The Met collection), and only 15 paintings have been attributed to the artist. The Mysterious Landscapes of Hercules Segers will feature a selection of these paintings, in addition to almost all of Segers’s prints in varying impressions. The Rijksmuseum, whose collection of Segers’s work is the largest in the world, is generously lending its entire holdings (74 prints, two oil sketches, and one painting) to the exhibition. Other European institutions, notably the British Museum and the Kupferstichkabinett of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden, will lend important works that will allow The Met to highlight Segers’s remarkable printed oeuvre in a variety of stages, revealing the range of the artist’s experiments with the etching technique, along with his idiosyncratic use of materials.

The exhibition is made possible by the Diane W. and James E. Burke Fund and The Schiff Foundation.

It is organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Hercules Segers is often characterized as a forgotten genius who was beset by misfortune during his life and died in poverty. In fact, he was a well-known painter, and his work entered numerous collections during his lifetime. The eldest son of a merchant who sold clothes and paintings, Segers was sent to Amsterdam to train with the foremost landscape painter Gillis van Coninxloo. He then joined the artists’ guild in Haarlem in 1612, at a time when that city was an important center for printmaking. In 1614 Segers moved back to Amsterdam and married Anna van der Bruggen, who was 16 years his senior and wealthy. By 1619 he bought a house in Amsterdam with a view of the incomplete North Church (Noorderkerk), which he etched around 1623. Not long afterward, in 1630, Segers faced financial difficulties and was forced to sell his house to pay his debts. Around that time, he also became active selling paintings and moved to Utrecht where he sold approximately 137 paintings, including 33 of his own. His stay in Utrecht was relatively brief, and by early 1632 he had moved on to The Hague, where he died sometime between 1633 and 1638.

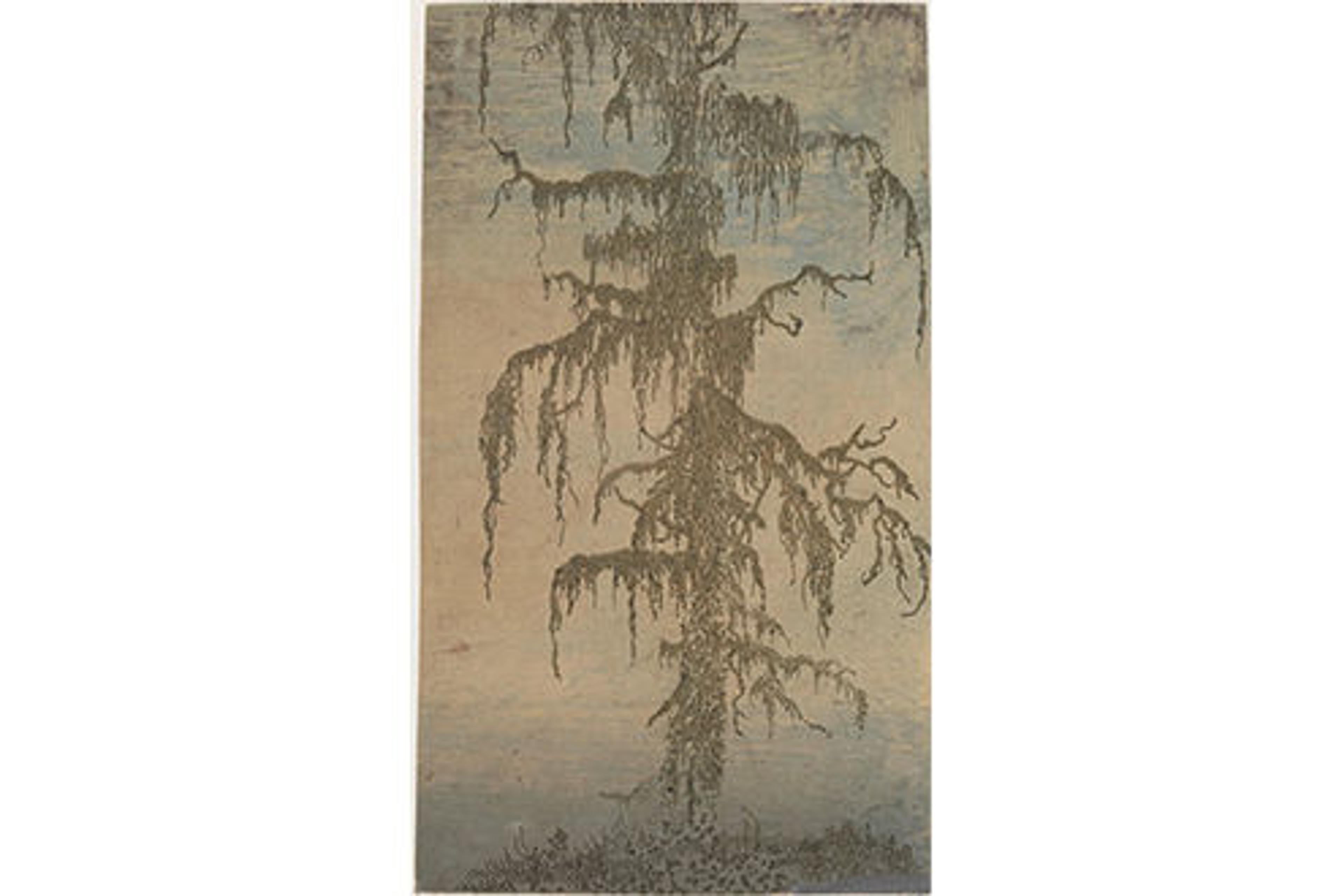

Segers probably never saw the mountains that he painted and most likely did not travel much beyond Holland, other than to Brussels. His landscapes were influenced by works by earlier artists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, but his etchings depicting rocky outcroppings resembling the surface of a distant planet, are completely original, and look like nothing else found in 17th–century Dutch art. Departing significantly from the traditional methods of his contemporaries, Segers rejected the idea that prints from a single plate should all look the same in black and white. He produced impressions in varied color schemes, painted them, then added lines or cut down the plate, turning each impression of his evocative landscapes into miniature paintings that were ahead of their time. He also painted the paper and fabrics on which he printed, created etchings in colored inks, used two printing plates to define a single image, and painted on top of impressions. He invented techniques, most notably lift-ground etching, that were not used for another 150 years.

Rembrandt, a contemporary of Segers, owned eight paintings by the artist as well as one of his printing plates, and drew inspiration from Segers for some of his own experimental prints. During the organization of this exhibition, it was discovered that Segers owned a painting by Rembrandt, making it possible to imagine that the two artists discussed art together.

Segers’s highly experimental approach to printmaking has given him a cult following among modern and contemporary artists. His works appear so much out of their time that filmmaker Werner Herzog incorporated details of Segers’s landscapes in a piece—titled Hearsay of the Soul—that he created for the 2012 Whitney Biennial.

The Mysterious Landscapes of Hercules Segers is organized by Nadine M. Orenstein, Drue Heinz Curator in Charge of the Department of Drawings and Prints at The Met.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue published by the Rijksmuseum.

Related programs include a Sunday at The Met on March 19 at 2:00 p.m. with artist Terry Winters joining exhibition curator Nadine Orenstein for a conversation about the work of Hercules Segers; and an event on Friday, May 19, at 5:00 p.m., The Mysterious Prints of Hercules Segers, featuring Huigen Leeflang, curator of the Rijksmuseum’s Hercules Segers exhibition, Nadine Orenstein, and artist Craig Zammiello.

Education programs are made possible by the Netherland-America Foundation and the Embassy of the Kingdom of The Netherlands.

The exhibition is featured on the Museum’s website, as well as on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter via #HerculesSegers.

The Rijksmuseum’s version of the exhibition, Hercules Segers, was on view there from October 7, 2016, through January 8, 2017.

# # #

Updated February 3, 2017

Image: Hercules Segers, (Dutch, ca. 1590–ca. 1638). The Mossy Tree, ca. 1625-30. Lift ground etching printed in green, on a light pink ground, colored with brush; unique impression. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; on loan from the City of Amsterdam, collection Michiel Hinloopen (1619–1708), 1885.