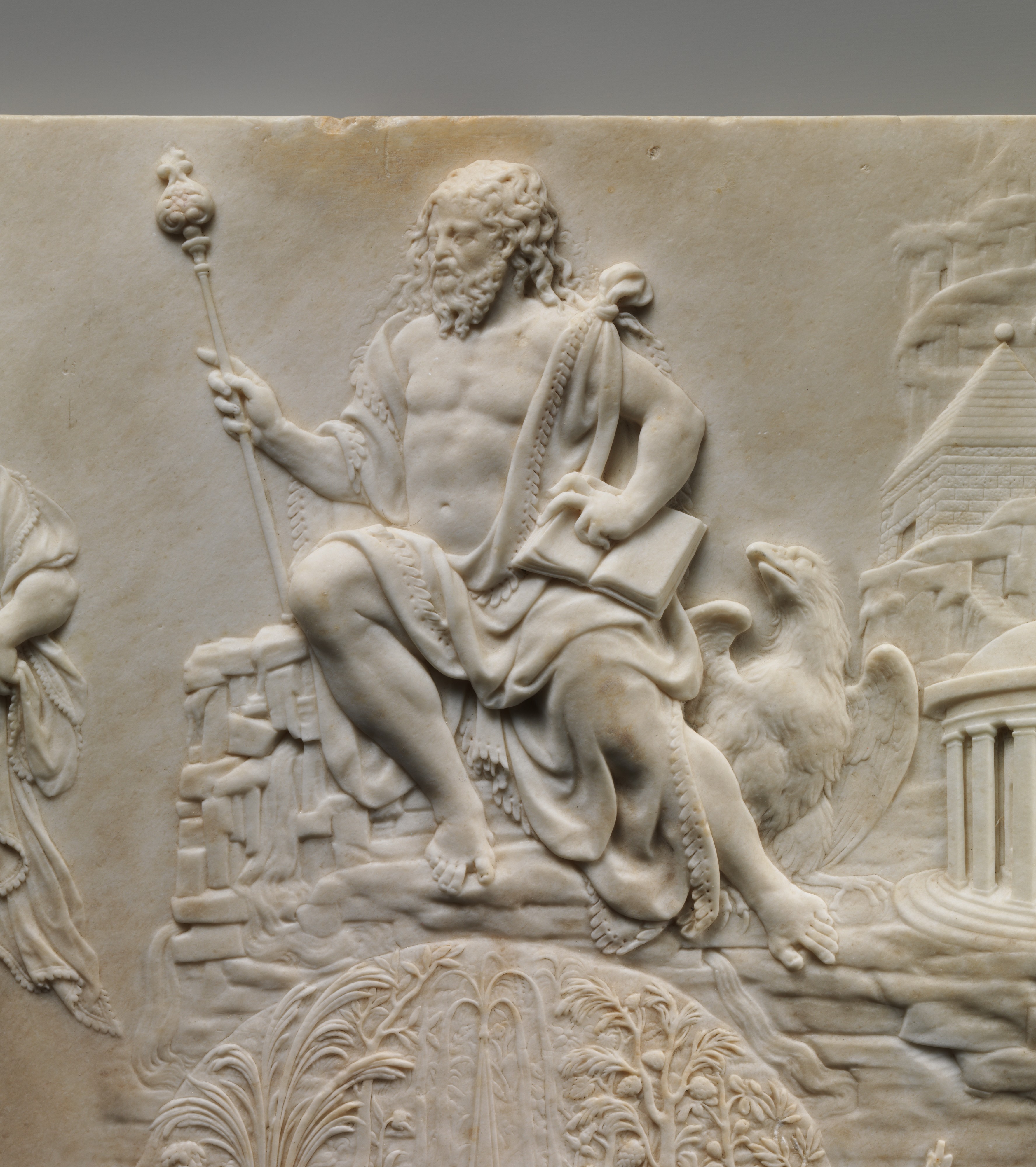

The Reign of Jupiter

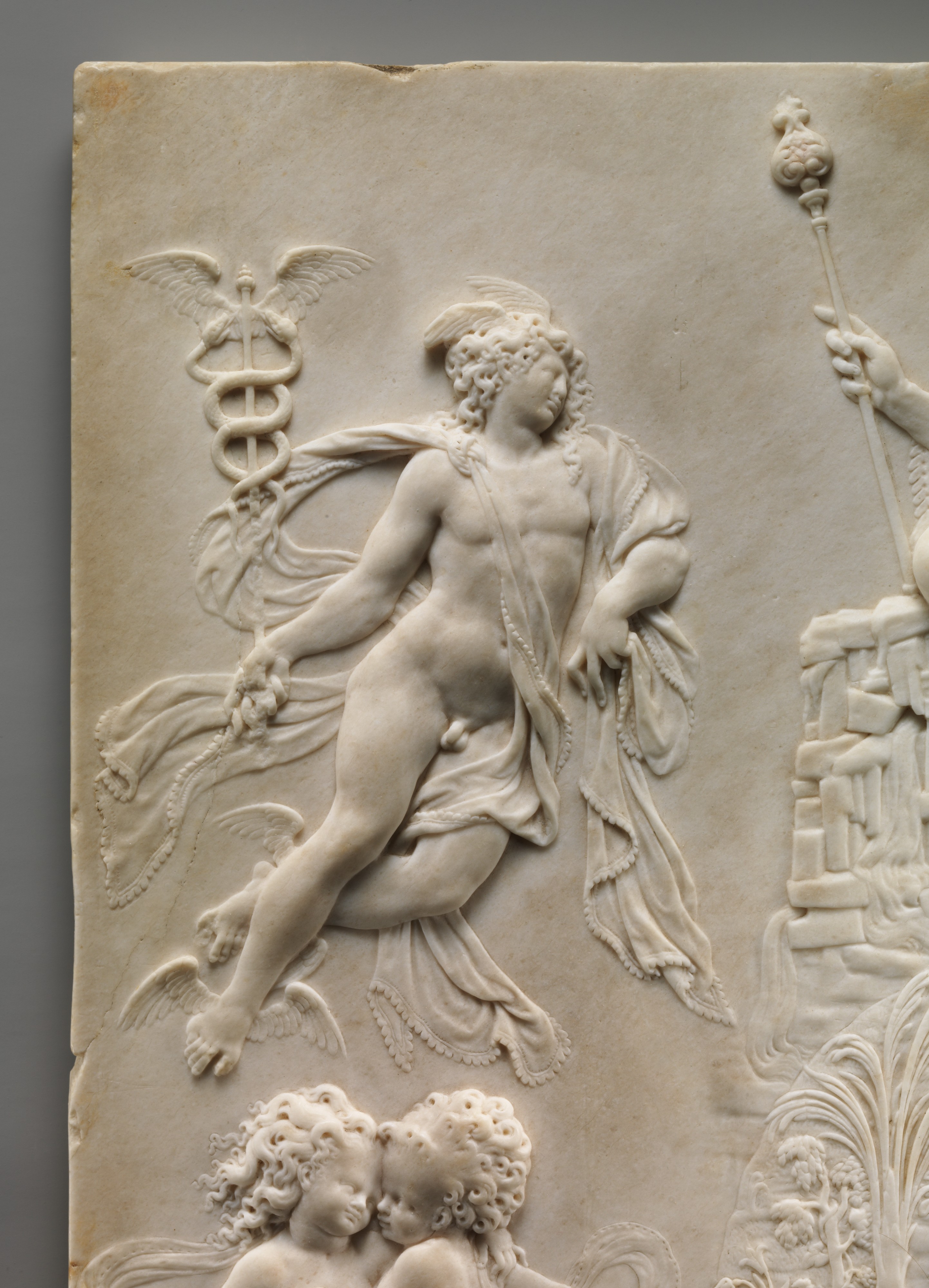

This sophisticated relief, adroitly carved and freighted with meaning, reflects the French Renaissance in all its charm and mystery. Six discrete scenes fill the rectangular marble slab, three above and three below. Jupiter occupies the prime position at top center. Accompanied by his eagle, he sits on a rocky ledge, holding — unusually for this Roman god — a scepter and a book. From his blocky throne emerge three streams, which seemingly but not physically flow down into a disklike image of a fountain in a forest. Elaborately decorated, this watery scene features dolphins supporting a basin, from which rises an obelisk. The setting is ideal, rather than untamed nature or a garden. One spots a palm tree as well as deciduous trees. To Jupiter’s right, the figure of the god Mercury with a carefully delineated caduceus flies toward the chief Olympian, seeming to engage him in speech. Below Mercury, a pair of naked children embrace. The upper right section of the relief represents an ideal city with a circular temple in front of finished and ruined buildings. Below, a bow-wielding male centaur rears toward the center.

The graphic quality of this relief raises the possibility that the sculptor followed a drawn model or models. In the French Renaissance, painters such as Francesco Primaticcio and architects such as Jean Bullant routinely furnished drawings to sculptors for tombs or building facades. The lack of fluid connection between the parts of this relief makes one wonder if the sculptor assembled drawings and prints from different sources, possibly following the verbal program of a poet or writer. The circular depiction of a fountain in the forest, for instance, could be an excerpt from an illustrated book. It is reminiscent of woodcut illustrations in the Venetian Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published in France in 1546.[1] The ideal city recalls paintings and drawings by Jean Cousin.[2] The prevalence of such themes in graphic and painted work of the 1540s and 1550s supports a dating about that time.

The elegance and fluid carving of the low-relief figures have led scholars to suggest that they are by one of the foremost sculptors of the period, perhaps Jean Goujon or Germain Pilon. Yet neither of those artists seems to have been responsible. Instead, it resembles most closely the work of the unidentified carver or atelier employed about 1549 – 52 at the chapel of the Château d’Anet, south of Paris. The elongation of the figures, the courtly gestures of the embracing putti, the swirling patterns of drapery in the air around them, and the emphasis on decorative pattern are all traits shared by the Anet chapel reliefs and this small marble. The air of courtly refinement and delight in decorative pattern bring to mind the famous Diana of Anet (ca. 1549, Musée du Louvre, Paris), a monumental fountain figure supported by a brilliantly patterned sarcophagus-shaped pedestal.

The unusual combination of figures and emblems on the relief has invited varied interpretations, of which Michael Mezzatesta’s is the most comprehensive and carefully considered.[3] The embracing infants and the centaur are seen by Mezzatesta and others as the zodiacal signs of Gemini and Sagittarius. They may refer to the birth date of a specific person, though Mezzatesta reads them as a conjunction of constellations arranged by Jupiter to coincide with poetic inspiration, as signified by the fountain between them. Mercury is the messenger god of eloquence and the arts. Mezzatesta equated him here with Charles, cardinal of Lorraine, a statesman famous for his eloquence, and the figure of Jupiter with King Henry II. In his view, the whole relief is connected with the cardinal’s now-destroyed Grotte de Meudon outside of Paris, a site of poetic and artistic inspiration about which Pierre de Ronsard and others wrote.

In another analysis of the Museum’s marble tablet, Colin Eisler relates it to emblematic reliefs seen on contemporary heart monuments (sculptures accompanying the burial of a human heart), such as the one dedicated to Francis I at the cathedral of Saint-Denis, that emphasize the role of the arts in our creative nature.[4] In Eisler’s view, the dimensions, quality, and iconography of the present relief all indicate that it was designed for use on a French royal heart monument. Although there is no documentary evidence to support the idea, he wonders whether it was commissioned for Charles IX (who died 1571 and for whom no such memorial is known) and suggests the possibility that Jacquiot Ponce carved it. While these are tempting suggestions, there is little evidence to support this work’s connection with a heart monument. Ponce’s stuccowork — which is all that remains to testify to his relief style — shows little affinity with this marble relief. The rabbeting of three edges — the bottom edge has been recut — indicate that the relief was intended to be framed and thus was probably meant to be set into a monument or into the fabric of a wall. What can be said for sure of this exquisitely carved marble is that it must have been intended for a particular location, and surely for a noble if not a royal complex; that it followed a specific program, most likely suggested by a poet or writer; and that its motifs and style suggest a date of about 1550 – 70.

[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 21, pp. 71–73.]

Footnotes:

1. See Henri Zerner. L’Art de la Renaissance en France: L’Invention du classicism. Paris, 1996, fig. 320.

2. See, for example, Cousin’s Children Playing among Ruins (1540 – 70, Musée du Louvre, Paris); ibid., fig. 272.

3. Michael P. Mezzatesta. "The King, the Poet, and the Nation: A French Sixteenth-Century Relief and the Pléiade." In IL 60: Essays Honoring Irvin Lavin on His Sixtieth Birthday, edited by Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, pp. 227–52. New York, 1990.

4. Colin Eisler. "Fit for a Royal Heart?: A French Renaissance Relief at the Metropolitan Museum of Art." Metropolitan Museum Journal 38 (2003), pp. 145–56.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.