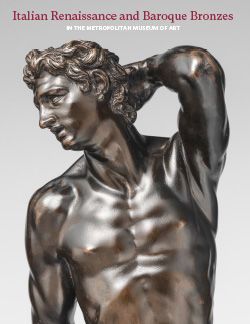

Jupiter Ammon

Not on view

The Romans considered the revered North African oracle Ammon an embodiment of Jupiter, and referred to this syncretic dual divinity as Jupiter Ammon. Identifiable by its horns and prominent beard, this head representing Jupiter Ammon was likely made to evoke an ancient fragment, though the tightly coiled horns are smaller than in surviving antique examples.[1] Cast directly, the bronze now has a dark brown natural patina with traces of a presumably original black coating in recesses.2 Most of the detail was worked into the wax, with little evidence of subsequent tooling.

Matters of dating and geography remain conjectural, though there are some clues. The unsophisticated casting technique, wherein the core was likely modeled directly on an armature removed through a rectangular opening on the top of the figure’s head, point to an early date.3 The black coating is similar to other early northern Italian bronzes. The iconography resonates with Riccio’s production, including his Moses with the horns of Ammon, and the four Jupiter Ammon heads on the base of the Paschal Candelabrum (p. 00, fig. 13c).4

The work entered the The Met in 1924 as part of the first large group of bronzes given by Ogden Mills, who had purchased it from the influential Cubist art historian, collector, and dealer Léonce Alexandre Rosenberg.5 For Rosenberg and his Cubist circle, the idiosyncratic deity with spiraling horns held special appeal. In his memoir, the painter Amédée Ozenfant designates August 26, 1931, “The Day of Spirals” and records Rosenberg’s fascination with the shape.6 Ozenfant continues: “I feel inclined to sing the praises of the spiral . . . Ammonites and horns of Jupiter Ammon; curls of women’s and of children’s hair . . .”7

-JF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. See, for example, the Imperial marble bust dated ca. 120–160 A.D. in The Met, 2012.22.

2. R. Stone/TR, December 7, 2007.

3. Ibid.

4. See the rich analysis by Alexander Nagel in Allen 2008a, pp. 134–43, cat. 7, with discussion of northern Italian antique and Renaissance examples at p. 137 n. 3.

5. Hôtel Drouot, Paris, June 12–13, 1924, lot 109: “Petite téte en bronze patiné: Jupiter, les cheveux ceints d’une bandelette, avec corne de bélier. Italian, fin du XVIe siècle. Base en marbre. Haut, 10 cent.”

6. Ozenfant 1939, p. 151-52.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.