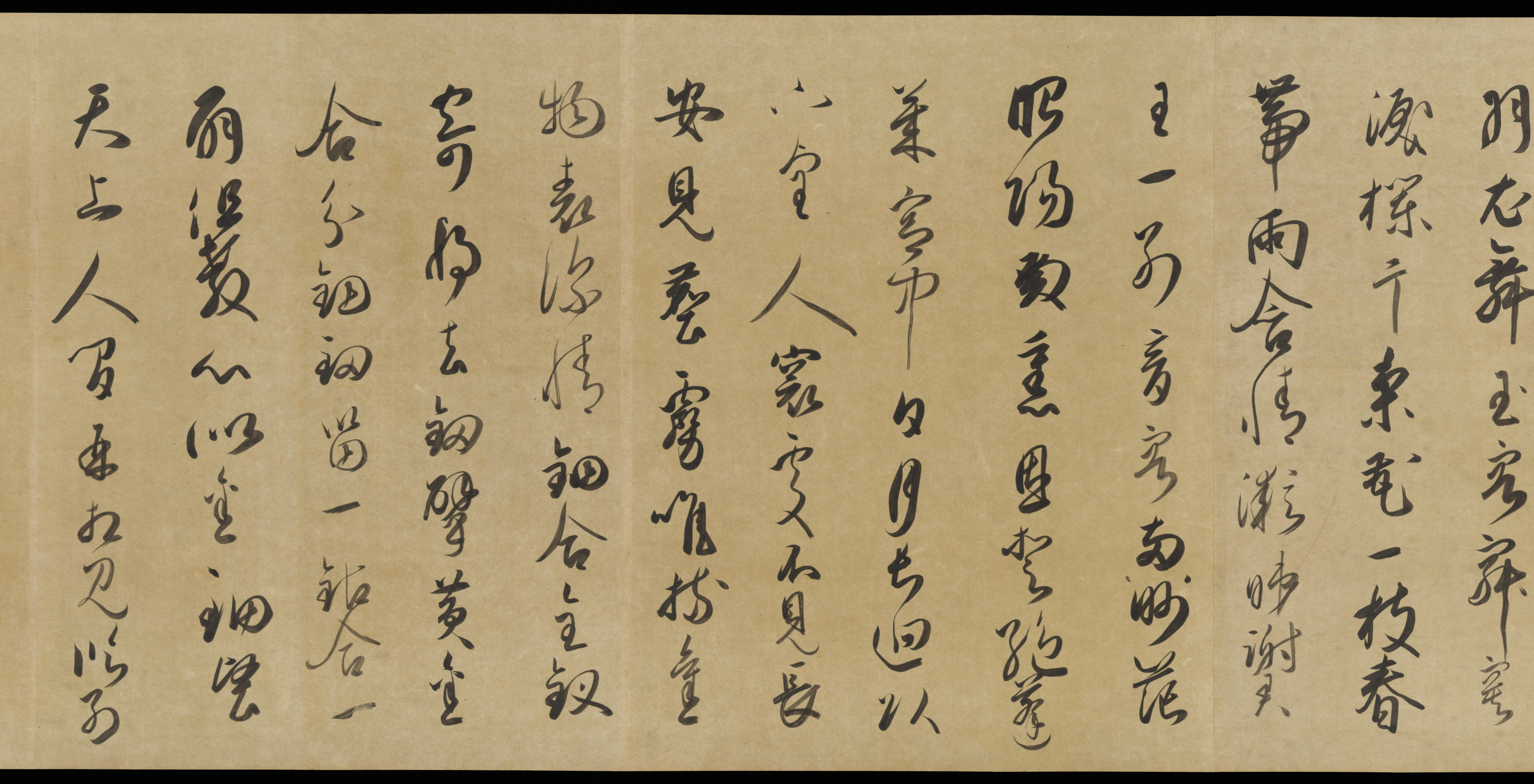

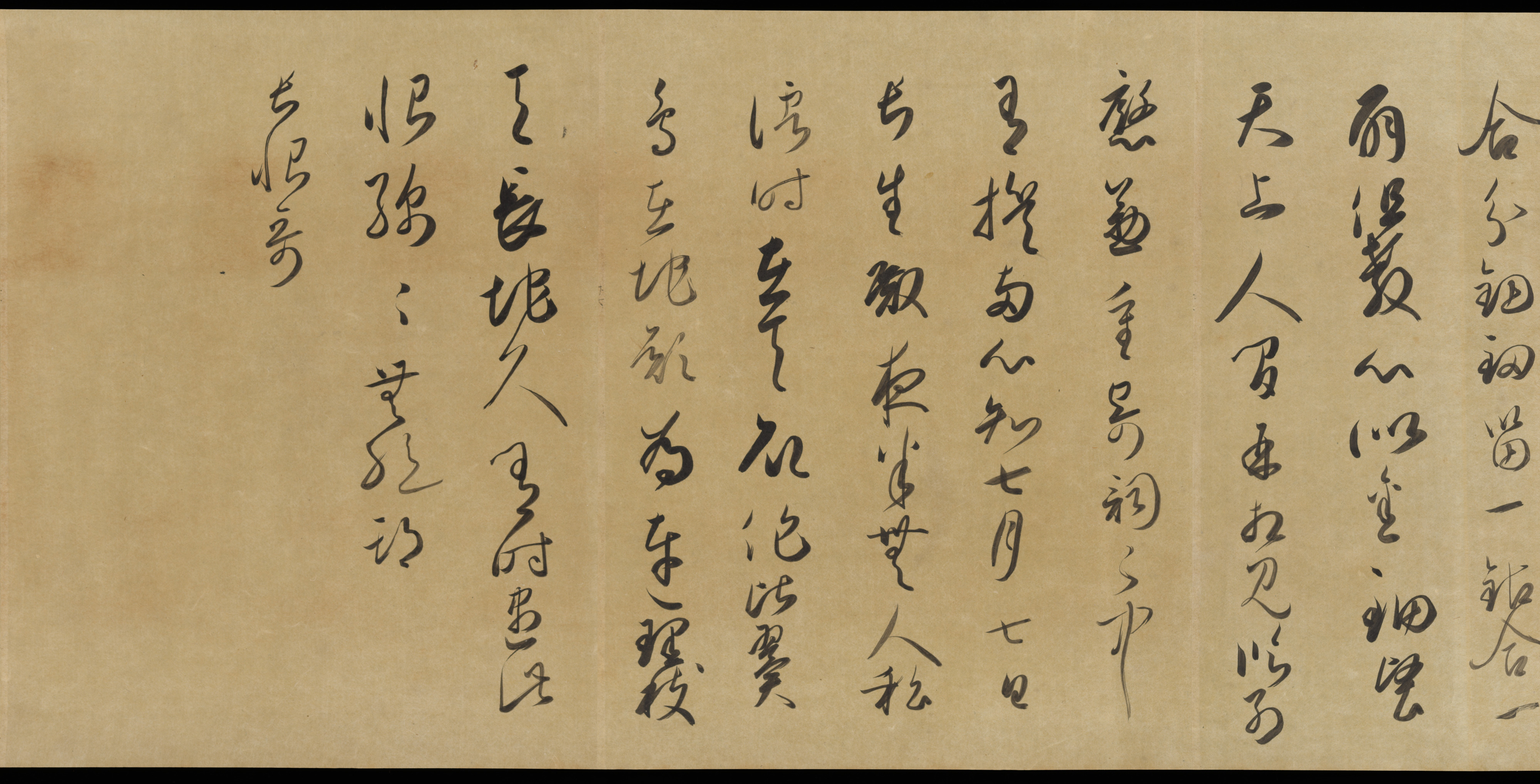

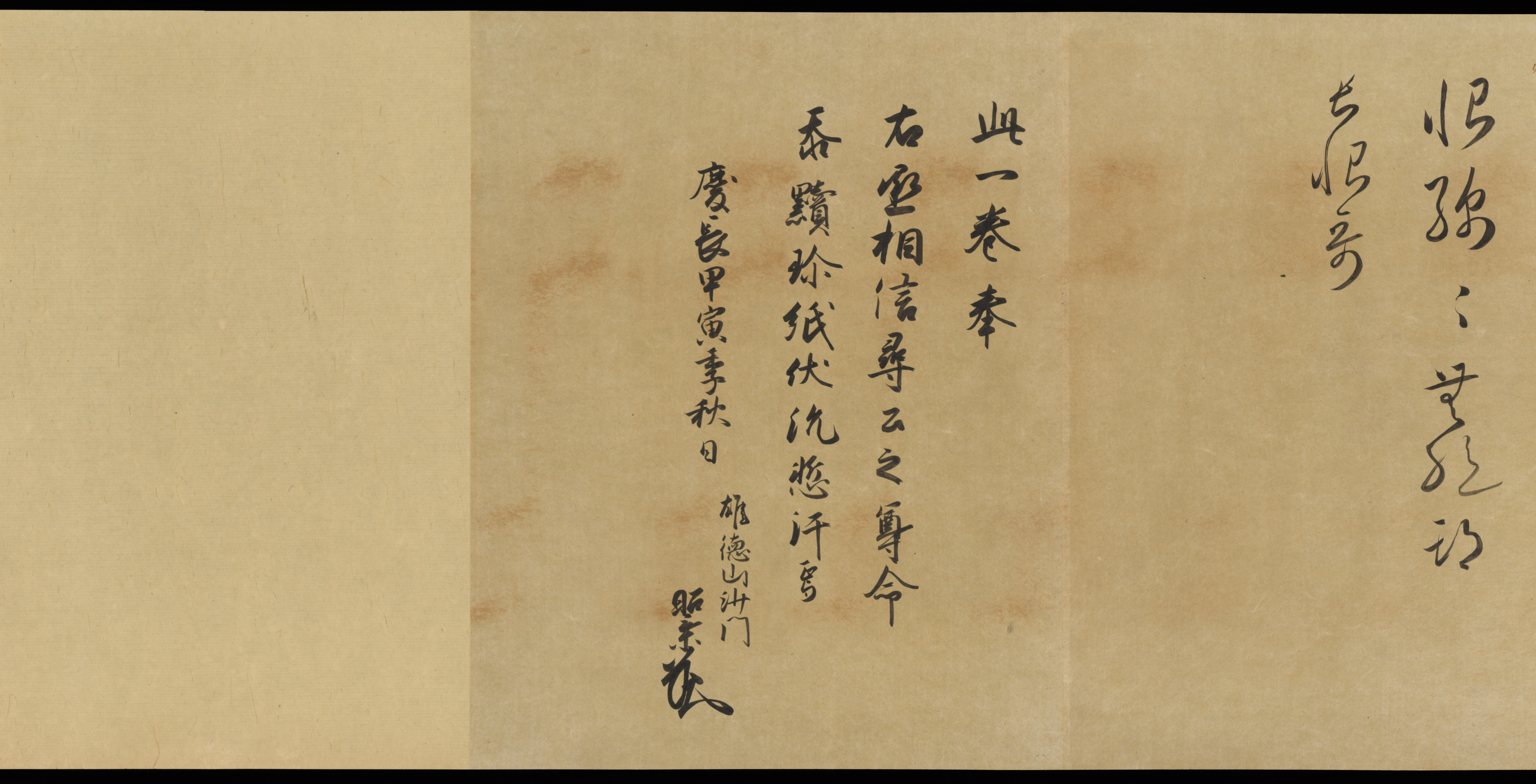

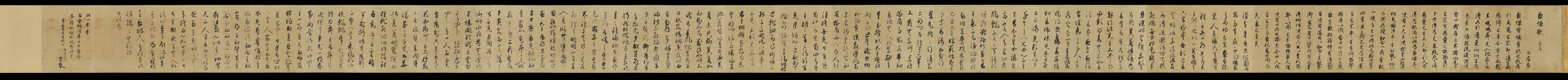

Freehand copy of a transcription of “The Song of Everlasting Sorrow” by Bai Juyi

After Shōkadō Shōjō Japanese

Not on view

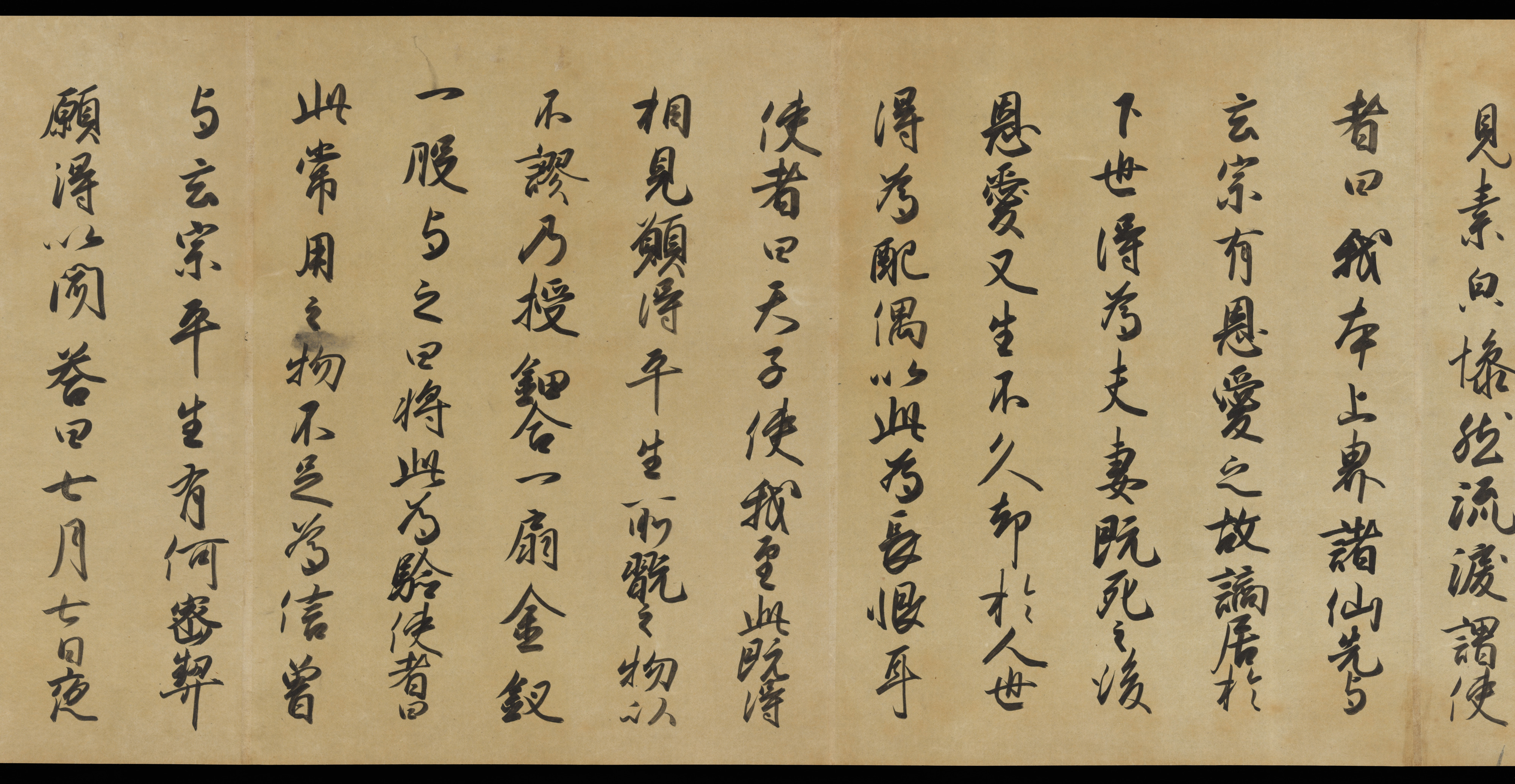

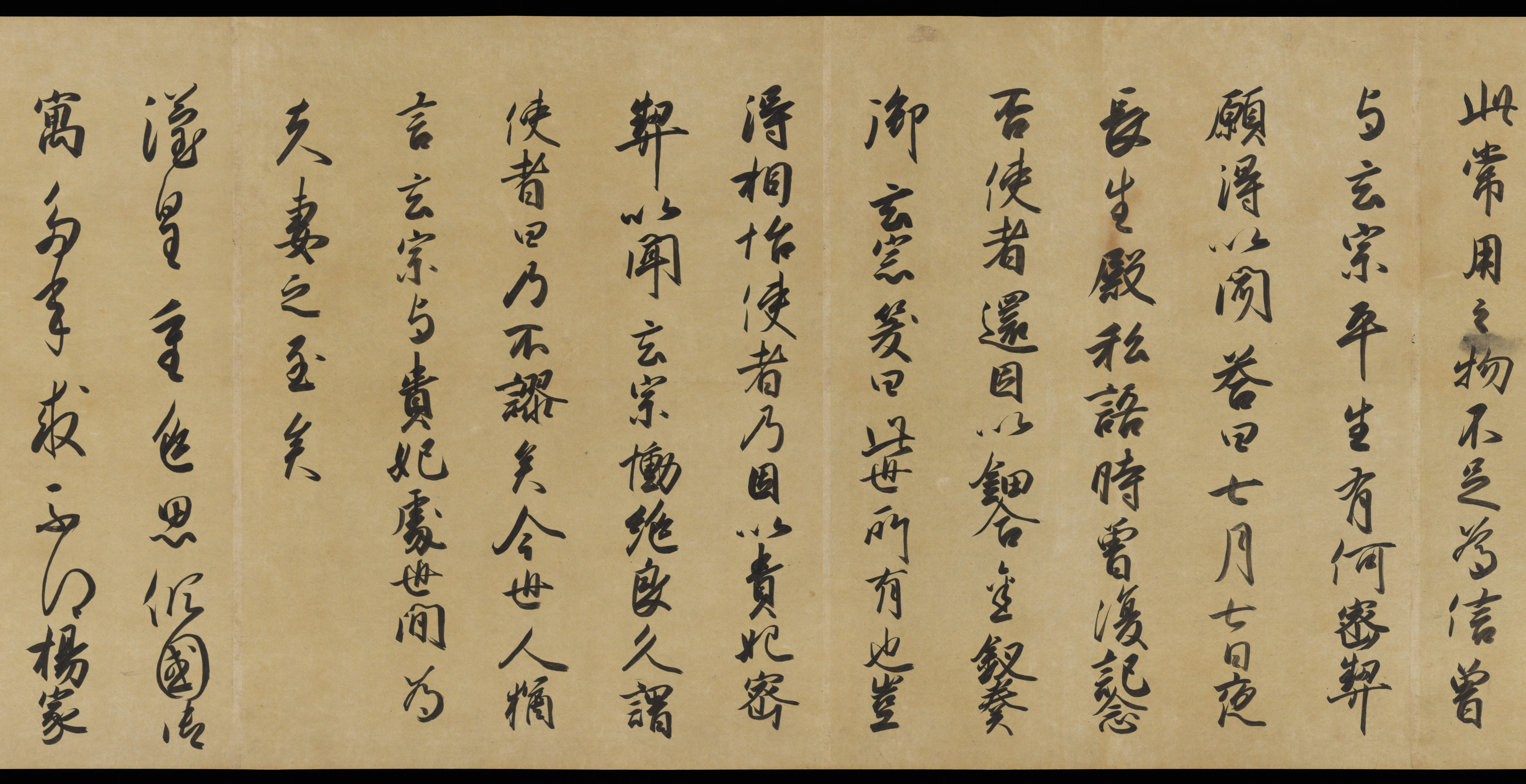

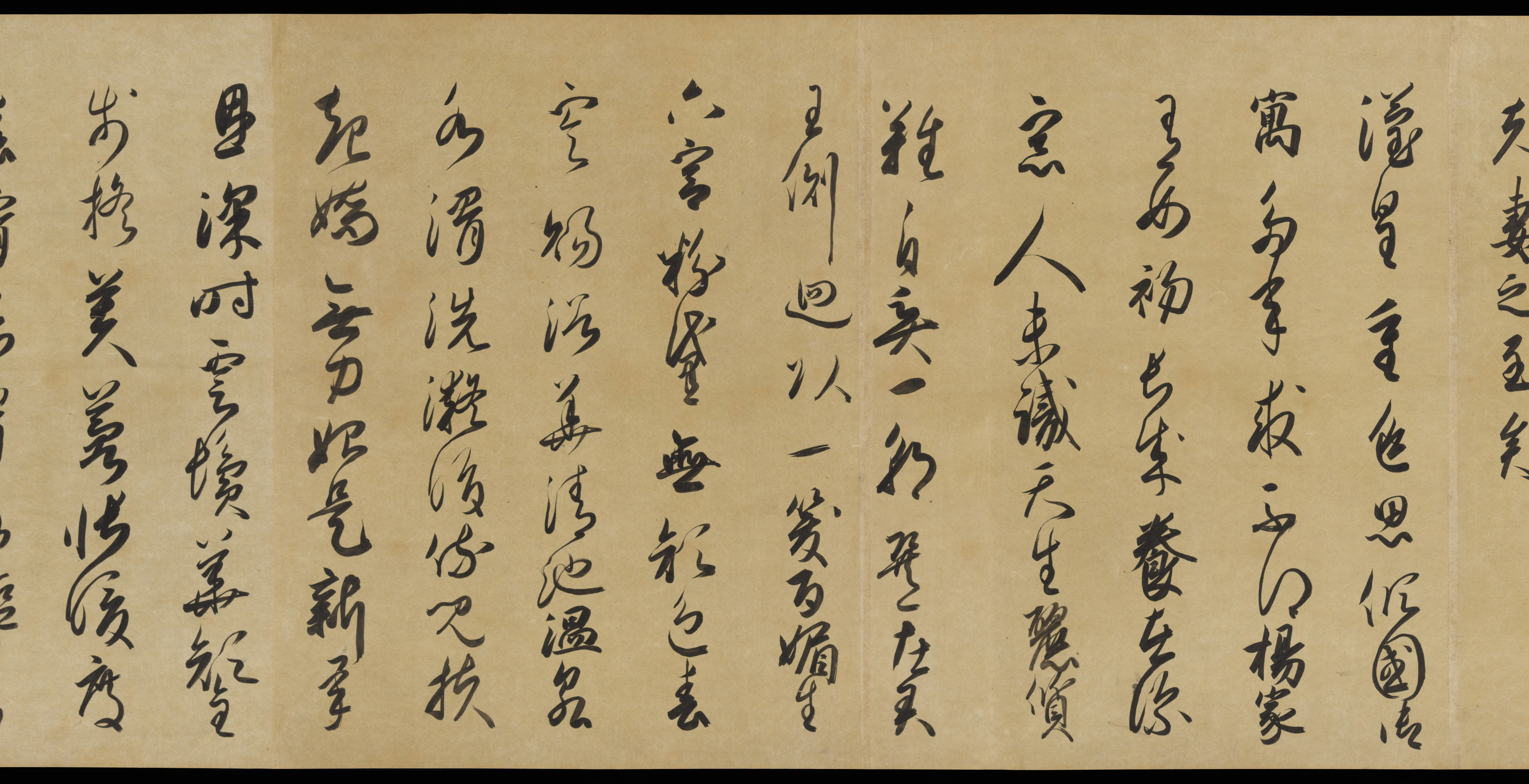

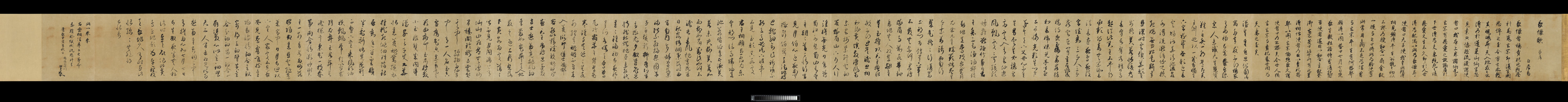

This handscroll of calligraphy, over seven meters in length, is a remarkably faithful copy of an early seventeenth-century transcription of “The Song of Everlasting Sorrow,” one of the most revered poems in East Asian literary history, composed by the renowned Tang-dynasty poet Bai Juyi (Bo Juyi, 618–907) in 806. Over 800 years later, it was transcribed by Shōkadō Shōjō, one of the most revered calligraphers of the Momoyama period, and then dedicated by him in the colophon to prominent courtier-calligrapher Konoe Nobuhiro 近衛信尋 (1599–1649). In this way, the original calligraphic composition encapsulated a sweeping history of cultural transmission from China to Japan, and served as a time capsule revealing the florescence of calligraphy and poetry during the early seventeenth century in Kyoto. This remarkable copy, which was done freehand (no doubt with some initial tracing) is hard at first glance to distinguish from the original (now preserved in Tokyo National Museum), and must have been done by an expert calligrapher with access to the original. Some scholars have speculated that the courtier, tea master and esteemed calligrapher Konoe Iehiro (1667–1736)—who was famous for his expert copies calligraphic exemplars of the previous generations—might have created this copy in the early eighteenth century, but further research is required.

The monk-calligrapher Shōkadō Shōjō is counted—along with Hon’ami Kōetsu and Konoe Nobutada—as one of the “Three [Great] brushes of the Kan’ei period,” in this case referring to the early seventeenth century. Shōjō was his Buddhist name he received in his youth. He served the Konoe family of nobles during the time the great courtier-calligrapher was the head, and thus availed himself of models of courtly calligraphy. At the same time, he was on close terms with Zen monks at the Rinzai temple Daitokuji, so his brush writing style imbibed a more dynamic, brusquer manner under that influence. He was also active in tea ceremony circles in Kyoto of the day, keeping in mind that tea gatherings were often the occasions that scrolls and calligraphy albums were shared among connoisseurs. In 1627, he became the head monk of a small temple called Takimoto-bō, and a decade later retired to a small hut in the temple precincts that he called the Shōkadō 松花堂, or the Pine Flower Hall, which also became the art name by which he is best known.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.