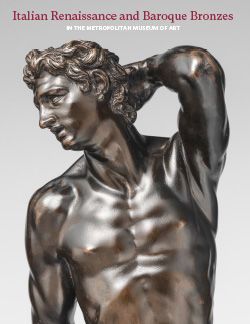

Tabernacle door with the risen Christ

Cast by Pietro Paolo Nardi

Not on view

The Risen Christ, hand resting gracefully on wounded chest, stands in the arch-topped niche of a tabernacle door, a chalice at his feet. A large shroud encircles the elegantly posed figure, covering his loins, billowing out behind, and curving around the small keyhole at his right. Incised at the bottom of the frame is a crest and ladder, a device that has been tentatively identified as the coat of arms of the Scala family of Florence (scala in Italian = ladder).[1] It might have been the device of Bartolomeo Scala (1430–1497), chancellor of the Florentine Republic.[2] Tabernacle doors of the same type can be found in Santi Simone e Guida, San Michele Visdomini, and Santo Spirito on the Corbinelli Altar, all in Florence.

Our door has a rectangular companion, first published in the 1916 auction catalogue of objects brought to the U.S. from the Davanzati Palace, Florence, by Elia Volpi (fig. 157a), and subsequently acquired by Charles C. Dent.[3] They are linked by the similarity of the Christ figures and the presence of the ladder crest as well as a signature, apparently that of the caster. The Met door is signed “Pietro Pavlo/Romano” at the lower left corner (fig. 157b), the Dent version “Pietro Paulo Nardi o Mancino Romano 1522” on the bottom edge of the frame. Mancino probably refers to the artist’s left-handedness.

Two sixteenth-century medalists were nicknamed Romano—Pietro Paolo Tomei and Pietro Paolo Galeotti—but do not fit the bill, as the style of our door is incompatible with that of either.[4] The actual Nardi remains a shadowy figure. A Pietro Paolo Nardi, “ottanoro” (caster and brassworker), is documented in Rome in 1650, providing a lamp and other metal works for the church of Santa Maria Regina Coeli (no longer extant).[5] It seems more than coincidental that this convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns funded by Anna Barberini was under the governance of the monastery of Santa Maria della Scala, whose emblem may well have been a ladder.[6] Which brings us to the knotty issue of the 1522 date on the Dent bronze. It is of course plausible that two sculptors with the same name worked a century apart, but it is much more likely that only the later Nardi existed. The sole documentation for the existence of the earlier Nardi is the date inscribed on the Dent door, which may have been misread (its present location is unknown so it was impossible to inspect), and one wonders if “1622” was misread as “1522.” A sixteenth-century date can reasonably be challenged on stylistic grounds as well.

The strongest support for dating both bronzes to the first half of the seventeenth century is the apparently frequent production of similar tabernacle doors during that time in Florence. Of particular interest is the door on the Corbinelli Altar. The altar went through at least three decorative campaigns, the first and most important under Andrea Sansovino (1490–92). A second involved Lorenzetto (1514–15), and a third is corroborated in a 1642 inscription in the altar chapel. Gabriele Fattorini has rejected Sansovino’s authorship of the tabernacle, arguing that it was added during the third phase in the mid-seventeenth century, when the chapel underwent minor renovations.[7] The tabernacle door of Santi Simone e Guida (fig. 157c), installed on a seventeenth-century altar, is almost identical to ours. Although it is possible that an older door was mounted on the tabernacle, it is more likely that both were produced at the same time, lending support to the dating of our door to the seventeenth century. Unfortunately, the door in Santi Simone e Guida is covered with a brass foil, and it is impossible to determine if, as in our door, the original surface bears an inscription by its maker.

Such portelle remained popular through the Baroque era: Giovanni Battista Foggini made one in 1705 for the tabernacle of San Giorgio alla Costa, Florence.[8] Attesting to the seriality of the design, a gilt bronze Risen Christ, of the same type as our figure but lacking the door, surfaced on the art market in 2019.[9]

-FL

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Olga Raggio identified the coat of arms in 1967 (ESDA/OF).

2. On Scala, see A. Brown 1979; Baldini 2017.

3. On loan to the Allentown Art Museum until 2005, its current location is unknown. Letter from Kathleen K. Regan, dated March 12, 1985, and correspondence with Claire McRee, Allentown Art Museum, ESDA/OF. Information about the inscription on the Dent door comes from ESDA/OF.

4. For Tomei and Galeotti, see Leydi and Zanuso 2015.

5. Dunn 1994, p. 647 n 39. It is perhaps worth mentioning that a Pietro Antonio Nardi is documented in Bologna in the early seventeenth century; according to Masini 1666, he worked in Santa Maria della Carità (p. 132) and San Michele in Bosco (p. 636).

6. Dunn 1994, p. 647.

7. Fattorini 2013, p. 142, shows that since the 1930s scholars have doubted the attribution of the Corbinelli tabernacle to Sansovino.

8. Pratesi 1993, vol. 1, p. 79, vol. 2, no. 190.

9. See Renaissance France—Italie 1500–1600 (Paris: Galerie Sismann, 2021), p. 74.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.