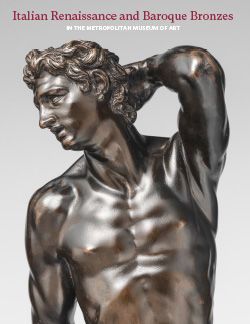

Doorknocker with a Triton and a Nereid

Not on view

This lyre-shaped doorknocker was one of the bronzes from J. Pierpont Morgan’s esteemed collection that entered The Met in 1917. It comprises a Triton and Nereid that surmount a bearded mask, their scaly bodies twisting and tapering upward. Coiled around the addorsed aquatic figures are two dragon-headed snakes who sink their teeth into their tails. A rooster with outstretched wings perches atop the term that stands between the marine couple. A visitor’s fingers would fit snugly into the empty spaces above the mask to raise and rap the doorknocker.

The popular composition has been documented since at least the eighteenth century. In 1758, the Flemish artist Giovanni Grevembroch illustrated a version in his compilation of doorknockers Battori, Batticoli e Battioli in Venezia.[1] Located at the Palazzo Bragadin near Santa Maria Formosa in Venice, Grevembroch’s doorknocker employs the same shape and figures, except the rooster is replaced by another satyr mask.

The finest cast of this type is the one sold from the Beit collection in 2007, dated to the first half of the sixteenth century and notable for its energetic modeling (fig. 71a).[2] Similar in height to the Morgan bronze, the Beit doorknocker was first published by Wilhelm von Bode, who associated it with Jacopo Sansovino.[3] It is more likely that these doorknockers were mass-market products cast by an unidentified Venetian foundry. In the city’s flourishing bronze industry, such foundries produced a wide array of functional objects from doorknockers to handbells.[4] Other versions of this composition are recorded in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Hermitage, the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum.[5] While these other casts are crowned by a mascaron, the Morgan knocker seems to be unique in its depiction of a rooster. This might be a reference to the function of the implement, akin to an alerting cockcrow. Strike-resistant and durable, bronze was a suitable medium for these resonant street-facing accessories.

The vogue for bronze knockers on palace portals emerged in the sixteenth century and merpeople became a popular subject matter.[6] In the Morgan bronze, the fish-tailed lovers’ right arms connect behind the terminal figure. This alludes to a dextrarum iunctio, representing a romantic relationship displayed fittingly at the entrance of the domicile. Moreover, these aquatic dwellers and the bronze’s anchor shape reflect Venice’s long association with the sea and her naval prowess. Located at liminal thresholds separating exterior from interior, these hybrid marine creatures remind visitors of the building’s amphibious existence in the lagoon.[7]

-AF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Grevembroch 1879, fig. 8. See Wyshak 2000, pp. 12–13, for more on Giovanni Grevembroch (Jan II van Grevenbroeck).

2. Richard 2007, p. 6.

3. Bode 1913, p. 114, no. 261.

4. See, for instance, the probate inventory of Giacomo Calderari’s foundry complex in V. Avery 2011, pp. 460–64, doc. 298.

5. LACMA, 54.51.2 (Schaefer and Fusco 1987, p. 185); Hermitage, 1783 (ibid., pp. 145–46, no. 119); Kunstgewerbemuseum, 01.224 (destroyed; Wyshak 2000, p. 84, no. 25, pl. 13, fig. 23); KHM, KK 5971 (Planiscig 1924, p. 116, fig. 198).

6. P. Brown 2004, pp. 54–56.

7. Luchs 2010, p. 181.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.