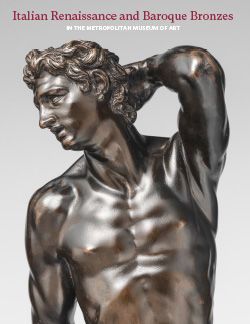

The young Hadrian

After Guglielmo della Porta Italian

Not on view

With densely curling hair, luxuriant sideburns, and a sideward movement, the bust is of an ancient type, that of the young Hadrian, initiated about A.D. 128. It is represented by marble heads in the Prado, from the collection of Philip II; the Villa Adriana, Tivoli, discovered in 1954; and elsewhere.[1] Renaissance bronze copies are in the Palazzo Reale, Naples, part of a large series of bronzes after the antique offered to Duke Ottavio Farnese by the Roman sculptor Guglielmo della Porta in 1575; the Louvre, from the collections of Louis XIV; the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich; the Hermitage; and other collections.[2] A typically literal Imperial detail is present in the Roman marbles: Hadrian’s earlobes were peculiarly creased, but there is only the barest suggestion of that trait in the later copies’ right ears.

The Munich bust has dominated the discussion because of its quality and because Hans Weihrauch ascribed it, albeit unconvincingly, to Tullio Lombardo. The others have consequently generally been called northern Italian. Bertrand Jestaz’s finding that the former Farnese properties survive and are by Guglielmo della Porta cast everything in a new light. Guglielmo’s involvement in these copies continues to surprise: we may sense some of his punctilio but nothing of his flairful linearity. On the other hand, his memo regarding the 1575 sale, quoted by Jestaz, suggests that this was purely a business arrangement, with little artistic involvement.[3]

The Met’s bust is less crisp in modeling and execution than any of the above[.4] It is not out of the question that Guglielmo and his shop issued replicas. The quality of ours seems truer to him than that of another copy, in the Palacio Real, Madrid, made under the direction of Diego Velázquez for Philip IV and attributed to Girolamo Ferrer, a Roman founder who executed the palace’s series of seven busts together with the Spaniard Domingo de la Roja in 1652 and 1657.[5] Their Hadrian wears a noticeable mustache. Ours has been deplorably treated. Three deep gouges across the nose were probably deliberate, suggesting, like the uneven splashes of “archaeological” green pigments, that an owner overstressed the design’s antiquity.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. For example, the marble in the Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri, Columbia. For the Tivoli bust, see Opper 2008, pp. 58–60.

2. Jestaz 1993, working from the document in Gramberg 1964, was able to identify most of the casts. Coraggio 1999 added the Hadrian and the so-called Servilius Ahala in Palazzo Reale, Naples, to the rest of the Farnese group. For the Louvre example, see Paris 1999, cat. 294; for Munich, Weihrauch 1956, pp. 77–78, no. 102; for Saint Petersburg, Androsov 2007, pp. 148–49, no. 158; and for additional examples, London 1966, p. 9, cat. 17.

3. Jestaz 1993, pp. 47–48.

4. The alloy is a quaternary alloy of copper, zinc, tin, and lead, with trace impurities. R. Stone/TR, 2011.

5. See Maria Jesús Herrero Sanz in Coppel et al. 2009, pp. 141–43.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.