Joseph W. Drexel and the Beginnings of the Met's Musical Instrument Collection

Jacob Hart Lazarus (1822–1891). Joseph W. Drexel, 1877. Oil on canvas; 30 1/8 x 25 1/2 in. (76.5 x 64.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Joseph W. Drexel, 1896 (96.23)

«This year the Museum officially celebrates the 125th anniversary of the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments. In 1889 Mrs. John Crosby Brown, the largest donor in the Department's history, gave the first 278 of what would ultimately be more than 3,000 instruments. She was not the founder of the Museum's instrument collection, however—that honor belongs to Joseph W. Drexel (1830–1888). This post is dedicated to Drexel, and is the first in an occasional series that will highlight the history of the collection during this anniversary year.»

Henry Louis Stephens (American, 1824–1882). Gold Fish (Francis M. Drexel), from The Comic Natural History of the Human Race, 1851. Color lithography with watercolor and gum; sheet: 7 1/8 x 11 in. (18.1 x 28 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1964 (64.629.47[20])

To escape from being drafted into Napoleon's armies, Drexel's father, Francis M. Drexel, fled from Austria and came to America, where he established a bank in Philadelphia and made a fortune. From him Joseph inherited a love of music, as well as a talent for banking and a ready-made job. Joseph himself retired from banking at the age of 46, having "acquired a vast fortune"—according to his New York Times obituary—and proceeded to spend the rest of his life pursuing his interests, primarily music and philanthropy.

Four years after Drexel's retirement from banking in 1876, the Museum's first building at 82nd and Fifth opened and the trustees now faced the task of filling it with art. One of them, William E. Dodge, knowing of Drexel's interests, wrote to Museum Director Luigi Cesnola to "cultivate Mr. Drexel, who will be a most valuable and liberal friend of the museum." The plan worked: Within a few months the Museum acquired eight paintings selected by the Museum from Drexel's collection—and prudently made Drexel a Museum trustee.

Drexel showed his interest in music by collecting musical manuscripts, serving as director of the Metropolitan Opera, president of the New York Philharmonic Society (the predecessor to the New York Philharmonic), playing several instruments—most notably the violin—and, in 1884, making a collection of musical instruments.

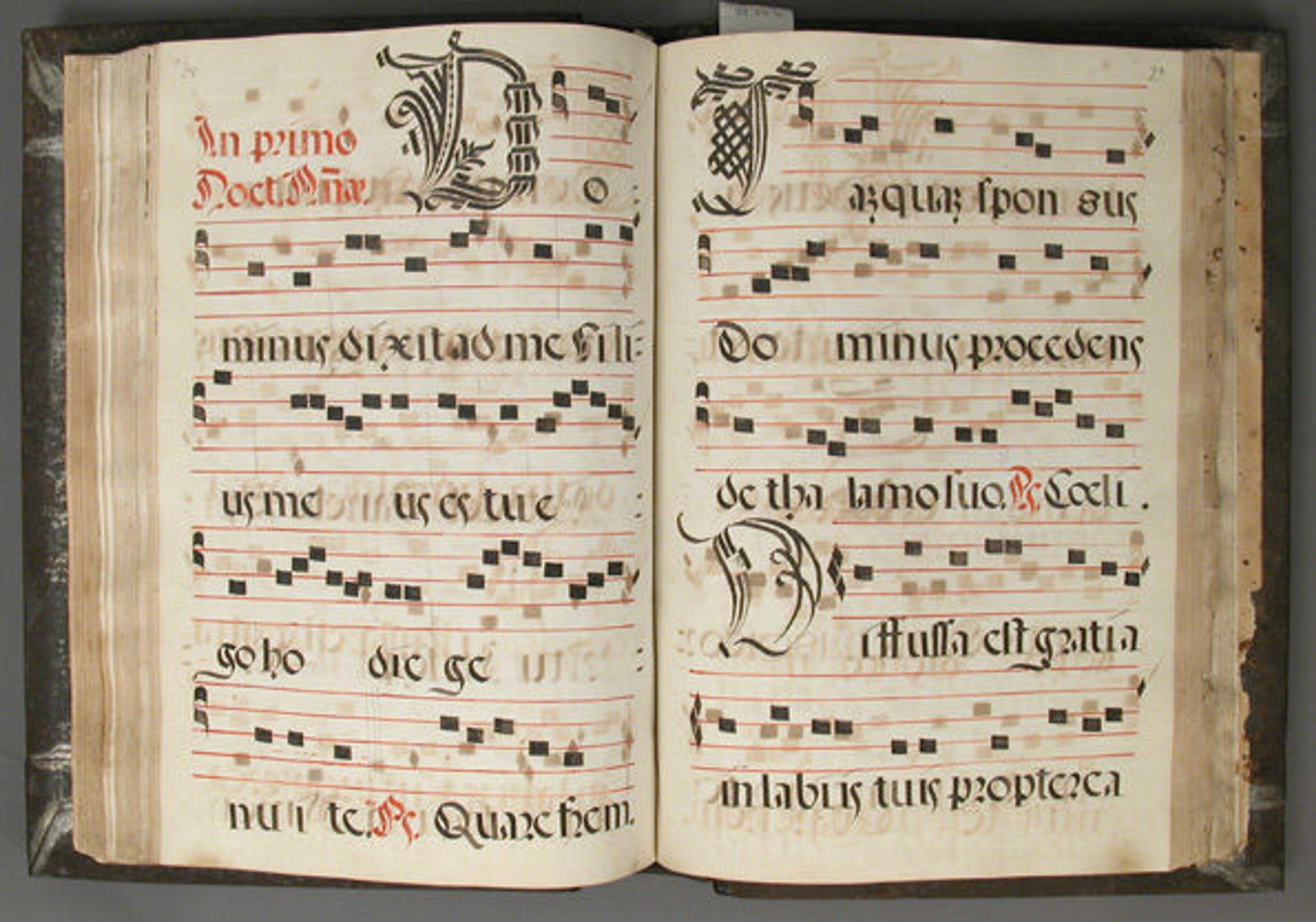

Antiphonary, 15th century. German. Tempera, ink and gold on parchment; leather binding; Overall: 18 x 11 1/4 x 3in. (45.7 x 28.6 x 7.6cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Joseph W. Drexel, 1889 (89.27.3)

Drexel's collection was specifically intended for the Met. As he wrote to Cesnola in late 1884:

While in Paris I spent some time forming a collection of old musical instruments, obsolete forms which with some I have already would fill two or three cases and, I think, be most interesting to a museum, in fact, I formed the collection for the Metropolitan Museum . . . I shall add many manuscripts from my collection . . . I will arrange the whole [exhibit] myself.

The Museum's Committee on Art Objects recommended acceptance of Drexel's offer, and Drexel kept his promise, arranging the instruments at the Museum himself before the exhibit opened to the public on November 2, 1885. The Museum's annual report for that year duly acknowledged the gift, which it described as "a large collection of ancient musical instruments . . . consisting of harpsichords, mandolins, violins, and other stringed instruments . . . " One hundred thirty years later, forty-four of them remain in the Met's collection.

Sixtus Rauchwolff (German, 1556–1619). Lute, 1596. Wood, various other materials; L. 58.4 cm (23 in.); W. 17.8 cm (7 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Joseph W. Drexel, 1889 (89.2.157)

Drexel's instruments included specimens from China, Syria, Persia, Japan, Arabia, Africa, and the United States, but the great majority were from Western Europe. He personally arranged them in the Museum's gallery dedicated to wood, which also included such diverse items as a large clock and a "fine Norwegian reindeer sledge," as the 1888 Museum General Guide advised. Alongside the instruments, as promised, he displayed psalters, antiphonaries, and other manuscripts from his collection. (These ultimately went to the Met's Medieval collection and the library.) Drexel donated a few more items over the next three years and, as a trustee, encouraged the Museum to buy one or two other instruments of importance. Joseph Drexel died on March 25, 1888, one day after playing violin in a quartet with members of the Philharmonic.

Almost as soon as Drexel made his initial gift to the Museum in October 1885, Mrs. John Crosby Brown contacted one of her friends who was also a trustee, William C. Prime, asking him to arrange for her to see the Drexel collection at the Museum. Prime welcomed Mrs. Brown and her son to visit the Drexel collection as often as they wished. Before those visits, no one in Mrs. Brown's family had a connection to the Museum, but, as a result of seeing the Drexel collection carefully displayed and appreciated at the Museum, when it was time for her to find a public home for her own collection, Mrs. Brown offered it to the Met.

She told the trustees quite specifically that she was sending them her collection because it complemented the Drexel collection. Drexel's small "seed" of forty-four choice instruments thus eventually benefitted the Met almost one hundredfold.

Rebecca Lindsey

Rebecca Lindsey is a member of the Visiting Committee of the Departments of Musical Instruments and Islamic Art.