Solace and Silence: The Music of Arvo Pärt

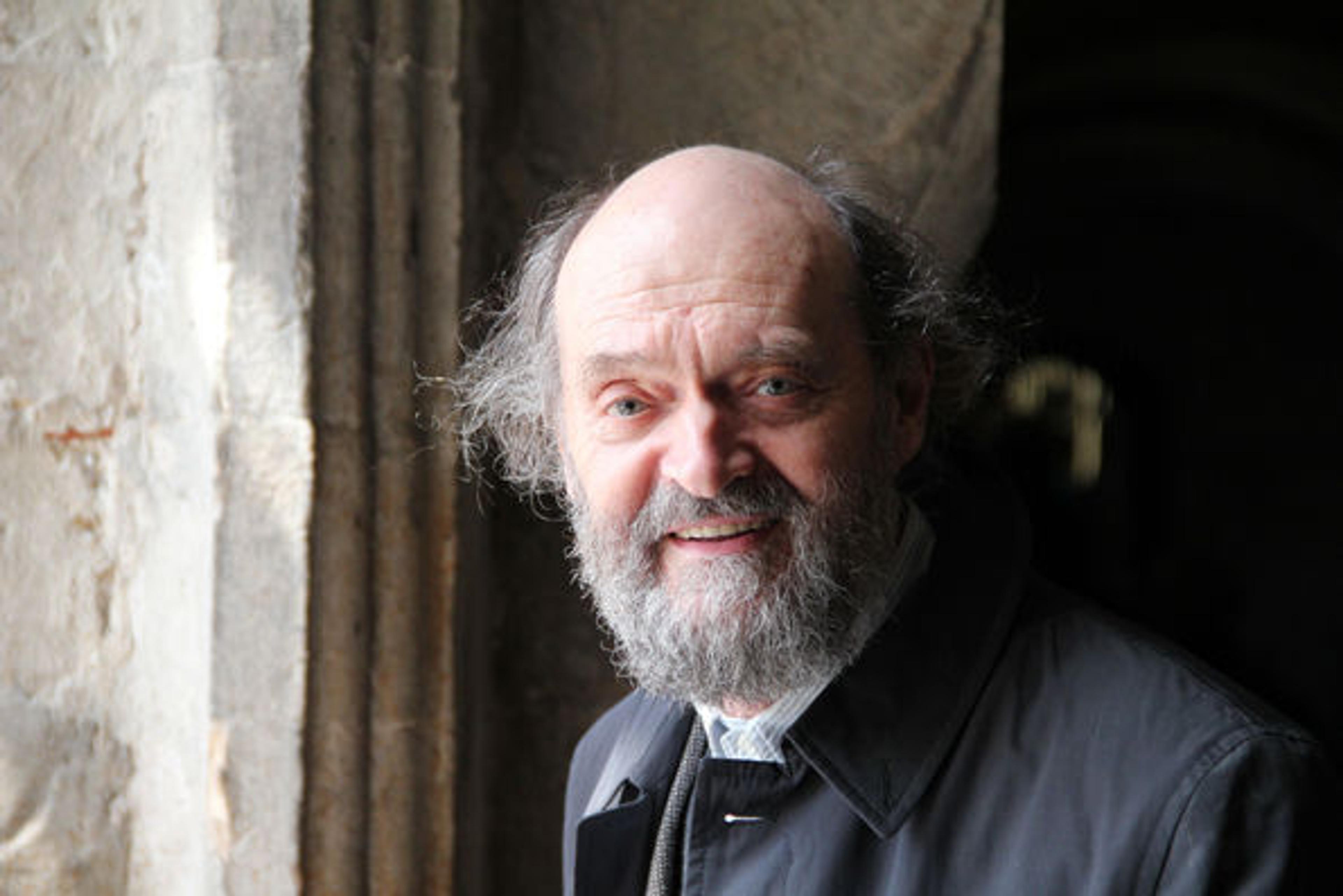

Arvo Pärt © Universal Edition/Eric Marinitsch

«"Feel the World Stand Still"

This phrase is currently emblazoned on subway ads across New York City promoting the Arvo Pärt Project at St. Vladimir's Seminary, which will bring the Estonian composer to New York for the first time since 1984. While this kind of dramatic hyperbole often surrounds any discourse regarding Pärt's music—"mystical," "heavenly," "timeless" are frequently used—the overwhelming acceptance of his work is a rare occurrence in the landscape of contemporary concert performance. His is a music that seamlessly bridges the gap between the modern and the ancient, minimalism and Gregorian chant, making the comparisons often cited between Pärt's music and that of both Phillip Glass and Josquin dez Prez the equivalent of an artist being equally heralded alongside Rothko and Caravaggio.»

Met Museum Presents is proud to bring two events of the Arvo Pärt Project to the Met in June: the sold-out Arvo Pärt in The Temple of Dendur, a performance of the composer's Kanon Pokajanen (Canon of Repentance) by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir that will be streamed live on the Museum's website and WQXR's Q2 Music; and the final installment of this season's SPARK conversation series, Spirit in Sound and Space—A Conversation Inspired by Arvo Pärt, which will bring together a panel comprising a neuroscientist, architect, and theologian to explore the spiritual content of Pärt's music and discover how the spaces in which music is performed can amplify its emotional power.

Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir © Kaupo Kikkas

With his long, unkempt beard and distance from the public eye, it is easy to paint Arvo Pärt as a solemn religious figure, a modern-day monk praying at the altar of sacred music in an increasingly secular world. However, the composer's lively demeanor and early body of work are nothing of the sort. Born and raised outside of Tallinn, Estonia, Pärt's earliest compositions were built on the twelve-tone serialism technique often associated with Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School, filled with harsh dissonances that were deemed "avant-garde bourgeois music" by the secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers in 1962. His Second Symphony even relied on a variety of aleatoric concepts, which included the musicians crinkling paper and squeezing children's squeaky toys.

Pärt quickly tired of these compositional tools during the early 1970s and remained publicly silent for several years while he explored new avenues for his music. During this time he became enchanted by Gregorian monody and early Renaissance polyphony, closely studying the intricate framework of ancient chants and the music associated with the Russian Orthodox Church, which was to become an important entity in his personal life as well.

It was at this time that Pärt began devising his compositional system of tintinnabuli—derived from the Latin term for "little bells"—which gave birth to most of the composer's best-known works, including Fratres, Tabula Rasa, Für Alina, and the Berlin Mass. A strict and purely tonal method of composition, tintinnabuli pairs a single melody line against a secondary line that simply provides harmony—ringing together, as a bell would, against a drone of the tonic, or "home," pitch of the piece. And, just as church bells ring into silence, so does Pärt use silence to startling effect in his tintinnabuli system: Not only does the silence punctuate individual phrases in his vocal music, but it provides moments of startling stasis not often associated with modern composition—a silence from which all subsequent music is born.

It is Pärt's use of silence that creates the most rapturous and chilling moments during live performances of his work, juxtaposing the thought of Eastern religion that regards silence as a mystical and spiritual tradition—a connection with oneself, the environment, and a higher power—and the Western anxiety that perceives silence as indicative of isolation, loneliness, and death. The transformative quality of these silent moments can strike one as completely strange and alien in a public forum, and even Pärt himself remarked in an interview with the New York Times that at the 1977 premiere of Tabula Rasa the concert hall "was so still that the people could not breathe or cough, it would disrupt. It was with me the same feeling. My heartbeart was so noisy that I thought everyone could hear."

So what makes this composer's music—primarily built on limited harmony, silence, and strict antique forms—so appealing to modern audiences? In a time when audiences still stampede out of concerts of "new music" and bemoan the frantic noise of modern living, Pärt remains singular among his peers in that his music reaches outside of contemporary thought and into the wide expanse of the eternal. While Pärt's music is spiritual, it is not overtly religious in application, and is equally at home in the church or concert hall, thus allowing all listeners, regardless of creed or philosophy, to find a sense of stillness and personal repose. His music allows audiences to step outside of themselves, to feel one's heartbeat drum so loudly that it becomes one with the silence itself, providing the rare opportunity to seemingly feel the world stand still.

Arvo Pärt in The Temple of Dendur on Monday, June 2, is currently sold out, but the performance will be streamed live beginning at 7:00 p.m. on the Museum's Live Stream page and at WQXR's Q2 Music.

To purchase tickets to Spark: Spirit in Sound and Space—A Conversation Inspired by Arvo Pärt, or any other Met Museum Presents event, visit www.metmuseum.org/tickets; call 212-570-3949; or stop by the Great Hall Box Office, open Monday–Saturday, 11:00 a.m.–3:30 p.m.

Michael Cirigliano

Michael Cirigliano II is the managing editor in the Digital Department.