Diana and the Stag

These two automata (17.190.746 and SL.2.2019.33.1a, b) belong to an ornate group of table ornaments that are among the most sophisticated created during the Renaissance. They both depict Diana, goddess of the moon and the hunt, who was able to communicate with and command wild animals.[2] Her power to control beasts is underlined in both objects, as her chariot—a conflation of throne and coach box—in the example from the Yale University Art Gallery (SL.2.2019.33.1a, b) is drawn by two leopards, while she is perched atop a large stag in the one from The Met (17.190.746). Silver sculptures of Diana were particularly popular among European nobility, because hunting was a feudal privilege and a primary pastime of European rulers.[3] A stag with multiple prongs on its antlers, like the mount of The Met’s Diana, was the perfect symbolic hunting trophy; just as a sovereign had exclusive rights to hunt in the lands over which he reigned, a stag with such impressive antlers would have dominated its territory. The free city of Augsburg was known for the production of silver objects, particularly those used as amusements in the courtly rituals of drinking and dining.[4] As Augsburg was a center of clockmaking, as well, its artisans specialized in automata designed to move across and around a tabletop. Both of these automata were likely used as part of drinking games at princely festivities, albeit in different ways.[5]

The goddess in the Yale collection would have driven her chariot across the table, her animal companions animated and her eyes moving back and forth in time with the ticking of the clock incorporated into her throne. She shot her arrow after the chariot stopped, and the guest in front of which it landed was obliged to finish their drink, much to the other guests’ delight. The Met’s example would have itself contained the drink: the stag’s body is hollow and its head removable, thus serving as a vessel.[6] After the lavishly decorated automaton—which includes a few paste stones added in the late nineteenth century to appeal to contemporary Rothschild taste—showed itself off to the table, the guest in front of which it stopped was obliged to empty the wine from the stag’s body by gripping the back legs firmly and lifting it off the base.[7]

Footnotes

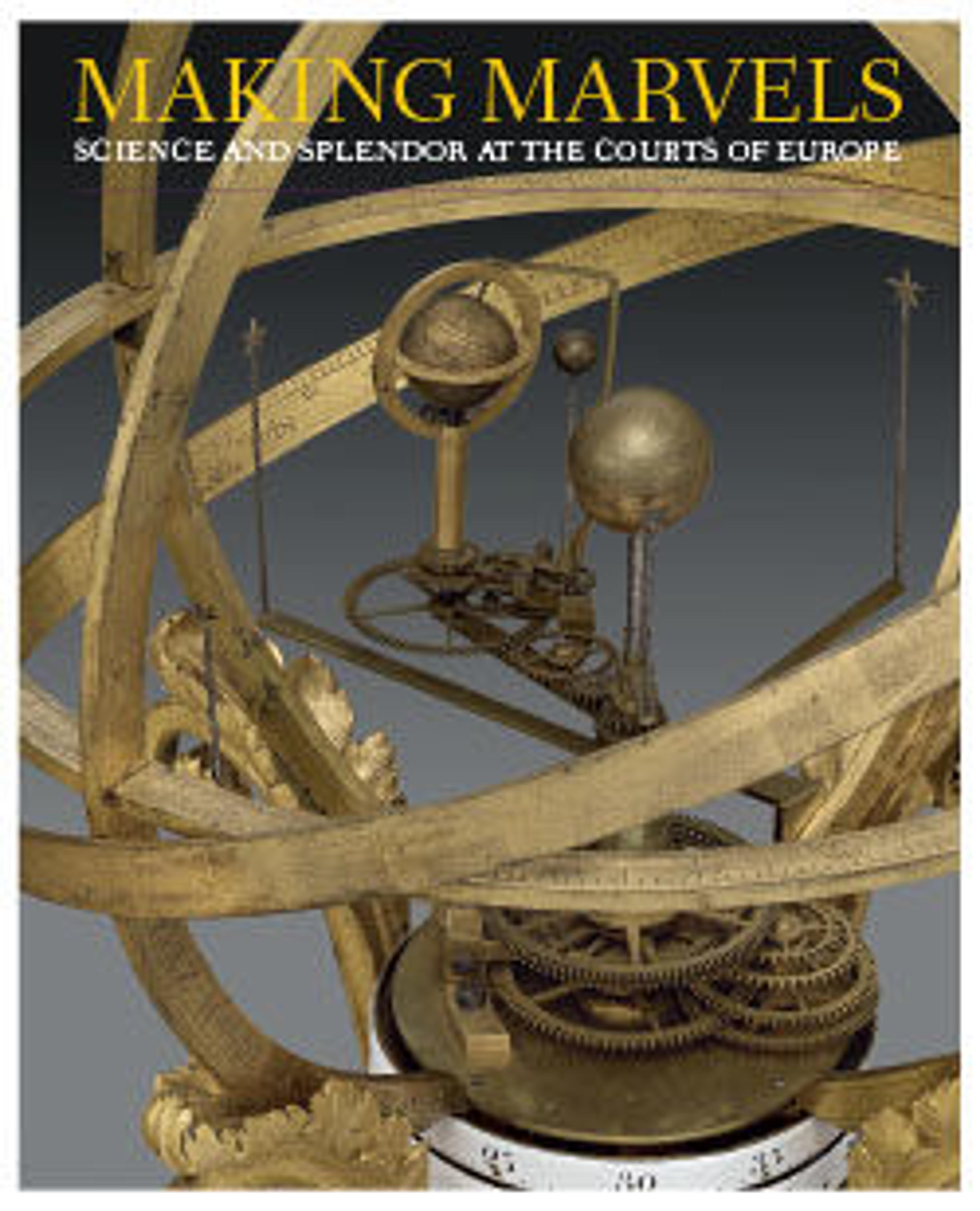

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Koeppe, Making Marvels: Science & Splendor at the Courts of Europe: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019)

1. Seling 2007, p. 41, no. 0270 (Augsburg town mark), p. 207, no. 1248g (maker’s mark).

2. Hunger 1974, pp. 106–7.

3. See Seelig 1990–91.

4. Vincent 2016, p. 78.

5. About twenty objects of the same type as The Met’s Diana are known today in various collections. See Vincent 2016, p. 78; Keating 2018, p. 98; see also Seelig 1990–91; Angelmaier 2015b.

6. See Maurice and Mayr 1980, p. 274.

7. Many thanks to Clare Vincent, Curator Emerita, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (personal communication, February 2001), for observing the late additions to this piece, which also include Diana’s crescent moon (removed), arrow, and quiver.

The goddess in the Yale collection would have driven her chariot across the table, her animal companions animated and her eyes moving back and forth in time with the ticking of the clock incorporated into her throne. She shot her arrow after the chariot stopped, and the guest in front of which it landed was obliged to finish their drink, much to the other guests’ delight. The Met’s example would have itself contained the drink: the stag’s body is hollow and its head removable, thus serving as a vessel.[6] After the lavishly decorated automaton—which includes a few paste stones added in the late nineteenth century to appeal to contemporary Rothschild taste—showed itself off to the table, the guest in front of which it stopped was obliged to empty the wine from the stag’s body by gripping the back legs firmly and lifting it off the base.[7]

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Koeppe, Making Marvels: Science & Splendor at the Courts of Europe: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019)

1. Seling 2007, p. 41, no. 0270 (Augsburg town mark), p. 207, no. 1248g (maker’s mark).

2. Hunger 1974, pp. 106–7.

3. See Seelig 1990–91.

4. Vincent 2016, p. 78.

5. About twenty objects of the same type as The Met’s Diana are known today in various collections. See Vincent 2016, p. 78; Keating 2018, p. 98; see also Seelig 1990–91; Angelmaier 2015b.

6. See Maurice and Mayr 1980, p. 274.

7. Many thanks to Clare Vincent, Curator Emerita, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (personal communication, February 2001), for observing the late additions to this piece, which also include Diana’s crescent moon (removed), arrow, and quiver.

Artwork Details

- Title: Diana and the Stag

- Maker: Joachim Friess (ca. 1579–1620, master 1610)

- Date: ca. 1620

- Culture: German, Augsburg

- Medium: Partially gilded silver, enamel, jewels (case); iron, wood (movement)

- Dimensions: wt. (without mechanism) confirmed: 14 3/4 × 9 1/2 in., 5 lb. (37.5 × 24.1 cm, 2250g)

- Classification: Metalwork-Silver

- Credit Line: Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917

- Object Number: 17.190.746

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.