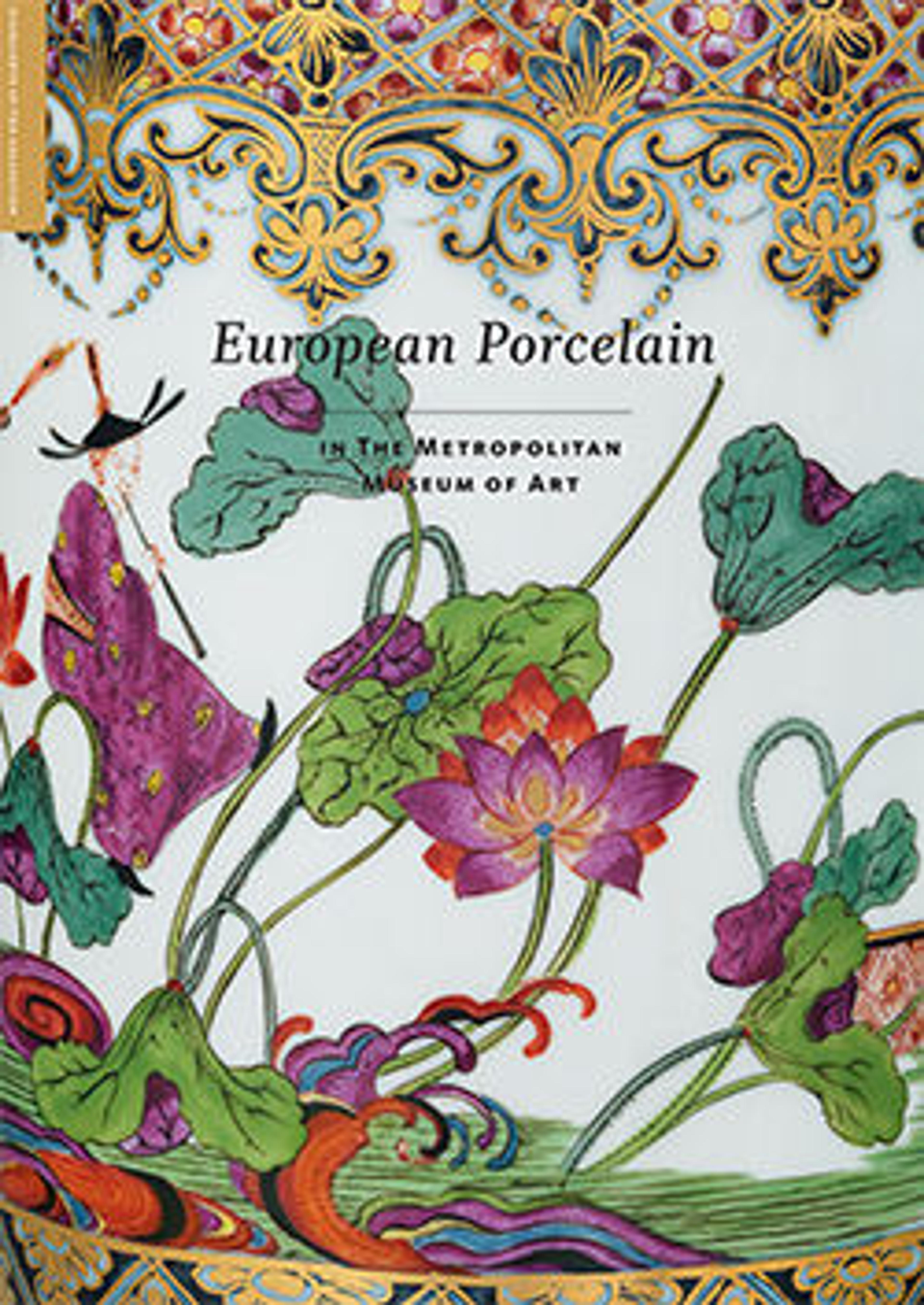

Two soldiers shaking hands

Germany witnessed a growing number of porcelain factories in different regions of the country during the mid-eighteenth century, and the circumstances of their founding often had much in common. Most of the new porcelain factories were created due to the interest of an aristocratic patron, and they relied on the financial subsidies provided by that patron to varying degrees. Typically, the technical expertise required to produce porcelain was supplied by potters who had learned their trade at another factory prior to their arrival, and workers were commonly hired away from other concerns to staff the new enterprise. The production of the factory often reflected the taste of the patron who founded it, and frequently the factory floundered financially when the patron died.

All of these circumstances applied to the Kelsterbach factory, which had its roots quite commonly in the production of faience and which struggled financially from its inception.[1] It appears a faience factory was established in Königstädten in 1758 after receiving a charter that same year from Landgrave Ludwig VIII von Hessen- Darmstadt (1691–1768), in whose domain Königstädten was located. However, the factory moved to the nearby town of Kelsterbach later that year after a change of ownership. The factory’s faience production never became commercially viable, and in 1761 the Landgrave assumed ownership just as porcelain production became the factory’s sole focus.

It appears that the requisite technical knowledge at Kelsterbach was provided by Christian Daniel Busch (German, 1722–1790), who had been employed at Meissen both as a painter and as a developer of enamel colors. Busch’s career typifies the itinerant nature of many workers in ceramic factories in the eighteenth century, because he left Meissen to work at factories in Vienna, Munich, Künersberg, and Sèvres before arriving at Kelsterbach in 1761.[2] He served as director of the Kelsterbach factory until 1764, at which time he returned to Meissen for the remainder of his career.

The modeler Carl Vogelmann (German, active 1759–84), who had been previously employed at Ludwigsburg in the years 1759–60, was hired by Kelsterbach at the outset, and while other modelers worked at the factory—notably Jakob (German, active at Kelsterbach 1763–64) and Johann Carlstadt (German, at Kelsterbach by 1764)—the majority of the figures produced by the factory are attributed to Vogelmann’s hand,[3] and seventy- five plaster molds by him were listed in a 1769 inventory of the factory.[4] His figures are characterized by their unusual and expressive faces, prominent eyes, and a certain ungainly quality to their modeling. One of the most distinctive features of his figural groups is the elaborate architectural frames in which the figures are placed. Composed of robust, highly sculptural C- scrolls, these quintessentially Rococo stage sets have as much visual presence as the figures that inhabit them.[5]

This figure group depicting two soldiers displays all of Vogelmann’s stylistic traits, as well as his predilection for unconventional compositions. The two soldiers shake hands in front of a tent that covers a small table holding a bottle, two beakers, and a plate of bread. This scene is elevated on a stand composed of large, sinuous C-scrolls; two cannons and accompanying cannonballs rest on the base. The basic composition of the group may derive from a portrait of the Austrian military commander Gideon Ernst Freiherr von Laudon (1717–1790) by the printmaker Johann Esaias Nilson (German, 1721–1788).[6] Von Laudon rose to prominence during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) due to his military successes, and Nilson has included two soldiers in the fore-ground of the portrait in poses very similar to those in the Kelsterbach group. In both the print and the porcelain group it appears that a truce is being celebrated, although no specific event has been identified that might have been the impetus for the composition. The soldiers’ costumes do not immediately reveal their identities, although it has been suggested by Helmut Nickel that the soldier in the red jacket may be a Pandour (a member of the Croatian regiment of the Austrian army), while his blue- jacketed companion might be a dragoon officer from eastern Europe.[7] While the unusualness of both the subject matter and composition might indicate a specific commission, Vogelmann used soldiers to personify the Four Elements[8] and gave two soldiers a prominent position in a figure group depicting a man and a woman drinking coffee at a table,[9] so it could be argued that soldiers were simply among the repertoire of types from which he drew.

The Kelsterbach factory focused production on figures and on small personal luxury objects, such as snuffboxes, scent bottles, and cane handles. Curiously, the factory appears to have made few, if any, dinner or dessert services; a factory inventory of 1769 lists no components for either type of service.[10] This absence of tablewares suggests that either the Landgrave was uninterested in this aspect of production or he furnished his table with silver or with porcelain acquired elsewhere. This focus on figures and small luxury objects to the exclusion of wares was highly unusual for an eighteenth- century manufactory, as dinner and dessert services were standard products for most concerns. The seeming lack of interest in tablewares at Kelsterbach points to the very personal nature of many of the aristocratic porcelain factories, most of which were established due either to the founder’s passion for porcelain or to a desire to elevate the status of one’s court through such patronage. As these enterprises were rarely profitable in the eighteenth century, they required substantial infusions of funds from the founding patron or his heirs in order to survive. Kelsterbach was almost entirely dependent on Landgrave Ludwig VIII’s financial support, which came from his private income,[11] and with his death in 1768, the factory was no longer able to continue.

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 Christ 2010.

2 Walcha 1981, p. 164.

3 Abraham 2010, p. 119, in which the author writes that “almost two-thirds of the figural production is attributed to the chief modeler Carl Friedrich Vogelmann.”

4 Christ 2011, p. 132.

5 See, for example, ibid., fig. 17.

6 Hofmann 1980, p. 286, under no. 113. A copy of the print is in the Museum (69.603).

7 Helmut Nickel, former Curator, Department of Arms and Armor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, notes in the curatorial files, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

8 Christ 2011, fig. 21.

9 Ibid., fig. 19.

10 Christ 2010.

11 Ibid.

All of these circumstances applied to the Kelsterbach factory, which had its roots quite commonly in the production of faience and which struggled financially from its inception.[1] It appears a faience factory was established in Königstädten in 1758 after receiving a charter that same year from Landgrave Ludwig VIII von Hessen- Darmstadt (1691–1768), in whose domain Königstädten was located. However, the factory moved to the nearby town of Kelsterbach later that year after a change of ownership. The factory’s faience production never became commercially viable, and in 1761 the Landgrave assumed ownership just as porcelain production became the factory’s sole focus.

It appears that the requisite technical knowledge at Kelsterbach was provided by Christian Daniel Busch (German, 1722–1790), who had been employed at Meissen both as a painter and as a developer of enamel colors. Busch’s career typifies the itinerant nature of many workers in ceramic factories in the eighteenth century, because he left Meissen to work at factories in Vienna, Munich, Künersberg, and Sèvres before arriving at Kelsterbach in 1761.[2] He served as director of the Kelsterbach factory until 1764, at which time he returned to Meissen for the remainder of his career.

The modeler Carl Vogelmann (German, active 1759–84), who had been previously employed at Ludwigsburg in the years 1759–60, was hired by Kelsterbach at the outset, and while other modelers worked at the factory—notably Jakob (German, active at Kelsterbach 1763–64) and Johann Carlstadt (German, at Kelsterbach by 1764)—the majority of the figures produced by the factory are attributed to Vogelmann’s hand,[3] and seventy- five plaster molds by him were listed in a 1769 inventory of the factory.[4] His figures are characterized by their unusual and expressive faces, prominent eyes, and a certain ungainly quality to their modeling. One of the most distinctive features of his figural groups is the elaborate architectural frames in which the figures are placed. Composed of robust, highly sculptural C- scrolls, these quintessentially Rococo stage sets have as much visual presence as the figures that inhabit them.[5]

This figure group depicting two soldiers displays all of Vogelmann’s stylistic traits, as well as his predilection for unconventional compositions. The two soldiers shake hands in front of a tent that covers a small table holding a bottle, two beakers, and a plate of bread. This scene is elevated on a stand composed of large, sinuous C-scrolls; two cannons and accompanying cannonballs rest on the base. The basic composition of the group may derive from a portrait of the Austrian military commander Gideon Ernst Freiherr von Laudon (1717–1790) by the printmaker Johann Esaias Nilson (German, 1721–1788).[6] Von Laudon rose to prominence during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) due to his military successes, and Nilson has included two soldiers in the fore-ground of the portrait in poses very similar to those in the Kelsterbach group. In both the print and the porcelain group it appears that a truce is being celebrated, although no specific event has been identified that might have been the impetus for the composition. The soldiers’ costumes do not immediately reveal their identities, although it has been suggested by Helmut Nickel that the soldier in the red jacket may be a Pandour (a member of the Croatian regiment of the Austrian army), while his blue- jacketed companion might be a dragoon officer from eastern Europe.[7] While the unusualness of both the subject matter and composition might indicate a specific commission, Vogelmann used soldiers to personify the Four Elements[8] and gave two soldiers a prominent position in a figure group depicting a man and a woman drinking coffee at a table,[9] so it could be argued that soldiers were simply among the repertoire of types from which he drew.

The Kelsterbach factory focused production on figures and on small personal luxury objects, such as snuffboxes, scent bottles, and cane handles. Curiously, the factory appears to have made few, if any, dinner or dessert services; a factory inventory of 1769 lists no components for either type of service.[10] This absence of tablewares suggests that either the Landgrave was uninterested in this aspect of production or he furnished his table with silver or with porcelain acquired elsewhere. This focus on figures and small luxury objects to the exclusion of wares was highly unusual for an eighteenth- century manufactory, as dinner and dessert services were standard products for most concerns. The seeming lack of interest in tablewares at Kelsterbach points to the very personal nature of many of the aristocratic porcelain factories, most of which were established due either to the founder’s passion for porcelain or to a desire to elevate the status of one’s court through such patronage. As these enterprises were rarely profitable in the eighteenth century, they required substantial infusions of funds from the founding patron or his heirs in order to survive. Kelsterbach was almost entirely dependent on Landgrave Ludwig VIII’s financial support, which came from his private income,[11] and with his death in 1768, the factory was no longer able to continue.

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 Christ 2010.

2 Walcha 1981, p. 164.

3 Abraham 2010, p. 119, in which the author writes that “almost two-thirds of the figural production is attributed to the chief modeler Carl Friedrich Vogelmann.”

4 Christ 2011, p. 132.

5 See, for example, ibid., fig. 17.

6 Hofmann 1980, p. 286, under no. 113. A copy of the print is in the Museum (69.603).

7 Helmut Nickel, former Curator, Department of Arms and Armor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, notes in the curatorial files, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

8 Christ 2011, fig. 21.

9 Ibid., fig. 19.

10 Christ 2010.

11 Ibid.

Artwork Details

- Title: Two soldiers shaking hands

- Manufactory: Kelsterbach Pottery and Porcelain Manufactory (German, 1758–ca. 1823)

- Modeler: Probably Carl Vogelmann (German, active Kelsterbach, 1764–66)

- Date: 1761–64

- Culture: German, Kelsterbach

- Medium: Hard-paste porcelain decorated in polychrome enamels, gold

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 7 3/16 × 5 9/16 × 3 5/8 in. (18.3 × 14.1 × 9.2 cm)

- Classification: Ceramics-Porcelain

- Credit Line: Gift of R. Thornton Wilson, in memory of Florence Ellsworth Wilson, 1950

- Object Number: 50.211.256

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.