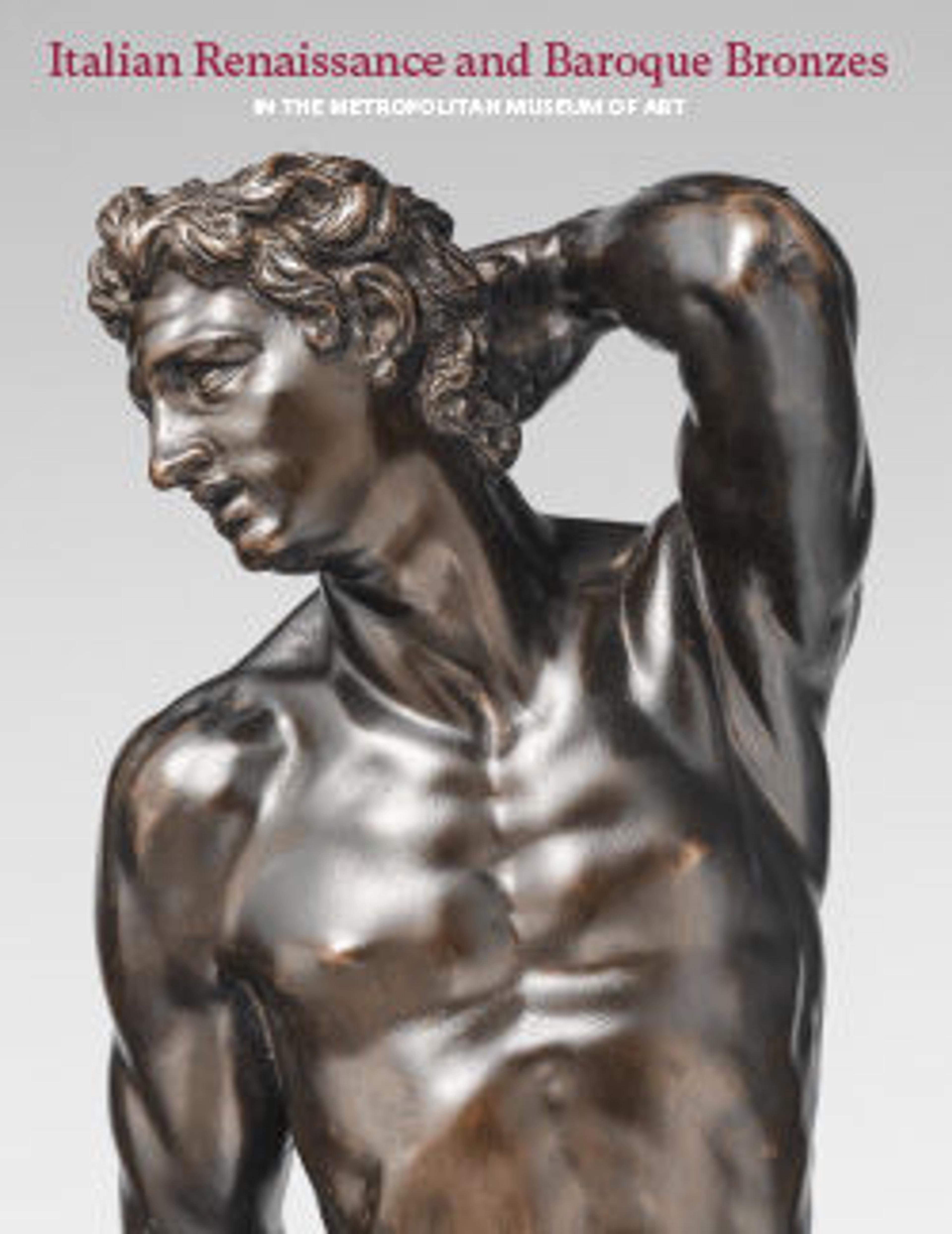

Saint Francis Xavier with an angel holding a crucifix

According to an 1817 guidebook, Francesco Bertos was a “valiant disciple” of the Venetian marble sculptor Giovanni Bonazza.[1] Francesco was conceivably related to one Girolamo Bertos who was engaged in carving marble altarpieces in Ravenna with Pietro Toschini about 1700. In 1708 or 1709, a letter from Ravenna reached Giovanni Battista Foggini in Florence, recommending that he receive Francesco and impart to him lessons in the trade of sculptor.[2] Thus we have two plausible poles to account for Bertos’s beginnings: on one hand, the rather slapdash manner of Bonazza and other marble specialists among the many teams of carvers working for the churches and villas of the Veneto; on the other, a certain zest for modeling works intended to be cast in bronze—an art that had all but died out in Venice and Padua by the time Bertos came along but that received new impetus generated by the theatrical Baroque configurations of Foggini and his peers in Florence. Bertos would eventually direct an atelier as busy as theirs but one that showed a significantly less dependable range of quality.

Charles Avery’s 2008 catalogue raisonné runs to 215 objects coming from Bertos. Within that oeuvre, the present saints stand out for their size and the sheer conviction of their robust modeling and casting.[3] They are his masterpieces, if the term can be said to apply in his case. Avery suspects a dating near 1722, the centennial year of the saints’ canonization,[4] and it is indeed tempting to date them to Bertos’s early maturity, when his talent must have been strongest.

The two saints were cofounders of the Order of the Society of Jesus, generally known as the Jesuits. The statuettes interrelate best when Ignatius Loyola is placed to Francis Xavier’s left, so that the infant angels enclose them parenthetically. Their types, with jerky movements and retroussé noses, are present in the majority of Bertos’s bronzes and marbles and constitute indelible proof of his authorship. Otherwise, the slowly unwinding compositions, although they could never be called Mannerist, hearken back to the long tradition of Venetian bronze statuary continued in the sixteenth century by masters such as Girolamo Campagna. The figures also compose most happily when placed at an angle to each other. We can hardly guess at the configuration of their chapel or altar, probably small but no doubt installed in a Jesuit setting of considerable Baroque panache. The two saints had firm connections to Venice, having both been ordained there in 1537, before Francis Xavier set forth on his missions in the East. The glorious Baroque church ensembles of the Gesuati and the Gesuiti in Venice come readily enough to mind, but neither can be pinpointed as the site of the altar in question.

Francis Xavier was born Francisco de Jaso y Azpilicueta in the castle of Javier in Navarre in 1506. He banded together with the older Ignatius Loyola, Pierre Favre, and four other students in Paris as early as 1534 to form what would become the Society of Jesus. He and Ignatius shared quarters on and off until his departure eastward. Francis was a zealous missionary, indefatigable until his death on an island off China in 1552. His ascetic, indeed gaunt features were widely circulated through countless images.[5] Bertos shows him in his short cloak, the mantellina, parted over a cross near his heart in allusion to his ecstatic unions with Christ. His putto brandishes a crucifix as if in playful imitation of the preacher. Its dead Christ, with shapes both stark and fluid, is an especially moving passage. Avery points out its similarity to those in three bronze groups by Bertos,[6] relatively abstract and probably later.

Ignatius Loyola, born Iñigo Oñaz López de Loyola in 1491 in the castle of Loyola in Basque Country, was, like Francis Xavier, a member of the nobility who renounced worldly pleasures to embrace the religious life. He penned his famous Spiritual Exercises in about 1521–22. A bull of Paul III approved the constitution of the Society of Jesus, and Ignatius was elected the order’s first superior general in 1541. It was he who coined the order’s motto, displayed on the open book reverently supported by the bronze putto: AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM (To the greater glory of God), to which is appended SOCIETATIS GIESV FVNDATO[R] (Founder of the Society of Jesus). Like Francis Xavier’s, Ignatius’s kindly, careworn, heart-shaped visage was familiar through a vast iconography.[7] A brilliant administrator, he deployed members of the Jesuit community on missions throughout the world, the order numbering at least a thousand by the time of his death in Rome in 1556.

The early Jesuits deliberately eschewed official vestments. We can almost feel the rough wool in which these saints are clad, reinforced by the vivid sweeps of chasing throughout their folds, particularly vibrant on their backs. The ruddy metal was seemingly never patinated except by oils, making for an uncommonly attractive, warm sheen. The Francis Xavier had lost its halo by 1979; the present one is a copy based on that of its pendant.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Moschini 1976, pp. 182, 253. See also Guerriero 2002.

2. C. Avery 2008, pp. 13, 21 n. 6.

3. The statuettes were cast indirectly with a plaster core. Radiography reveals evidence of extensive porosity and significant casting flaws throughout that were repaired with poured and pinned patches. A number of elements were cast onto the figures, including the putti, Ignatius Loyola’s left forearm and book, and additional sections of the arms and drapery. The putto’s cross and Saint Francis Xavier’s staff were joined mechanically. The surfaces were freely worked with a variety of tools, including chisels. L. Borsch/TR, January 10, 2010.

4. C. Avery 2008, p. 57.

5. Torres Olleta 2009.

6. C. Avery 2008, pls. 45–49, 250, 251, nos. 171–73.

7. König-Nordhoff 1982; O’Malley and Bailey 2003, esp. pp. 206–7.

Charles Avery’s 2008 catalogue raisonné runs to 215 objects coming from Bertos. Within that oeuvre, the present saints stand out for their size and the sheer conviction of their robust modeling and casting.[3] They are his masterpieces, if the term can be said to apply in his case. Avery suspects a dating near 1722, the centennial year of the saints’ canonization,[4] and it is indeed tempting to date them to Bertos’s early maturity, when his talent must have been strongest.

The two saints were cofounders of the Order of the Society of Jesus, generally known as the Jesuits. The statuettes interrelate best when Ignatius Loyola is placed to Francis Xavier’s left, so that the infant angels enclose them parenthetically. Their types, with jerky movements and retroussé noses, are present in the majority of Bertos’s bronzes and marbles and constitute indelible proof of his authorship. Otherwise, the slowly unwinding compositions, although they could never be called Mannerist, hearken back to the long tradition of Venetian bronze statuary continued in the sixteenth century by masters such as Girolamo Campagna. The figures also compose most happily when placed at an angle to each other. We can hardly guess at the configuration of their chapel or altar, probably small but no doubt installed in a Jesuit setting of considerable Baroque panache. The two saints had firm connections to Venice, having both been ordained there in 1537, before Francis Xavier set forth on his missions in the East. The glorious Baroque church ensembles of the Gesuati and the Gesuiti in Venice come readily enough to mind, but neither can be pinpointed as the site of the altar in question.

Francis Xavier was born Francisco de Jaso y Azpilicueta in the castle of Javier in Navarre in 1506. He banded together with the older Ignatius Loyola, Pierre Favre, and four other students in Paris as early as 1534 to form what would become the Society of Jesus. He and Ignatius shared quarters on and off until his departure eastward. Francis was a zealous missionary, indefatigable until his death on an island off China in 1552. His ascetic, indeed gaunt features were widely circulated through countless images.[5] Bertos shows him in his short cloak, the mantellina, parted over a cross near his heart in allusion to his ecstatic unions with Christ. His putto brandishes a crucifix as if in playful imitation of the preacher. Its dead Christ, with shapes both stark and fluid, is an especially moving passage. Avery points out its similarity to those in three bronze groups by Bertos,[6] relatively abstract and probably later.

Ignatius Loyola, born Iñigo Oñaz López de Loyola in 1491 in the castle of Loyola in Basque Country, was, like Francis Xavier, a member of the nobility who renounced worldly pleasures to embrace the religious life. He penned his famous Spiritual Exercises in about 1521–22. A bull of Paul III approved the constitution of the Society of Jesus, and Ignatius was elected the order’s first superior general in 1541. It was he who coined the order’s motto, displayed on the open book reverently supported by the bronze putto: AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM (To the greater glory of God), to which is appended SOCIETATIS GIESV FVNDATO[R] (Founder of the Society of Jesus). Like Francis Xavier’s, Ignatius’s kindly, careworn, heart-shaped visage was familiar through a vast iconography.[7] A brilliant administrator, he deployed members of the Jesuit community on missions throughout the world, the order numbering at least a thousand by the time of his death in Rome in 1556.

The early Jesuits deliberately eschewed official vestments. We can almost feel the rough wool in which these saints are clad, reinforced by the vivid sweeps of chasing throughout their folds, particularly vibrant on their backs. The ruddy metal was seemingly never patinated except by oils, making for an uncommonly attractive, warm sheen. The Francis Xavier had lost its halo by 1979; the present one is a copy based on that of its pendant.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Moschini 1976, pp. 182, 253. See also Guerriero 2002.

2. C. Avery 2008, pp. 13, 21 n. 6.

3. The statuettes were cast indirectly with a plaster core. Radiography reveals evidence of extensive porosity and significant casting flaws throughout that were repaired with poured and pinned patches. A number of elements were cast onto the figures, including the putti, Ignatius Loyola’s left forearm and book, and additional sections of the arms and drapery. The putto’s cross and Saint Francis Xavier’s staff were joined mechanically. The surfaces were freely worked with a variety of tools, including chisels. L. Borsch/TR, January 10, 2010.

4. C. Avery 2008, p. 57.

5. Torres Olleta 2009.

6. C. Avery 2008, pls. 45–49, 250, 251, nos. 171–73.

7. König-Nordhoff 1982; O’Malley and Bailey 2003, esp. pp. 206–7.

Artwork Details

- Title: Saint Francis Xavier with an angel holding a crucifix

- Maker: Francesco Bertos (Italian, 1678–1741)

- Date: ca. 1722

- Culture: Italian, Padua

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): H. 25 x W. 14 x D. 6 1/16 in., 29lb. (63.5 x 35.6 x 15.4 cm, 13.1543kg)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Purchase, Assunta Sommella Peluso, Ignazio Peluso, Ada Peluso and Romano I. Peluso Gift, 2010

- Object Number: 2010.114

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.