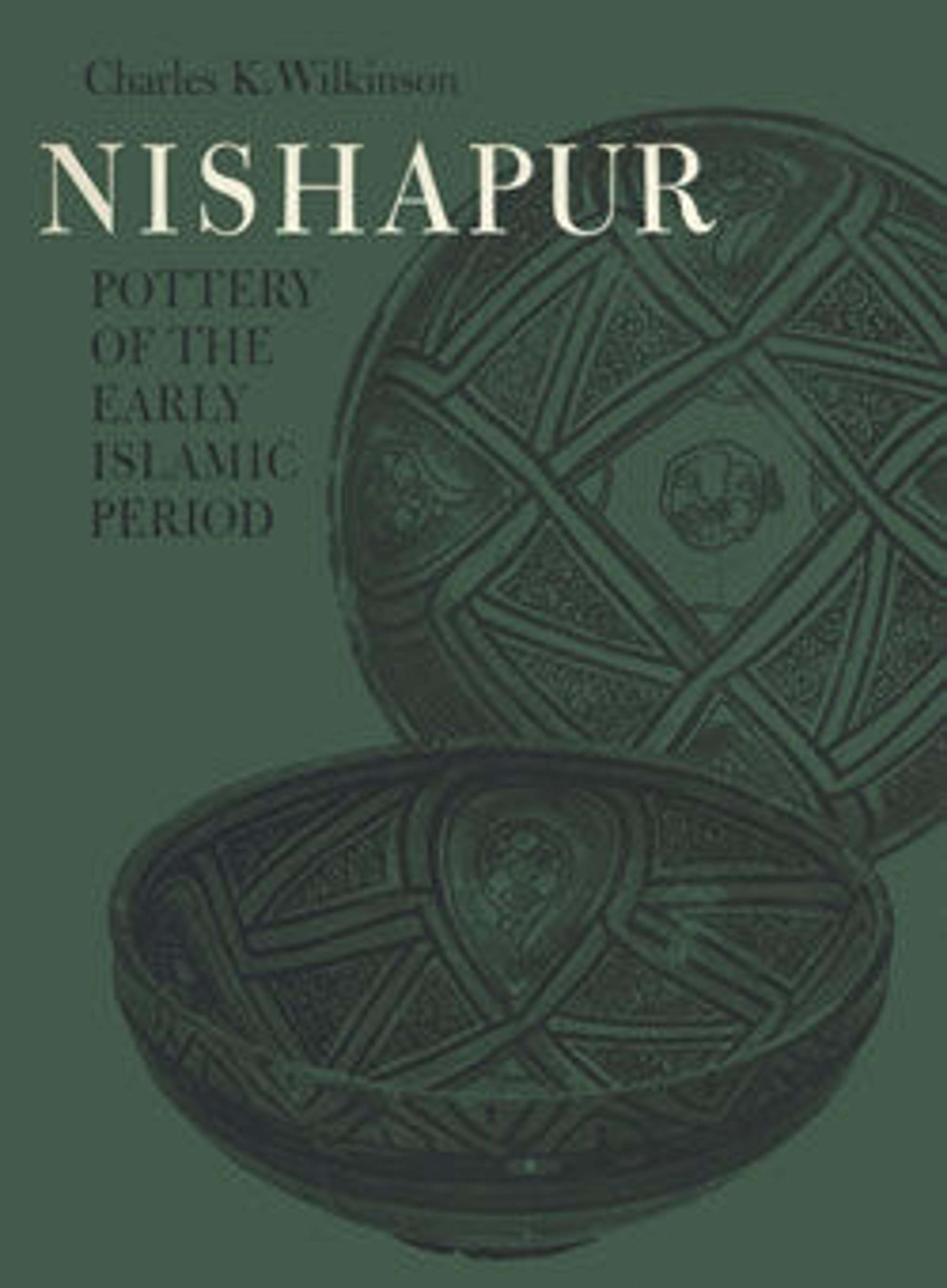

Ewer

This ceramic ewer was excavated at the site of Tepe Madrasa in Nishapur.

Nishapur was a vital city in the early and middle Islamic periods, located along one of the main trajectories that connected Iran and West Asia Islamic lands with Central Asia and China. These itineraries are often referred by the term ‘Silk routes’ but were in fact crucial to the movement of constellations of materials and objects, as well as people and ideas. The diverse population of Nishapur and its surroundings, from the better-researched elite groups of merchants, land-owning aristocracy, and literates, to the less-known artisans, farmers, miners, and servants, were instrumental in adapting global cultural trends to create their own distinctive visual languages. This is seen in the material remains of everyday life in medieval Nishapur – from pots and pans to lighting devices, inkwells, textiles and trimmings, jewelry, games and toys, talismanic devices, weapons, coins, and architectural fragments.

Nishapur lost its political prominence due to a series of earthquakes and invasions that peaked in the thirteenth century. Today, the medieval city is a vast archaeological area, while the relatively small modern city is situated to its north. Instead, Mashhad, a major pilgrimage site, emerged as a major prosperous metropolis in the region. Between 1935 and 1948, the "Persian Expedition" of the Metropolitan Museum of Art excavated at several sites at Nishapur under an agreement with the Iranian authorities. The recovered artifacts were divided in half between the two countries, resulting in over four thousand objects in the Met’s collection today.

As part of the larger "Persian Expedition" project at Nishapur, American archaeologists and hundreds of Iranian workers excavated a mound named Tepe Madrasa. There, they uncovered an architectural complex which they tentatively associated with a palace or governmental center because of the solidity of the built structures and the extent and variety of wall decorations (including carved and painted brickwork, glazed tiles, wall paintings, and carved and painted stuccoes). This, together with the ceramic and metal finds, aided in attributing the site to the ninth or tenth century onwards. A mosque, refurbished multiple times up to the late eleventh century, was also unearthed, yielding the remains of a monumental entrance with a large terracotta inscription bearing the titles of a sultan (39.40.58, .60–64). Several twelfth century tombstones were also unearthed, showing the shift in purpose of what was earlier a residential area.

Nishapur was a vital city in the early and middle Islamic periods, located along one of the main trajectories that connected Iran and West Asia Islamic lands with Central Asia and China. These itineraries are often referred by the term ‘Silk routes’ but were in fact crucial to the movement of constellations of materials and objects, as well as people and ideas. The diverse population of Nishapur and its surroundings, from the better-researched elite groups of merchants, land-owning aristocracy, and literates, to the less-known artisans, farmers, miners, and servants, were instrumental in adapting global cultural trends to create their own distinctive visual languages. This is seen in the material remains of everyday life in medieval Nishapur – from pots and pans to lighting devices, inkwells, textiles and trimmings, jewelry, games and toys, talismanic devices, weapons, coins, and architectural fragments.

Nishapur lost its political prominence due to a series of earthquakes and invasions that peaked in the thirteenth century. Today, the medieval city is a vast archaeological area, while the relatively small modern city is situated to its north. Instead, Mashhad, a major pilgrimage site, emerged as a major prosperous metropolis in the region. Between 1935 and 1948, the "Persian Expedition" of the Metropolitan Museum of Art excavated at several sites at Nishapur under an agreement with the Iranian authorities. The recovered artifacts were divided in half between the two countries, resulting in over four thousand objects in the Met’s collection today.

As part of the larger "Persian Expedition" project at Nishapur, American archaeologists and hundreds of Iranian workers excavated a mound named Tepe Madrasa. There, they uncovered an architectural complex which they tentatively associated with a palace or governmental center because of the solidity of the built structures and the extent and variety of wall decorations (including carved and painted brickwork, glazed tiles, wall paintings, and carved and painted stuccoes). This, together with the ceramic and metal finds, aided in attributing the site to the ninth or tenth century onwards. A mosque, refurbished multiple times up to the late eleventh century, was also unearthed, yielding the remains of a monumental entrance with a large terracotta inscription bearing the titles of a sultan (39.40.58, .60–64). Several twelfth century tombstones were also unearthed, showing the shift in purpose of what was earlier a residential area.

Artwork Details

- Title:Ewer

- Date:late 8th–9th century

- Geography:Excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Attributed to Iran, Nishapur

- Medium:Earthenware; buff slip, green glaze

- Dimensions:H. 8 11/16 in. (22 cm)

Diam. 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm) - Classification:Ceramics

- Credit Line:Rogers Fund, 1940

- Object Number:40.170.114

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.