Fig. 1. A view of one of the galleries in the exhibition Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World

"The exhibition's scale and scope are colossal; indeed, it even contains something of a colossus, a ten-foot-high marble image of Athena . . ."—The New Yorker

«We are enthralled by gigantic statues. The ancient Greeks called them kolossoi, a word first used by Herodotus to describe the massive stone statues of Pharaonic Egypt. Two famous colossal statues of Herodotus's time were Pheidias's awe-inspiring, gold-and-ivory cult statues of Athena Parthenos on the Acropolis of Athens (dedicated in 438 B.C.) and Zeus Olympios at Olympia, which was completed around 430 B.C. and was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.»

One can get an idea of both these lost works in the exhibition Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World, on view through July 17, which includes not one but four colossal statues—that is, at least twice life-size—all created during the second century B.C. The towering presence of the marble statue of Athena Parthenos, newly restored for the exhibition, greets visitors upon entering the third gallery (fig. 1). At almost 12 feet high (3.51 meters, including the base), it is a scaled-down, free adaptation of Pheidias's Athena Parthenos, which stood inside the Parthenon and measured approximately 40 feet tall.

The statue was discovered behind the north stoa of the Sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros (Athena of the City and Bearer of Victory), Pergamon's patron deity, which stood at the center of the citadel. This is where Pergamon's famous library was located, adorned with, in addition to the Athena, statues of illustrious literary figures of the past such as Homer and Herodotus. The back of the Pergamene statue is cursorily carved and only one block of its base survives. It preserves part of the relief that decorated the base of Pheidias's statue and illustrated the birth of Pandora, the creation myth of the first woman on earth, all endowed by the gods as her name suggests. The Attalid kings admired Classical painting and sculpture, and this impressive Athena is the best-known example of Pergamene Classicism.

Located in the same gallery, the emblematic marble bust of a young man (fig. 1), despite its fragmentary state, is among the finest surviving sculptures from Pergamon. In addition to the sensual facial features, strong bone structure, and long, curly hair, the figure is imbued by a dramatic intensity expressed by the turn of the head and the slightly open mouth. Originally the bust was set in a roundel almost four feet in diameter, one of many roundels adorning the main hall of the Gymnasium of Pergamon. It may represent a youthful god such as Helios (Sun) or even Alexander the Great, and belongs to a type of sculpture known as tondo, or shield-framed image (imago clipeata), which was widely employed in Roman and, later, European portraiture.

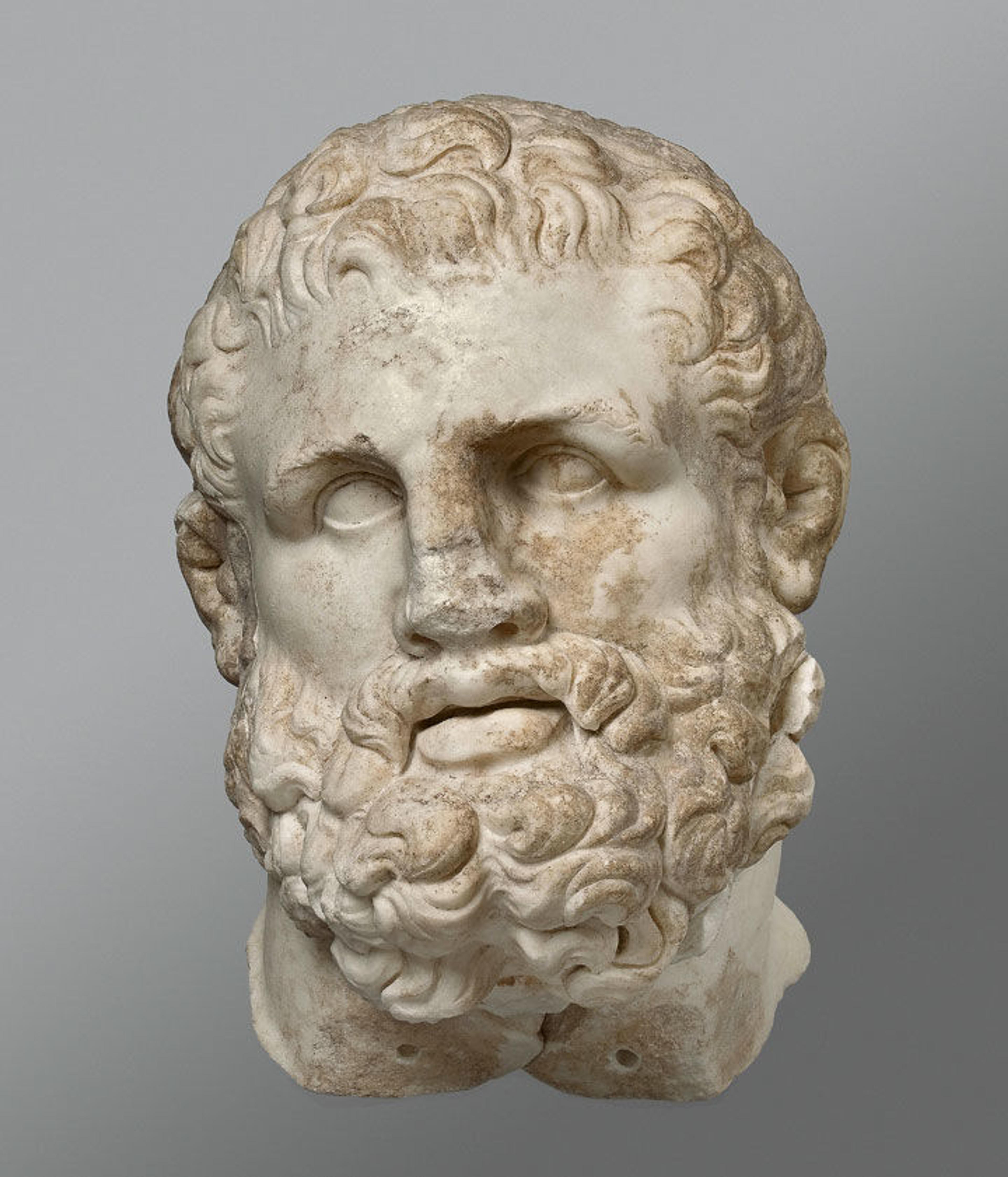

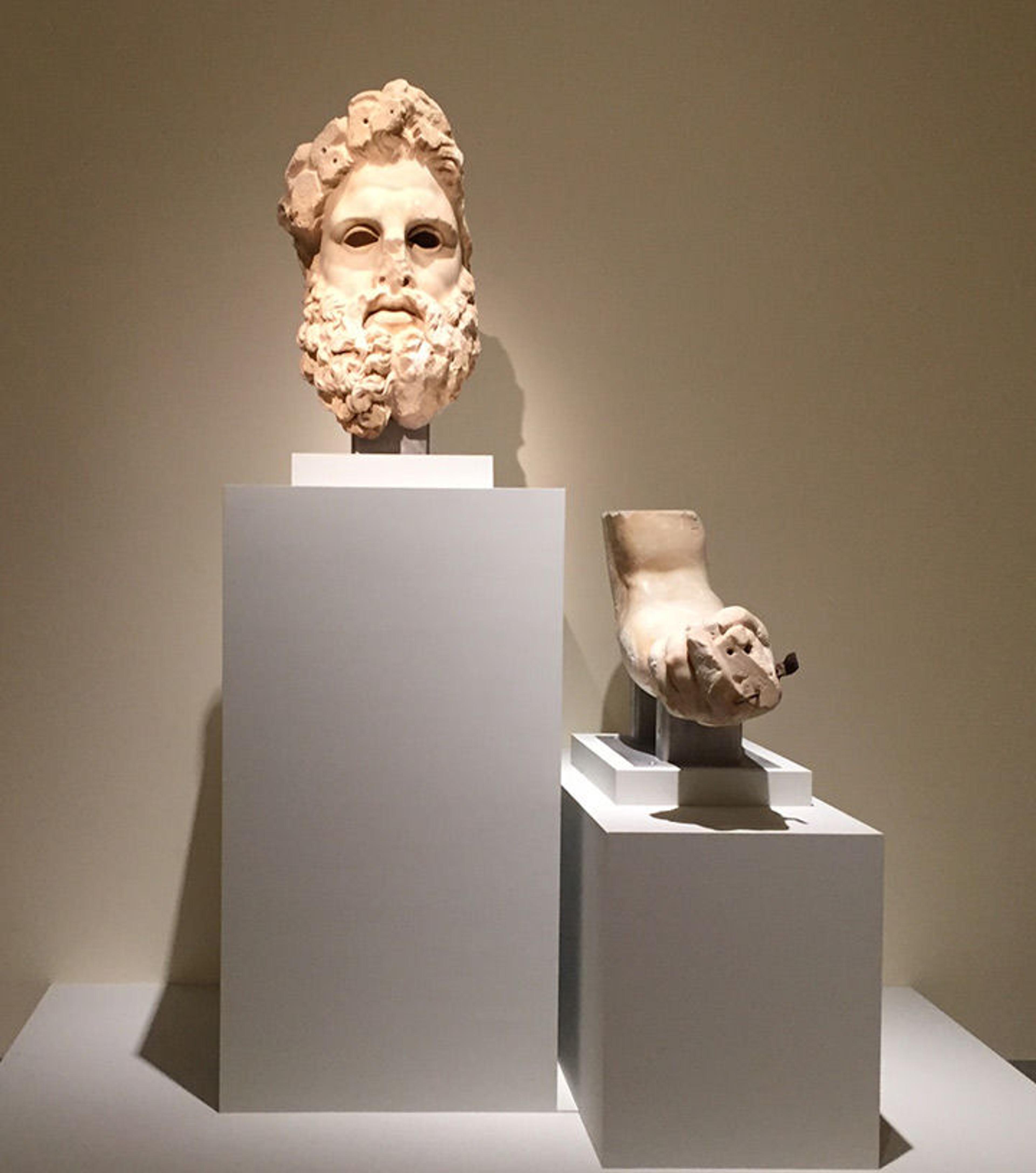

Another work from Pergamon's Gymnasium is the double-life-sized marble head of Herakles (fig. 2), which once belonged to a colossal seated statue of Herakles set up as a dedication to the hero next to portrait statues of the Attalid kings in military dress. His cauliflower ears and swollen nose, known from representations of boxers and other athletes, allude to Herakles's legendary strength and athleticism, while the figure's deeply set eyes, open mouth, and upward gaze are signature stylistic traits of the Hellenistic baroque. The presence of Herakles in a gymnasium was quite appropriate, but the hero had special ties to the Attalids, who were linked to Herakles and Zeus through Telephos, their legendary founder and son of Herakles.

Fig. 2. Colossal head of Herakles, 1st half of the 2nd century B.C. Greek, Hellenistic period. Marble; H. 19 1/4 in. (49 cm). Discovered at Pergamon, in a late wall in Room H of the gymnasium, 1906. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Sk 1675)

Beyond Pergamon, a revival of the Pheidian style is evident in a number of colossal statues of gods made by sculptors active in Athens and the Peloponnese during the second century B.C. Among them is the fragmentary acrolithic statue of Zeus from Aigeira, a small town in northwestern Peloponnese (fig. 3). The enormous head and left arm (about three times larger than life-size) have been associated with a cult statue of Zeus, the work of an Athenian sculptor named Eukleides, which the traveler Pausanias saw in one of the city's sanctuaries in the second century A.D. Combining Classical and baroque grandeur, the 35-inch-tall head showcases the eclectic style of the period. The inlaid eyes, now missing, would have intensified the god's daunting appearance. Zeus was represented as the crowned king of the gods, seated on a high-backed throne and holding a scepter and a winged image of Nike (Victory), very much like Pheidias's famed gold-and-ivory statue at Olympia.

Fig. 3. A view of the marble head and arm of a colossal statue of Zeus in the galleries. Greek, Hellenistic period, 150–100 B.C. Marble; head, H. 34 1/4 in. (87 cm); arm, L. 35 7/8 in. (91 cm). Found in Aigeira, Peloponnesos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens (3377 [head], 3481 [arm]). Photo by the author

Part of the same list of ancient wonders, the Colossus of Rhodes was the largest of all statues erected in antiquity (fig. 4). Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer of the first century A.D., wrote that among the colossal statues known to his day:

By far the most worthy of our admiration, is the colossal statue of the Sun, which stood formerly at Rhodes, and was the work of Chares the Lindian, a pupil of Lysippus; no less than seventy cubits in height [105 feet]. This statue fifty-six years after it was erected, was thrown down by an earthquake [ca. 226 B.C.]; but even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues… (Natural History 34.41)

Left: Fig. 4. Martin van Heemskerck. Colossus of Rhodes, 1572. Hand-colored engraving. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The bronze statue, which took about 12 years to complete, was admired not only for its enormous size but also for the technical mastery of its manufacture. Recent discoveries of bronze-casting pits and foundries on the island of Rhodes attest to an advanced metalworking technology. The statue represented the sun god Helios, nude and crowned with a sun-rayed diadem, and was perhaps an offering of thanks to the patron deity of the city-state of Rhodes. It was financed by the money raised from the sale of the abandoned siege engines used in the long-protracted but ultimately unsuccessful siege of Rhodes in 305/4 B.C. by the Macedonian king Demetrius I Poliorketes, a portrait of whom is displayed in the first gallery of the exhibition.

Both the exact location and pose of the colossus remain unknown. The statue probably stood near the military harbor of the city, gleaming in the sunlight and visible to the approaching ships in the sea. The image of the statue straddling over the entrance to the harbor, however, is part of a legend originating in the late 14th century A.D. and much embellished by Renaissance artists of the 16th century.

Liberty Enlightening the World, New York City's iconic landmark known as the Statue of Liberty, is a modern-day colossus that echoes the staging of the Rhodian sculpture but surpasses it in magnitude (fig. 6). Erected on a pedestal at Liberty Island (then Bedloe's Island) in Upper New York Bay overlooking the city's port, the monument stands as tall as a 22-story building—measuring just over 305 feet from the ground to the tip of the flame. A gift to the United States from France, the copper statue (151 feet/46 meters) was designed by the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Baltholdi and built by Gustave Eiffel. At the time of its dedication on October 28, 1886, it was the tallest statue in the world—a title now held by the Spring Temple Buddha, a 420-feet-high gilded-copper representation of Buddha Vairocana in China's Henan Province.

Fig. 5. A view of the Statue of Liberty and Jersey City. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Similar to the Colossus of Rhodes, the draped female figure of Liberty wears a radiant crown. Raising a torch with her right hand, she holds a tabula ansata, or tablet with handles, inscribed with the date of the American Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776) in Latin numerals, and a broken chain lies at her feet. Borrowing elements from iconography of Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom, the statue symbolizes the ideas of liberty and the abolition of slavery. As a personification of an abstract concept closely associated with an urban landscape, the Statue of Liberty preserves yet another link to the artistic legacy of the Hellenistic age: the statues of personifications and allegories that gradually became associated with the identity and fortune of cities.