Lord Kingsborough. The Antiquities of Mexico. London: Printed by James Moyse, 1831–1848. All images taken from two copies of the book held in Watson Library's collection.

«The story about a book's production can, on occasion, be wilder and more entertaining than the story the book contains. The Antiquities of Mexico, assembled from 1831 to 1848, is perhaps one such book. It is a compendium of reproductions of Mesoamerican literature, but the story of its creation plays out across French pirate ships, the great libraries of Europe, and the squalid cell of a 19th-century Irish prison.»

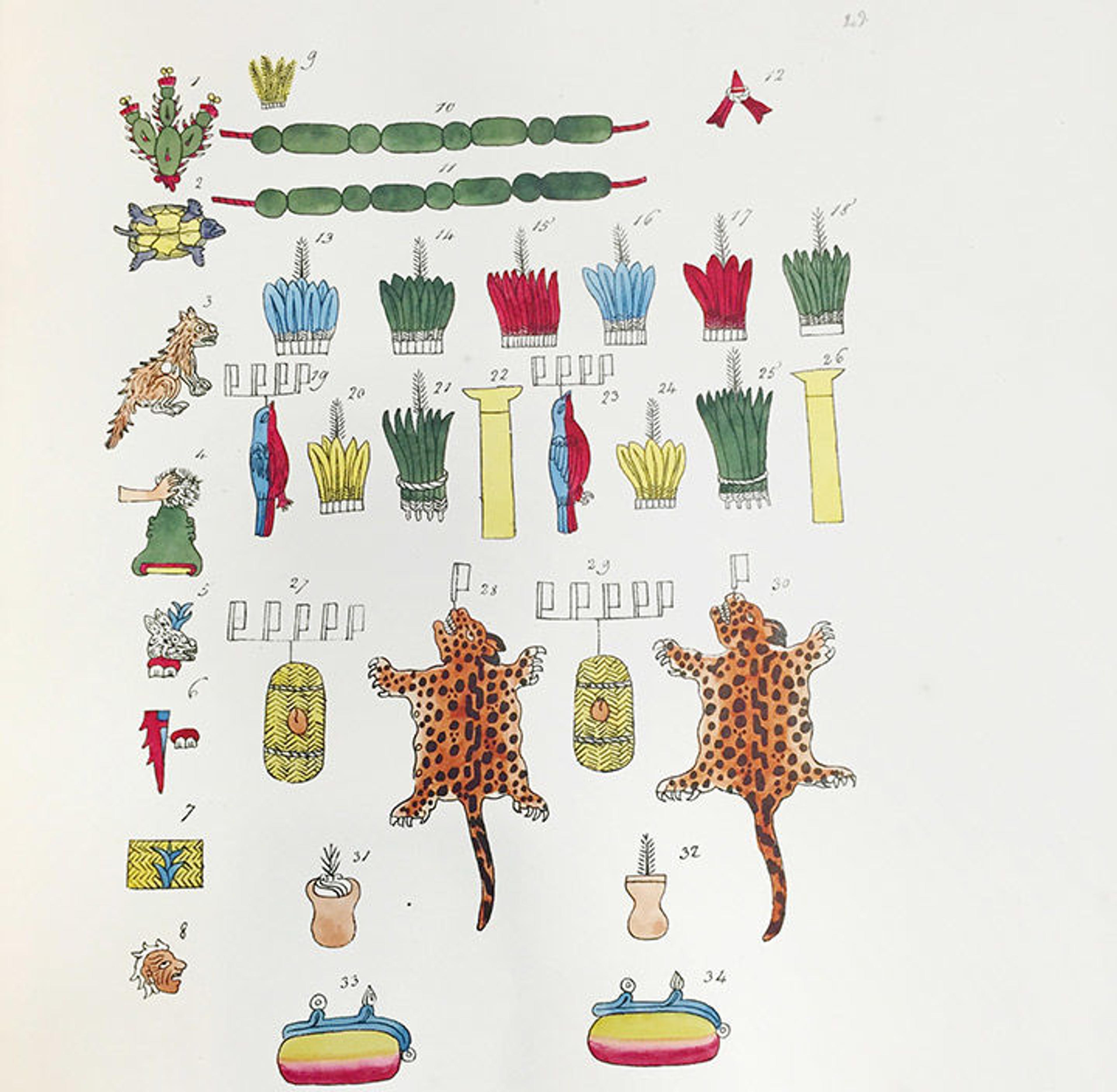

The book's fate is tied closely to that of Edward King, Viscount Kingsborough—a wealthy Irishman who was studying at Oxford University when he stumbled across The Codex Mendoza. This document, a 16th-century Aztec codex valued for its depiction of the Spanish conquest through Aztec pictograms, was created in Mexico and then sent to Spain by the conquistadors. En route, it was stolen by French pirates, sold off, changed hands several times, and finally ended up in the Bodleian Library in 1659, where it sat languishing in obscurity for almost 200 years until Kingsborough rediscovered it.

While working with the Codex Mendoza, Kingsborough became obsessed with Central American manuscripts and artifacts, and decided to devote the rest of his life to their study. In 19th-century Europe there was an abundance of original Mesoamerican documents deposited throughout the great libraries of Europe, but, unlike Watson Library, these libraries didn't have interlibrary loan or Digital Collections. Scholars wanting to study these documents had to travel a great distance, at great expense, to view them. Kingsborough recognized this problem and came up with a solution: he decided to create a facsimile of all the important Mesoamerican documents that existed in Europe, bind them up into one monumental work, and deposit a copy of that work at each major library. His beloved Codex Mendoza would be the first facsimile in the first volume.

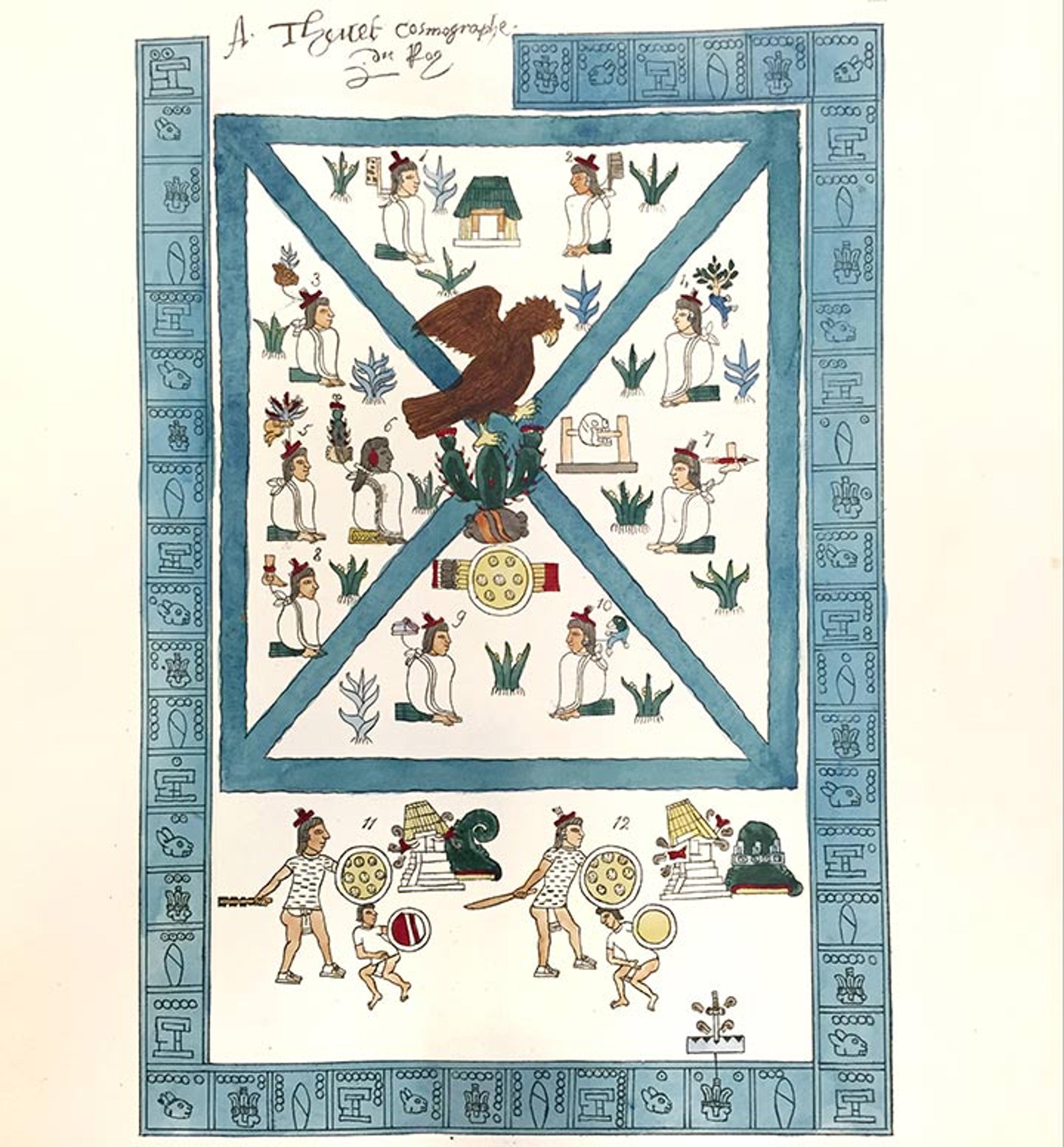

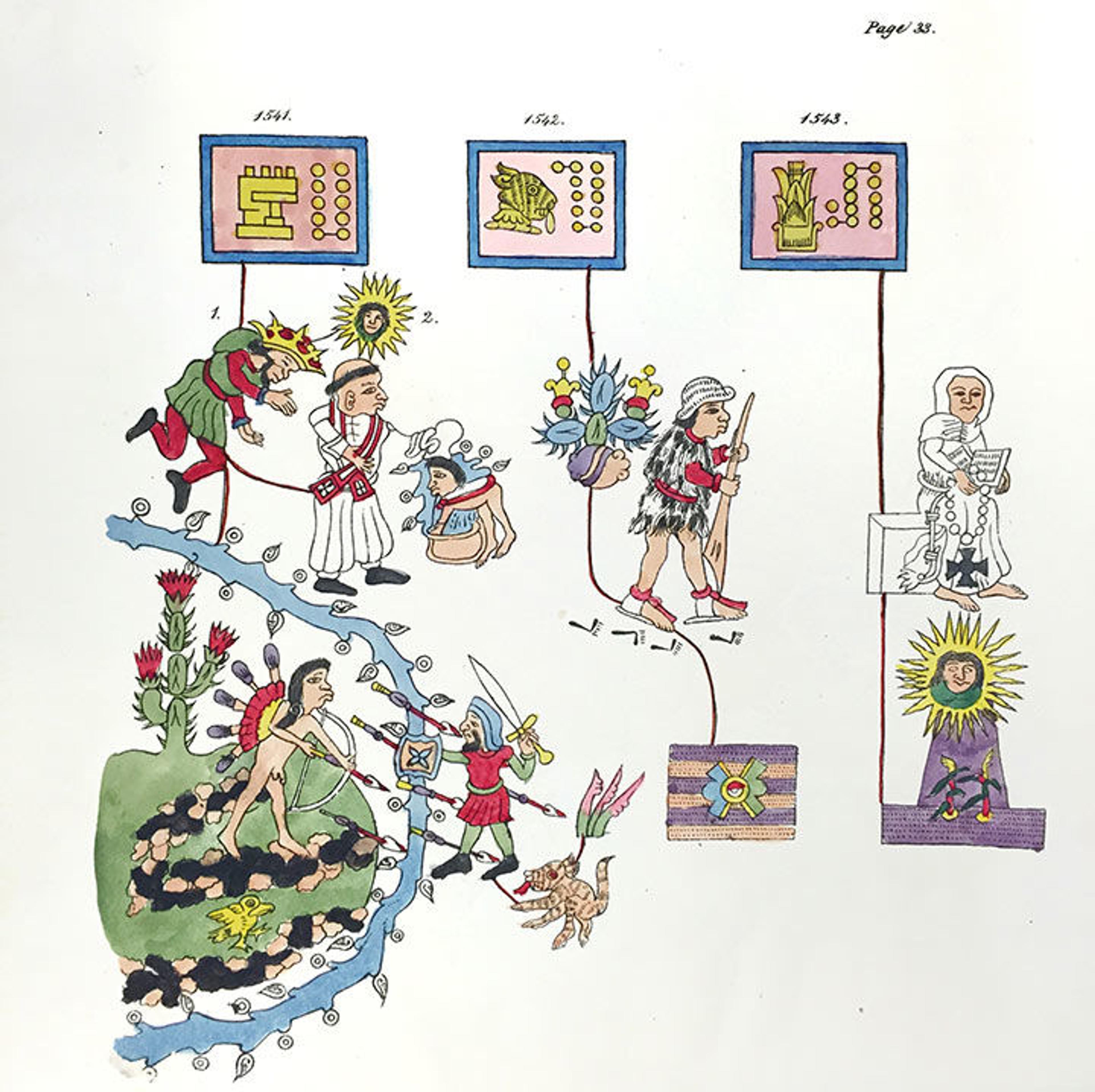

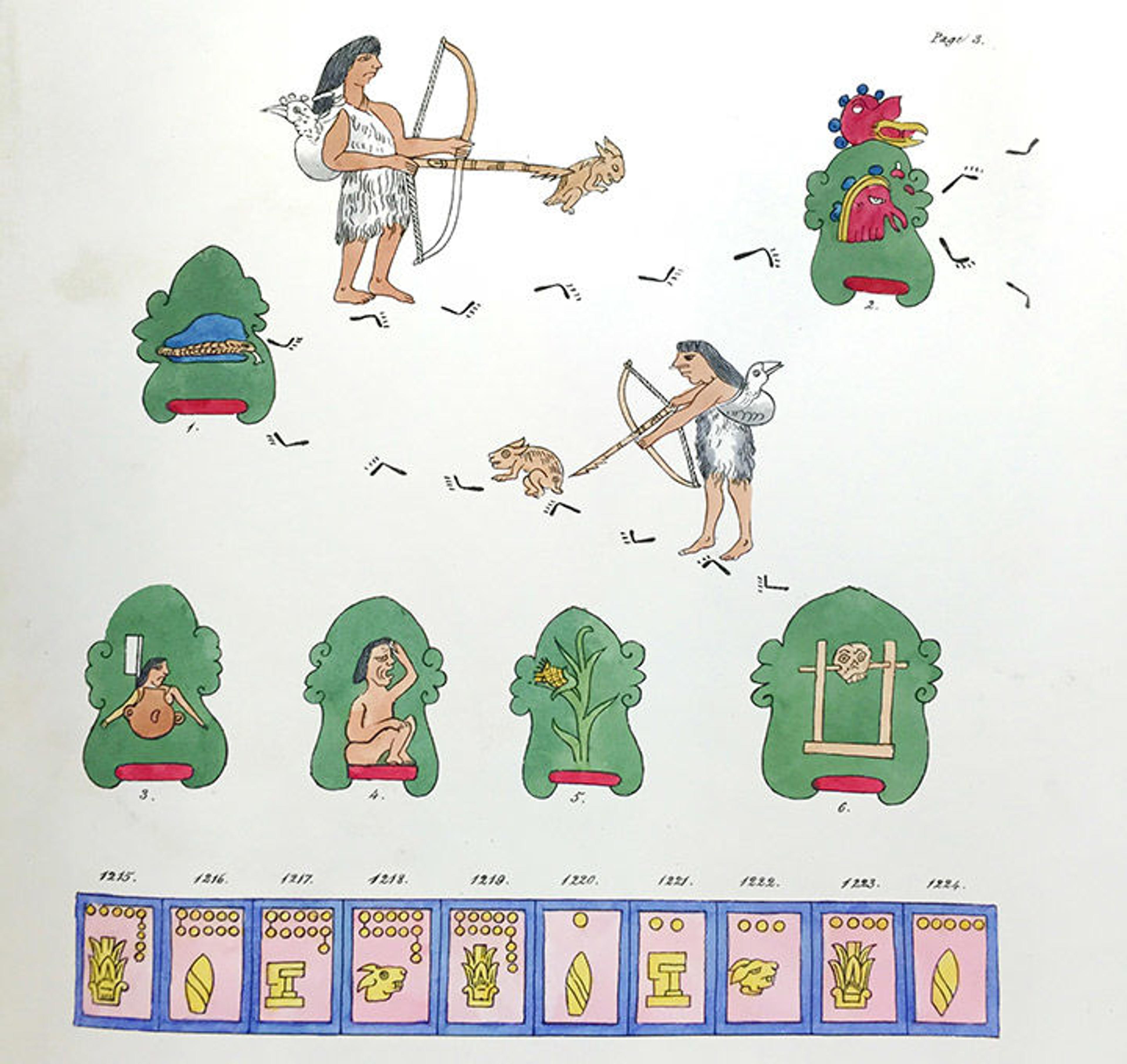

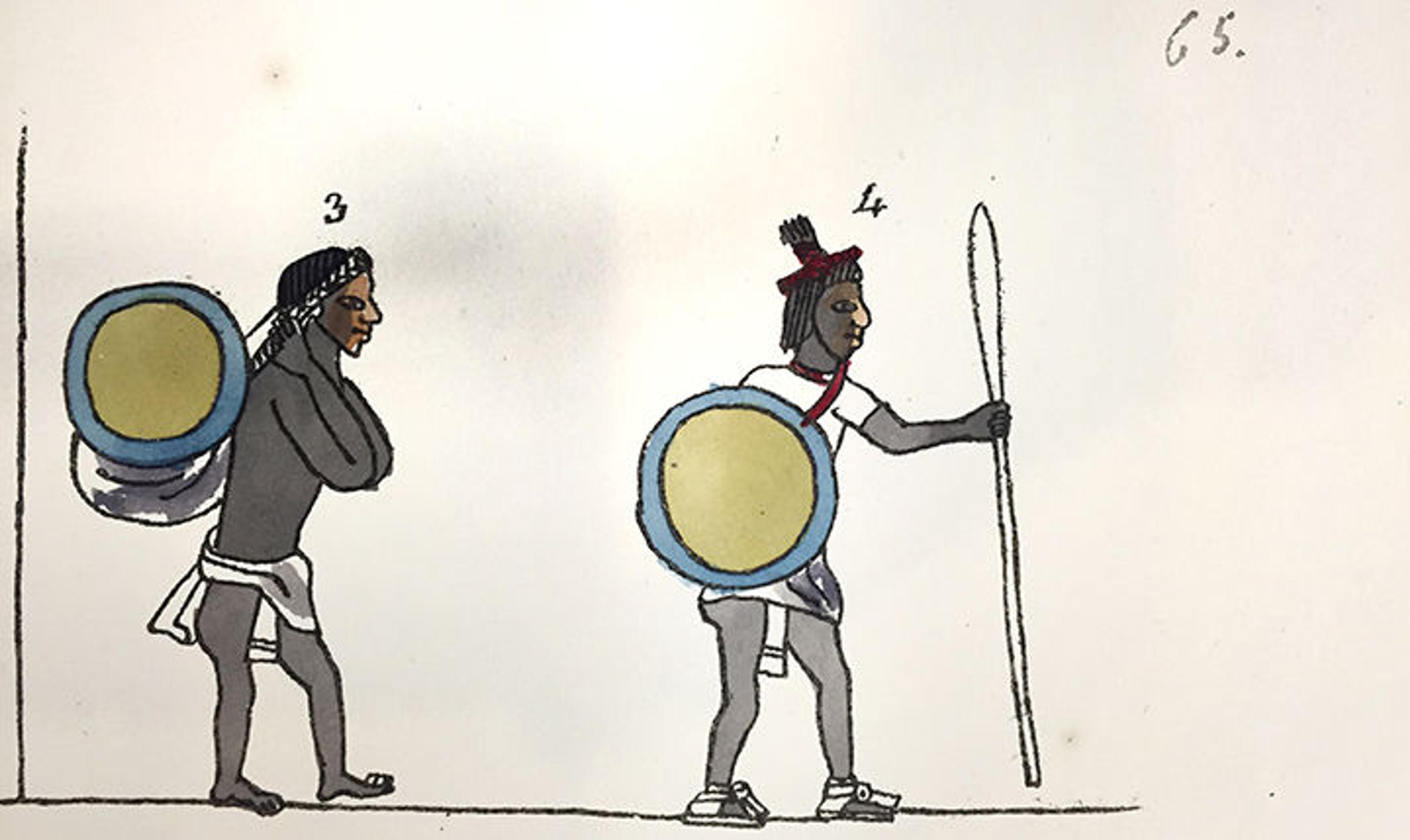

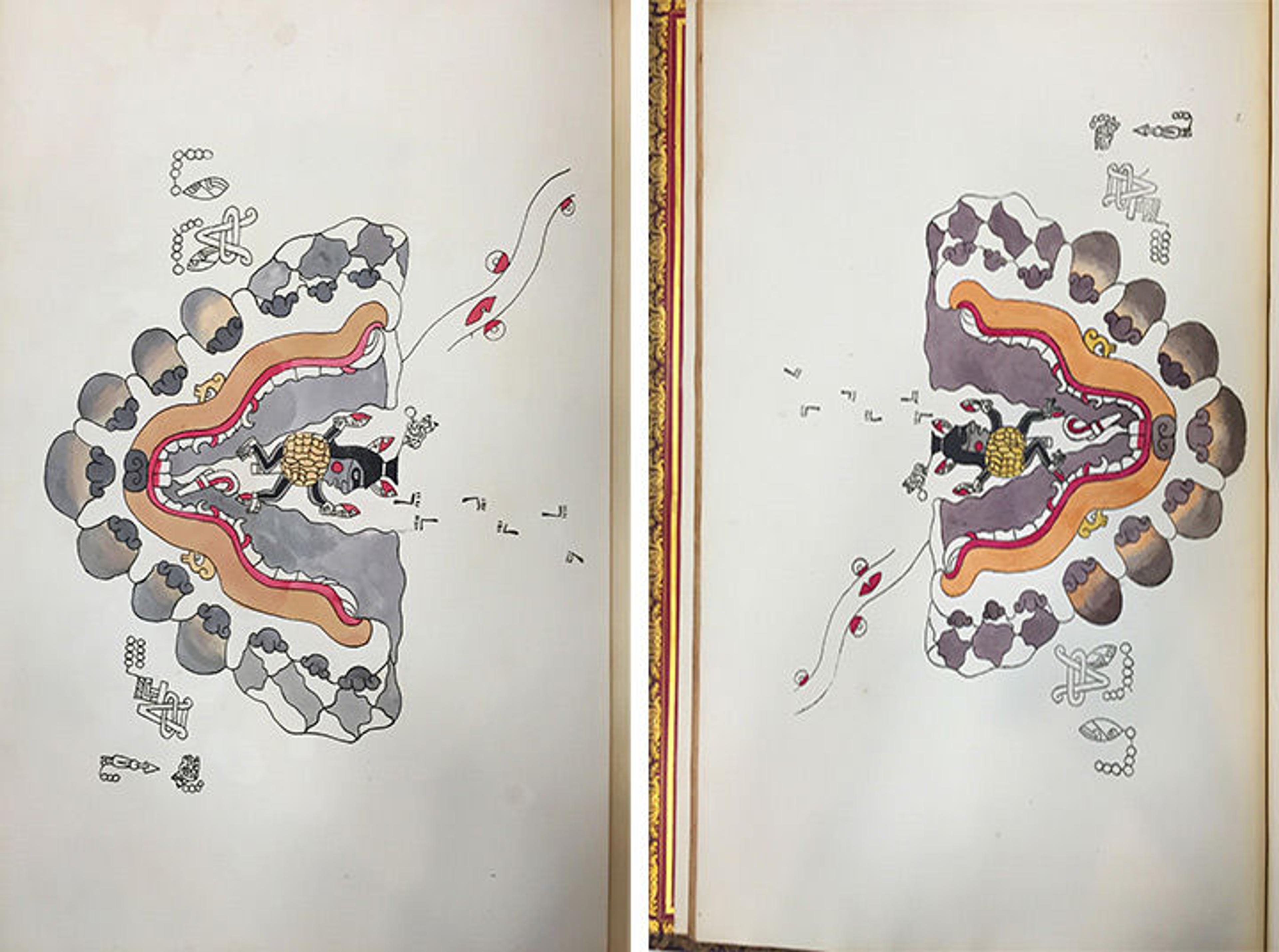

To complete this enormous undertaking, Kingsborough hired an Italian painter and engraver, Augustine "Angostino" Aglio. Aglio traveled to the royal libraries of Paris, Berlin, Dresden, the Imperial Library of Vienna, the Vatican, Rome, Bologna, and Oxford. It took Aglio somewhere between six and ten years to travel to all the libraries and make drawings from the originals. Aglio used translucent paper to make tracings in a one-to-one ratio, and then transferred the drawings to lithographic stones upon his return. The resulting prints, in black and white, were beautifully done, and many of the copies were then colored in by hand. Even though the coloring was all done or overseen by Aglio, the hand coloring resulted in variances of shade and color. Viewing the same illustration side by side (we have two separate copies in Watson) illustrates some of the variances (note the color of the shield as well as the shoes and head scarf on the figures below).

In addition to differing colors, one of Watson's copies of volume one has another variance: one of the illustrations was bound backwards in the book. This work would have been sold unbound in loose sheets, and then the purchaser would take the sheets and have them bound to their own specification. In this instance, the bookbinder accidentally bound one of the pages facing the wrong direction.

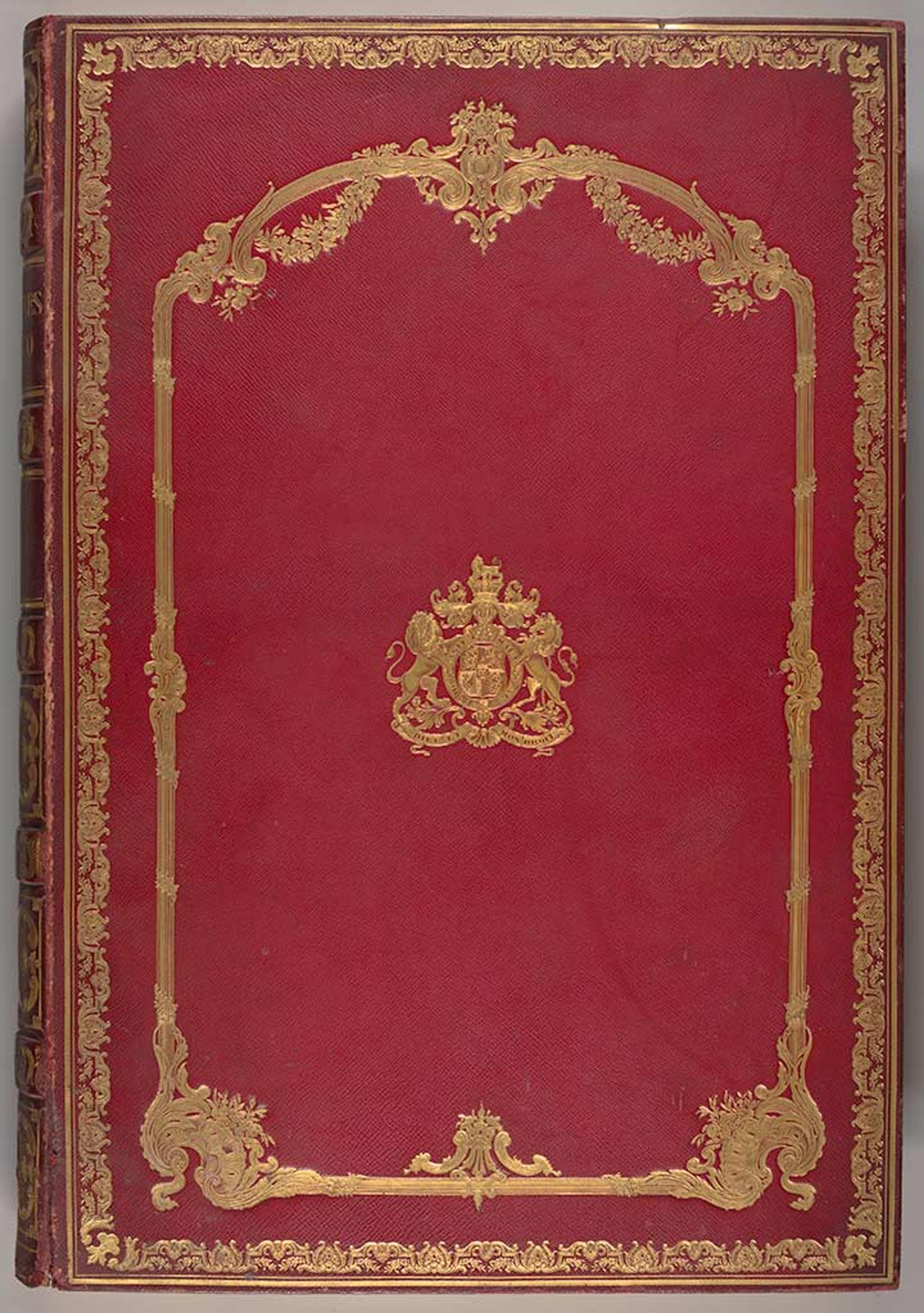

The finished book was an extremely lavish publication. While it is a scholarly work meant to be both accurate and faithful in its depiction of the codices, Kingsborough wanted it to be breathtaking in its splendor. He had staked his reputation on this publication and wanted it to be a work of art. The book is an elephant folio, roughly two feet tall; the illustrations (over 1,000 plates) are hand colored; the paper is very high quality, and the edges are gilt. One of Watson's copies is bound with an armorial binding, an expensive decorative choice, and a sign of how highly the owner valued the book.

Not surprisingly, the cost of paper, printing, and hand-colored illustrations really added up. On top of the cost of the book's production, Kingsborough had been sponsoring Aglio's travels through Europe for a long time. So in 1837 Kingsborough found himself imprisoned in Dublin for debts he owed to a paper manufacturer. The exorbitant cost of The Antiquities of Mexico had landed him in debtor's prison for the third time. Unfortunately, Kingsborough didn't last long after that: he contracted typhus and died a few days after being arrested. In an incredibly cruel twist of fate, his father died just a few short months later. Had Kingsborough outlived his father, he stood to inherit an annual estate of 40,000 pounds.

At the time of Kingsborough's death, seven volumes of The Antiquities of Mexico had been published. The printer, James Moyse, printed the last two posthumously, based on Kingsborough's notes. For the 10th volume, sadly, Kingsborough left only 60 pages of notes, so the great compendium remains unfinished.

The Robert Goldwater Library has two sets of The Antiquities of Mexico, and they can be paged and viewed in Watson Library. Despite the heavy toll it took on Kingsborough, he left behind an invaluable resource and an absolutely gorgeous book.