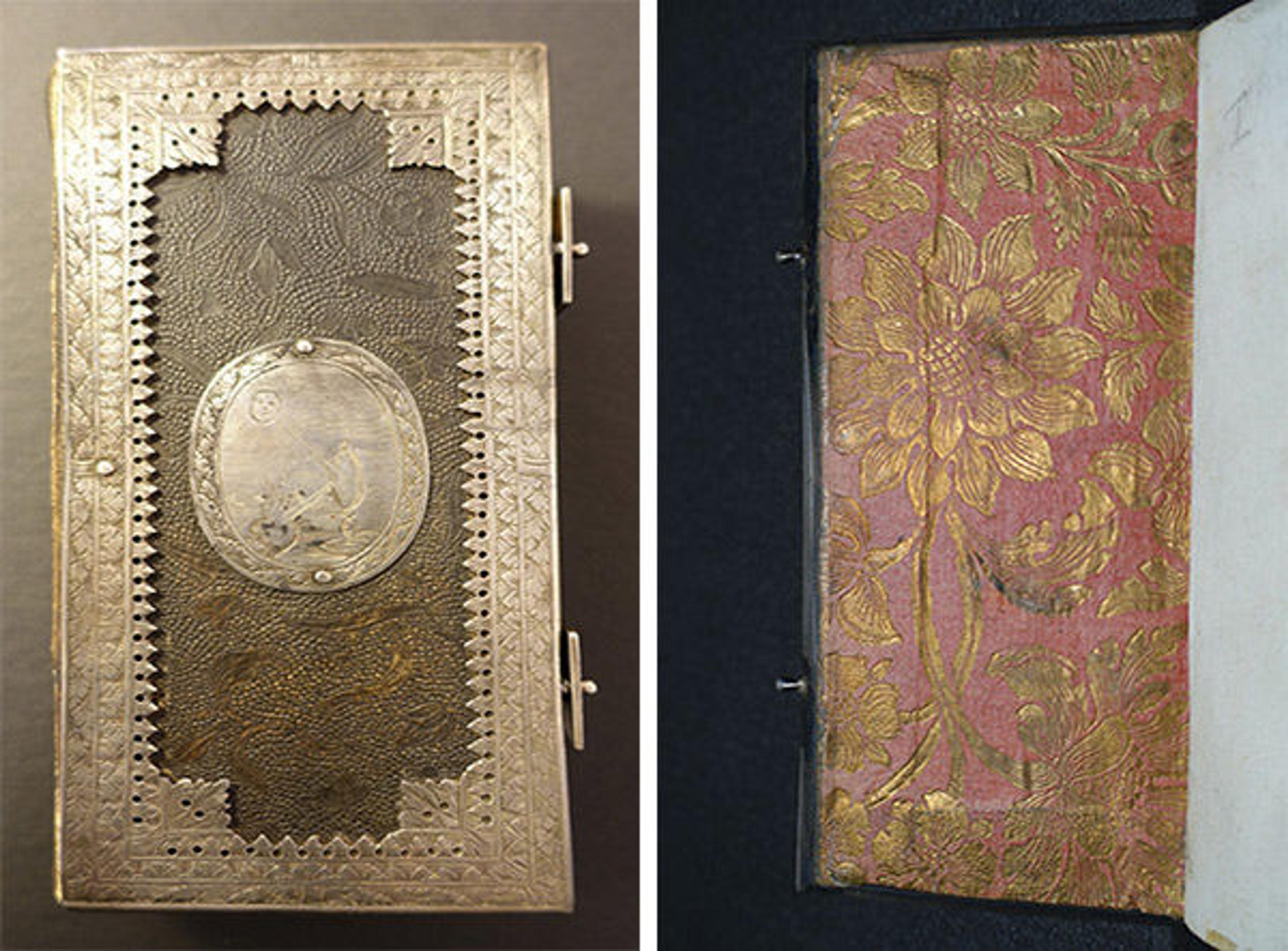

Arndt, Johann, Johann Arndts, Dess gottseeligen und hocherleuchteten lehrers Paradiess-gärtlein, welches voller christlichen tugend-gebete erfüllet. Deme zu ende beygefüget mehrere buss- und communion-gebete. Ulm: Druckts und verlegts Christian Ulrich Wagner, 1620

«Sometimes—and, in fact, frequently here in Watson—we do judge a book by its cover (or its endpapers). From the gold-tooled fine bindings of the Renaissance to nineteenth-century mass-produced publishers' bindings, the book as an object of beauty has always been important to collectors. While there are many techniques used to create decorated paper, four are represented here—paste, marbling, block printing, and Dutch gilt—in items from Watson Library's special collections.»

Left: Elwert, Anselm, Kleines Künstlerlexikon oder raisonnirendes Verzeichniß der vornehmsten Maler und Kupferstecher. Giesen: Krieger, 1785. Right: Krause, Susanne, and Claire Bolton, Paste paper = Kleisterpapier. Marcham: Alembic Press, 2002

The eighteenth-century German book pictured above reflects the common use of paste-paper covers at this time. Paste paper, which was produced starting in the late sixteenth century, was made from both vegetable dyes and inorganic pigments mixed with paste, and an endless variety of patterns could be achieved by manipulating the wet paste. Unlike other types of paper which involved extensive equipment and were made only by skilled craftsmen, paste paper could be made in the binding workshop, and the patterns that resulted represent an amazing range of detail and quality. The paper shown here was likely created by pressing two wet-pasted sheets together and pulling them apart, then making diagonal brushstrokes on the stippled background.

The modern samples above show some of the effects possible with paste paper. At the top, brushed paste paper and pulled paste paper are shown. Within pulled paper, many varieties can be obtained by pulling vertically or horizontally, at different stages of paste wetness, or by manipulating the papers before pulling them apart. The samples on the bottom half of the page show the impact of using different starches mixed with pigment on the final result. Although the same paper, pigment, and brush pattern are used throughout, the potato starch shown on the left lends a softer, cloudier appearance to the brushstrokes.

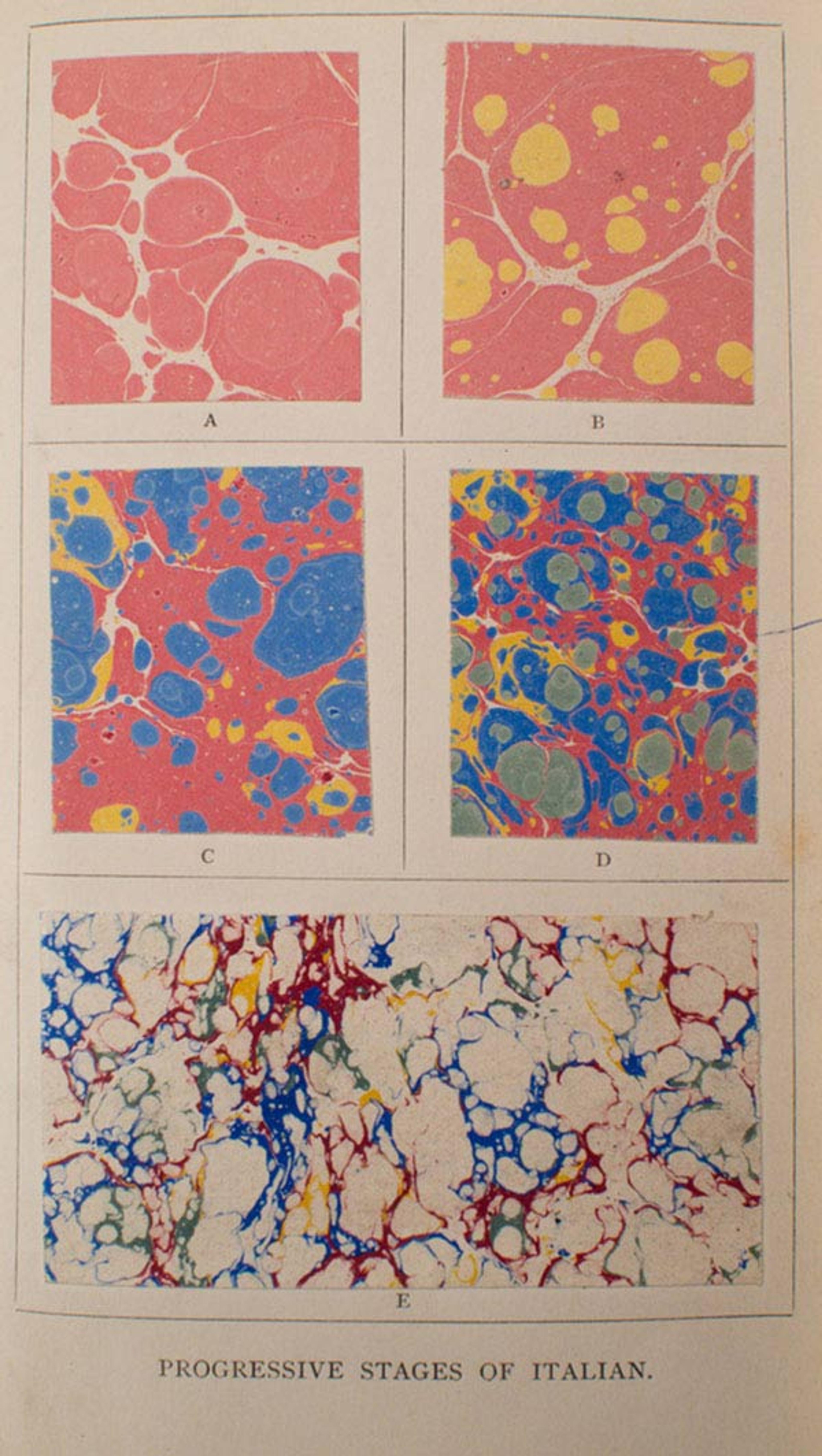

Woolnough, C. W., The Whole Art of Marbling as Applied to Paper, Bookedges, etc. London: George Bell and Sons, 1881

Marbled paper arrived in Europe in the seventeenth century (though earlier Eastern forms of marbling had already been in use for several hundred years, which you may remember from this earlier post on suminagashi), and is perhaps the most familiar of the decorated papers used in bindings. These papers were used for both endpapers and covers, and were—and continue to be—made in an endless variety of patterns. All marbled papers are made by suspending paint on the surface of a solution and laying paper down to take up the medium, and the patterns can be divided into combed and uncombed depending on whether the paint is manipulated into a regular pattern before laying the paper.

The page from The Whole Art of Marbling above shows marbling at each stage of the process, which illustrates the nature of the inks used and how they respond to added colors. The addition of the white at the end causes the previous pigments to gather tightly, resulting in the fine-veined pattern common in uncombed Italian papers.

Driuzzo, Francesco, Pinelli, Lucrezia Tiepoli, Antonio Nani, Giovanni De Pian, Francesco Bartolozzi, and Pietro Moro, Le Gemme per le Nozze Tiepolo-Nani. Venezia: Nella Tipografia Pinelli, 1812

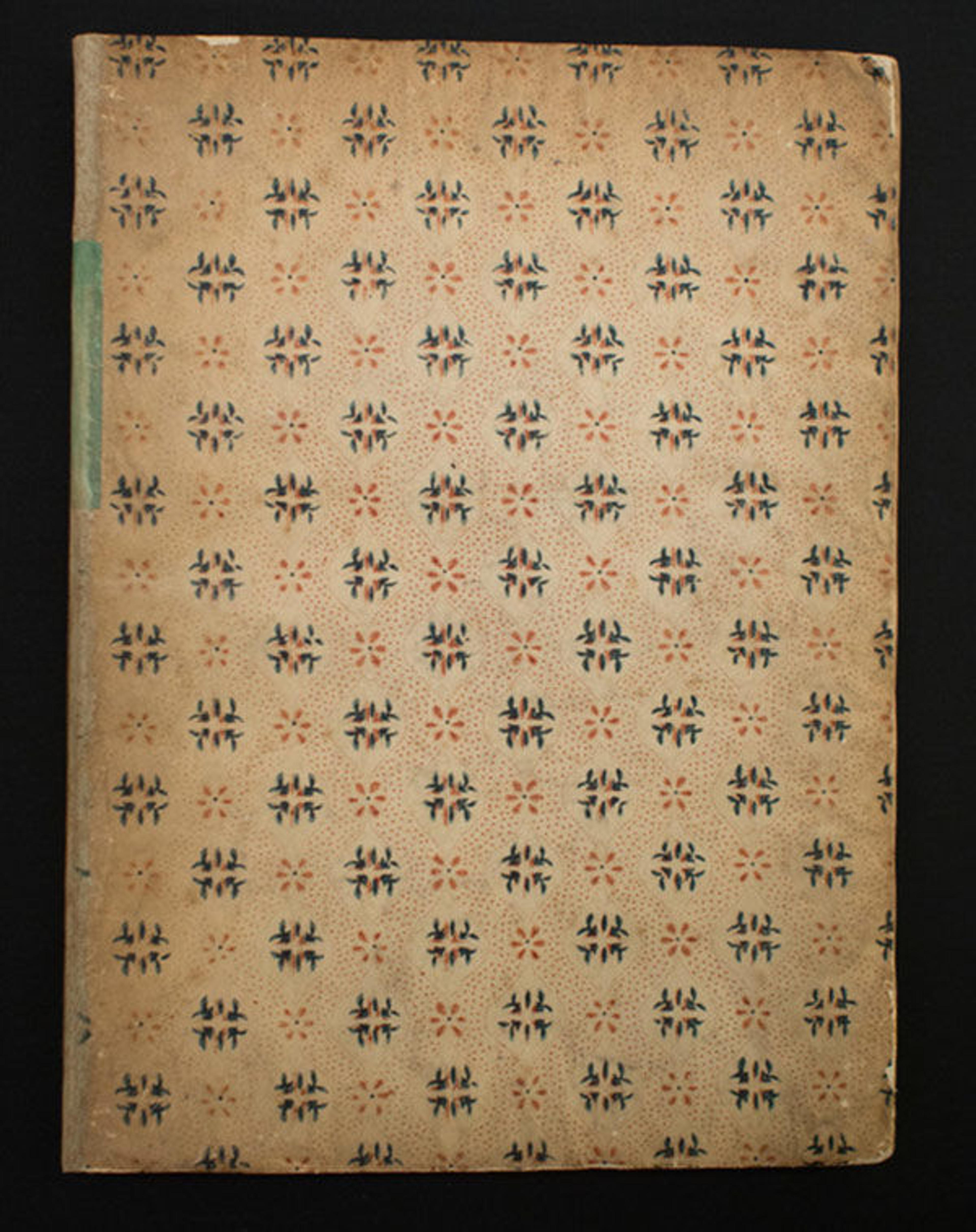

Block printed paper was available as early as 1550, but reached the height of its popularity during the eighteenth century. The process of creating this type of patterned paper was similar to that of cloth, and in fact eighteenth-century manuals describing the production of decorated paper encouraged craftsmen to use the same equipment on both cloth and paper. Eighteenth-century Italian papers were frequently printed with colored paste rather than ink.

The above early nineteenth-century Italian wedding book is bound in paper that features a pattern by the Remondinis, a family of Italian printers who were active for almost two hundred years. The Remondini family also printed reproductions of Old Master paintings, gilded damask paper, religious images, wallpaper, and they even produced marbled paper, though this represented a small fraction of their output.

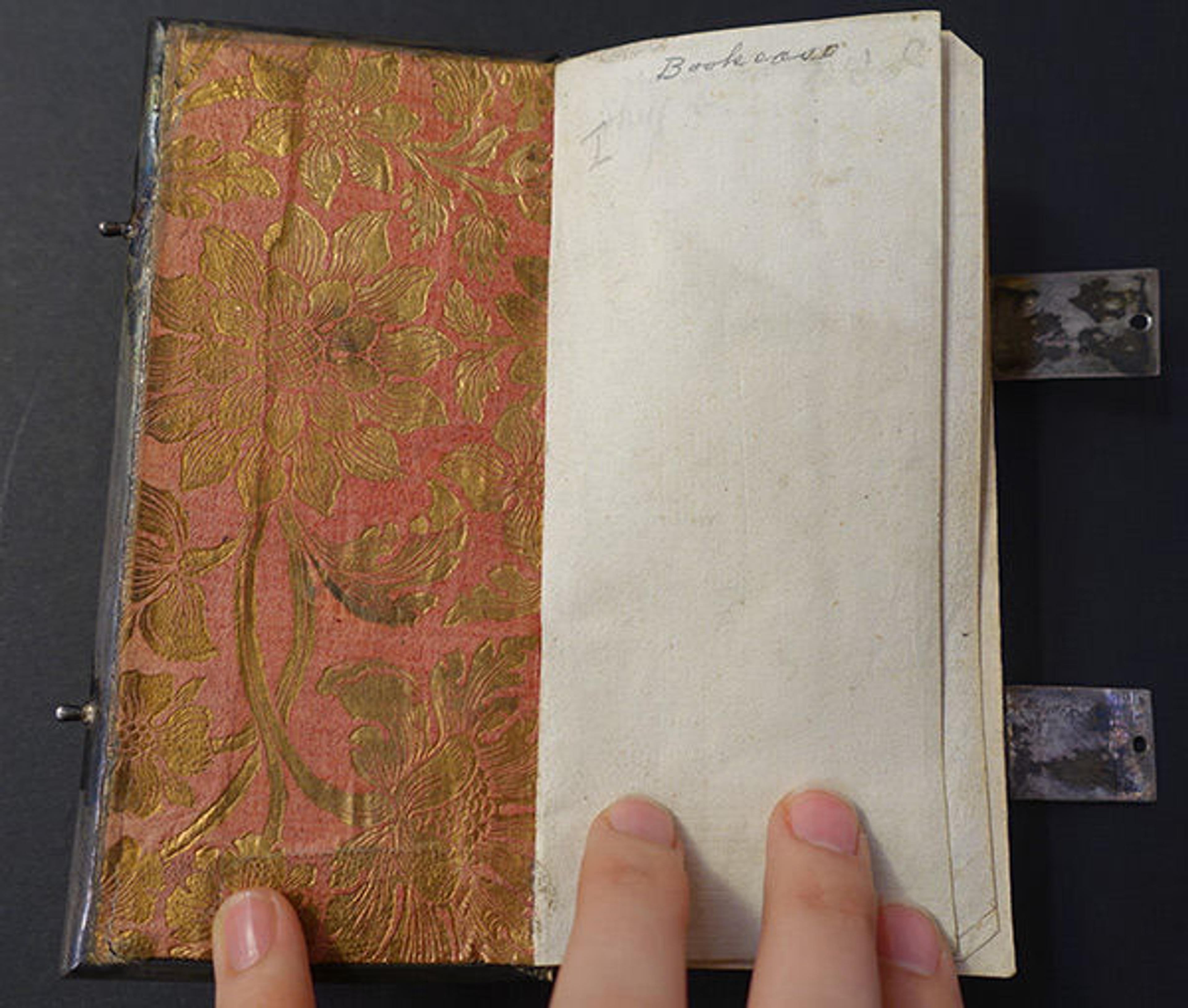

Arndt, Johann, Johann Arndts, Dess gottseeligen und hocherleuchteten lehrers Paradiess-gärtlein, welches voller christlichen tugend-gebete erfüllet. Deme zu ende beygefüget mehrere buss- und communion-gebete. Ulm: Druckts und verlegts Christian Ulrich Wagner, 1620

Dutch gilt paper was produced in Germany beginning around 1700 and continued until the early nineteenth century. These were produced with techniques already used for embossing leather, using engraved or cast stamps and an engraver's press. Due to their relatively low cost and highly decorative nature, these papers were quite popular throughout Europe, and their popularity spread quickly to the American colonies. Early British and American juveniles also made use of these bright gilded papers. In this silver-bound book with gilt edges shown above, the addition of Dutch gilt papers makes a beautiful complement to the intricate silver cover.

If you'd like to learn more about decorated papers, Marbled Paper: Its History, Techniques, and Patterns by Richard J. Wolfe, and Decorated Book Papers: Being An Account of Their Designs and Fashions by Rosamond B. Loring are great places to start. Both titles are available at Watson Library.